Some call it the accordion effect while others refer to it in terms of a bullwhip. Whatever the terminology, the supply chain mess has created a set of perverse incentives leading to a positive feedback loop: the greater the mess, the longer the times for delivery, the more product gets ordered if in only to increase the chance something, anything can make it past all those knots, stuffing even more goods into a now-bigger mess.

The anecdotes are starting to pile up to the other side of this. Whereas the mainstream continues to be flooded with stories about only inflationary impossibilities, how this supply disaster will last longer than “anyone” thinks, more and more there is the other possibility seeping into the close consciousness of those closest to the action (and frustrating inaction).

One example from just last week:

“Customers are just flinging crazy orders right now, so it’s hard to determine the real level of demand,” said the chief executive of Kids2, the Atlanta-based toy company best known as the maker of Baby Einstein and other baby-oriented brands. Business always surges around the holidays, but this year has been turned on its head by the pandemic.

A key danger in the current environment, he said, is that companies will order too many goods as they scramble to fill orders, especially in the run-up to the holidays, which could quickly lead to piles of unsold electronic baby books and high chairs once the crisis eases.

If demand does fall back even just to more “normal” levels, this weird inventory cycle transmutes into the more historical version.

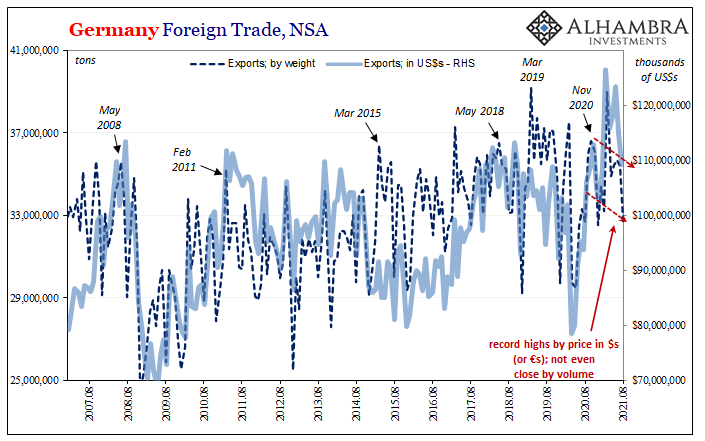

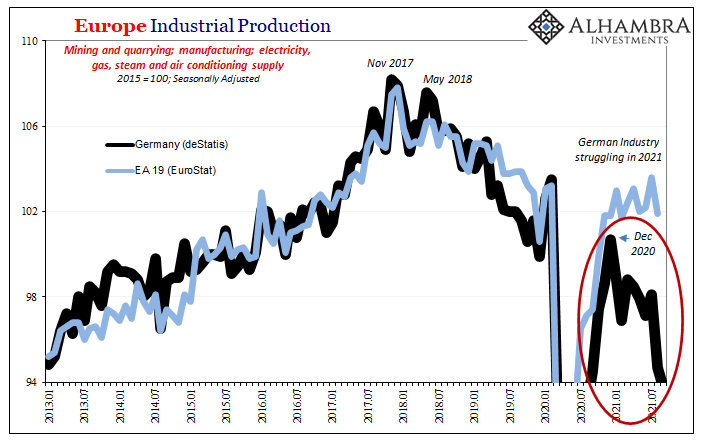

Signs of this have persisted all year despite the ubiquitous “inflation” story, a fairy tale careful to highlight especially West Coast port traffic to the exclusion of others. When looking instead at the big picture in 2021, this then is China or German manufacturing and trade which has been misleading by price compared to volume.

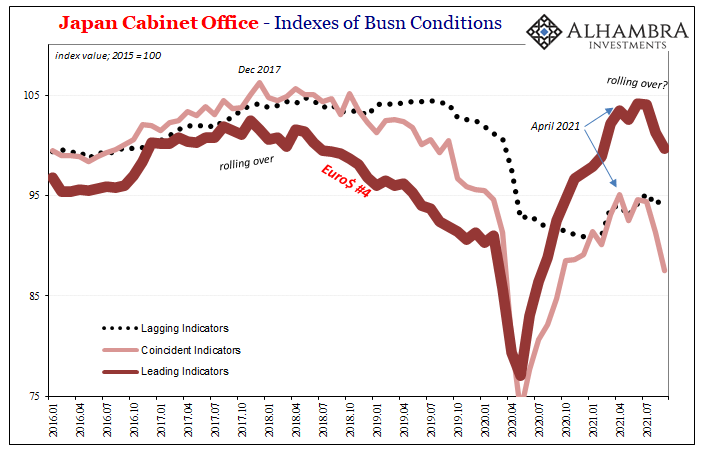

And we can’t leave out Japan, either.

It’s not just an issue of orders nor geography; a slowdown, or “growth scare”, begins in those places and only spreads from there. The growth, even the not-inflation “inflation” can swiftly disappear. In 2018, the year began with Japan and Germany nearly into recession which then became the situation near universally by the middle of 2019.

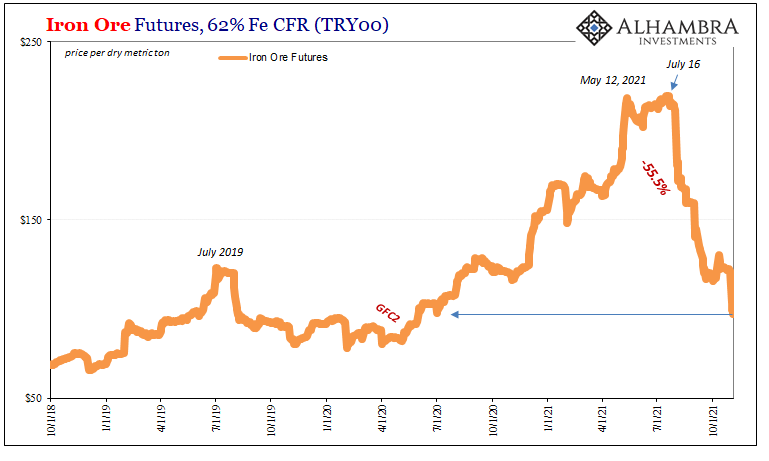

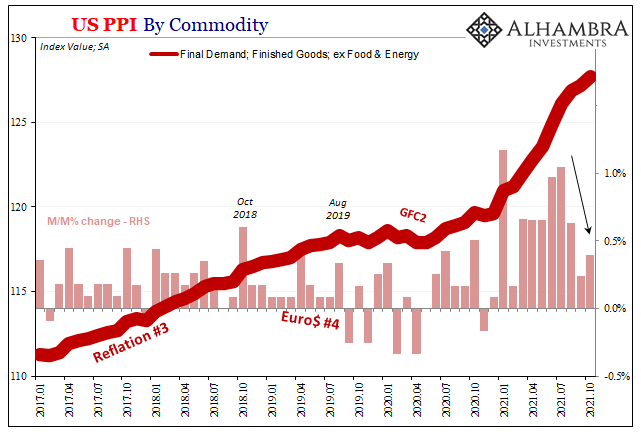

In terms of prices, that threat has already been the case from the standpoint of consumers (not just in the US) while at the producer level commodities and supply factors are and have been stickier. But even here for producers, what’s already emerging is a slowdown in price changes.

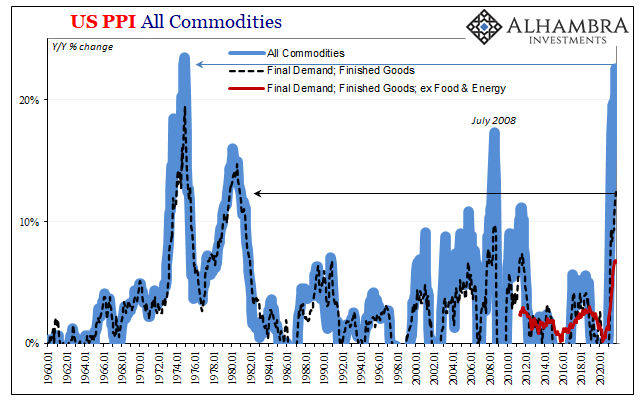

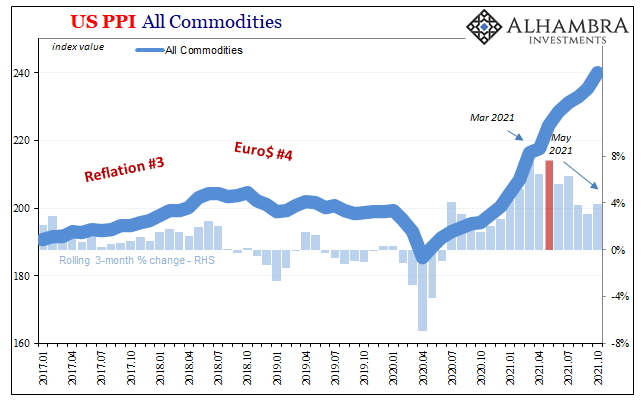

At the US PPI, the annual rates continue to be enlarged and will be for awhile; for general commodities, spiked by another rise in oil last month, approaching records year-over-year rates threatening to surpass even the OPEC embargo of 1973-74. Yet, even with these huge crude and energy contributions, and with the annual change at almost 23%, the index in more recent months is rising at an appreciably lower short-term rate.

It is still painful and unhelpful, just now starting to show itself as not inflation.

The further away from crude and other commodities impacted by their own set of supply factors, the far downward side of the transitory camel hump is much further developed. In the core PPI, the latest annual rate actually decelerated for the first time this year due to slowing price gains over the past three months; up 6.68% in October 2021 compared to 6.80% for September.

The downside of transitory price changes by itself means nothing more than those short run factors shaking loose and being overcome; the supply problems being worked out and more goods flowing more consistently. This is really all the price data shows so far, the emergence of some semblance of, and growing possibility for, normal.

But where it gets tricky is what comes after. Beyond any normal, the emerging threat is more than the supply side finding a less troubling equilibrium, it’s now total demand. There is still more goods coming, a lot more left yet to be delivered – therefore the above toymaker’s expression to major downside risk.

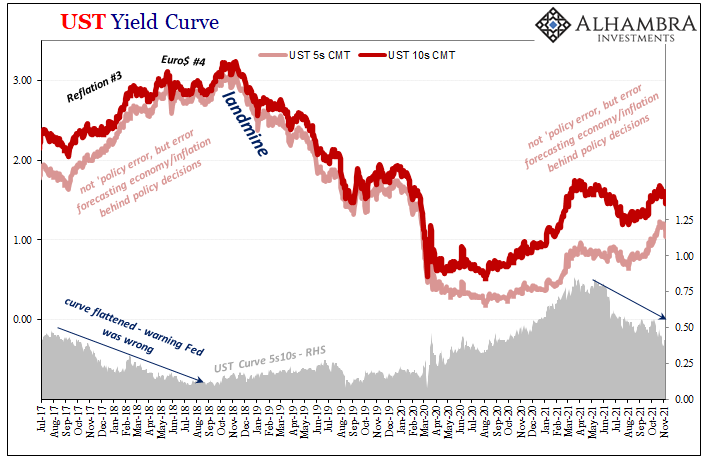

This is where the bond market comes into it. While the mainstream opinion remains solidly inflationary attached to supply-problems-are-forever, these other possibilities are actually the majority, increasingly the vast majority perception (of economic participants sporting an enviable track record).

The potential for a landmine and its role in all this is deciding which downside case will become more and most likely; before a bond market landmine, more of a chance this works out to be nothing more than that downshift in demand combined with better supply leading to less satisfying economic conditions but nothing too terribly awful.

Post-landmine, if it should get that far, is the other; where demand doesn’t just gently nudge into a modestly lesser groove, instead it becomes a self-reinforcing problem amplifying the historical kind of inventory cycle at the worst possible time.

More like the 2018-19 case. This is what makes the next few months/weeks crucial in trading.

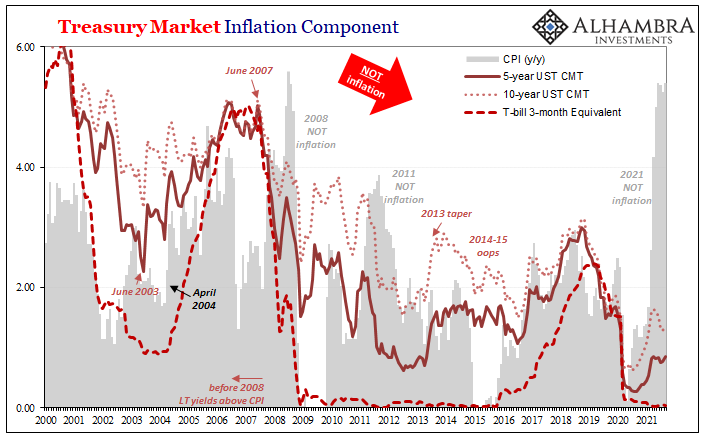

As always, too, either QE or tapering QE, neither factor into anything legit. Interest rates are about growth and opportunity. The yield curve flattening has basically eliminated inflation, actual inflation, from the set of realistic possibilities. It’s now about just how low for growth, and how supply and inventory might conspire against future opportunity.

Or not.

Stay In Touch