Irving Fisher was a prolific economic writer and thinker. In addition to decomposing bond yields into growth and inflation expectations, he also came up with something called the money illusion. He ever went so far as to write a book on the idea, published in 1928, for all his imagination called simply The Money Illusion.

At issue is, essentially, human nature. People think about their own situation in terms of nominal money, rather than in real values which are more complicated to figure out.

The way this is commonly explained is in the nature of wages and wage acceptance: most people would far more likely be satisfied with a 5% pay increase even if inflation is running at a 7% rate than they might in a situation where they wouldn’t receive any raise at all but prices are falling maybe 1%, or even stable.

In the first situation, overly simplified, the worker is actually 2% behind where they were at the start. The other situation leaves the same worker 1% ahead or at least in the same position.

Humans being humans, however, we’d rather see a bigger number printed on our weekly, biweekly, whatever paycheck. Only later do we complain, throwing our fists toward the sky in search of who in some official capacity or living down the street we might threaten to use them on given the palpable feeling of being left behind – if not knowing why or exactly how.

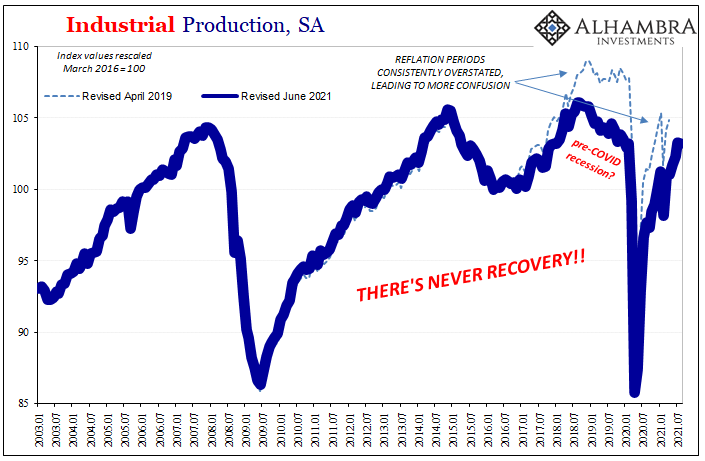

There is something similar which takes place in evaluating the overall economic situation, too, a money illusion as to the gross or aggregate economic situation. I’m not talking about GDP, which those who calculate the measure do an adequate enough job trying to balance nominal vs. real and present the difference as best as anyone might.

In specific economic situations or statistics where this isn’t available or possible, it can lead to serious confusion causing equally serious misinterpretations. I’ll give you a specific example building upon data I went through a few days ago.

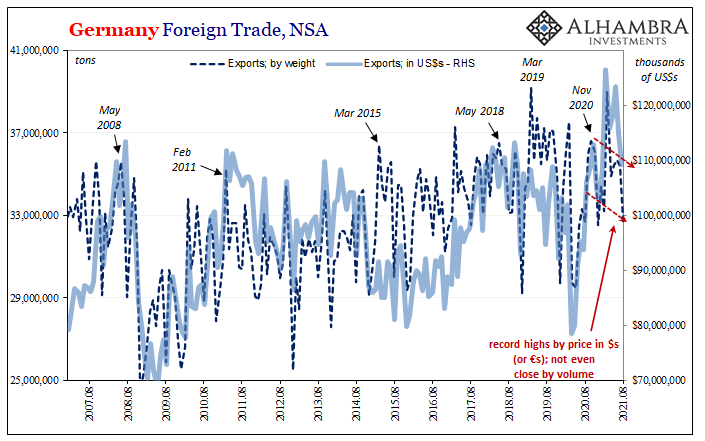

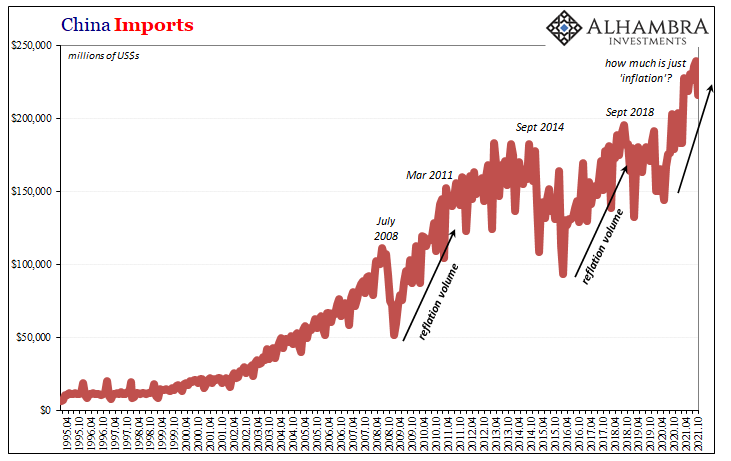

Trade values versus trade volume, specifically China.

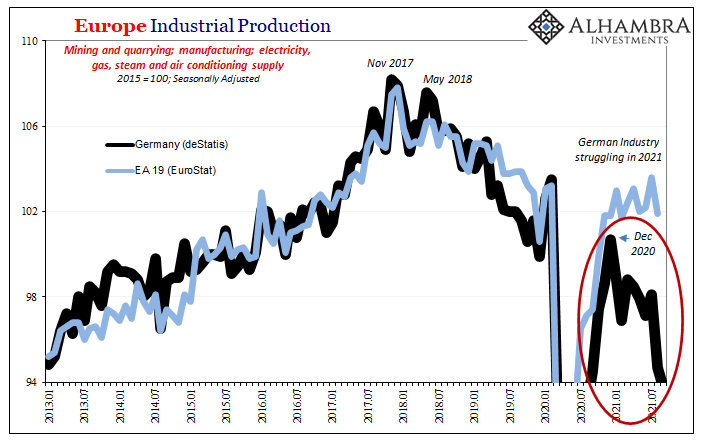

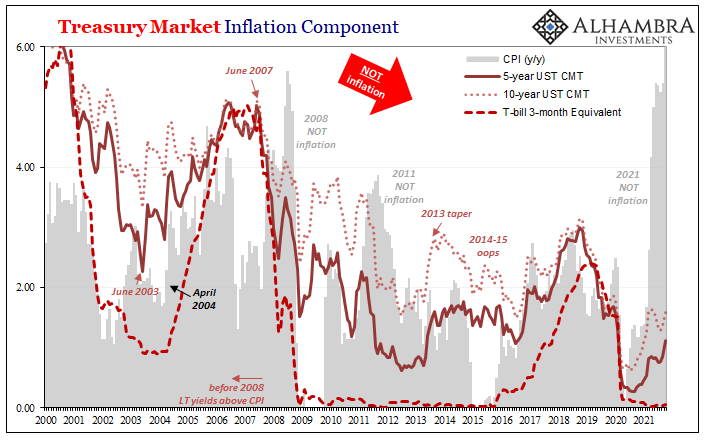

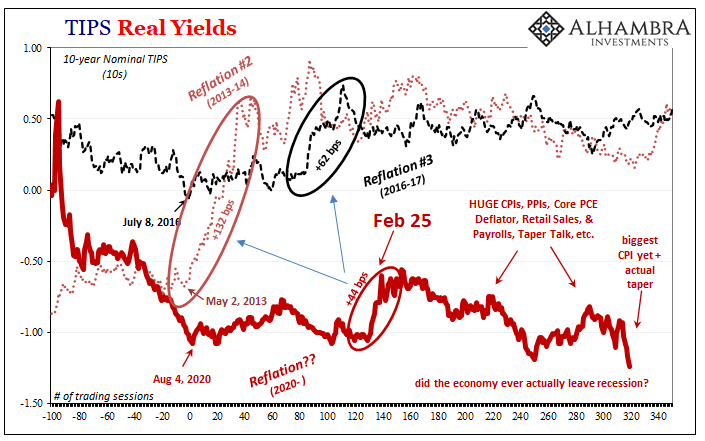

Put together, the “inflation” caused by the world’s shipping problems has created a confusing situation where it might initially appear as if a booming economy is plagued, being held back by nothing more than these supply shortages. Clear up the supply problems and, voila, full recovery is unleashed which would, in this view, make already “inflationary” conditions that much more inflation-y…

However, if we consider these prices as anomalous, and that the global trade system isn’t nearly so recover-ish, then what we have instead is a false signal (because no one seems to understand and appreciate inflation versus “inflation”) overlayed on top of a weak rebound which is being essentially eroded as this “growth scare” further develops.

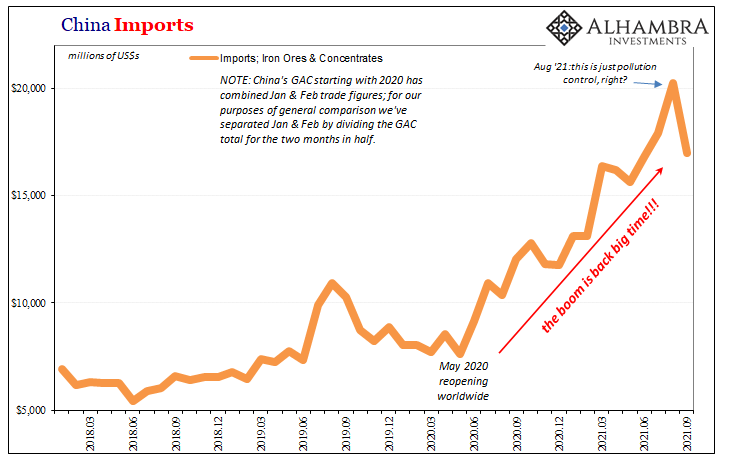

Using an even more specific part of Chinese imports – iron ore – we can piece together this very interpretation from specifically China’s activity in global trade of this one commodity (and therefore what it might portend for not just iron).

First up, the money illusion:

By dollar value of Chinese imports of iron ores and similar, it sure looks like China is back to its old ways of building the hell out of everything everywhere inside the country. Their economy must be so incredibly awesome that they can’t possibly get enough iron to keep the steel mills running – and that only government politics like pollution controls can be anything of danger to this robust, gangbusters recovery.

For the world economy’s savior, unquestionable demand whatever supply difficulties.

Right?

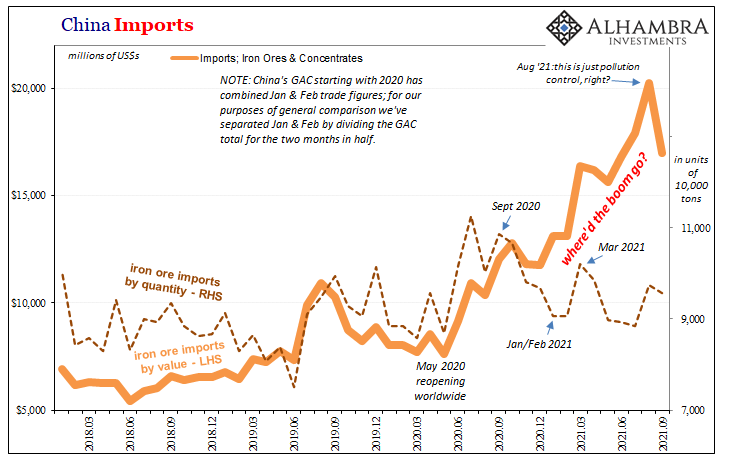

Digging into the situation, however, a very, very different picture emerges. As I wrote about China’s imports as a whole, the volume of iron ore imported shows us not just the illusion, more so just how big and therefore pervasive it must be.

The actual flow of material did rebound in 2020, but has been falling ever since the middle of last year (consistent with the general slowdown all of 2021 so far in all of China’s economic accounts, nominal or not). Of the past two months (up to September 2021) with iron futures prices dropping through the floor during them, total Chinese imports in tonnage weren’t any higher than they had been during 2018’s very real, very painful downturn.

Obviously, Chinese imports do not and cannot explain the entire more complex situation in the iron market as well as the overall global economy. But this is hardly an isolated instance where, on the one nominal hand, it only appears to be, given price behavior, the economy is, as Warren Buffett said, red hot.

The money illusion in this context sure might make it seem that way. Volumes – up and down the global economy – too often point to a vastly different macro picture.

Instead, what’s happened is supply and non-economic shipment factors have created the mirage of a recovery from what by volume or quantity is actually even more lackluster in total global trade and production than what I’ve presented here of Chinese imported iron ore.

This has serious implications, especially in how we might consider, in the US, something like the labor market situation. By nominal prices, given recent CPI’s and such, the economy really might appear to be on fire – when in reality it might be nothing of the sort.

What might this mean for the labor market as a whole which everyone says is held back only by the LABOR SHORTAGE!!!! Thinking the nominal economy is representative of the real situation, a shortage of workers might make some sense.

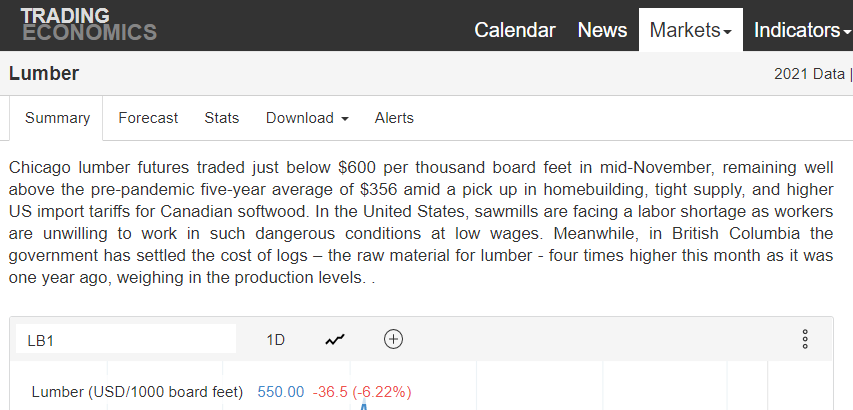

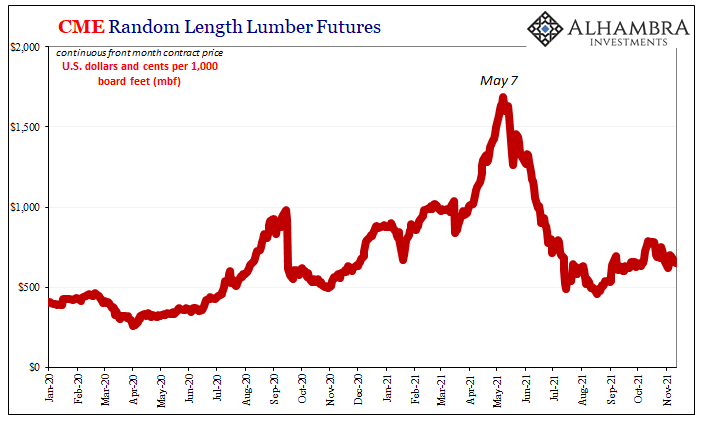

Coming at it, however, in this other way, you end up with a very different sense though one shot full with common sense. From the view of another former commodity darling, lumber, some inadvertent truth gets let out despite its previously epic rise:

In the United States, sawmills are facing a labor shortage as workers are unwilling to work in such dangerous conditions at low wages.

This is not a labor shortage by any rational thinking. It is, on the other hand, a clear example of a recovery shortage even when, for a while, prices made the situation seem otherwise.

If lumber “economy”, so to speak, is and had been as robust as the price of the commodity had put it, then sawmills would be beyond willing to pay the market clearing wage ending the “labor shortage” in a single swift stroke of uniformly higher pay.

The entire global economy this year has instead been injected with a non-economic pricing structure which has left most people – especially Economists – with the impression of some red hot, inflationary hot, awesome recovery.

Therefore, there really would be a labor shortage.

However, if the overall situation worldwide is more like iron and China, lumber and workers who won’t set foot in the mills without more nominal money, then for all the additional dollars (or currency) changing hands, they have done so for far less quantities (outright or in perception) being produced and moved than it might otherwise seem, therefore maybe not needing nearly as much rehiring and work as humanity has so far been led to believe.

The economy illusion. And that’s even before we even get to the statistical problems.

Stay In Touch