It began all the way back during the summer. Vice President Kamala Harris was in Singapore in August hosting a gathering of business leaders. Supply issues naturally came up, and the VP warned:

The stories that we are now hearing about the caution that if you want to have Christmas toys for your children it might be the time to start buying them because the delay may be many, many months.

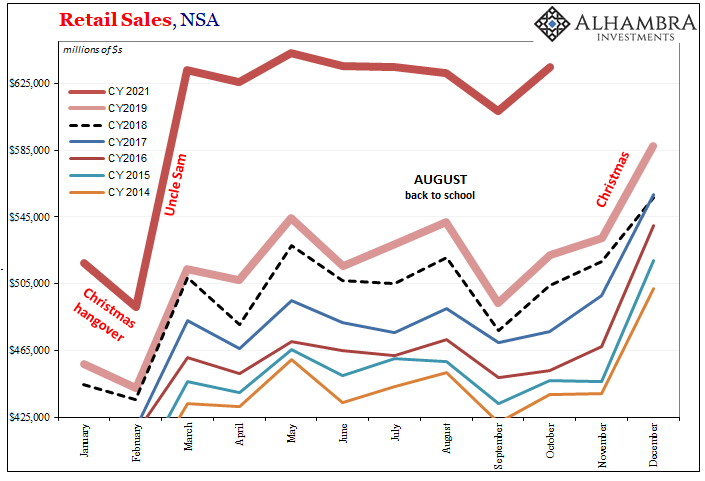

Naturally, consumers might respond to the world economy’s logistical nightmare by pulling forward demand, as Economists would say. Rather than wait for Black Friday to kick off the traditional (as in, before around 2017) holiday fever, this year it just may be Cyber Monday as the day when it all ends.

Early signs have all pointed to October, only beginning with re-accelerating “inflation” of the CPI. US demand (the rest of the world is a whole other story) seems to have been incredibly high for some reason:

This holiday season “continues the early shopping trend, with the added layer of inventory concerns motivating many shoppers to grab what they want when they see it, instead of waiting for better deals later in the season,” said Marshal Cohen, chief retail industry advisor for NPD, in its annual outlook.

As one author and purported retail expert cautioned, “If you want to guarantee that you have your presents available for Hannukah or Christmas, then you must be done by Thanksgiving.”

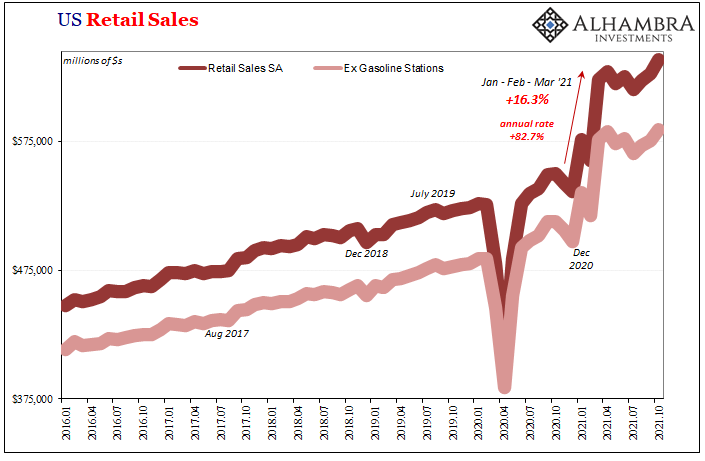

According to the Census Bureau and its retail sales report, this seems to have been the case already. Total sales were, somehow, “unexpectedly” strong besting the best best guesses of whichever analysts the media surveys. On a seasonally-adjusted basis, total retail sales surged by 1.7% from September to October. That’s a huge increase for any single month at any time.

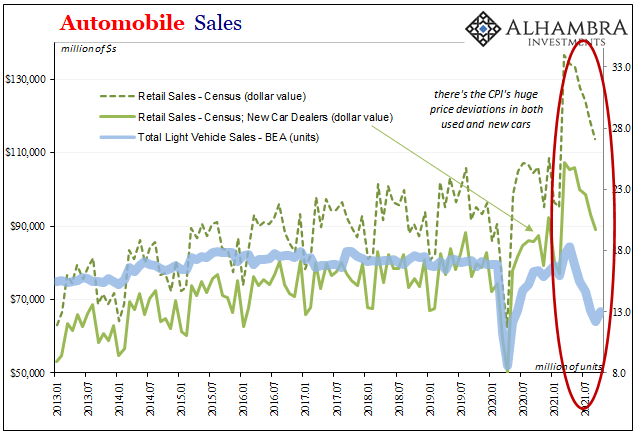

How much of it was early Christmas, and how much might have been attributable to higher average prices?

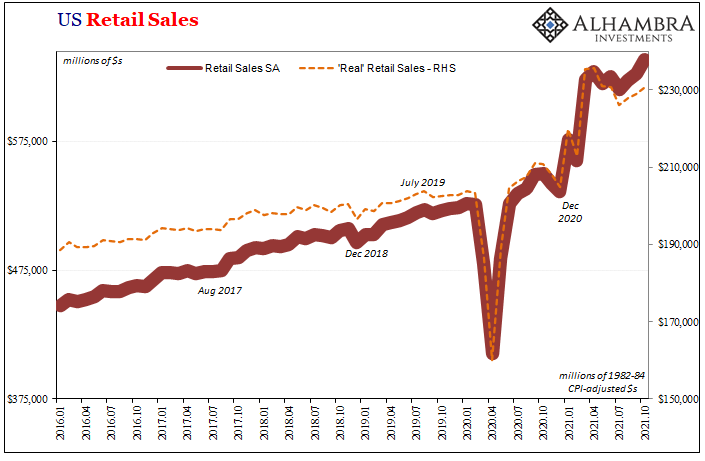

To find out, we start with the unadjusted retail sales to see if the pattern fits overall. Most years, there’s an increase of varying levels from September to October not accounting for any seasonality. It’s difficult to guess just what “normal” spending patterns might be applied to 2021’s massive spending, but so far it does look very seasonal. Next factoring prices, which Census quite handily provides a version of “real” retail sales that are deflated using the BLS’s CPI – including what’s been reported in that for October 2021. In nominal terms, retail sales had gained a 1.7% monthly increase; in real terms, “only” 0.7% month-over-month.

Next factoring prices, which Census quite handily provides a version of “real” retail sales that are deflated using the BLS’s CPI – including what’s been reported in that for October 2021. In nominal terms, retail sales had gained a 1.7% monthly increase; in real terms, “only” 0.7% month-over-month.

So, a substantial contribution via higher costs per purchase. And that in and of itself might have been a motivating factor (see: below). But how does a 0.7% October monthly gain compare in real terms? Not surprisingly, it’s well above almost every year’s October apart from a notable one.

Typically, the series (again, in real terms adjusted as best we can for prices) gives us relatively decent monthly increases to start of the holiday seasons, somewhere around 0.1% up to 0.3% increases each September to October during the “better” years (such as reflationary 2013 and 2014).

The year which stands out is obviously 2018, which raises several similar concerns to what we are looking at in 2021. As it would turn out, that big increase during October ended up being the last gasp of retail strength for the entire reflation cycle. By December, typically the month of months on the retail calendar, the entire holiday season would end up as a washout.

But why? I think a lot of it had to do with similar factors including the whole middle months of the year filled with inflation hysteria. Throughout the Summer of 2018, “everyone” said it was going to be a big issue, so much Jay Powell’s Fed had to get moving on rate hikes to cool off the blistering hot economy.

And by September and October, to the average American it probably did seem like this was possible maybe even likely. Remember oil and gasoline prices had risen sharply (though not nearly as much as 2021), so there was that incentive to shop early and often before prices changed for Christmas goods in the same way they seemed to be changing at the pump.

It’s not likely random coincidence that the motor fuel component of the CPI bucket reached its local top right in October 2018 (16% higher than in October 2017).

Then the wheels fell off: Euro$ #4’s landmine had hit the US and the whole economy suffered a bit more than an early Christmas hangover. Instead, 2019, a full downturn and, I believe, a recession by the end of that year or the start of 2020 (pre-COVID).

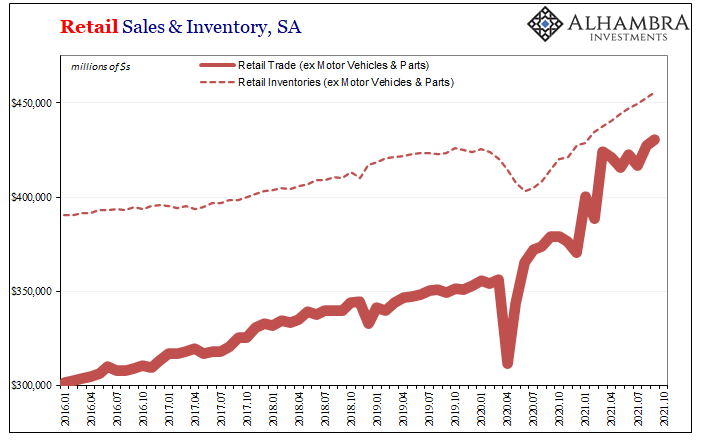

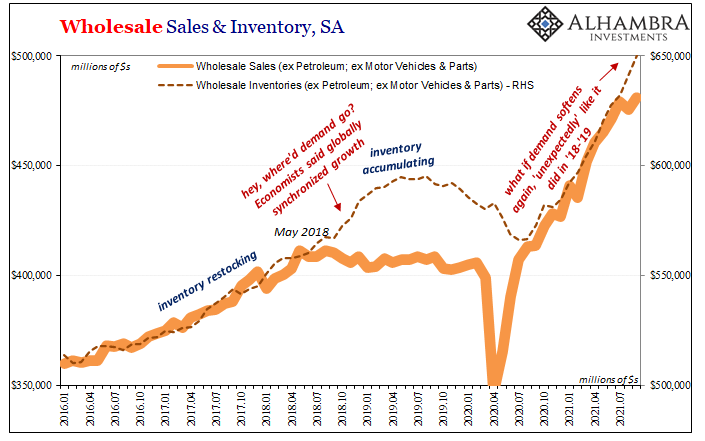

The prospect of repeating the 2018 pattern, the plethora of retail and political warnings, and on top of gasoline prices rising even more painfully this time around, consumers are being motivated by these supply warnings, too. Not only does it appear like the entire retail holiday season is being pulled forward, we also have to consider the other side of the retail equation in terms of inventory management.

“Customers are just flinging crazy orders right now, so it’s hard to determine the real level of demand,” said the chief executive of Kids2, the Atlanta-based toy company best known as the maker of Baby Einstein and other baby-oriented brands. Business always surges around the holidays, but this year has been turned on its head by the pandemic.

A key danger in the current environment, he said, is that companies will order too many goods as they scramble to fill orders, especially in the run-up to the holidays, which could quickly lead to piles of unsold electronic baby books and high chairs once the crisis eases.

Not just as the supply crisis eases, but also if the Christmas aftermath comes early and ends up being harsh – even if not quite late 2018/early 2019 harsh.

Retail sales have been outpacing inventory (taking account of the very different supply situation for the auto sector, where sales data continues to conflict) by a good amount, but this doesn’t mean inventory hasn’t been rising substantially itself. Inventory-to-sales ratios look good only so long as the consumer frenzy stays frenzied.

It’s a bit misleading, therefore, how overall goods prices reflect the high level of sales even as inventories are also extremely high just not as high – the same classic supply/demand imbalance. It may not look like much by comparison, but retail inventories are a sharp 7% above where they’d been in October 2019 rising at their own elevated pace.

Otherwise, there’s as much inventory for retailers, more (relatively speaking) stuck on wholesalers, and who knows what floating around on ships and how anything might be accounted for trucked or on rail.

As the man said, “it’s hard to determine the real level of demand” made all the more difficult as an early October Christmas season seems to have come even earlier, prices, price behavior and all.

Stay In Touch