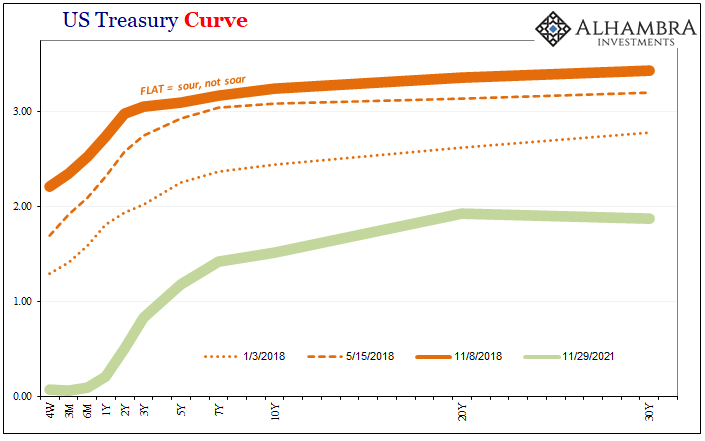

This sour/soar stuff goes back many years. The last time we went through the same hysteria (if for different reasons), everyone said the global economy was going to accelerate, take off, and sail onward forever after. The world was, they all claimed, set to soar.

Globally synchronized growth.

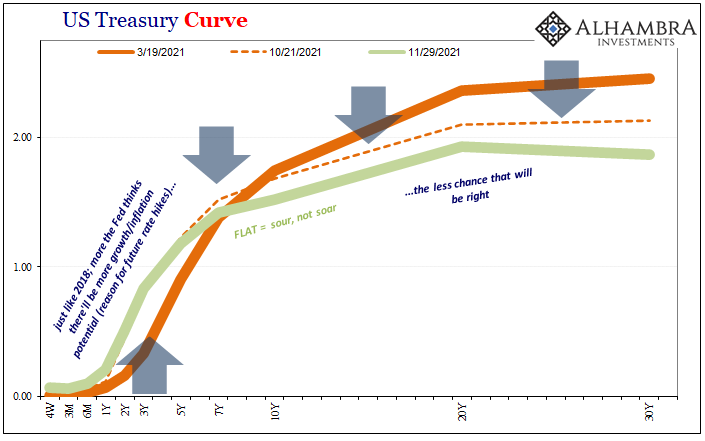

The bond market didn’t just disagree, it did so vehemently, a pessimism when 2018 began which only gained (and spread) as the year went further on. The more Jay Powell and those who followed him were certain of a soaring, inflationary economy, the more the market became increasingly adamant the global economy was far more likely to sour.

But what did that actually mean?

Flat curves were merely the vessel into which contained the message. That flatness was the market discounting balance of probabilities in whichever direction seemed most probable. And it did so correctly, as it turned out.

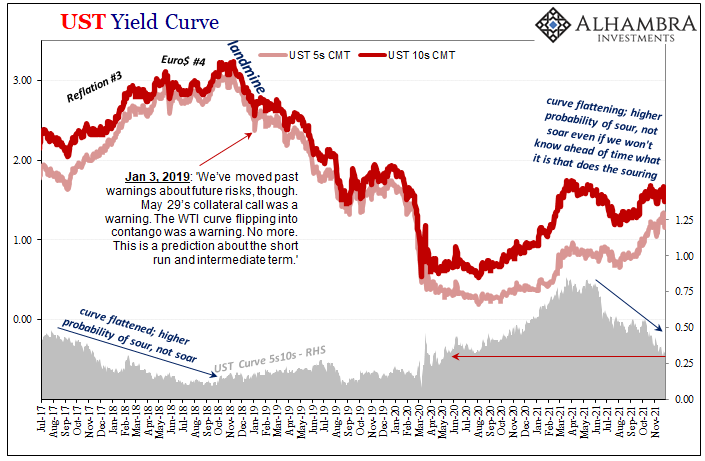

As I wrote in early January 2019, the world’s fate had been decided:

All this is the predictable outcome of the flat yield curve, especially around or now under 3% nominal. UST’s and eurodollar futures had been saying all along throughout the entire run of Reflation #3 that the chances the global economy was going to soar were nowhere near the chances it was going to sour. Curves are not just about inversion and recession; in fact, the curves are far more interesting outside of those contexts.

December was extraordinarily sour, with eurodollar banks getting to taste it first and spread it around.

The bond market is the banking system, and the banking system is the money put into, or pulled out of, the real economy in real-time. You should pay attention and not listen to those selling inflation who claim, without evidence, the Fed has rigged the very thing discrediting the inflation narrative.

In other words, maybe the market hadn’t known exactly why 2018 would sour rather than soar, given a combination of things to consider, participants simply judged the risks as too unbalanced unfavorably for the latter case to have been realistic at any point. Maybe it didn’t exactly matter just what ended up being one negative too many, since the situation was perhaps doomed from the start (Euro$ #3), susceptible enough to any negative development.

No one possessed a crystal ball with impeccable prediction capabilities. The situation, in reality, flat curves, the market judged the probability of something bad happening as additionally high, and, the more 2018 went on the wrong way, the higher probability whatever bad might develop it would lead to more certain negative general economic as well as specific financial outcomes.

You might have blamed trade wars, some fingered “rate hikes”, I happen to believe it was clear collateral concerns (especially after May 29).

By November and December, whatever just what happened it merely went from high sour probability/low soar probability, to sour certainty. Landmine.

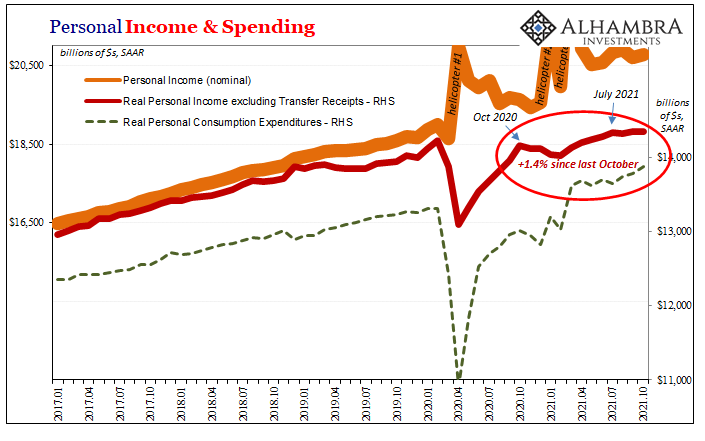

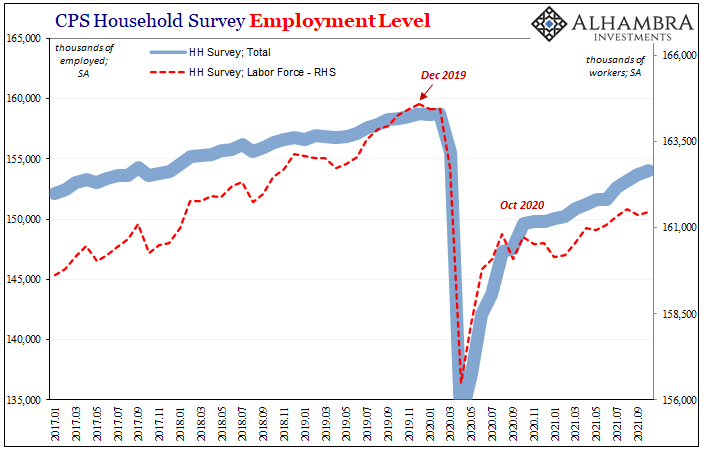

For a time late in 2020 and the first few months of 2021 (before Fedwire spoiled the party), soar seemed to be restarting its own following on the developments of vaccines along with Uncle Sam’s overabundant generosity (as well as other global forms of “stimulus”). For a time, the curves all moved in the favorable direction – if but a tiny bit (relatively speaking).

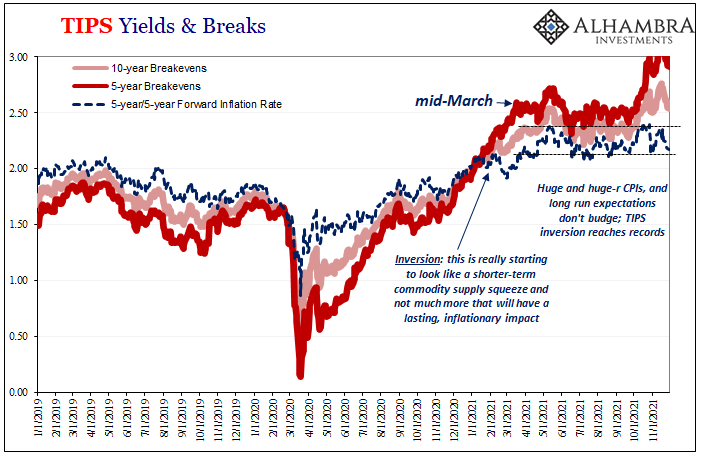

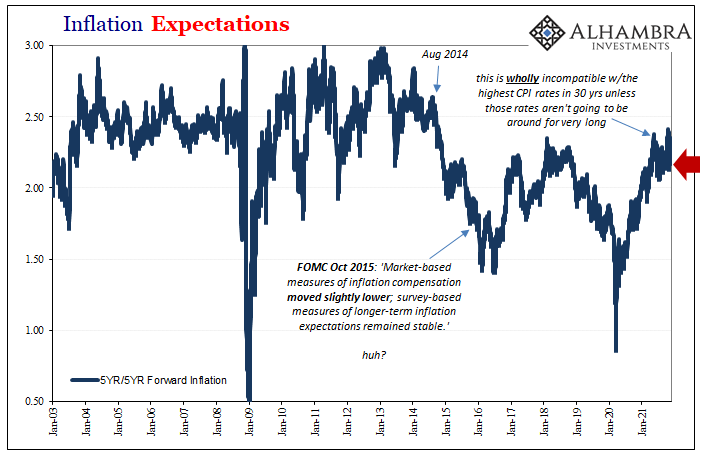

Since mid-March, however, the global “bond” market has been consistently moving back in the direction of sour all over again. Inflation dominates the mainstream media’s narrative, yet here it is increasingly dismissed as improbable. Just like 2018, it’s becoming more and more at opposite ends.

Why?

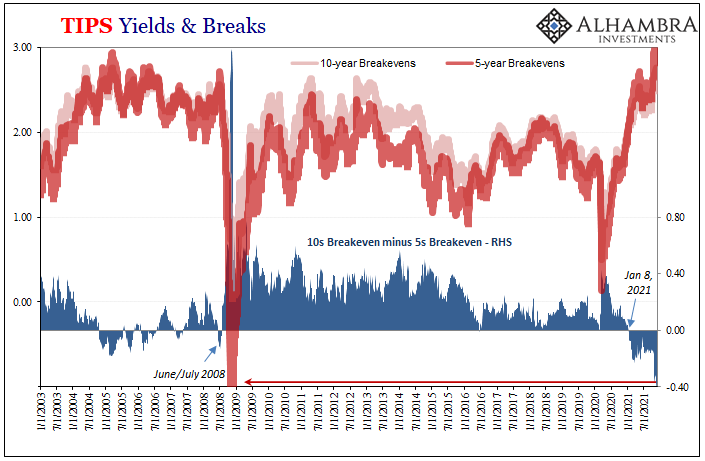

To begin with, flat curves, the market is once more positioned for balance of unfavorable probabilities. The specific case is again not knowable ahead of time, just that there are enough problems roiling below the surface right now that any one of them is more and more likely to spoil the rebound (and inflation; see: TIPS data below).

It could be collateral again (scarcity), or the inherently weak state of the recovery apart from all its artificiality. Maybe the predictable overreaction to the next wave of corona.

I don’t mean that the flat curve (and upside-down inflation expectations) in the Treasury market had anticipated delta and now (moronic) omicron, the curve – especially given Friday’s landmine-like behavior – has been pricing an increasingly hostile situation increasingly susceptible to almost any negative development of any kind.

Thus, the flattening, low yields of last week were more confirmation of these very real, very high negative potentials.

Given the reality of the global situation since April and May, “growth scare”, would it really take much for the current situation to more thoroughly unwind in such negative (deflationary; see: oil) fashion? Even if the latest COVID strain turns out to be nothing, like trade wars, the market has already priced the imbalance of outcomes regardless of eventual spark or cause.

If not omicron, then whatever the next thing might be (not necessarily pandemic-related) – because markets are pricing a near-certainty of whatever next thing.

It isn’t sour certainty as December 2021 approaches, not just yet. Maybe since March collateral scarcity and the thoroughly disappointing economic rebound have already set the world on edge. That’s the thing about sour; in truth, as we saw in 2018, it might not take much to tip the thing over.

That’s the flatness, and the probability distribution behind it even if looking ahead we don’t know what might be the final straw. The market wasn’t predicting omicron (nor delta) all the way back eight months ago, it was betting on the high and higher likelihood of something, whatever it might be, coming along and more easily turning an already bad (not inflationary) situation into that sour certainty.

Stay In Touch