I’m not saying it is the whole story, but it’s not just random coincidence, either. It can’t be. At each inflection point when the global eurodollar system rolls over from reflation to the next major funding squeeze, you will find the debt ceiling nonsense rolled on into that process.

Every time.

On September 8, 2017, the debt ceiling was temporarily suspended by Congress and it remained an ongoing issue well into 2018.

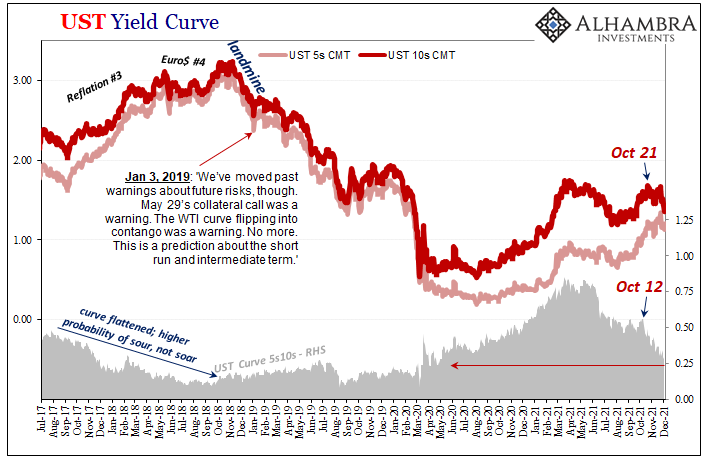

By “chance”, from September 2017 (the 5th, specifically) forward, Reflation #3 (globally synchronized growth) turned into the beginning of what would end up being a powerfully bad Euro$ #4.

On May 20, 2013, then-Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew notified Congress that he had declared a “debt issuance suspension period” (DISP) right from the start of the so-called taper tantrum (which wasn’t a tantrum but a brief celebration). By August 2, Secretary Lew would extend the DISP through to October 11.

Pure coincidence, then, how Reflation #2 started to break down especially around September 2013 when eurodollar futures abruptly ended their “celebration” and began to ominously price/predict Euro$ #3 which arrived in full by the end of that same year?

Before those, in June 2011 the FOMC was keeping its confused eyes on, yes, the Congressional funny business tied also to the debt ceiling. At the policy meeting held during that special (for all the wrong reasons) month, Open Market Desk Manager Brian Sack relayed the substance of the issue without appreciating the full range of its implications:

MR. SACK. Some market observers are concerned that the looming debt ceiling is going to impose a substantial squeeze in the supply of Treasury bills, as the Treasury attempts to maintain its coupon issuance while its ability to borrow is limited.

This, yet again, right smack in the middle of reflation (#1b) transitioning into another very bad global monetary squeeze (Euro$ #2).

As I started here, I’m not saying that the uncertainty this needless debt ceiling theater produces is the proximate or primary reason why reflation dies and becomes the next eurodollar event. However, the repeated coincidence at least suggests some manner of relationship.

For one, a fragile system abhors such uncertainty particularly if that ambiguity features unwelcome volatility, and even more so where unwelcome volatility might strike the one part of the system which is supposed to be reliably free from any.

T-bills.

The whole thing with bills, why they are the best of the best of the best, is that they are price-insensitive. If the Fed’s going to raise or lower rates, who cares? Outside massive deflation (which is hugely price positive) like 2007, 2008, and 2020, a 3-month bill isn’t going to make anything but predictable patterns. The shorter the bill’s maturity, the less you are ever going to worry about changes in its price for just about any reason.

Except the debt ceiling.

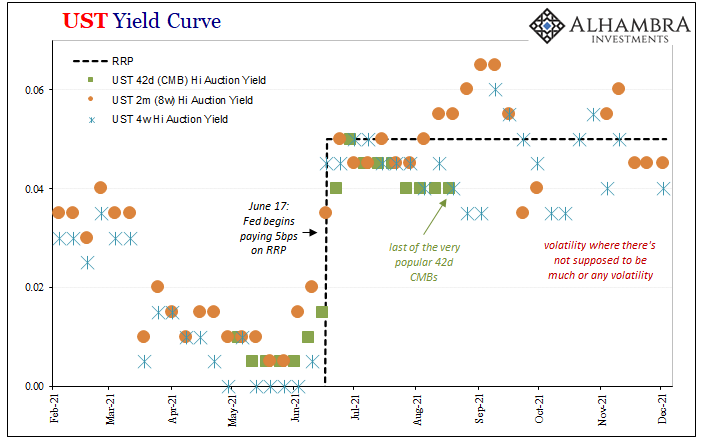

The second half of 2021 has seen this stupidity come around for another time. And just as predictably, the bill market has become an utter unpredictable mess, so much so you can actually and easily observe when it shifted (therefore why):

When bill yields were falling earlier in the year, even though that was rising collateral scarcity there was still the obvious hierarchy volatility-free. But once Treasury began to adjust for the upcoming deadline, around late July (which sounds familiar) the whole thing has been stricken by unnecessary disorder.

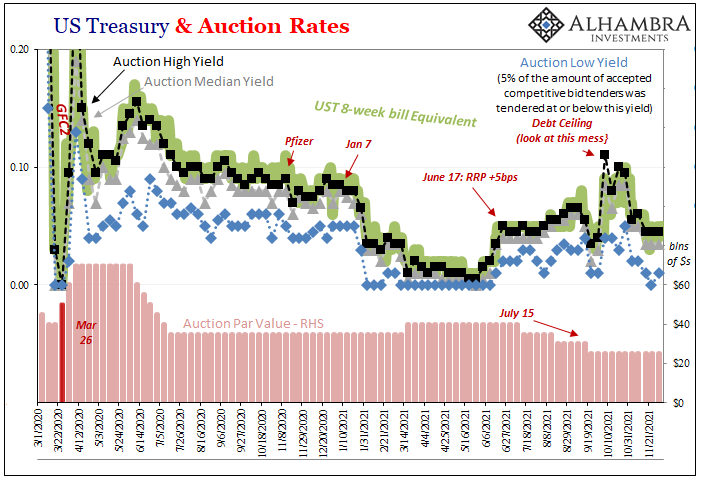

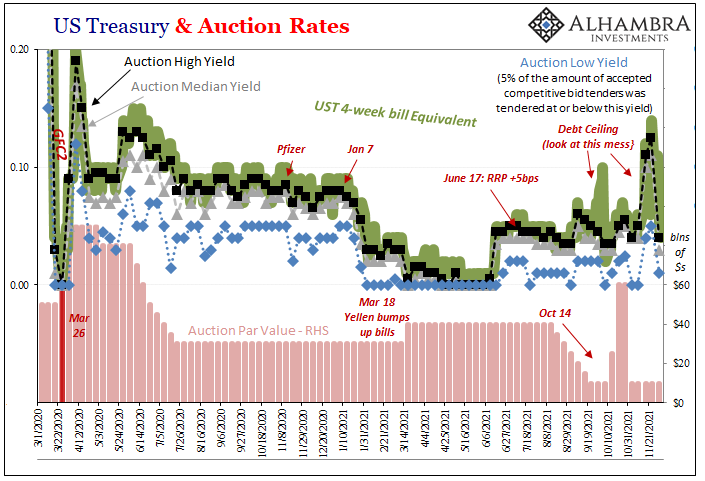

Take, for example, the 4-week bill – the most dependable and most money-like substitute. To start with, prices now range all over the place; both secondary as well as primary markets. In just the last two auctions, last week’s on December 2 and the week before on November 24, completely chaotic.

The high yield on the 24th was 12.5 bps with a median of five. One week later, the high yield paid was just four bps (a full one below RRP) with a median of only three (two below RRP). The only thing changed from one to the next was the arbitrary December 2021 limit.

Politics.

But it wasn’t just price behavior afflicting the 4-week maturity (and others). Look at the wild swings in gross issuance:

From $10 billion the week of October 7 to $25 billion the next week then $60 billion for two weeks thereafter. Back to just $10 billion again early November, when issuance had been $40 billion previously.

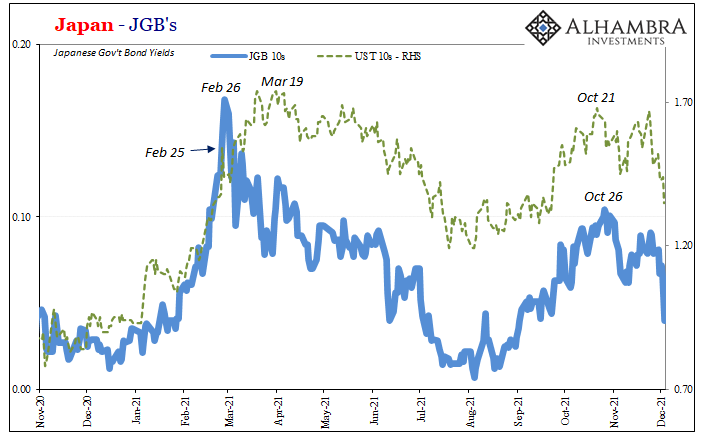

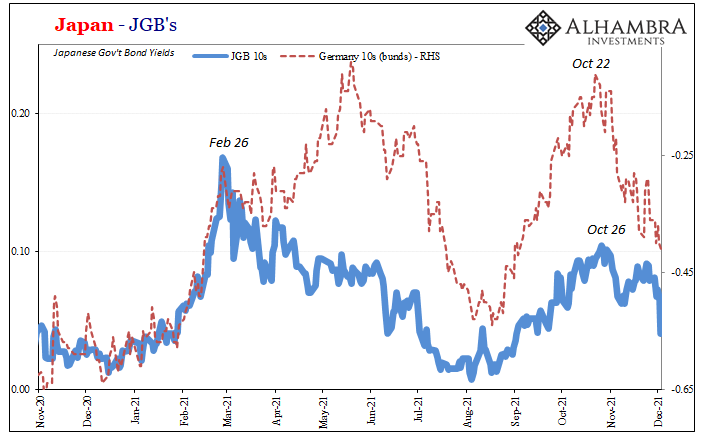

Perhaps, too, no coincidence that the latest bout of increasingly serious deflationary pressures has been priced into global markets since around late October.

Why would this be such a big problem?

Simply because these instruments in the front end of the yield curve are supposed to be an oasis of calm even amidst the most uncertain of times. Interest rate risk can creep way up the yield curve especially during periods of reflation and “hawkishness”, it isn’t a problem for the shorter bills.

But if there are other factors like this that do spoil the quiet, then what’s left for the whole collateral system beside uncertainty therefore at least some substantial level of risk aversion?

As we know only too well, there are two seriously negative and deflationary issues when it comes to collateral – each side of the collateral multiplier. Either supply of bills, or the amount of times they (and notes or bonds) get re-used, re-pledged, and, yes, rehypothecated.

Risk aversion typically means not as much re-using, re-pledging, or rehypothecation because these collateral chains become less reliable, predictable, and resilient when the best of the best collateral swings around wildly for no useful reason. The collateral multiplier must shrink.

Since this outcome comes out when the debt ceiling is on the table, as you can see above, that also means the supply side of the multiplier is an uncertain question, too.

Deflationary on both sides can’t be good; it certainly won’t lend anything to purported inflation expectations.

While I don’t believe the debt ceiling and its related bill volatility is the specific reason why reflation dies and the next global dollar shortage develops, it absolutely does not help, and, most likely, the collateral pressures instead push the system further in the direction of monetary shortage and deflation it is already taking.

And if it is, this would be just another indication of how fragile the system actually has been (forget “too much money”). What in a healthy world of sufficient monetary resources and redistribution (and intermediation) would end up as nothing more than a curious historical footnote (why no one outside of political junkies had ever been bothered much about prior debt ceiling episodes).

Euro$ curve inversion and now two China RRR’s, and a dramatically flatter curve(s) since mid to late October (so much for the CMB deluge). Something appears to have accelerated the downside risks which are, for now, evidently sizable if still risks.

It hasn’t been omicron.

Stay In Touch