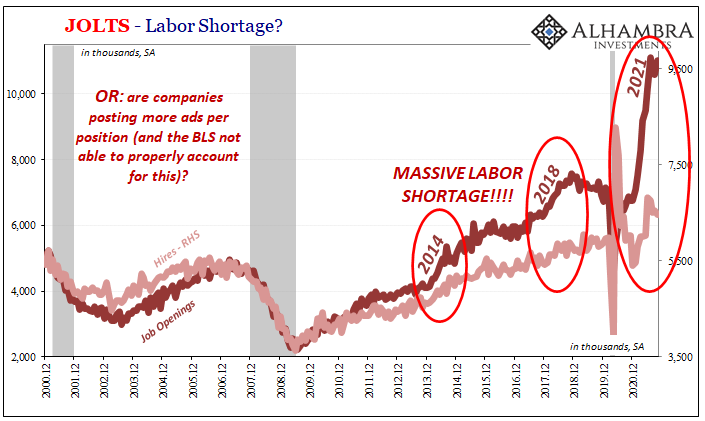

The Bureau Labor Statistics reported today another huge month for Job Openings (JO). According to their methodology (which I still believe is flawed, but that’s not our focus this time), the level for October 2021 (JOLTS updates are for one month further back than payrolls) was a blistering 11.03 million.

It wasn’t a record high, though, as that was set back in July. Yes, the number remains upward in the stratosphere, but it has been in the same general area of it since June. Spoiler alert: this will be a persisting theme.

Possibly a plateau – an incredibly far up one – which, for four months, means perhaps something important. Maybe JO had nowhere further up to go, and this was as high as it could ever have gotten. Or, possibly, there’s been a change in intensity.

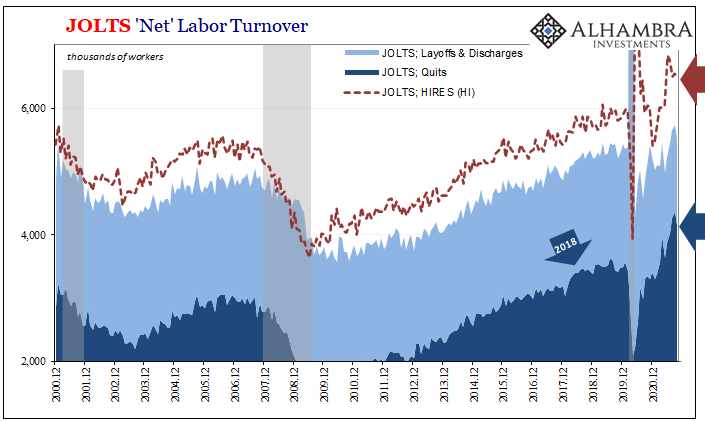

For one, American businesses refuse to hire (JOLTS HI) more workers. Labor shortage, they say, yet the other labor statistics from the CPS (Household Survey) bely that notion with so many millions in slack leftover from 2020’s labor market destruction piled on top of more millions who still haven’t been able to work their way back to work going all the way back to that GFC thing-y in October 2008.

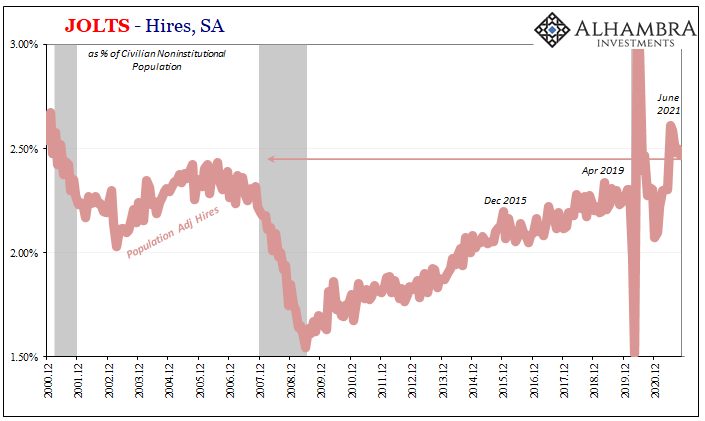

The rate of HI was thought to be 6.46 million two months ago, yet that wouldn’t have been anything special had it occurred in the lackluster middle 2000’s (chart immediately above). For an economy supposedly on a tear, and with purported demand for workers way, way above historic highs, it’s more than curious the lack of similar proportions for hiring given what we’re led to believe is the historic need for it.

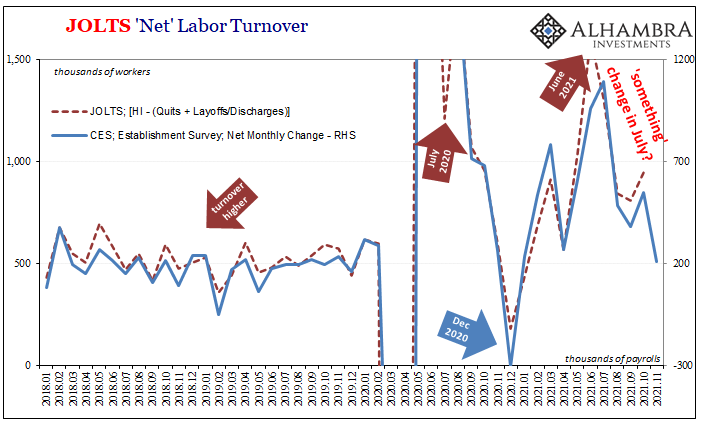

For our immediate purposes here, however, like JO we find that HI (raw number like population adjusted) had peaked, when? That same month of June 2021. There had been a clear reopening frenzy, the final one perhaps, but then July forward it hasn’t been awful by any means, but more and more divergent from an already flattening out JO.

Instead, as you would expect since JOLTS is benchmarked to CES estimates, the labor market seems questionable and at least slower once the seasons shifted – coinciding, of course, with the increased frequency of “disappointing” monthly payrolls counting the last one for November (one month beyond these JOLTS).

Even the epic rate of quitting (JOLTS QI) cooled off at least for October. Net turnover largely matched the Establishment Survey’s net gains, mostly because of the missing positive momentum which should be propelling hiring activity – unless something else really is going on here.

It’s not a labor market crash, yet there needn’t be one to lead toward “growth scare.” On the contrary, the employment situation in reality should’ve been bullet-proof, uninterruptable given that recovery in theory was still in the works. To put it bluntly, given just how far real recovery would still have to go, there shouldn’t be any slowdown of any kind to any degree let alone one that is consistent across not just JOLTS nor only US labor data.

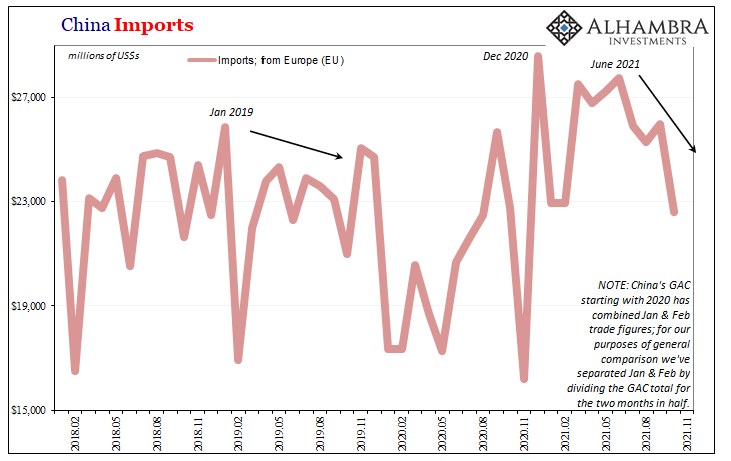

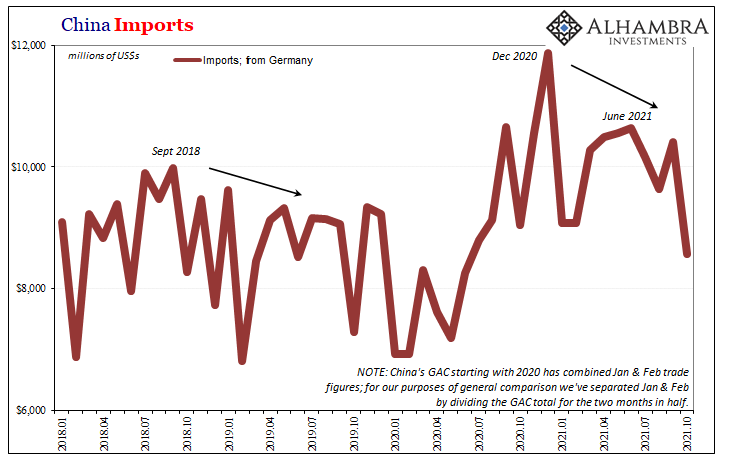

Time and time again, June and July show up as a potential turning point in economic data in the same way April and May had for market prices and indications. Something clearly happened which, moving toward and into Q4 2021, changed the economic trajectory from one which was already suspect to another even more (dangerously) so.

What was it that could have spoiled the trend?

To start with, Uncle Sam; helicopter payments and other transfers were heavily front-loaded into the first few months of 2021. Ever since, they’ve been fading and falling out, leaving the underlying real state of the private economy more exposed. A real unemployment cliff starting September.

Unlike econometric models, such fiscal interference, while creating a short run buzz of sizable proportions, doesn’t actually come with a multiplier greater than one, meaning it was always going to have “transitory” impacts. As such, maybe the economy really is, since around June or July, mean reverting except to a mean state which is far weaker than “everyone” (certainly those in the inflation camp) was told to expect.

Another possible factor, that very “inflation”; oil and gasoline prices, in particular. As history has shown, you want to interrupt pretty much every positive economic trend possible, merely “introduce” an oil price shock and then sit back and wait for the inevitable downturn if not full-on recession.

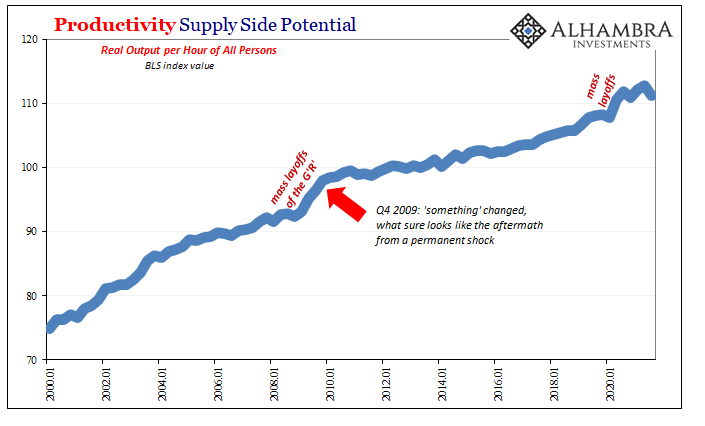

If the baseline private economy’s rebound from 2020 really hadn’t been all that magnificent, then adding the hugely negative influence from pump prices (paid by both consumers and businesses) along with other rising materials input costs and suddenly (not really) labor becomes a much trickier, potentially costly proposition (see: productivity in Q3).

The anecdotes for some LABOR SHORTAGE!!!! are taken for granted at face value as if these represent the “true” state of the economy when, especially since summer began, questions have swirled as caution even slowdowns have instead emerged all over the place.

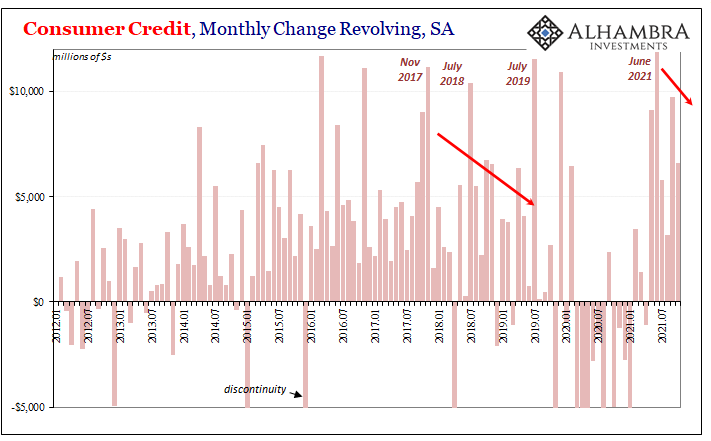

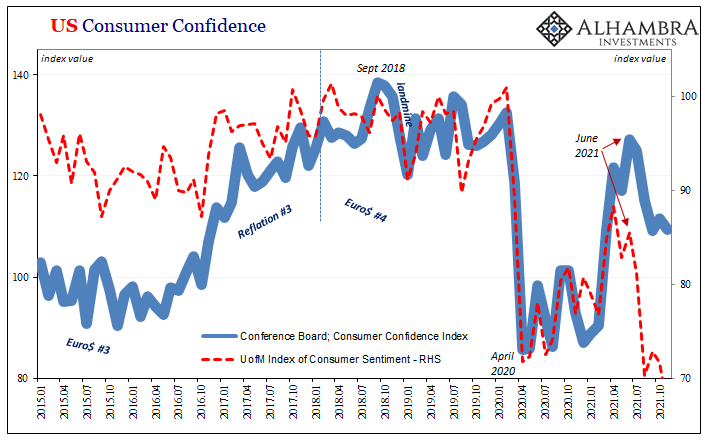

Specifically with regard to consumers (therefore consumer spending), from consumer credit to consumer confidence, it has been the same in each, with both series, credit and confidence, including both sets of confidence numbers, tracing out the same clear inflection point. When?

Yes, just after June:

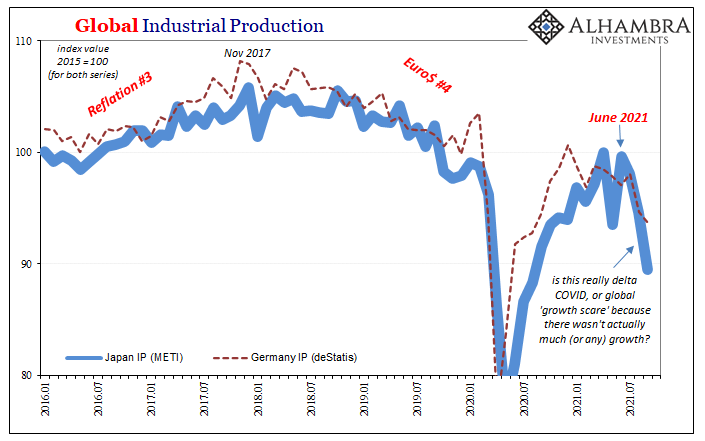

We’re not saying the economy is crashing, only that “something” sure seems to have knocked it off track around mid-year, and not just US labor nor about American consumers; and not only that, the very clear change in the global “bond market” in the few months preceding this appears to have been right on the spot.

Curves have been telling us (anyone willing to listen to them and not the “Fed has rigged bonds” gobbledygook) for nine months to be on the lookout for exactly this kind of economic shift. And with the one for eurodollar futures now inverted very much 2018-ish, they’re saying that the slowdown earlier predicted is now being predicted to slow down even more as 2021 ends in disappointment and 2022 gets started under gathering clouds of widespread suspicion.

The global “growth scare” does indeed include entirely too much of a contribution from the United States. It hasn’t (yet) worked its way into spending on goods (see: retail sales), but that may just be a matter of time (and inventory cycles). After all, there is no decoupling.

In other words, China, Germany, Japan, all the gang’s back together from 2018’s pattern. This time, an even unhealthier dose of energy (costs). The US economy, contrary to popular perception, while it may not be a slowdown as slow as those, the very fact one is showing up in such broad fashion here anyway indicates that’s just a matter of degree not categorical difference.

Neither the US nor the rest of the global economy can really afford anything other than what was supposed to have happened after Uncle Sam’s helicopters – but almost certainly didn’t.

Stay In Touch