With the CPI inching closer to 7% and everyone talking about consumer prices, the FOMC meeting which begins tomorrow can’t be anything else other than inflation. Even if there was something else on the economic horizon, say a material “growth scare”, it’s too late for policymakers since they’d already painted themselves into a narrow corner months ago.

If they don’t accelerate their QE taper now, they risk sending the wrong signals to the economy which everyone says verges on the edge of 1973.

Wait, wait, wait. Isn’t inflation at least something to do with money? After all, the old adage of too much currency chasing too few goods hung around for ages because there was unambiguous historical truth to the saying. You can go back to Isaac Newton and Copernicus realizing there wasn’t mere correlation between money and prices.

In this “modern” age of “enlightened” monetary policy, you’d think QE or the end of QE is some simple matter of liquidity. The Fed “prints” up its “money” until there is enough money having been printed the possibility of a financial backslide, therefore economic retrenchment, is drowned down to nothing in the flood of monetary bank reserves.

Tapering or terminating the “money printing” is therefore just a matter of arithmetic; I mean, after all, it is quantitative easing. No fuss, no mess, just count the flood stage.

At least, this is what you’ve been led to believe; and, despite twenty years of conclusive proof otherwise, what the vast majority of the public still does.

This is why the end of QE ends up being so similar to when the thing begins; ragged, uneven, highly uncertain due to what’s not any part of the formula, even to the point of speculation. There’s no money here whatsoever; front or back, money-less monetary policies.

Suddenly, inflation becomes rather tricky business when it should bear some easy resemblance to Copernican simplicity. If you aren’t in the money game, and the Fed admits it isn’t on occasions like these, what about CPI’s? It used to be you’d check the money supply against standard benchmarks and, voila, the answers practically jump up off the table page.

The truth is policymakers have a choice. They actually do have the option of checking in on the money supply and deriving some of their senseless policies from actual monetary evidence. However, they’d rather continue with the same set of criteria that had previously left Economics in a state of utter befuddlement.

QE’s taper will almost certainly get accelerated this week, practically everyone expecting an announcement along those lines on Wednesday. With last week’s higher high on the CPI, as I started out here the FOMC has left itself no other option.

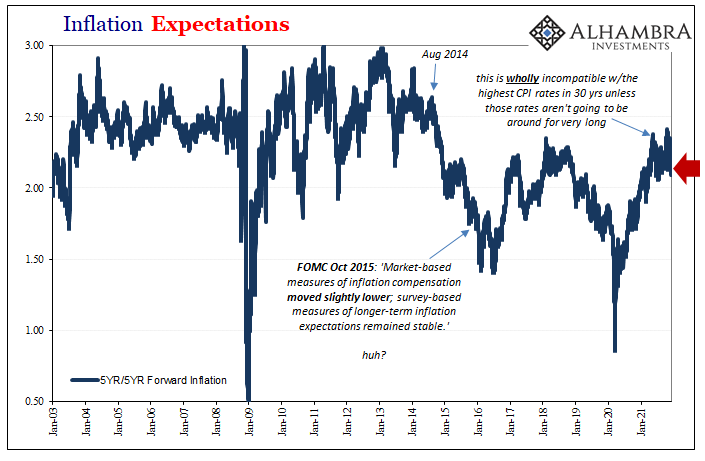

You see, in the absence of technical proficiency in money what we’re told determines inflation is how the economic system dreams on it. Like Santa Claus or the Tooth Fairy, the Inflation Fairy is said to be product of deep adult imagination; we make it real when we believe in it.

In this context of 2021’s supply shock prices, what’s worrying to Jay Powell and his committee is whether or not consumers themselves might begin to normalize their behavior to 7% CPI rates. Even coming to expect regular 5% annual gains would be a huge problem, in theory.

Not whether there’s actually too much liquidity sloshing all over the place in reality, whether you and I think there is regardless if there is or not.

Supply-chain disruptions, labor shortages and climbing oil prices have pushed inflation to a 39-year-high. But attention is now focused on another variable: Do people think inflation is here for a while?

Because people’s expectations can factor into inflation, the answer plays a critical role in determining how the Federal Reserve and the administration manage the rising numbers—and how soon and how much the Fed will raise interest rates.

To counteract this alleged burgeoning shift in expectations, the Fed doesn’t tighten the actual money supply, because it wouldn’t know the first thing how, it intends to fight rising inflation expectations using specific policy signals (first taper, then rate hikes).

You'd think tapering QE was about figuring the *right* level of money/liquidity in the system. Nope.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) December 13, 2021

This stuff is all mush; sentimental nonsense attempting to manipulate emotions.

The quiet part said out loud:https://t.co/YMmcHa4f2c pic.twitter.com/ssnabOnNBZ

The more you get used to high CPI’s, the more you’ll resign yourself to them becoming permanent. To disabuse you of these bad feelings, the “central bank” will pretend it’s doing something monetary so that you replace your feelings about durably higher CPI’s with simple faith in Jay Powell’s tightening fiction counteracting them. Somehow.

Is he actually tightening? No one really knows what QE is or what happens when it goes away; just feel good about the FOMC telling you it is taking care of the economy, so long as you never, ever ask any questions or think too hard on any one of the number of details.

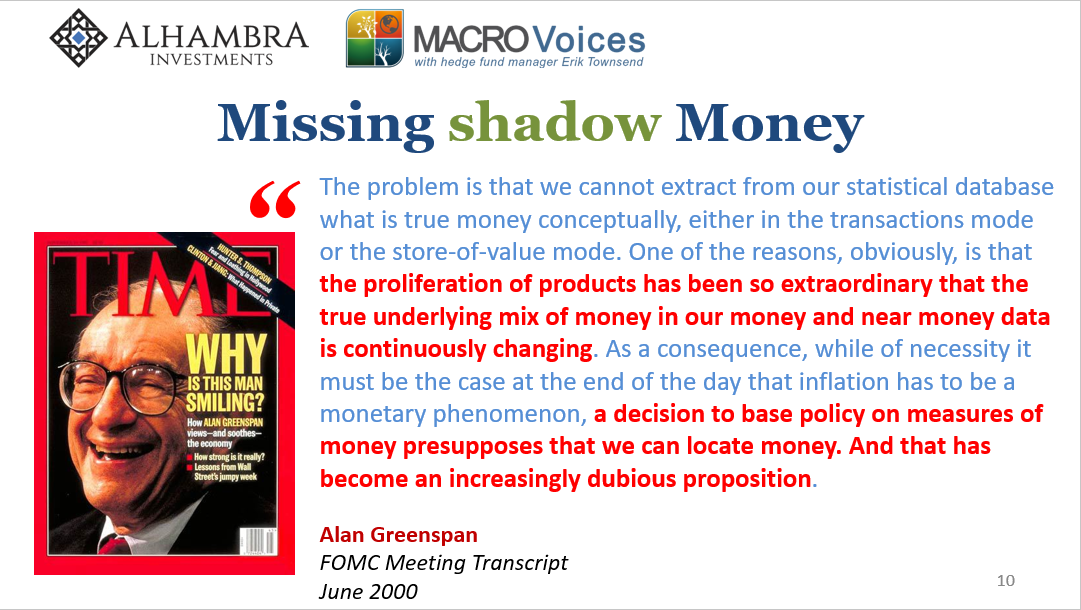

If this sounds like complete nonsense, well, you’re not alone. And if you think I’m making this up, like everything else money-related you needn’t take my word on anything. There are those (probably many) inside the Fed and other central banks who can’t stand how there aren’t any monetary avenues for what’s supposed to be, and is sold to the public as, monetary policy.

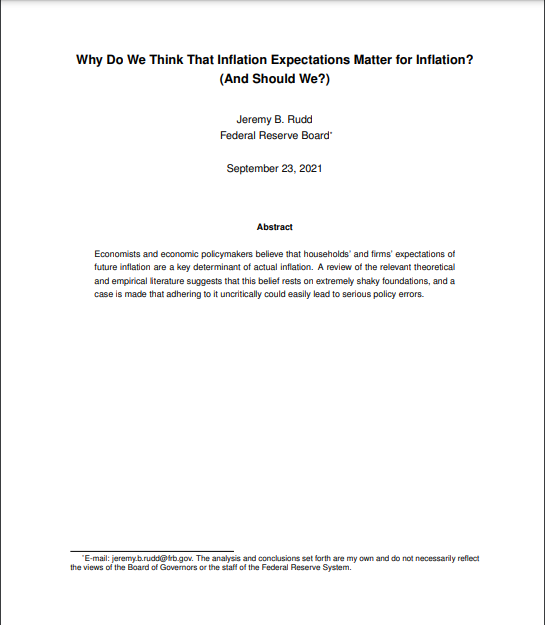

A few months ago, I wrote about one, Jeremy Rudd, who was utterly scathing in his specific rebuke of just this absurdness.

What Rudd said, and showed, was that this “inflation expectations” theory gets cited and regurgitated without anyone ever giving it a second’s pause. Economists and policymakers simply recite the theory despite the fact – yes, fact – Economists and policymakers haven’t been able to produce any useful evidence (Rudd’s work, not just mine) for it; not for lack of trying.

And this apotheosis has occurred with minimal direct evidence, next-to-no examination of alternatives that might do a similar job fitting the available facts, and zero introspection as to whether it makes sense to use the particular assumptions or derived implications of a theoretical model to inform our priors (particularly when the ancillary assumptions of the model are so incredible and when the few clear predictions it makes are so wildly at odds with the available empirical evidence).

The simple truth of the matter is that monetary policymakers don’t do money, so in the absence of doing it the old-fashioned way – which they can’t – Economists have dreamed up this expectations stuff from thin air as a possible workaround. There’s no proof for it, and if you think about this theory for any small length of time you can’t help but laugh at it, but they believe they have no other choice.

Even repeated failures due to over-emphasis on the unemployment rate/Phillips Curve alternative view of inflation left officials perplexed and dazed.

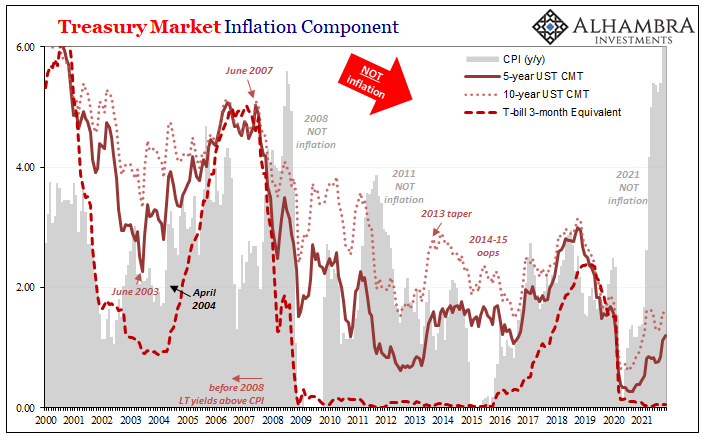

However, just because the official effort won’t ground inflation analysis in any realistic monetary context does not mean you and I cannot.

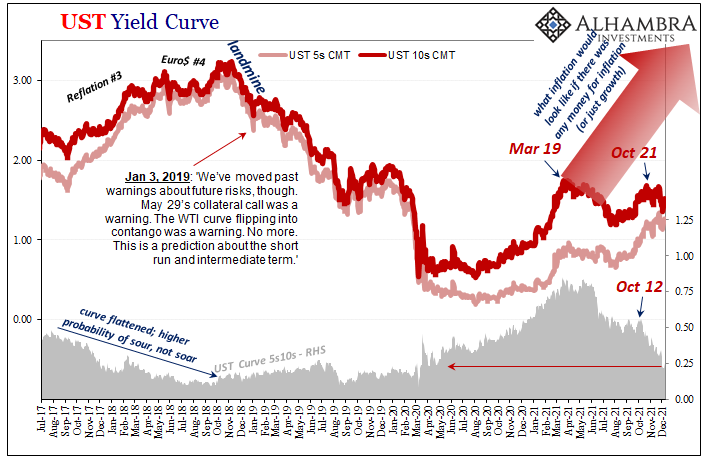

While we don’t have true monetary aggregates available, and such a thing may no longer even be possible, yet the monetary system sends to us straightforward, easily interpreted signals about its condition anyway; and has all along.

The Fed’s accelerating taper is meant to be a reassuring signal to the public in lieu of appreciating the proper set of signals sent to both the Fed and the public alike from inside the eurodollar system.

Almost there, guys. One more step.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) December 13, 2021

Worst real returns since Volcker.

Worst real returns *currently* since Volcker.

So, bond prices still rising, yields falling, curves flattening, one inverted… pic.twitter.com/0AvDHFs9MD

So, this just happened today.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) December 1, 2021

And yes, this is big. Huge. And no, this is *not* clickbait.

Goodbye inflation. I'm serious.https://t.co/vC7ReG78vA pic.twitter.com/nshw3f8eAN

These latter are increasingly confident in projecting monetary conditions – therefore inflation probabilities – that do not align with the assumptions behind tapering QE; not that QE or its taper means anything to that system one way or any other. The Fed’s worried people are getting normalized to high CPI’s when the monetary system is telling the FOMC there’s simply no money for it.

There’s not enough now for legit inflation, more lasting than this year’s supply shock, and a rising probability there’ll be less money left for next year.

We have at our disposal a wealth of real-time inflation and other background data which gives us far more than enough insight into the state of the monetary system we have no need whatsoever to leave ourselves exposed to, and totally dependent upon, the Inflation Fairy.

Central banks, though, they spin a very different story.

Stay In Touch