The BLS released its labor turnover data, or JOLTS, earlier today. There have been two main issues with it, starting with Job Openings (JO) which is widely cited along with the unemployment rate to represent the widely reported labor shortage theory. More controversial has been Quits, lately dubbed in the media as the Great Resignation for a variety of presumed causes.

Beginning with JO, the estimated level of labor demand has been relatively constant up at historic levels (around 11 million, give or take) since last July. And that’s precisely the problem with the series. As discussed in detail last month, these figures make no sense rather having been transformed (in a way not explained) into an entirely different set of relationships with other economic data.

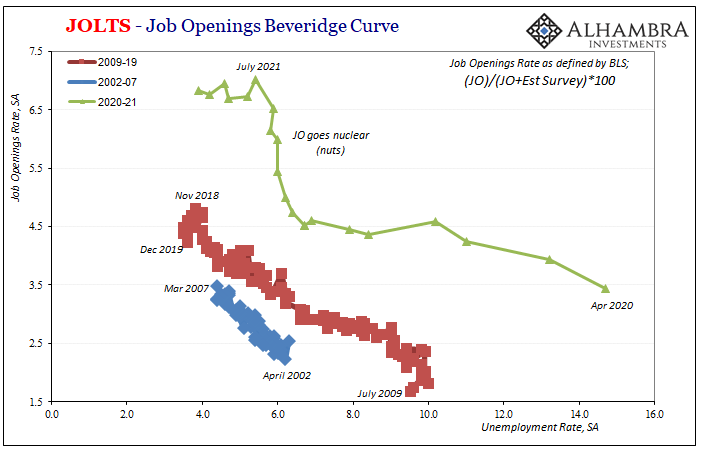

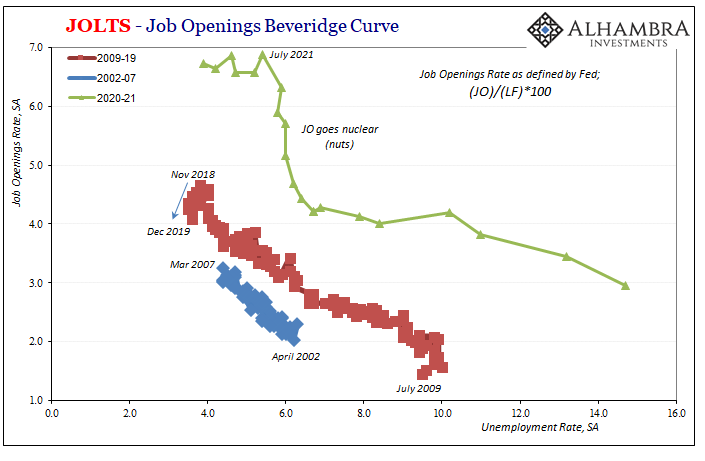

The Beveridge Curve defines, or had, one of those, an key intuitive one, between the estimated demand for labor and its utilization. There should be a relatively stable correspondence but instead the curve since the start of the 2020 recession shifted so much farther out to the right than it had following the Great “Recession” (already a long-ago red flag on JO).

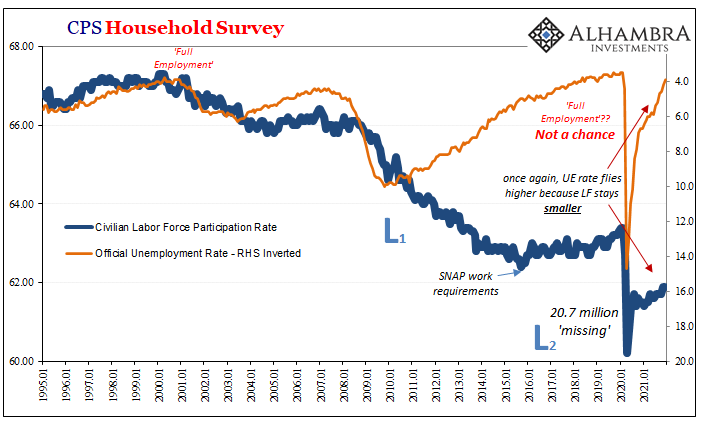

Given the dramatic surge in the BLS measure from the start of last year until July, and then a plateau in it, these results totally break down the Beveridge Curve in both directions at different times: the “curve” went vertical up to last summer, indicating no relationship between JO therefore the Job Openings rate, by any measure, and the unemployment rate; and now it is horizontal as the JO rate remains unchanged for the falling unemployment rate.

The latest updated figures do nothing to dispel suspicions which necessarily follow at what is an inopportune moment for those at the Federal Reserve attempting to justify rate hikes largely on the most charitable interpretations of, and commitments to, this data as well as others such as the equally suspect unemployment rate (continuously plagued by the participation problem).

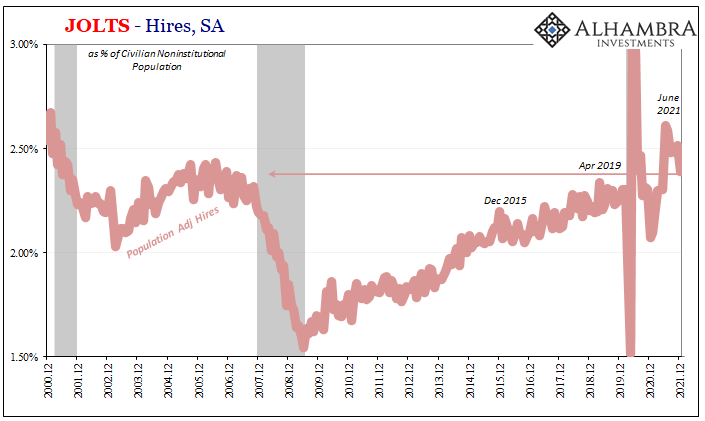

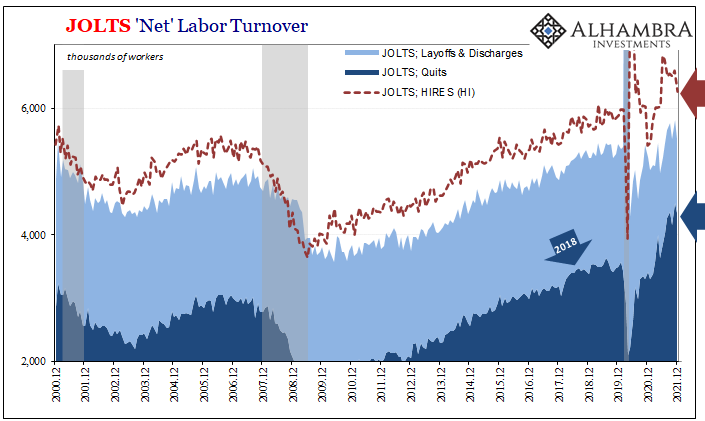

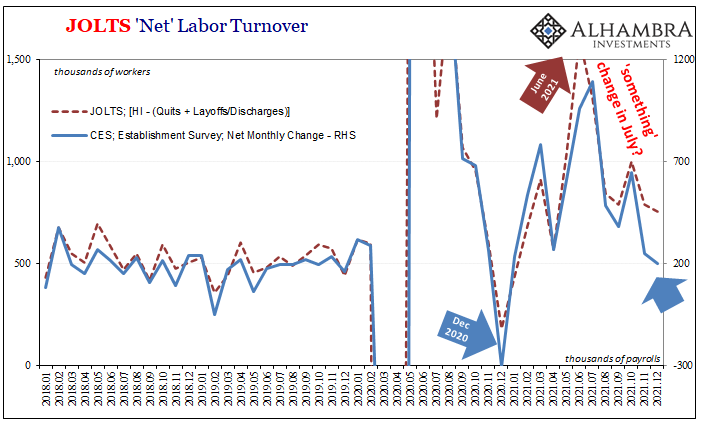

The other hitch that JOLTS helps us identify isn’t quitting rather total turnover, meaning suspiciously weak and low hiring that may yet still be too optimistic. If JO was anywhere close to an accurate picture of real labor demand, then the rate of hiring would have surged by a commensurate amount. It hasn’t; furthermore, it has dropped considerably over the final few months of 2021.

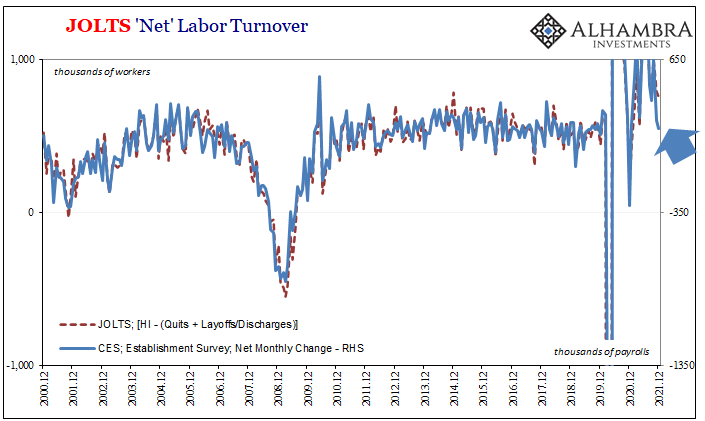

Also noted with last month’s JOLTS, there is a growing discrepancy between total turnover as it should, but hasn’t recently, correspond to the monthly payroll change (Establishment Survey).

Doing the quick arithmetic, you start with a December monthly hiring rate now down below 6.3 million, falling sharply by 333,000 from November (all seasonally adjusted), and subtract 140,000 fewer layoffs and discharges along with 161,000 fewer quits and from the perspective of net turnover the single-month increase in labor utilization “should” have been something like 756,000.

The Establishment Survey gained only 199,000 in December. Even after accounting for the adjustment factor, there remains the same noticeable gap I wrote about last month which only grew wider with this latest update.

It can only be one of four possibilities (already eliminating the low likelihood there’s been more layoffs than what’s been figured): hiring hasn’t been as good as JOLTS estimates; the Establishment Survey has contrarily been too pessimistic; there is a statistical issue with one or both collections; or, more people have been quitting than even the large monthly amounts already tabulated over the past half year.

Payroll data (Establishment Survey) will be released on Friday, of course, and expectations have dwindled for it (omicron already blamed). The consensus (FWIW) currently sees much the same for January 2022 as December 2021 (which probably means the noisy monthly payroll will be a blowout!)

Having made this exact mistake three and four years ago, to see the data for both JO and now questions surrounding HI in even worse shape than the last time should create significant doubts for policymakers as they try to come up with some reasonable guess for economic tendencies; it won’t since taper and rate hikes in reality have little to do with the economy as it might actually be (expectations).

Insofar as that goes, well, decidedly flat yield curve – like 2018 – already looking ahead to an economy that is, has been, and likely will remain as questionable as some of these JOLTS breakdowns.

Stay In Touch