In the earliest days of the eurodollar, its purpose was primarily as a global reserve medium to intermediate and finance trade. To surmount Triffin’s Paradox, this ledger system arose as demand for the reserve currency outstripped the Bretton Woods arrangement’s ability to supply it (because it was constrained by US gold reserves). Rebuilding first from WWII and then an explosion in prosperity that lasted long after, such expanding trade was right in the middle of humanity’s greatest wave of globalization.

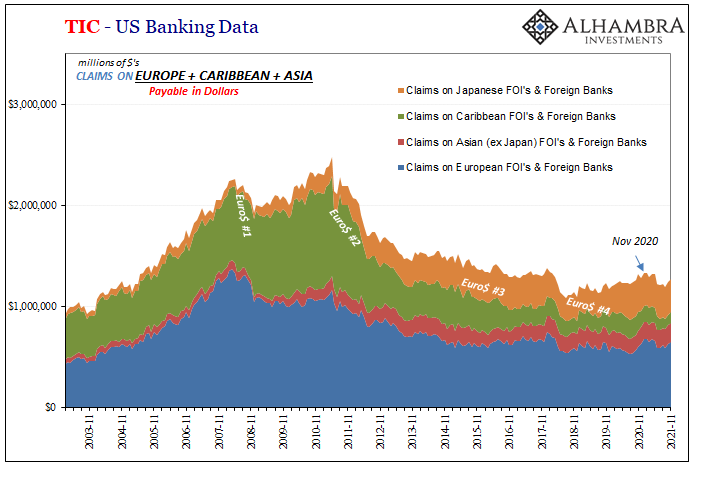

Over time, especially in and after the eighties, the eurodollar took on the “other” focus of any reserve system: financial flows. Some call it “hot money”, others direct investments. More and more as the 20th century drew toward its close and the eurodollar system expanded more frenetically, merchandise trade took a back seat to the unrivaled potential, and greed, of raw finance.

Even as the US trade deficit itself exploded, it had been the hot money surge and what boomerang-ed from it back into the US which caught even Ben Bernanke’s over-confident notice. What he laughably called a “global savings glut” was eurodollar excesses in both channels, though by then far more finance than merchandise.

Since eurodollar money is by definition offshore, the “amount” of “money” flowing through it isn’t dependent upon the US trade deficit; that offshore eurodollars are merely a byproduct of the US sending dollars overseas because America imports so much more than it exports.

The US merchandise deficit is not the only or even primary source of eurodollar money; finance is and it already originates on the outside (offshore from everywhere). The dollars are instead created, or destroyed, from the outside and more so predicated on financial considerations many times having little direct connection to the US trade situation (though there is some feedback, which we won’t get into today).

Since China has been the primary beneficiary of both kinds, we might look into its specific local conditions to give us a sense of what could be happening in the larger, hidden shadow spaces more specifically tied to financial eurodollar flow – with a particular interest on what might have really taken place last year.

Everyone says too much money, a flood therefore global inflation like nothing since the seventies. Actual data as well as markets have all come down on the opposite side of the spectrum.

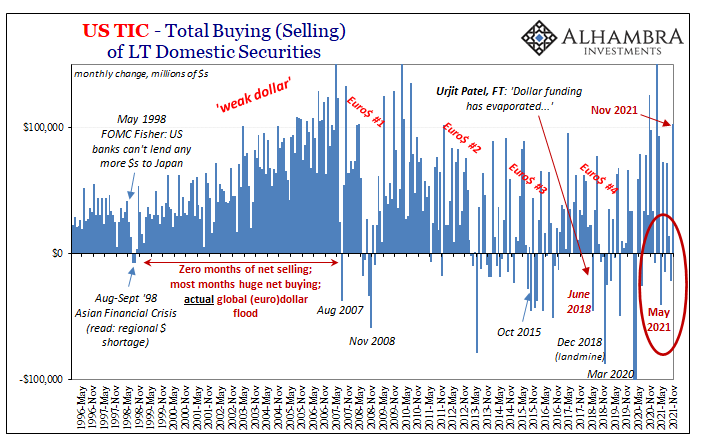

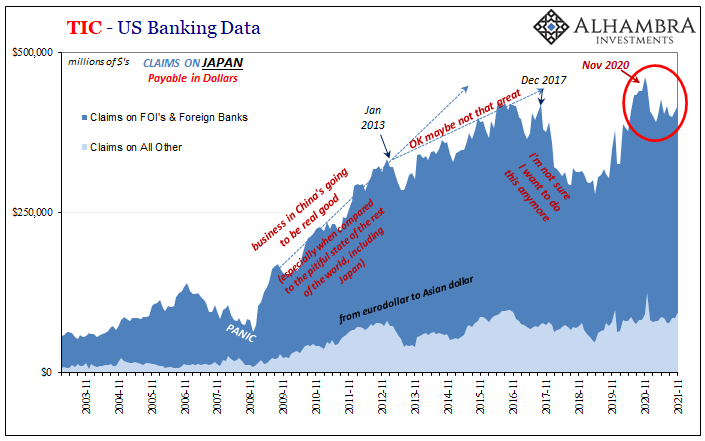

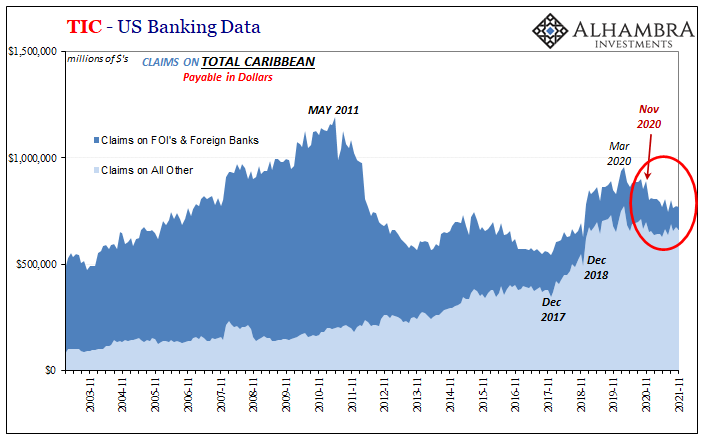

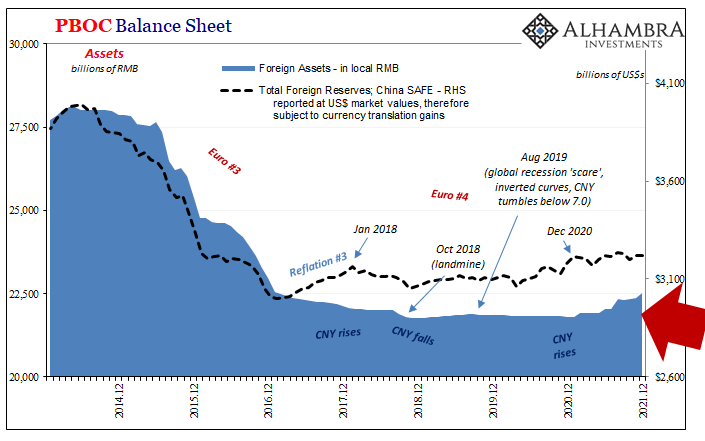

We want to see if we can connect a few dots; things like TIC which showed a dollar shortage rather than a continued “flood” as Jay Powell had asserted in 2020, along with CNY which broke its trend way back last January. There’s also the lack of follow-through on the PBOC’s balance sheet (though some contend Chinese SOB’s are, for unexplained and, to me, anyway, irrational reasons, hiding dollars offshore).

Can we figure out those “conundrums” given that we know far better in China’s huge increase in merchandise trade surplus?

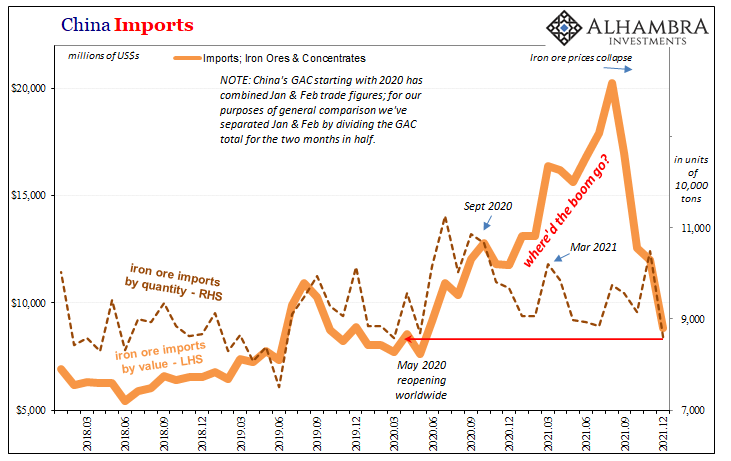

A good part of that is the money illusion, too, which for our purposes is included. Since we’re attempting to back out eurodollar flows from what we can reliably see (and we don’t intend to be precise), what matters is the amount of indicated dollars flowing in both directions regardless of relatively less impressive volumes (see at the bottom: iron ore as an example).

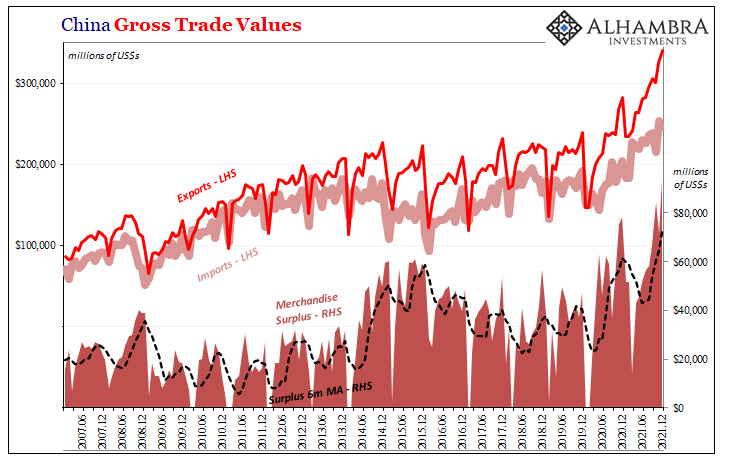

The easiest past of the external monetary equation to identify is China’s trade surplus and its recent historic expansion. For 2021, it had been unprecedented:

Far more dollars coming in due to exports than any dollars going out paying for China’s imports (recognizing that not all Chinese trade is conducted via eurodollars, but the vast majority is so we are generalizing). This would seem to confirm CNY’s rise.

There must be more to it, though, and only if we reconcile the part of the equation we can’t see. There are more dollars heading to China for goods, sure, but this might only be partially offsetting a possible dollar shortage related to financial eurodollar constraints evident in other data like TIC.

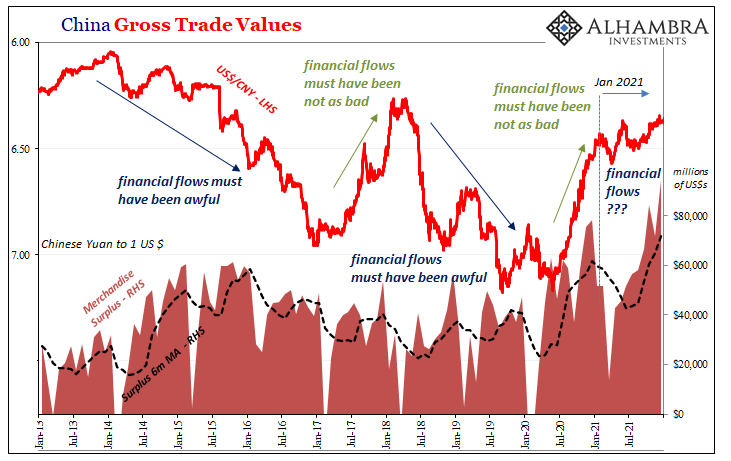

If we add CNY’s exchange value as a proxy for the overall mix of financial as well as merchandise eurodollar flows, and then overlay what we might reasonable assume as strictly merchandise conditions taken from China’s overall merchandise surplus, what’s left – process of elimination – might be a reasonable if still imprecise remainder suggesting strictly financial flows (since we can’t use SAFE or PBOC data, each clearly artificial and engineered for “some” reason or reasons).

Start with 2014. CNY goes down right from the beginning of that year – even though China’s merchandise surplus goes the whole opposite way. It doesn’t matter that the primary cause was suddenly weaker Chinese imports relative to exports, throughout 2014 right through 2015 by merchandise flows alone China was obviously obtaining more dollars than it had at any time in its history.

Yet, especially in 2015, CNY crashed despite those inflows, doing so in obviously financial – August 2015 – ways. Therefore, falling CNY notwithstanding much higher dollar inflows from its trade surplus leaves us only with what must have been a truly colossal eurodollar drain via the “hot money” financial channel; China’s goods surplus we did see could only minimally offset the financial deficit we really can’t, at least not directly (though the huge declines in foreign reserves reported by PBOC and SAFE data are consistent).

In 2017, the merchandise surplus failed to rebound (as global prices raised the dollar costs of Chinese imports relative to exports) so as CNY went higher it at least indicated the potential for positive financial flows during globally synchronized growth. The fact these didn’t show up in any size at the PBOC leaves unanswered questions beyond the scope of today’s purpose.

One year later, 2018, CNY’s fast-moving collapse after April 2018 might then be explained by eurodollar financial destruction (India’s Patel in June: “dollar funding has evaporated”) now combined with a falling merchandise surplus. Financial flows disappeared as Euro$ #4 took hold, only this time unlike 2014-15’s Euro$ #3 there weren’t any let alone huge merchandise inflows to even modestly counterbalance the loss of the other kind.

So far, so good.

The rebound from the COVID recession initially makes visible sense. Exports outstripped imports from mid-2020 which meant dollar inflows through goods trade while leaving the possibility of positive financial inflows, too, though not anywhere close to the claimed global flood from the Fed’s operations.

CNY’s 2020 near 45-degree ascent pretty consistent.

Right from the start of 2021, though, something obviously changed. CNY still exhibits a small upward bias – to this day – but nothing like the rocket-like ascent from the year before.

This despite that massive, historic increase in China’s merchandise trade surplus last year. Something not immediately apparent appears to be missing.

More trade dollars flowed into China than ever before, yet CNY’s trend has changed in another direction. It isn’t falling, but it’s far more flat-line than anything like 2020’s unchallenged vigor.

Process of elimination, then, is this extraordinary amount of trade dollar inflows partly compensating for what likely should therefore be considerable eurodollar outflows via the financial channel? It wouldn’t appear to be quite as negative as it had been in 2014 or 2015, yet enough to swallow up an even larger trade surplus and the “money” which comes with it.

If true, these latter implied outflows would be highly consistent with the global dollar shortage shown up in TIC, UST yield curve (flattening), deflationary probabilities, etc.

The implications for 2022 are: 1. What happens if the eurodollar financial pressure/outflows from China/gross monetary retrenchment proves to be yet another of the same type of global monetary cycle as those prior? The global dollar shortage persisting let alone intensifying would mean “headwinds” for this year; 2. What happens specifically in and to China if, maybe when exports begin to normalize as a consequence of activity (volume) decelerating (compared to artificial highs particularly in American goods demand last year) along with the potential for prices to perhaps simultaneously reduce the money illusion associated with them?

If it’s anything like 2018 and Euro$ #4, the prospect of a lower merchandise money surplus might convince the Chinese at the very least to begin buying fewer imports if only to save on expending eurodollars to pay for the latter. Otherwise, like Euro$ #3, they risk having to dip into foreign reserves again thereby repeating economic results China’s authorities clearly intend to avoid (managed rather than freefall decline).

Maybe none of this happens and 2021’s negative eurodollar financial background fades into obscurity as nothing more than some unexplained trivial curiosity. The data, and markets, however, they are suggesting this far less likely.

Global headwinds are and have been indicated in a number of places, including, I believe, China, eurodollar, and its centerpiece financial flow. Even though the US is “exporting dollars” from its own historic merchandise deficit, the offshore world of financial eurodollars seems to be doing something else.

Since the sixties, finance is the thing.

Stay In Touch