The most common explanation for UST repo fails is that short sellers become an imbalance in the market for Treasuries. Convinced (isn’t everyone?) interest rates have nowhere to go but up and these instruments are doomed, therefore ripe to profit from the destruction, short selling sharks supposedly swoop in. Since they’ve borrowed UST’s they don’t own, the herd is susceptible to any reverse in psychology.

When it leads to a rush for short covering, we’re supposed to believe what follows is a rash of repo failures.

Like a lot of individual pipes within the monetary plumbing, it’s a nice story which makes it seem like there’s nothing more here beside the occasional speculative excesses, something not at all out of the ordinary even in the healthiest markets.

What if instead a swarm of repo fails could be a sign of structural, systemic shortfall in monetary capacity for one of the most crucial elements in the whole global (euro)dollar architecture leaping up out from the shadows? Totally different vibe.

There are, sadly, any number of examples which amply demonstrate how repo fails align exactly with these deflationary outcomes rather than UST traders who are falling all over themselves to bet on whichever Fed Chairman (they all say the same thing) declares to the world how rates must force higher.

So, what is a repo, and why might it sometimes fail?

In any repurchase agreement, or repo, one party agrees to “sell” a security to another while simultaneously agreeing to buy it back (repurchase) at a later time (typically the next day). Why would anyone do this? Because a repo transaction isn’t really about the sale and repurchase of a security, rather it is basically a collateralized short-term loan.

Flip the perspective around, the first party actually agrees to borrow cash (“sell” the security for cash) from the second party who gains security by holding the liquid financial instrument during the arrangement. The following day, or at whatever later maturity (term repo), the first party pays back the loan, with a bit of interest, the second party delivering the liquid financial instrument (repurchase) in a return to its owner.

Title over the collateral never changes hands; in fact, the cash borrower only concedes limited rights from which the cash lender may seize and sell the collateral if the cash borrower doesn’t pay back the loan.

However, there are other times when other factors end up creating some headaches. Should the cash lender, for example, decide that it doesn’t want to give the security back the next day (or when the transaction term expires), letting the cash borrower keep the cash, this would constitute a “failure to deliver”, or repo fail.

Yes, there have been times when collateral becomes more “valuable” than cash.

One reason why is, believe it or not, other kinds of repo fails. Sometimes – a whole lot of times – instead of counterparties exchanging cash for collateral, and then unwinding cash back for collateral back, they might instead exchange one form of collateral for another (securities lending/transformation). As above, should one or the other decide not to go through with the agreed and scheduled reverse of the transaction, it’s also a repo fail.

Why, how, what…huh?

Collateral is, quite against the original intent of risk-free lending, totally fungible. Securities are exchanged, reused, repledged, and, yes, rehypothecated in untold quantities. Rather than think about repo arrangements as a series of individual transaction, realize that financial institutions are taking in cash as well as collateral across vast portfolios and operations, with each also going out for any number of profit-making or risk-controlling reasons.

Very much like the concept of money velocity, in collateral it begins with rehypothecation. Collateral often changes hands many times over the course of a specific period of time. These “collateral chains” therefore form the backbone of the repo market. Without them, collateral doesn’t flow and that can lead to serious breakdowns not just in repo but across the entire financial landscape.

The Autumn of 2008 was only the most extreme example of such.

Another example was March 2020 (the true version, not the one where the disheveled janitor portrays himself as the hero).

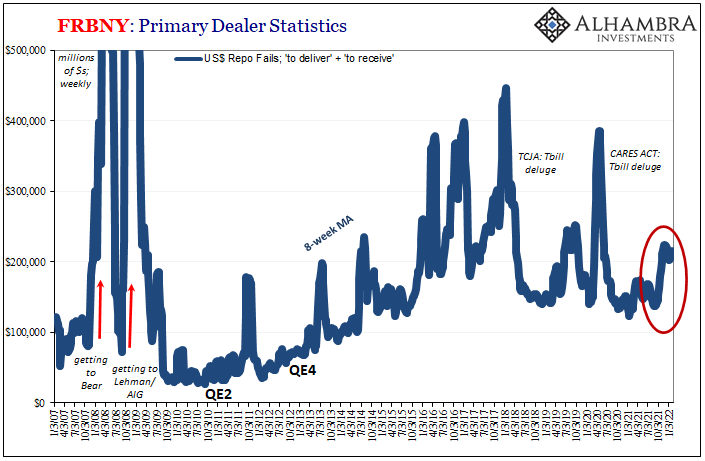

Unfortunately for us, the only real source of data on repo fails is FRBNY, a branch of the Fed which doesn’t really appreciate what the incomplete data it collects portends (or maybe they do, realizing how failures here hit so close to home, so to speak). What it collects is information gathered only from primary dealers specifically, leaving most of the repo market out of it (the majority of repo is bilateral and bespoke, and not all collateral and repo dealers are primary dealers).

Furthermore, the FRBNY figures do nothing to separate fails due to “regular” repo from any that might arise as securities transformations gone wrong. Any information as to the latter would be especially helpful.

Too frequently, collateral chains have been disrupted by risk-aversion in that end of the key repo spectrum; without risk-taking on the part of dealers, meaning a higher degree of reuse and re-pledging, those collateral chains can contract leaving collateral users to scramble to find other ways to maintain their use of collateral.

Including failing to deliver collateral which technically doesn’t belong to you.

As collateral chains shrink, it also creates higher demand for the better-quality forms of collateral – based entirely on the perceived liquidity characteristics of whatever instrument. Thus, US Treasuries are the best of the best, and T-bills the best of the best of the best (far less price risk). Prices for each go up, or don’t go nearly so far down, when scarcity has become serious.

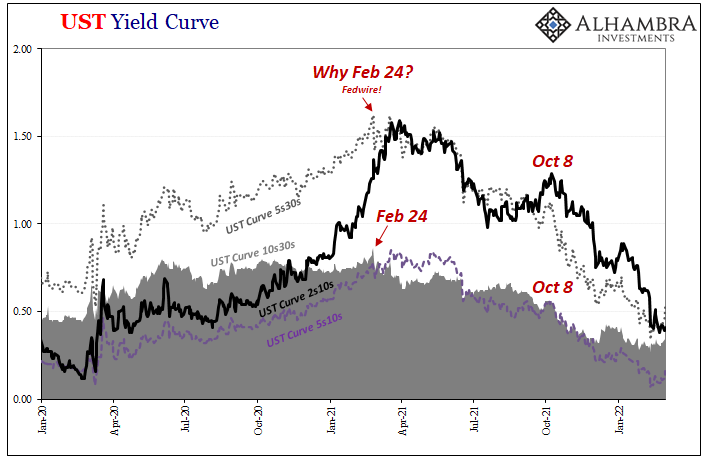

Scarcity of collateral – being exhibited in a number of possible ways, including repo fails – must be factored in long run bond yields (as well as T-bill prices) as deflationary potential even if it doesn’t immediately present total breakdown along the lines of March 2008 or even March 2020.

The potential for disruption is enough to recalibrate these various curve dynamics; higher probabilities for scarcity becoming a shortage that trips up the global financial and economy marketplace.

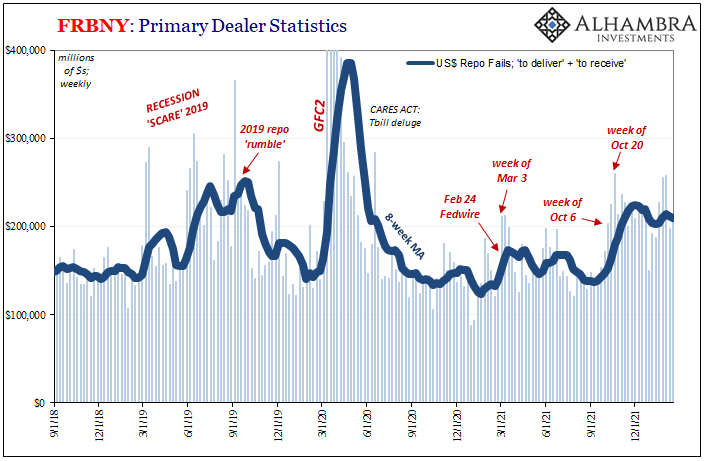

When repo fails abruptly increased for the week of March 3, 2021, was that because short sellers had grown too numerous? At first glance, it might seem so. After all, bond yields at the time were rising quickly, prices for Treasuries falling, which almost surely had enticed many to try their hand at this kind of speculation.

The week of March 3, however, also just so happens to be the one immediately following February 24 and 25: yes, once again, that Fedwire business and then the messy 7-year auction when dealers were notably absent still trying to catch up from their previous day backlog of uncleared and not-yet-settled transactions.

Given the way the entire Treasury market behaved in the wake of February 24/25, it was decidedly in the direction of deflationary potential. If short sellers were having their wildest dreams confirmed, as the mainstream had said at the time, what would have otherwise caused them to suddenly cover, all at once, leading to the noticeable increase repo fails?

On the contrary, if what happened on February 25 was consistent with inflation expectations underlying the short selling idea you’d expect the opposite; shorts to go more short, less covering, because it was unfolding in the way they’d set down positions.

In fact, nearly everything in the bond market – including, after only a few more weeks, the direction of nominal yields – points to rising deflationary potential in the immediate aftermath of Fedwire Feb 24. Repo fails, too.

The yield curve began flatten (and never stopped) at the long end where inflation expectations are more sensitive; therefore, deflationary expectations, too, given how repo fails indicating collateral shortage after dealer risk-aversion just may have contracted collateral chains “too much” in the aftermath of that specific event.

Not only does Feb 24/25 show up on all these charts, so, too, does early October. Very prominent also on the yield curve (October 8) and, sure enough, repo fails once more.

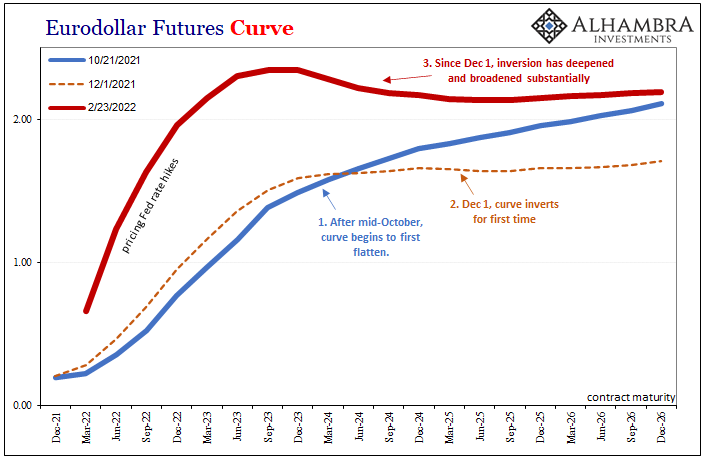

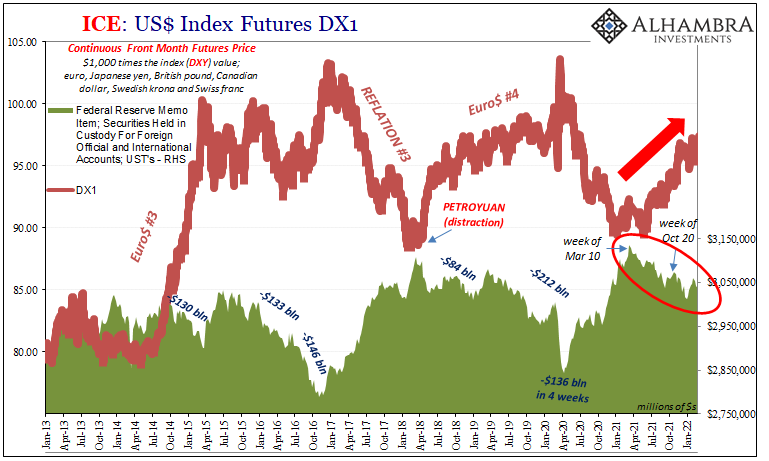

By the week of October 20, fails had hit their highest since June 2020, at that same moment (October 21) the eurodollar futures curve, for one, began its flattening twist to the point of inverting by early December and now remains seriously upside down. Repo fails since have stayed consistently high – higher on a sustained basis than they have been in years – during that very same timeframe.

“Something” isn’t quite right in repo collateral. I once called it a “fails swarm”:

The mainstream still talks about the situation as if there are “too many” UST’s despite the debunking in UST prices, but what really happens is dealers hold on to UST’s for their own reasons or purposes which deprives the rest of the market of its more fluid collateral operation.

For foreign offshore repo participants seeking collateral, if you can’t borrow or transform from primary dealers who choose to hoard it, where might you go instead to obtain the required pristine securities? Your local central bank might be willing to help especially if it holds quite a few already, which answers in part why Treasuries tend to leak out of the Fed’s custody during these same periods.

Yet another consistent collateral/deflationary potential datapoint. In 2021, Fed custody of foreign-owned (mostly by central banks) UST’s has been declining since the week of March 10, with another leg down starting from the week of October 20.

While last year was uniformly billed as the year inflation showed up and broke loose, it was actually rising deflation for the vast majority of those months in the money where it truly counts. Collateral scarcity related directly to that negative potential, way, way too many things to be just random coincidence.

Or Jay Powell-friendly speculators temporarily short covering before the bond market blows up.

Stay In Touch