This week will almost certainly end up as a clash of competing interest rate policy views. Everyone knows about the Federal Reserve’s upcoming, the beginning of what is intended to be a determined inflation-fighting campaign for a US economy that American policymakers worry has been overheated. The FOMC will vote to raise the federal funds range (and IOER plus RRP) for the first time since December 2018

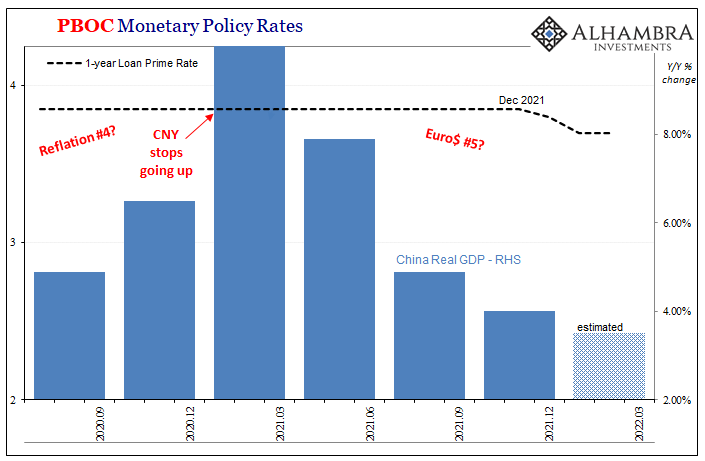

Over in China, however, it’s nearly certain to be the opposite. The Chinese central bank, PBOC, has already cut several of its benchmarks dating back to last year. In December 2021, authorities there surprised many (vast majority) of Western observers when they reduced required reserves (RRR) and then the MLF leading to a decline in the LPR (loan prime rate).

The latter was followed by a second reduction in January. Last month, the PBOC held off on a third rate cut hoping that the Chinese situation had, to use Li Keqiang’s term, stabilized.

According to the latest from China’s Financial Statistics Report on lending during February 2022, those hopes were dashed.

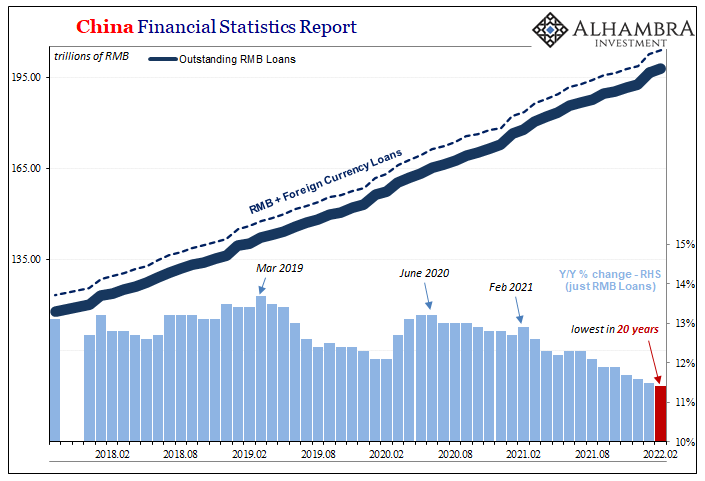

Overall RMB loans to domestic borrowers increased 11.4% year-over-year, rising to 197.9 trillion rmb. These numbers may sound solid, but that annual growth rate was less than anticipated while also representing the lowest yearly change in just about two decades (May 2002).  Worse, this continues a trend which showed up – like a whole bunch of problems – in March 2021. Total RMB loan growth has been steadily decelerating for an entire year already, with PBOC policy shifts including those rate cuts mentioned above not producing the “stability” government authorities have been publicly seeking.

Worse, this continues a trend which showed up – like a whole bunch of problems – in March 2021. Total RMB loan growth has been steadily decelerating for an entire year already, with PBOC policy shifts including those rate cuts mentioned above not producing the “stability” government authorities have been publicly seeking.

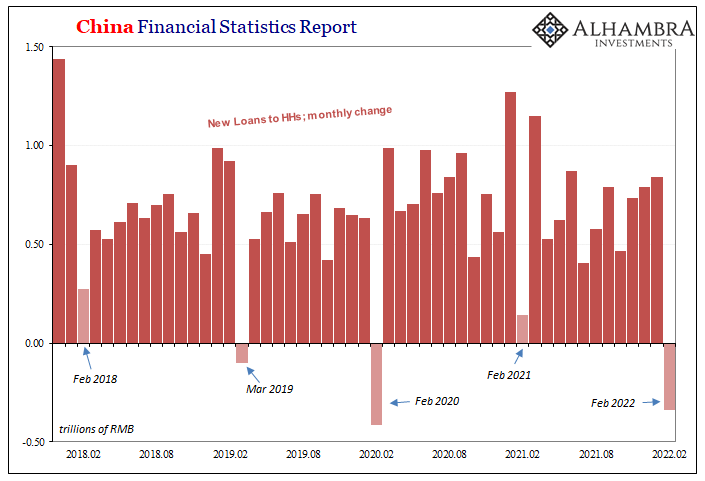

On the contrary, the February Financial Statistics Report contained a nasty downside surprise which partly explains the topline RMB loan figures. Loans to households declined sharply, falling by 336 billion rmb from January (below). Though January to February is typically a seasonal low point as far as new lending is concerned, this year’s change is far closer to February 2020 (COVID lockdown) than February 2018 (starting into Euro$ #4) or even March 2019 (the downturn from Euro$ #4).

The reason for the decline in loans to households was the first ever drop in long-term credit for the category – a proxy for mortgages therefore a worrisome sign about the real potential for the Chinese system given its (former) reliance on real estate for much of its upward growth and ability to better weather volatile global economic factors.

As a result, it is now widely expected the PBOC will announce more rate cuts (MLF most likely, and very likely another RRR reduction, too) this week before early next Monday morning (Beijing time) a third drop in the LPR.

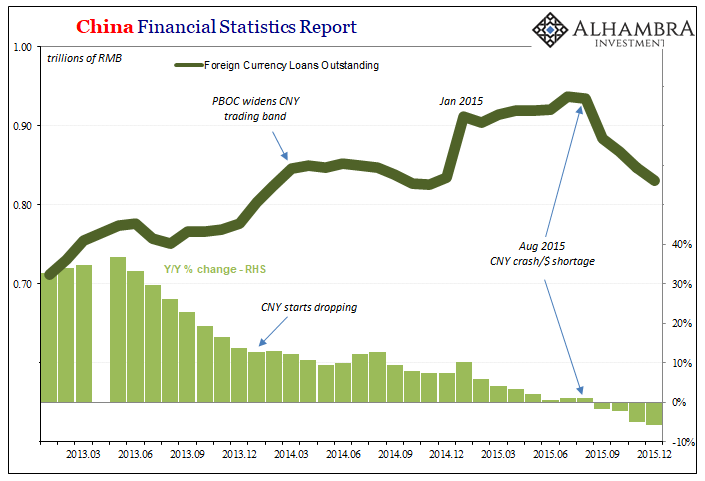

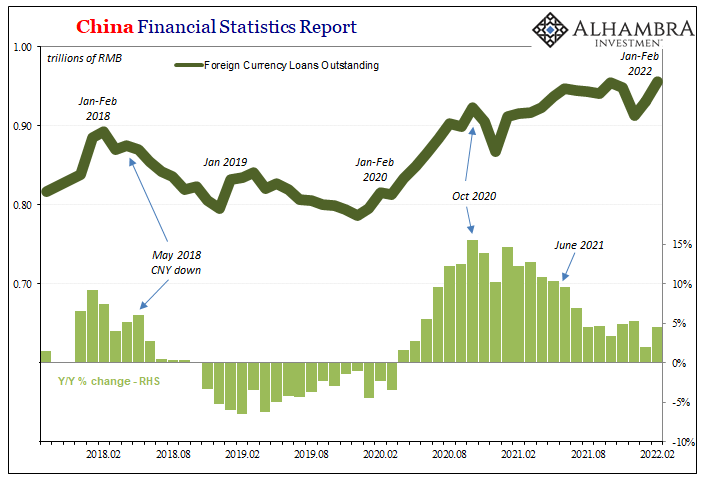

China’s Financial Statistics also contain more data to complete a still-developing global downside case – foreign currency loans to domestic Chinese borrowers. Though it is a much smaller subset of total financial credit, the trend(s) in lending by foreign currency merely reinforces the links between what otherwise might appear to be distinctly different systems.

Going back two prior “cycles”, from the middle months of 2013 (the “summer of SHIBOR”) right onto 2015, the dramatic swings in foreign currency loans matched near perfectly the full-on financial and economically destructive development of Euro$ #3 and all its various symptoms – especially its worst parts in the final few months of 2015.

Begun a year and a half prior, foreign lenders clearly became more and more adverse just as similar indications (dollar shortage) were expressed in US$ markets worldwide – from flattening yield and money curves, up to and including the US$’s exchange value against CNY and many others.

While many here in the West remained utterly convinced of US economic and financial risks tipped toward overheating and inflation throughout 2014 and even into 2015, this had been another clear and corroborating sign of the opposite potential worldwide (eventually).

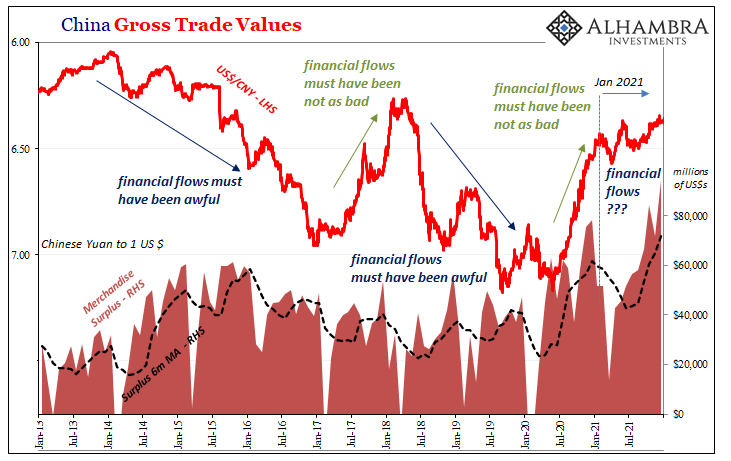

The setup and reversal in 2018 (Euro$ #4) was even more extreme, including the downdraft in CNY and the global consequences which followed in a matter of months.

The Chinese then moving opposite to Mr. Powell (like his predecessors) were dealing with weakness and worse which has consistently reached China first before plowing into the rest of the global system.

Markets sided with China, or at least understood what was happening to the Chinese was almost certain to happen here before too much longer regardless of the Federal Reserve’s oft-stated confidence in its projections going the other way.

As you can see above, foreign currency loans into China have noticeably decelerated again going back to last summer (along with a bunch of other things), indicating global eurodollar setbacks already building throughout the last half of last year (consistent with other data such as TIC).

Remember, too, China’s trade surplus therefore merchandise dollar inflows remained at historic levels meaning that foreign currency credit inflows are to some significant extent higher than they would otherwise have been on a financial basis alone. That’s also true for the January-February months when many of these loans get done, typically a positive start in them each and every year (2022 no exception).

Put all these together, and you’ve got China’s credit system continuing to decelerate dramatically along with a global credit/money proxy indicating the same for the world’s financial shape as a whole. The second half of 2021 wasn’t a continuation of massive inflation potential, rather it was a downside economic drive which didn’t stop at the end of the calendar.

On the contrary, there’s every reason to believe the downside risks are what’s rising even if alongside the US CPI, which is why Chinese policy rates will keep moving in the “wrong” direction sparking what should be a very troubling disconnect. Though there may be an ocean in between, despite the Fed’s intentions there isn’t actually much economic or financial distance.

Only time.

Stay In Touch