It’s an ominous though hardly surprising development. This has been shocking for those involved. Many if not most shipping companies had convinced themselves that once Shanghai and China’s vast harbor facilities were opened back up there’d be at least a mini-boom, a surge in activity for the world (America) to make up for lost time.

Container rates were widely anticipated to rise after having dropped precipitously from February. Neither that nor the activity boom has materialized. Container prices have continued to fall, as have other freight rates while here comes the demand destruction:

There were more signs this week of inventory surpluses and a resulting slowing in orders by major retailers suggesting a decrease in demand – at least for certain goods – as consumers shift spending to services or to the inflated costs of necessities, or both.

A recent survey of freightos.com marketplace users shows that SMB importers are experiencing these trends too: More than half of respondents report they’ve placed peak season orders early in the hopes of building inventory. Two-thirds said they are already experiencing a decrease in demand, with 84% of those attributing that dip to inflation.

I had asked this question before: all the while Shanghai was walled off by Xi Jinping’s cruel authoritarian impulses, what if retailers and wholesalers in the US and elsewhere had used the lockdowns to just cancel prior orders? Hey, we’re all full to the brim with inventory anyway, while you’re closed up we don’t need the stuff anyway. We’ll get back to you…

Here’s a thought: what if retailers and wholesalers in the US have instead used the Shanghai mess to just cancel orders? Hey, since you all are closed anyway, just don’t bother. Save us the fuss.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) May 26, 2022

That's kind of what China's last PMI data was hinting.https://t.co/QJooEsoMaT pic.twitter.com/jO3chnJaHc

T R A N S I T O R Yhttps://t.co/5pvX6ihqGe

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) June 18, 2022

The Big Box Big Guys Target and Walmart had already hinted as much, before Target basically came out and said it.

Now the data is confirming how it wasn’t just one or two American retailers here or there, the inventory cycle is really beginning to bite – just as it has been predicted.

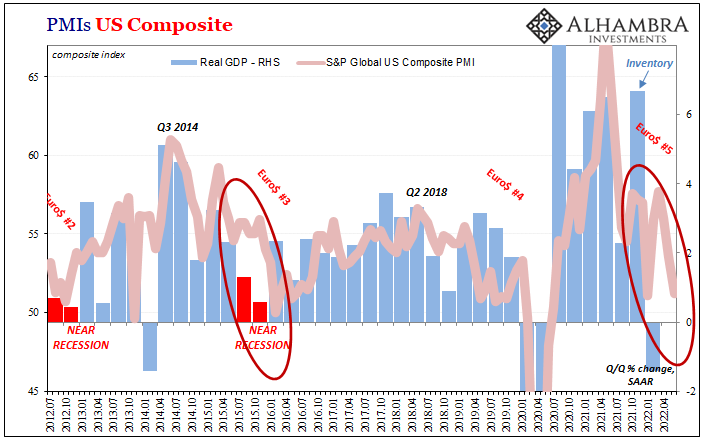

Today, S&P Global (formerly IHS Markit) reported alarming drops in all of their sentiment indicators. The services one down, manufacturing way down, therefore the composite basically the same as January 2022 when, you might recall, a big chunk of particularly the US Northeast was partially locked down to omicron overreaction.

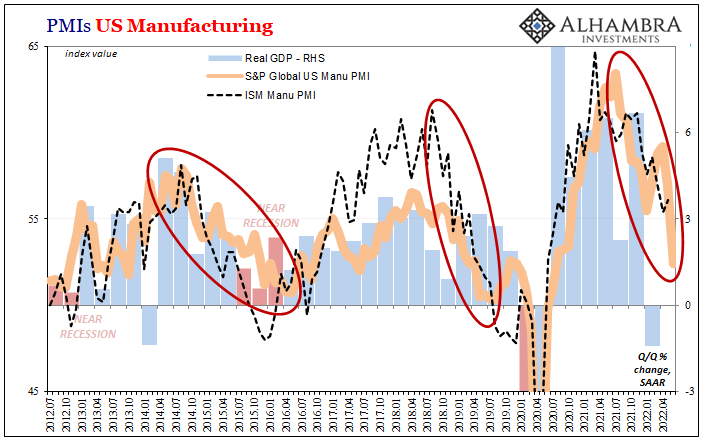

While we shouldn’t understate what the weakness indicated in services means already and portends for the near term, the big one is how the manufacturing data here simply fits into the emerging pattern first priced many, many months ago by markets which are now several steps further ahead in forecasting only more, and worse, of this just ahead.

According to SPG, its manufacturing PMI was expected to ease from a concerning 57.0 in May 2022 to around 56.0 for June. Instead, it tanked, falling to 52.4 and was only saved from much worse by still destructive price categories. Both production as well as, yep, new orders fell below 50 – contraction – each the first time since the bad days of 2020.

While some excitedly point to the overall level of these sentiment numbers, that’s not really the story here. Instead, it is the direction, the persistence of that direction, and lately the speed at which the numbers are all dropping in going this way.

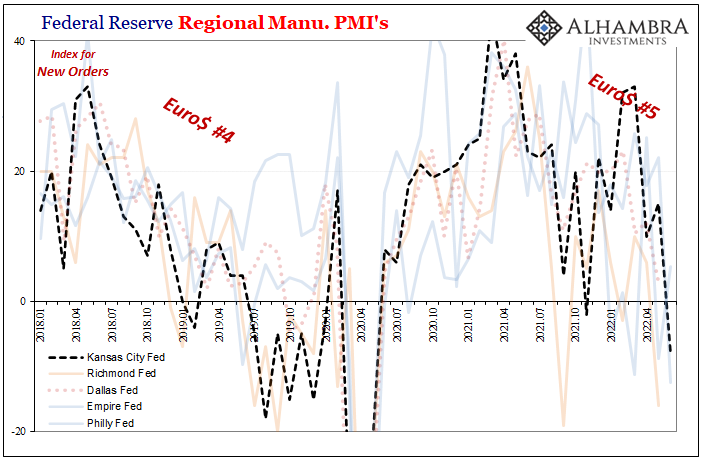

To punctuate all those, Kansas City’s Fed regional manufacturing survey echoed these other numbers. This one out of the other five I follow closely had been the outlier, the one hanging on to at least the idea of only a limited slowdown.

For June, the overall composite dropped from 23 to 12 (saved, again, by non-production components), the output index falling to -1 while, yes again, new orders crashed to -8 from 15.

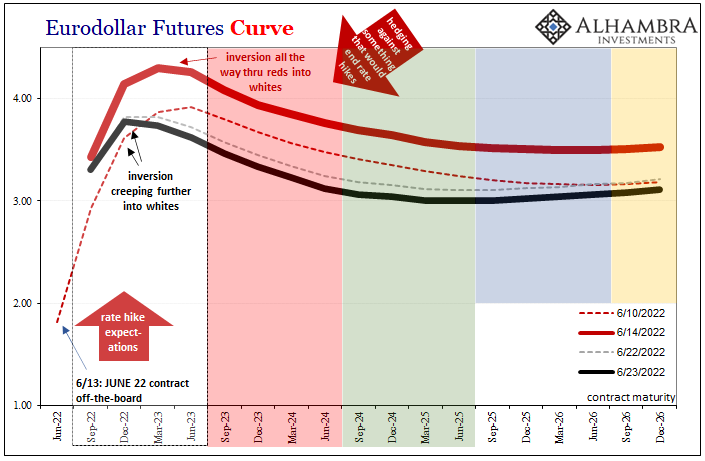

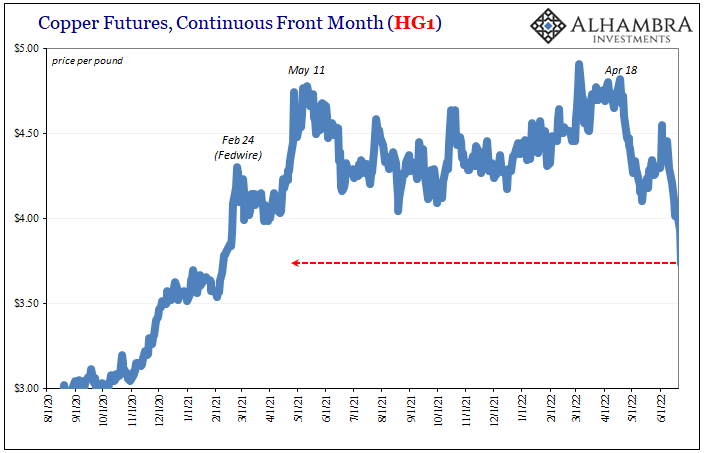

No doubt the deflationary forces behind all these are why non-energy, industrial commodity prices, including copper, have tanked, too, even though, especially copper (see: Chile strikes), supply fundamentals remain overwhelmingly price-positive.

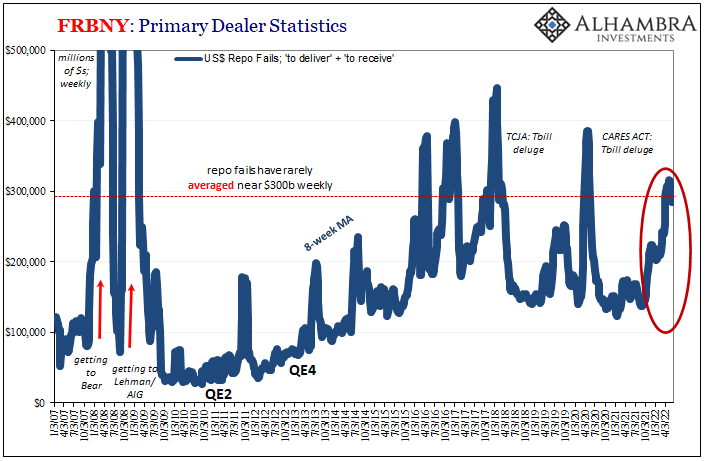

It’s everywhere; demand globally has been destroyed to the point that what all the data is saying is the same thing. In terms of these PMIs, they are now catching up to where markets had priced probabilities months ago. With markets pricing even worse probabilities now (see: eurodollar futures), you can see where everything is headed.

No longer “if”, not even much of a question for “when”, we’re on to “how bad” – across-the-board, finance as well as global economy.

Stay In Touch