The FOMC met last week and did what everyone expected them to do – raised the Fed Funds rate by 0.75%. The bond and stock markets reacted not to this action but to the commentary provided by the committee in its statement and by Chairman Jerome Powell at his post meeting press conference. The former had a new phrase, a change from the statement after the last meeting:

The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time. In determining the pace of future increases in the target range, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.

The markets took that to mean that the pace of future rate hikes may slow, that the FOMC doesn’t intend to keep hiking 75 basis points in perpetuity but may step that down to 50 basis points or maybe even 25. Not exactly shocking if you ask me but stocks rallied on that statement, the Dow up 400 points just before Mr. Powell took the stage and sent the market down 900 points. How? Frankly, I read the statement and watched the entire press conference and I can’t tell you. He didn’t say anything that was significantly different than the statement.

He did speculate that slowing the rate hikes might, in the end, mean that rates go higher but he doesn’t know that and with the Fed’s forecasting track record, I don’t know why anyone would take it seriously. So, did the market just end up where it would have been if Powell and the FOMC had said nothing at all? That is, after all, what used to happen after an FOMC meeting. For years, the committee would meet, do something – or nothing – sending instructions to the NY Fed to execute the necessary transactions – or not – and adjourn until the next meeting. No one knew what they had really done until the open market desk started executing trades…or not.

Today, everyone knows what the Fed is going to do, or at least very close. We all knew the Fed would hike rates by 75 basis points and that’s what they did. The attention to the statement and Powell’s press conference is so intense because traders, investors, and computer programs are all trying to figure out what they’ll do next in the hopes that such knowledge will allow them some advantage in the market. Markets move based not on what is happening or likely to happen in the economy but on how changes in the economy will be interpreted by the 12 members of the FOMC. Their favored economic theories, their models of the economy, have become more important than the economy itself.

We have entered some 3rd dimension of Keynes’ beauty contest where we’re trying to figure out how traders will react to how the FOMC reacts to how their models react to economic and market information that has been distorted by previous actions of traders reacting to the FOMC.

I wrote last week about the inversion of the 10-year/3-month yield spread and the potential meaning of such a change. It has been a reliable indicator of recession in the past and we – and everyone else on the planet – watch it. Here’s what I didn’t tell you. The 10-year/3-month Treasury yield spread can be calculated using more than one set of data. You can use the constant maturity version of each security which is what you get if you go to the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s FRED site and is an interpolation produced by the Treasury on a daily basis. Or you can use actual on-the-run securities. Or you can use the indexes constructed by various entities. Just to make things more complicated, these things don’t always agree.

Does it really matter? What if one of these produces a curve that stops flattening at 2 basis points and another one inverts by 2 basis points? Has the curve inverted or not? If not, does that mean we’ll avoid recession? If so, does it mean one is assured? That’s ridiculous, isn’t it? A difference of 2 basis points determines whether we get recession or not? Yes, it is absurd, but if you put that out for discussion you’d get people digging in their heels on each side, one certain we’re headed for recession, the other just as certain that we aren’t.

That doesn’t even consider how the curve today might be different than it was in an earlier era. Does a yield curve inversion in March 1973 mean the same thing as a yield curve inversion in 2022? And by the way, there is no evidence that an inverted yield curve causes a recession; all the popular explanations – banks won’t lend with an inverted curve – aren’t supported by the data.

Would the curve be inverted now if the Fed still had the same communication policy it did under Greenspan? What about under the intimidating Volcker and his cloud of cigar smoke? Or Arthur Burns or Marriner Eccles or Bill Martin? What about the monetary system? Does the inverted yield curve mean the same thing today as it did when a much larger part of the economy was funded through the banking system? How is the curve different today with gold playing essentially no role in monetary affairs? How is it different in a floating exchange rate system versus one, like Bretton Woods, with fixed exchange rates?

The dissemination of information today is instantaneous and everyone has access. It isn’t just economic data but speeches by Fed governors and FOMC statements and press conferences and SEPs (summary of economic projections). With everyone aware of the Fed’s intent – forward guidance – do traders and investors front run the Fed, raising short-term rates faster and farther today than they would have in an earlier era? If the answer to that is yes – and I’m pretty sure it is – then how do we factor that into our timeline to recession?

I hear investors today speak as if this macro stuff is easy, as if there is a set game plan that you follow after certain things, like a yield curve inversion, happen. Uh-oh, the yield curve inverted so I should sell stocks, buy longer-duration bonds, wait for the recession to pass, and then reverse everything. Except it isn’t that simple is it? The 10-year/2-year yield spread inverted 7 months ago to a chorus of bears calling for imminent recession and we’re still waiting. Yes, stocks are down from the initial inversion to today, but the drawdown is pretty mild outside of the large-cap growth stocks.

Since April 1st (when that curve first inverted), the S&P 500 Value Index (IVE, Alhambra owns) is down just 8%, the Select Dividend Index (DVY, Alhambra owns) is down 6.2% while the growth index (IVW, Alhambra does not own) is down 24.3%. You didn’t need good market timing to outperform in this case; you just needed to recognize that growth stocks were grossly overvalued. Furthermore, the curve didn’t really invert for good until July 6th and since then IVE and DVY are both up while IVW is again down. I could be wrong but I don’t think that has anything to do with any potential recession.

The selling in stocks started well before the yield curve inversion though, because with everyone knowing about the yield curve as a recession indicator, you have to sell early to gain an advantage. You have to sell before the next guy who has the same knowledge you do and the next guy and the next guys who all know the same thing you do, that the yield curve is inverting and a recession is coming. And so stocks sell off not only well before the recession but even before the recession indicator sends up a warning flag.

Selling stocks early in this case appears to have paid off but if you didn’t sell your bonds too, you’re still hurting. And if you went out and bought some long-term bonds in anticipation of a recession that hasn’t arrived yet, you could actually be losing more than if you’d stayed in stocks. To quote the most important Buffett (that would be Jimmy) in his seminal work, God’s Own Drunk, “it’s so simple, like the bugaloo it plum evaded me”.

Macroeconomic information is useful for investors but it isn’t the cure-all everyone wants it to be. It isn’t as simple as memorizing a few rules. It requires thought, an open mind, and above all, a lot of humility. Don’t put your faith in any one indicator; you’ll surely be disappointed. What happened in the past doesn’t have to happen in the future and the more people are aware of the past, the less likely we are to repeat it. And just because something has never happened doesn’t mean it won’t in the future.

A very smart man once told me I shouldn’t worry about the things that everyone else is worried about. Things that are “well worried” are already in the market price. The yield curve (as if there were just one) is inverted. I know that because my waiter told me about it the other night at dinner.

Environment

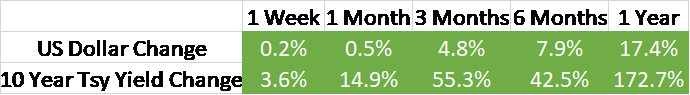

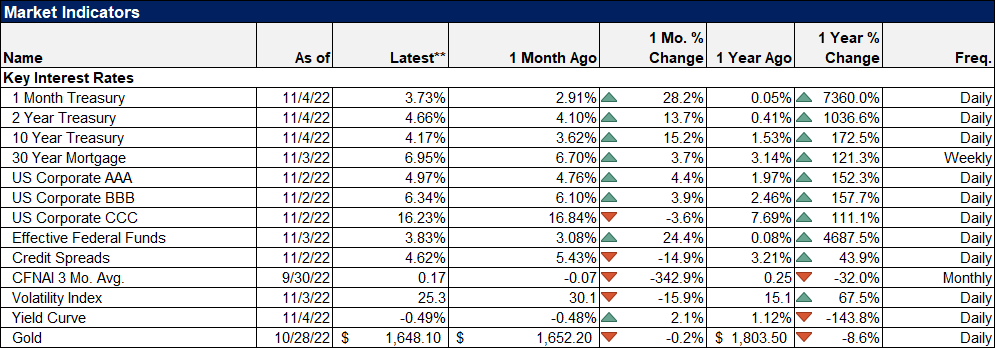

The trend for the dollar and the 10-year Treasury yield is still up but, as I said last week, both appear to be hitting a short-term peak. It could be a long-term peak for all I know but let’s just say that, despite the Fed’s hike last week, both are struggling to maintain upward momentum.

Both the dollar and rates spiked higher in the wake of the latest FOMC meeting last Wednesday. Neither, however, was able to make new highs for this uptrend. The dollar’s fall Friday was truly stunning (-1.8% for a daily move in FX is huge) and should remove any doubt about the source of the dollar’s recent strength. Currencies move on changes in relative growth expectations. Last week, the market decided that the outlook for the rest of the world improved – a lot – relative to the US.

More specifically, the rumor/speculation that China would end its zero COVID policy early next year seems to have been the driver of all markets in the two days after the FOMC meeting. I would also point to the joint statement of Olaf Schulz and Xi Jinpeng about the use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine as a potential cause. Anything that reduces geopolitical anxiety is going to be dollar negative. On the other hand, the Chinese have not confirmed yet that the end of Zero COVID is in sight so this may be very short-lived.

And remember the trend for rates and the dollar is still up. It isn’t just nominal rates either; the 10-year TIPS yield hit a 13-year high last week. What does that mean? It means real growth expectations are rising and inflation expectations are falling. A rising dollar, rising growth expectations, and falling inflation expectations have, in the past, been positive for stocks. Not exactly a consensus opinion right now but that is what that environment has produced in the past. Will it last? I have no idea; maybe the China re-opening rumor is false. Or maybe it isn’t. We are, once again, foiled by the lack of a working crystal ball.

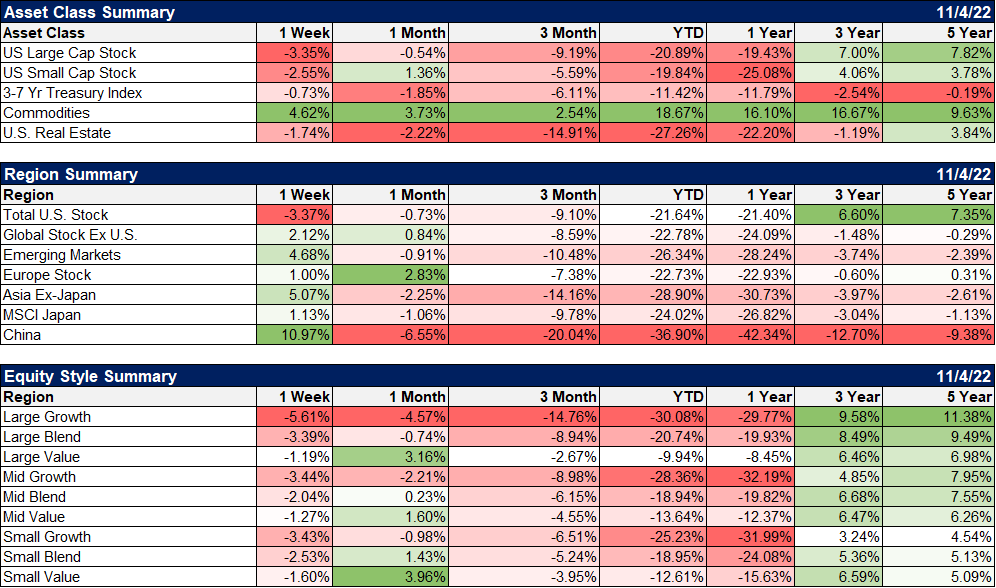

Markets

US stocks were down last week but non-US stocks had a great week. The selloff in the dollar Friday goosed non-dollar returns by nearly 2%; the Eurozone ETF (EZU) rose 5.3% on Friday alone while China ETFs were up over 7%. We own an international value ETF (EFV) and an actively managed international value fund which were up about 4% Friday and finished the week higher by about 2%. International value has outperformed the S&P 500 this year by about 4% which is amazing when you consider the drag of the stronger dollar.

Commodities and gold were both up last week helping our diversified portfolios. Despite the down week for most US stocks and bonds, our portfolios managed to stay basically flat. Some accounts were up a fraction, some down a fraction depending on risk tolerance. The 60/40 portfolio we track (60% Vanguard Total Stocks, 40% Vanguard Total Bond), was down 1.8% last week. Diversification really is the only free lunch on Wall Street.

Value continued its outperformance last week and the trend is accelerating. Large-cap value is now down just 7.7% (including dividends) on the year and has outperformed growth by over 20%. And there is a lot more room for that to continue. These trends tend to last quite a long time. LC growth outperformed LC value for roughly 15 years before this year’s reversal. BTW, dividend stocks resumed their outperformance last week as well, down just a fraction of a percent.

Another emerging trend we’ve been watching is small cap vs large cap. Small cap stocks have outperformed recently but large cap has outperformed for most of the last 10 years. We are watching this closely though because, like value stocks, small-cap stocks tend to outperform in falling dollar environments. We aren’t there yet obviously but value may be signaling a change. If it does, we would expect small and mid-caps to outperform. We would also note that small and mid-cap stocks are considerably cheaper than their large-cap cousins. The S&P 600, Russell 2000, and S&P 400 trade for 0.8, 1, and 1.1 times sales versus 2 times sales for the S&P 500 (and 3.2 times for growth stocks).

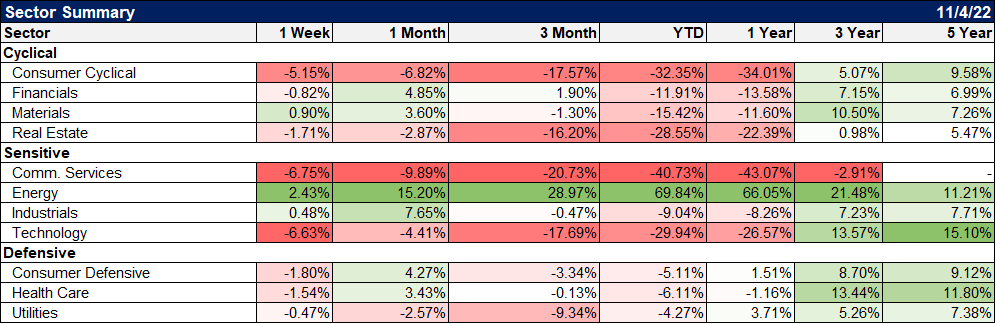

Energy, materials, and industrials were the winners last week while technology continued to get its clock cleaned. The winners are all areas that would benefit from a China re-opening and a global growth revival. I have some doubts about the China re-opening theme though and would be wary of chasing it. Even if they do decide to modify or abandon the zero-COVID policy, it seems unlikely to happen until after the winter. One interesting development last week was China’s approval of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for foreign residents in the country. Is that a precursor to a wider approval of the vaccine? (Disclosure: Alhambra and its clients own both Pfizer and BioNTech equity). If so, opening could be sooner than expected.

Investing cannot be reduced to a set of formulas. If it could, someone much smarter than you or I would have done so already. And as soon as it became known, it would be useless. Investors would try to gain an advantage by anticipating the formula and in doing so would change the economy and markets in unpredictable ways. I don’t know if that has happened with the yield curve or any of the other indicators we follow. But I would be derelict in my duties if I didn’t consider the possibility.

I am also reluctant to compare today to any period in the past because of the unique nature of the pandemic and the response to it. I expect economists will study this period – and the post-GFC QE period that preceded it – for generations, as they have the Great Depression. I also expect they will be arguing about it – as they still are the 1930s – nearly a century from now.

Economics and investing are more art than science and more Pollock or Miro or Kandinsky than Cezanne or Van Gogh or Michelangelo. The market is an abstract, not a still life. You can’t just assume that the old rules still apply, that nothing has changed or ever will. You have to expect surprises, changes, positive and negative, and deal with them as they arise. The art of investing lies in realizing that the canvas of the market is ever-changing, perspectives shifting as ideas and information are absorbed into the common knowledge that we call “the market”. It’s always different this time to some degree.

The Swan, No. 3, Hilma af Klint

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch