Over the weekend, Charles Schwab issued a “tool” for investment advisors to help them “feel good” about what is expected for 2016. With investors increasingly talking about risk, and stock market risk at that, there is a counter-rush to reassure. Some of that is expected in places like this, but increasingly the disparity between the form of that encouragement and the wider awakening ends up on different planets.

Jeffrey Kleintop, chief global investment strategist and senior vice president at Charles Schwab, believes that there are good reasons to be positive about the future: Global economic data is generally exceeding expectations, and most forecasters expect 2016 to post the best global economic growth in years. He believes stock market investors can achieve positive rates of return and lower their downside risk, but they may be unlikely to act unless they can renew a sense of optimism and HOPE.

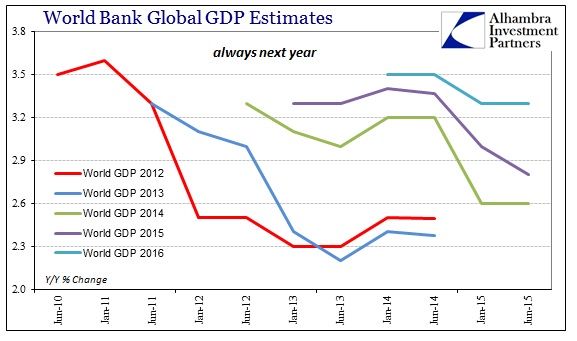

It is an exceedingly odd paragraph all around; contradictory in how it frames the global economy, touched with rainbows and unicorns about how you can “achieve positive results and lower…downside risk.” The second part obviously suggests what Schwab is seeing from its retail client business, as, again, investor uncertainty is starting to be unusual in a radical departure from the prior few QE-strewn years. However, the first part, “best global economic growth in years” is a touch disingenuous since the same was said about 2015 in late 2014 (and about 2014 in late 2015, etc.).

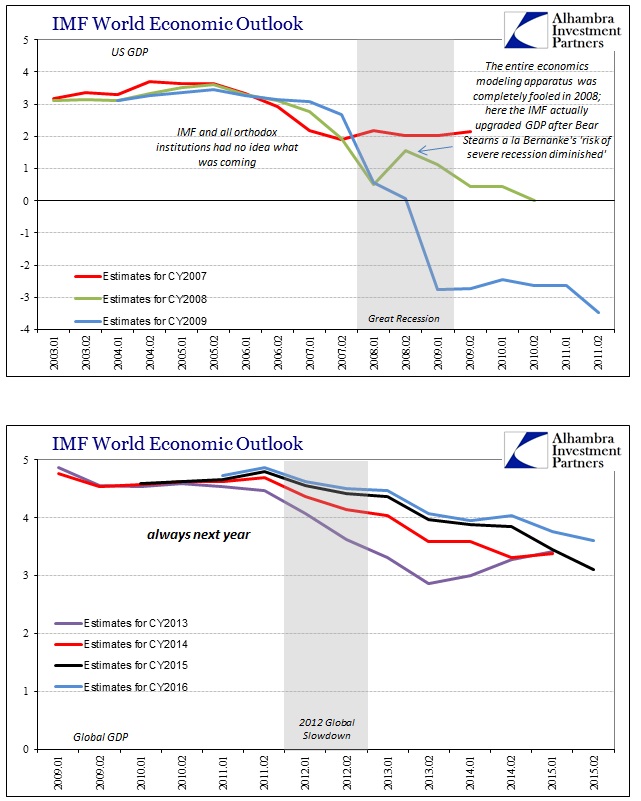

Furthermore, there is already a rush to downgrade next year by “most forecasters” including and especially mainstream, orthodox outfits like the IMF and World Bank – the very sorts of places that are normally cheering the way forward. The IMF in its latest October outlook sounds nothing like its unequivocally awesome reassurances from less than two years ago. First, October 2015:

“Six years after the world economy emerged from its broadest and deepest postwar recession, the holy grail of robust and synchronized global expansion remains elusive,” said Maurice Obstfeld, the IMF Economic Counsellor and Director of the Research Department.

“Despite considerable differences in country-specific outlooks, the new forecasts mark down expected near-term growth marginally but nearly across the board. Moreover, downside risks to the world economy appear more pronounced than they did just a few months ago,” Obstfeld said.

Compared to January 2014:

The report describes a global economy that is at a turning point. For the first time in five years, there are indications that a self-sustaining recovery has begun among high-income countries – suggesting that they may now join developing countries as a second engine of growth in the global economy.

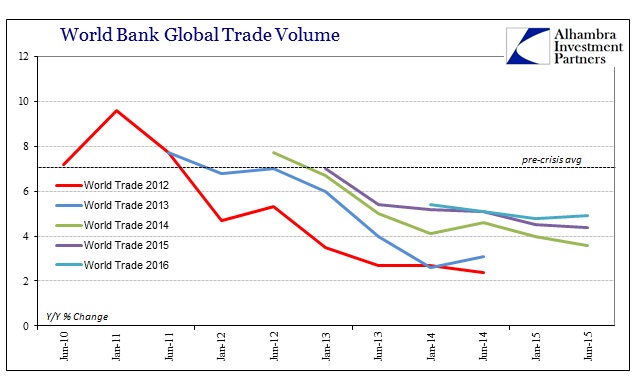

The stronger growth in high-income countries reflects progress in both private- and public-sector healing in the wake of the financial crisis. In particular, the drag from fiscal consolidation and policy uncertainty is expected to ease sharply in the United States and in high-income Europe. The stronger growth in rich countries is expected to boost demand for the exports of developing countries and contribute to a modest acceleration in their growth. Overall, global trade growth which has been particularly weak is expected to strengthen over next few years reaching about 5.1 percent by 2016.

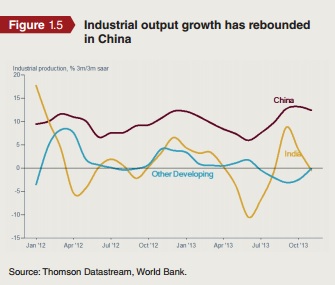

“Something” has changed since then, including how far off the IMF was in emerging markets. Rather than being a “second engine of growth”, EM economies have turned into flat out nightmares. The IMF in its January 2014 report even went so far as to highlight how Chinese industrial production had turned the corner.

It was the same mistake that everyone seemed to make, assuming that EM’s were about to return to their pre-crisis, high-growth state. Nobody saw the “dollar” coming even though it had rumbled strongly in the middle of 2013; just enough for the mainstream to marvel in curiosity before dismissing it and moving right into Bernanke’s (now Yellen’s) recovery that just never seems to actually show up beyond the unemployment rate. Among those completely unprepared for 2015’s EM meltdown was Charles Schwab and Jeffrey Kleintop:

Supported by slightly stronger global economic growth, central bank stimulus and supportive fiscal policy, Kleintop expects global stocks to rise again in 2015. He is particularly bullish on emerging market stocks due to attractive valuations, and anticipates they will outperform developed international stocks.

I don’t mean to be overly focused on Schwab and Mr. Kleintop, only that I think it demonstrates the top-down problem with the anti-scientific nature of economics as it is currently. The discipline holds onto the recovery idea first and foremost which is nothing more than modeled assumptions – the ephemeral, rather non-specific and always positive “global economic growth.” Econometric regressions just assume monetary policy works, full stop. Thus, if a central bank does something it already pushes up “next year’s” growth forecast; if a central bank does a lot, there can be no denying it in the math. So the math is “more real” than what we see now, because it is so determined about what is going to happen that whatever actually happens now cannot be important – it must be anomalous or transitory.

The story of 2013 was a high-grade warning that the financial system was not only far from resilient and normalized, it was starting to become dangerous again. But QE was on its fourth, so that just couldn’t be the case.

For Schwab’s trajectory, it is only slightly behind the IMF’s and the World Bank’s. In early 2014, there was clear sailing everywhere and “next year’s” recovery undoubtedly assured. Not too far into 2015, EM’s were dead but that didn’t mean revisiting anything other than how “next year’s” economy was distributed. EM’s suddenly weren’t all that important to anything other than EM’s, so generous growth remained still the base case but perhaps only more uneven than thought. Very few seem to contemplate what might have happened that would alter the universal panacea of global growth between then and now, preferring instead the view that the world took its stimulus and moved nowhere but forward.

Those that do often come up with nothing. If the economy is suffering or off track it is only because it is; it is the standard tautology of the ideologically committed, the recovery is substandard because the recovery is substandard. This was most recently deployed in Japan where after massive and unprecedented QQE, criticism of the Bank of Japan is, in light of renewed recession, that they didn’t do enough. It strains general and basic logic, that despite the most “powerful” and massive “stimulus” ever conceived and unleashed the economy has gone only backward – and thus it is the fault of the economy?

Those calling for even more inflation are “vindicated” because Japan’s economy has gotten worse? It’s as if all prior QE’s, and there were almost too many to count (though I have tried, below), never happened. The current recession in Japan, which is picking up in its depressive tendencies, is just assumed to have come up out of nowhere like Godzilla arising from the underworld.

Over the weekend, President Obama gave an interview with NPR that was full of this “it’s bad because it’s bad” kind of myopia. I don’t mean to turn this political, as the shoe was squarely fixed on the other party foot in 2008 as Republicans of all kinds rushed to downplay the economic events of the Great Recession as it was unfolding, but who has been President for nearly seven years during all this? Obviously, government has a limited economic role, but that isn’t how these people see it (again, including R’s). Like central banks, they claim and promise all sorts of economic solutions and now are again trying to say, “the economy is bad because the economy is bad” as if they never did anything about it.

But I do think that when you combine that demographic change with all the economic stresses that people have been going through because of the financial crisis, because of technology, because of globalization, the fact that wages and incomes have been flatlining for some time, and that particularly blue-collar men have had a lot of trouble in this new economy, where they are no longer getting the same bargain that they got when they were going to a factory and able to support their families on a single paycheck, you combine those things and it means that there is going to be potential anger, frustration, fear. Some of it justified but just misdirected.

The President used that statement to “explain” how he sees Donald Trump’s campaign success so far; and I think that is absolutely true. The people, Main Street as they are always referred to, have had enough with not just the promises for success but the lack of explanation for why it hasn’t happened. They are increasingly fed up that when things start to get worse, not only will central banks and all the “fiscal stimulus” just ignore that none of it worked before (how could it “work” if things never improved and now are looking uncertain yet again) it is done so with nary reality attached to it – “it’s not getting bad, it’s just less good than we thought.” The arrows are always pointing up, just not for today.

To admit that there is no stimulus in “stimulus” puts central banks and orthodox economists out of business. There is no more deeper explanation than that; secular stagnation is really CYA. The problem with claiming all sorts of miracles about monetarism and central banking, including asset prices, is that it has to work at some point – there is a pre-determined expiration for all of it. Far enough along, it either works as advertised or it loses all power through persuasion, including the math. The politics of this year and the increasingly detached commentary trying to describe all of it (“China’s no big deal except to China”) suggest that endpoint might finally be rounding into view.

If that turns out to be the case, how it is accepted and reformed will determine whether or not we turn Japanese, or just lose one decade to centralized ineptitude.

Stay In Touch