Stimulus always works because every uptick and improvement is attributed to it no matter how small and ultimately inconsequential. That has been the history of the past four years now, as the slowdown has not come at a steady pace. Nothing goes in a straight line except mainstream extrapolations of every positive variation. And when whatever indication is lower and conforming to trend, that just means more stimulus will be forthcoming. Stimulus can never lose, unlike the actual economy.

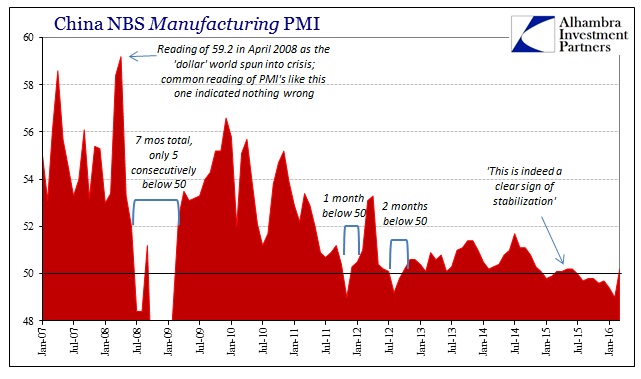

The first look at March through PMI’s has returned the positive variations as well as the “it’s over” declarations. China’s official manufacturing PMI broke back above 50 for the first time since last July, which in the mainstream means growth (which is further extrapolated into stimulus-led sustainable recovery based on only one month). A more consistent interpretation of what PMI’s actually suggest is only that March might not have been as bad as January and February, a far different perspective especially since the first two months of the year were downright horrific.

China’s official factory gauge showed improving conditions for the first time in eight months, suggesting government’s fiscal and monetary stimulus is kicking in. The manufacturing purchase managers index rose to 50.2 in March, compared with a median estimate of 49.4 in a Bloomberg News survey of economists. The measure matches its highest level since November 2014.

That last part, at least, is accurate as the PMI had indeed previously matched that “highest level since November 2014” in the middle of last year, which featured then the exact same rhetoric.

A Chinese manufacturing gauge for April suggested that growth may be starting to stabilize in the nation’s economy after the government spurred infrastructure investment and eased monetary policy…

“This is indeed a signal of stabilization,” said Zhu Qibing, an economist at China Minzu Securities Co. in Beijing. Zhu said electricity consumption and industrial product prices that he tracks showed a pickup in the second half of April.

The reason for suggesting “stabilization” almost a year ago? Stimulus:

Policy makers cut interest rates and reduced banks’ reserve requirement ratios twice in the past six months to prevent a deeper slowdown. China’s Communist Party leaders vowed in a meeting Thursday to step up targeted controls to counter downward pressure on the economy.

It didn’t work then, and hasn’t worked for years, but in these positive variations it is all that matters as one month becomes the sole and guiding focus. And if the PMI falls back below 50 again next month, that’s just more good news because it will mean that more “stimulus” is on the way. Stimulus is only fantastic; it either works or is about to get bigger and expanded.

This narrative is formed around all of the economic accounts, especially in China where the mainstream seems to really want “stimulus” to have its effects, as if the whole of orthodox theory were riding on the outcome. Perhaps that is true since there is a great deal about China that actually disproves not just idiosyncratic applications of monetarism but really the whole global fashion. Thus, the sustained direction is not the one hoped for since all Chinese data continues to be stuck in worsening circumstances after years of the seesaw between “stimulus works” and “more stimulus is coming.”

This disparity in interpretation is all the worse where PMI’s are concerned because the 50 or not 50 shorthand is taken literally; as if 50 actually means growth and less than 50 not growth. Further, whether or not a PMI is above or below 50 doesn’t actually tell us much about what to expect next month or the months immediately thereafter. China’s manufacturing PMI was 59.2 in April 2008, fell sharply to below 50 that July and August before rebounding, like now, to 51.2 in September 2008. That last jump above 50 was meaningless except insofar as I suggested above, that late summer 2008 might not have been as bad in China as early summer 2008; there wasn’t the slightest hint, despite being above 50 again, that there had been a wholesale inflection in Chinese economic fortunes. Instead it was the comparison to the levels that existed before that suggested where China’s economy was heading.

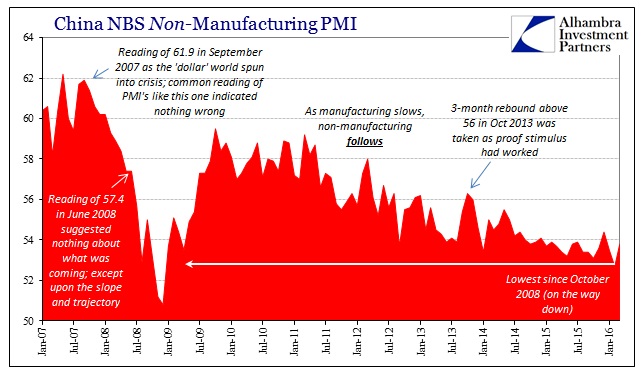

That is perhaps almost perfectly clear in the non-manufacturing PMI, which has been decelerating for years in just this sort of jagged, saw tooth fashion. The PMI surged in the latter half of 2013 which was believed then that 2012’s massive “stimulus” had worked and that it would portend nothing but good things from there on; it didn’t. Thus, what is relevant is not how March 2016’s 53.8 compares to February 2016’s 52.7, but rather how 53.8 this March means only one direction in view of 54.5 in March 2014, 55.6 in March 2013, and 58.0 in March 2012. In other words, no matter the monthly variation China’s PMI’s suggest much, much closer to China-style recession than what “stimulus” is supposed to provide.

Unlike the sharp second derivatives in 2008, the trajectory remains on the much shallower slope into 2016 and still appears to be the same slowdown that just doesn’t stop slowing. It just doesn’t do it all at once or in a straight line, but it’s still a worsening set of economic circumstances for China and direct reflection of the global economy.

Stay In Touch