They put it off so long they backed themselves into this corner. The Japanese government under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had originally scheduled two VAT tax hikes as part of the rollout for Abenomics. It would be inflationary and fiscally responsible all in one pass. To make sure Japan’s perpetually struggling economy could absorb any fallout from them while still moving forward there would be “stimulus” just to make sure.

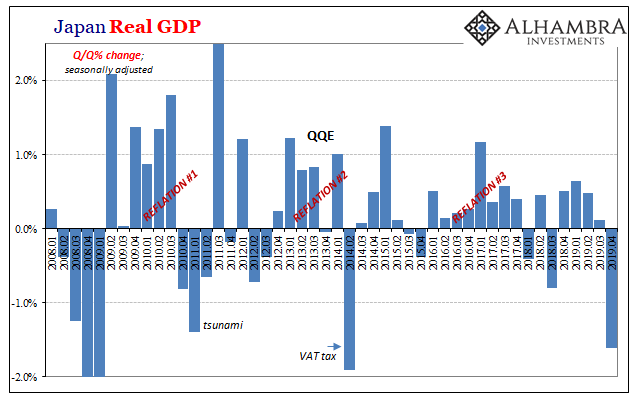

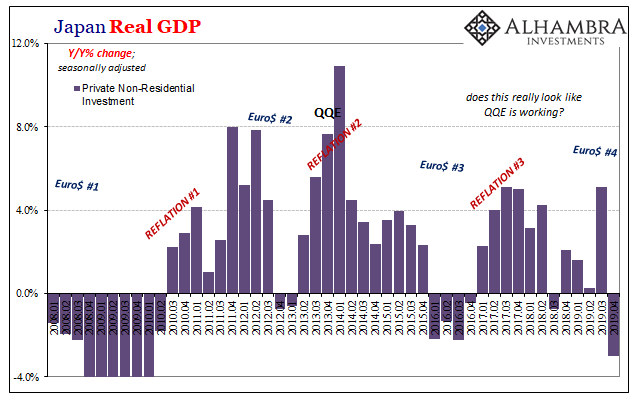

The first tax hike took place as scheduled in April 2014. QQE was working if not working really well, it was widely believed. By October 2014, however, the Bank of Japan under Haruhiko Kuroda, Abe’s monetary wingman, was sufficiently worried that QQE was actually enlarged. The second tax hike loomed for the following year.

Never happened. Euro$ #3 foiled all plans, including the most “powerful” monetary stimulus money printing ever conceived. The VAT change was postponed once and then once more as the dark clouds of international weakness just wouldn’t clear up.

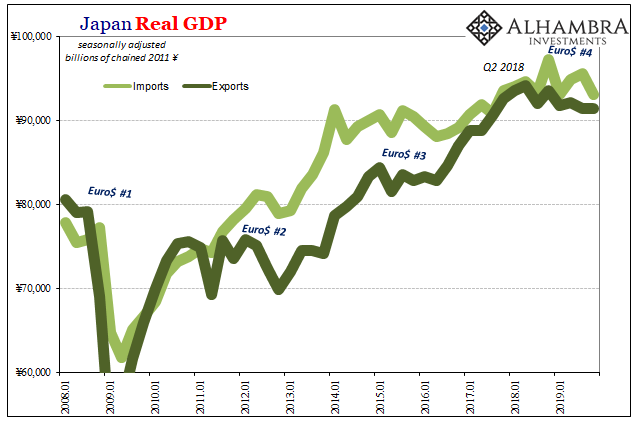

By early 2018, however, officials in Japan as well as everywhere else deluded themselves into believing they finally had.

Kuroda started talking about ending QQE and Abe finally felt the economy solid enough to move forward with that second VAT adjustment. It was rescheduled for October 2019, this time forrealsies.

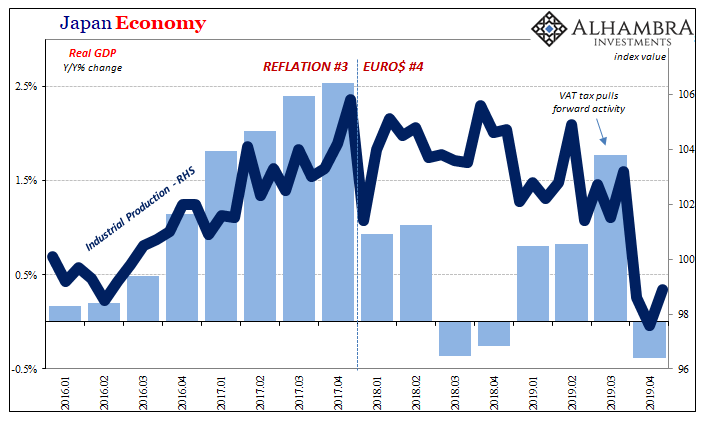

And just as it was the global economy turned sour (again). In the second half of 2018, Japan’s economy lurched toward technical recession (year-over-year, GDP contracted in both Q3 and Q4 2018). The Bank of Japan stopped hinting at QQE’s end date.

The government, on the other hand, by their own actions and promises had been left no choice. At the beginning of the fiscal year last March, ¥2.03 trillion in fiscal “stimulus” was granted to shore up any nagging economic worries or tendencies. The Prime Minister told the budget committee of the lower house of Japan’s Parliament that, “I want to create economic conditions conducive to a consumption tax hike.”

By the midyear, some were wondering if he had. The economy had picked up modestly from its 2018 slump, avoiding the dreaded cyclical declaration. GDP growth turned positive if nothing special, stoking the usual predictions of a confident acceleration among some, particularly those working for the government.

Uncertainty continued to swirl but Abe declared in July the consumption tax was going to happen “unless something on par with the global financial crisis triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers takes place.” There was no second Lehman, so the Japanese people were taxed on October 1.

As a consequence, everyone knew that growth would be a little higher in Q3 2019 than what nowadays counts as normal and then a little lower in Q4. The Japanese public would purchase as much as possible in September before the new rate could be applied.

When the stats for household spending came out for September, however, it showed a record surge. Rather than being indicative of strength, it was an ill omen much like it had been in 2014. If Japanese consumers were that motivated to save a few percentage points in taxes, it did not portray consumer confidence nor portend strength.

Japan’s Cabinet Office has now updated its real GDP estimates for Q4. They are much worse than what had been expected. Consensus (FWIW) had thought GDP would shrink by about 3.5% quarter-over-quarter (annual rate), instead the decline was nearly twice that. At an annual rate of -6.3% (-1.61% quarterly rate), it was the economy’s worst showing since the last time the tax rate was raised.

But this time was supposed to have been different. It’s turning out to be exactly the same, though, and not just when it comes to the tax drama. More than anything, what’s haven’t changed are these global disinflationary pressures which began blowing into Japan’s trading ports at the same time they showed up everywhere else around the world.

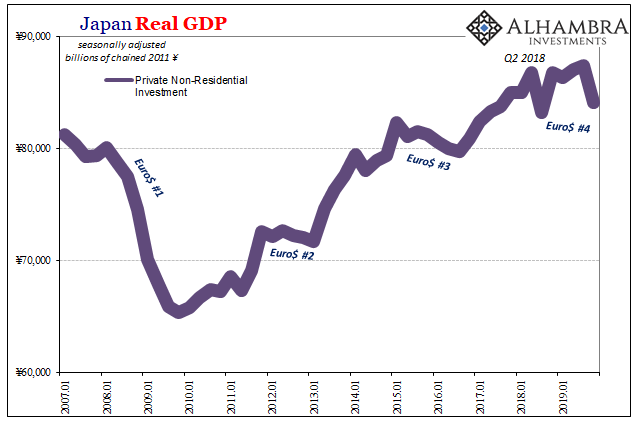

While early on in 2018 Abe and Kuroda were saluting what they saw as the long-delayed positive effects of Abenomics, the Japanese economy was already being undermined; it was already heading toward the downturn. I don’t know how much clearer it can possible be (above), cause and effect.

The VAT levy is surely cause for some of the negative in Q4, but not this much. Within the GDP accounts there are any number of further warning signs (many of the same as there were in Q4 2019 US GDP estimates) well beyond consumer spending and taxes. Private Consumption (excluding rent and shelter) may have declined at a 3.7% annual rate, but so did Private Non-residential Investment (capex).

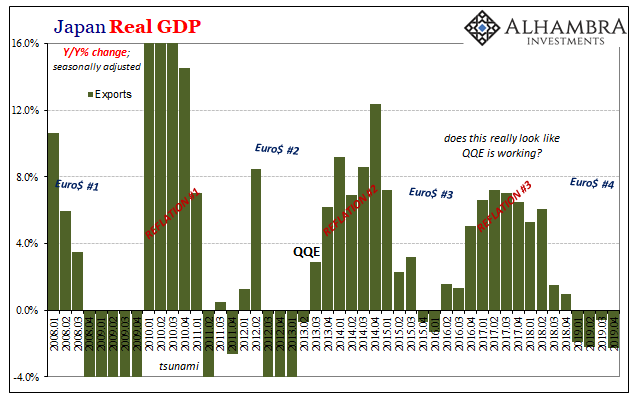

The latter has little to do with Japan’s fiscal situation and much more to do with those marginal changes in the global economy – synchronized downturn. Exports were down in all four quarters of last year, including the final one with all its trade deals and improved sentiment.

Japanese authorities like their European and American counterparts have taken notice of global headwinds and disinflationary pressures but still don’t seem to know much about them. If they had figured some of this out, they wouldn’t have committed those mistakes in 2018 making the molehill of Reflation #3 into their Mountain of Awesome (with its widespread, even Japanese, inflationary hysteria).

They wouldn’t have just dismissed Euro$ #4, the disinflationary pressures all the way back then.

More recently, officials wouldn’t have become so positive and confident about the latter months of 2019, either. Though it has been claimed (over and over) that last year ended well, the evidence continues to pile up that it didn’t. It so didn’t.

In Japan, at least, there were taxes to blame; unfortunately, not nearly to this extent. You can definitely add the Japanese economy to the growing list of warning signs. The economic effects (headwinds) of the disinflationary pressures seem to have been even stronger in Q4.

It seems yet again that the widespread rumors of Euro$ #4’s demise have been greatly exaggerated. They talk openly about disinflation now, so you’d think they’d take some time to truly understand what’s behind them. Apparently, that’s just asking too much; hits a little too close to home – for central bankers, at least.

Stay In Touch