Part 1 is here.

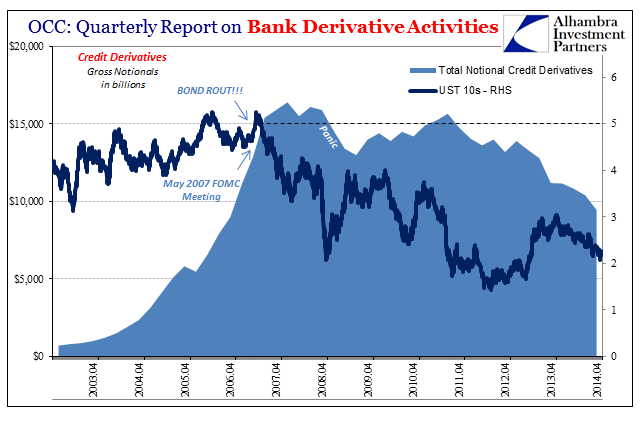

The real clue as to what was going on monetarily was provided in early 2008 not by a Federal Reserve statement about some new program it was hastily putting together (except by proxy of what it meant for conditions in private wholesale markets that the Fed thought it necessary to hurriedly arrange some new liquidity program, of which there were several). It was instead given to us by AIG deep within the notes of its 2007 annual report.

Approximately $379 billion of the $527 billion in notional exposure on AIGFP’s super senior credit default swap portfolio as of December 31, 2007 were written to facilitate regulatory capital relief for financial institutions primarily in Europe.

There are two vitally important terms contained within that short passage. The first is “primarily in Europe”, suggesting why it was that the ECB made first contact with the Fed for dollar swaps all the way back in 2007. Its banks were at the center of all this, though to be proper we need to specify that banks located within Europe were not necessarily European. By that I mean their business was global, and therefore “dollar” rather than strictly euro.

For monetary policy, the issue was to whom these banks belonged. They were a huge part of the global dollar, yet they were European (or Japanese). The Fed’s bureaucratic interests placed exclusive emphasis on geography, not the whole currency system (meaning what it was and is these offshore entities did with and among each other all in the name of dollars). Thus, the US central bank chose instead swaps with other central banks like the ECB so that those other central banks would be responsible for their own.

It was a colossal mistake; seeing institutions by national definitions had the effect of obscuring vital dimensions. The dollar, or “dollar”, was broken, not specific banks in Europe or America.

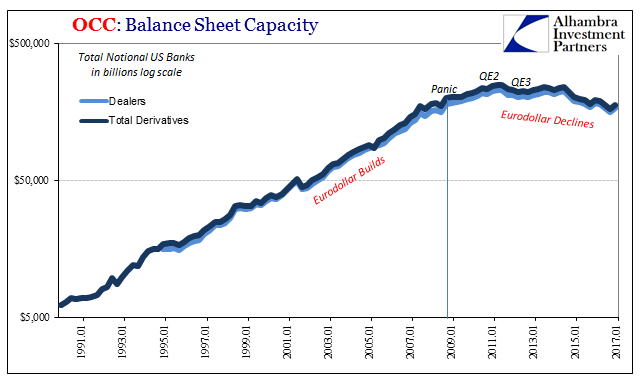

The second phrase is everything about the mature eurodollar system, largely because it shows us with specificity what that system had become – balance sheet capacity that was traded and provided by outside parties and every bit liquidity as whatever else was on the liability side. The idea of “regulatory capital relief” isn’t particularly dense, though it may seem that way especially attached to the practice of credit default swaps (or interest rate swaps, etc.).

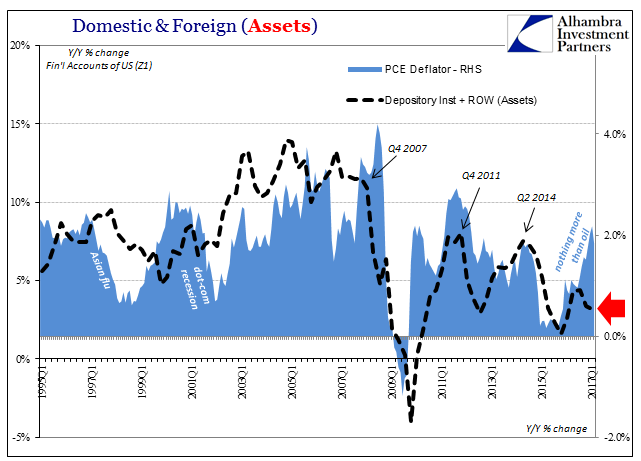

What the Fed wished to swap could not come even close to replacing what banks had been getting swapped from the rest of the private system. What follows in only one of those dimensions, a very important one.

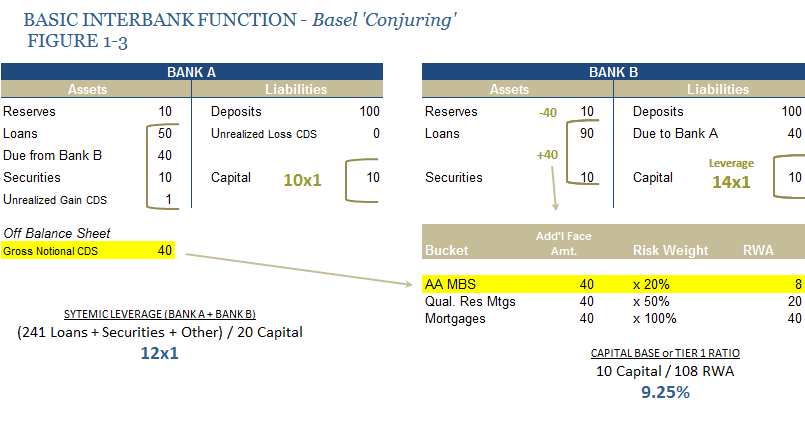

The goal of any financial institution has always been to expand its activities as far as it possibly can. In days long gone, that meant deposits of actual money sitting in one form or another in its vaults (money multiplier). In the latter 20th century, it came to mean something very different. Multipliers still exist, but they have evolved and have been formalized. The concept of Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA), or other balance sheet parameters (I won’t get into them today), is really that leverage in another form (regulatory capital relief).

The Basel rules governed the way in which capital ratios were achieved. They allowed for this sort of accounting, meaning that when first adopted it was thought that any bank holding a risky asset should not be penalized with a reduced capital ratio if it was to pair that risky asset with some sort of guarantee. Originally conceived as a GSE contract for a mortgage bond, the definition of what qualified in this sense was slowly (and greatly) expanded over the decades.

The goal is simple enough and even sympathetic; a bank that holds $100 in US Treasury bonds for $8 in capital is not at all as risky as another bank holding $100 in subprime mortgages with the same $8 in capital. Yet, the simple capital ratio declares that they are (8% in each case).

The Basel rules devised a bucket approach so as to allow for these kinds of distinctions. Sovereign bonds are given a zero weighting, which means you can hold however much you may wish and be called fully reserved (capital wise). For a bank, then, the trick is to see how much you can make subprime mortgages appear like US Treasuries in order to receive similar treatment. You can never get an MBS all the way down to a zero weighting, but you can get close. All definitions of risk drill down to credit, never much accounting for liquidity.

Buying what is essentially portfolio insurance is that method, even if it is in the form of credit default swaps written not by a depository institution with monetary recourse to the Federal Reserve but an insurance company like AIG.

Note: the above graphics are from my upcoming Eurodollar University series with MacroVoices, the first part of which will be aired this week. I go into more detail about this kind of balance sheet leverage in that production.

In the example above, Bank B, which was in reality very likely a European bank, had contracted with Bank A, very likely AIG, an insurance company, or money dealer like it, to engage in Basel trickery. It can turn what would have been an asset with perhaps a 100% risk weighting into one as low as 20% (the exact way in which it does, or did, is determined by accounting tests and rules). The effect on Bank A’s capital ratios can be enormous (which is why there are so many derivatives, and why it came to be that way during the 1990’s and 2000’s).

The additional $40 in securities (MBS) shown above would have been added at $40 RWA without the CDS applied; with it, I have put it simply in the 20% bucket (this is a stylized example, real world practice was far more complex). Instead of a 9.25% capital ratio, applying the 100% bucket would have reduced the ratio to 7.14% (10 Capital/140 RWA). You can hold a lot more assets for a given level of capital at these lower RWA’s (dark leverage).

What we need to think about for 2008 and after is this process in reverse. What happens if your “qualified” guarantee runs afoul of the accounting rules? There are all sorts of tests for hedging effectiveness, including triggers like the ratings downgrade of that contract counterparty.

Thus, if you as a European bank have achieved “regulatory capital relief” from AIG and then AIG gets downgraded, your balance sheet leverage must reverse. Your $40 in assets that were in the 20% bucket with AAA-rated AIG now are on review to be put instead in a higher one, if not all the way back to 100% where it all started (Tier 1 ratio goes from a healthy “no problems here” 9.25% capital ratio moving rapidly toward a “what is really going on with that bank” 7.14%). Thus, your capital regime very quickly becomes in danger of falling for one simple downgrade – no cash losses required anywhere.

But, that is not the end of the story. If AIG is downgraded in normal times then you might treat with a competitor for a replacement. It would cost a little more on contract premiums, reducing somewhat the rate of return, but otherwise this form of leverage could be easily maintained. In far from ideal times, however, AIG is not the only firm getting downgraded.

Therefore, the cost of protection skyrockets as demand shoots through the roof while supply is further and further restricted (which, by the way, was the primary way in which these illiquid assets were marked-to-market, the price of CDS). Leverage by necessity must contract systemically, leading often to fire-sales at firms who have no other choice but to dump these assets and book a loss before the capital game turns all the way against them. The self-reinforcing cycle becomes panic. How else did Bear Stearns achieve 35 to 1 leverage? The bank still failed even though it was by the Basel rules still “well capitalized.”

As questions about capital mount, funding is further and further restricted until like Bear or Lehman (or Citi) it is removed sufficiently for bankruptcy. What good is a dollar swap in that situation? Royal Bank of Scotland might have been able to achieve partial replacement of its eurodollar liability structure by putting up limited collateral with the Bank of England for dollars instead of more flexible collateral on offer in private repo. RBS, however, still has (had) the problem of its balance sheet leverage working against it, leading it directly into the churlish arms of the British taxpayer.

That is, of course, yet another element in the panic and its aftermath that defeats traditional liquidity – collateral. The dollar swaps were from the very start collateralized all the way around. The Federal Reserve is given foreign currency by the counterparty central bank with an agreement to buy it back at the same exchange rate. That foreign central bank then auctions those dollars it obtains (in a deposit account at FRBNY) to local banks on collateral according to its schedule.

What if a European firm that held mostly (at the margins) US$ MBS, because they more easily fit in “regulatory capital relief” leverage, can no longer use them in repo? It’s another reason to get rid of those assets to obtain something like UST’s or other OECD sovereign debt. Or hope that whatever central bank starts loosening the collateral eligibility for its dollar auctions (which, of course, many did).

First there were questions about capital, then there were questions about collateral, and finally panic. In either collateral or capital, what recourse did the Fed provide? This is why TARP was changed and further why nationalizations were in many jurisdictions the only political option (and why even in the US questions about it lingered well into 2009, and the economic carnage that accompanied that lingering). Liquidity, meaning money, was not what was on the Fed’s balance sheet, or even, as the QE’s, how much and in what form the Fed might add to them in the future.

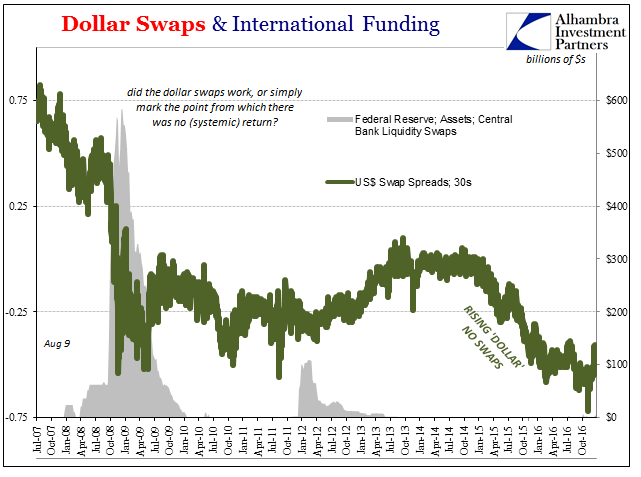

As compelling an indictment against the dollar swaps as that is, the evidence was repeated by what followed shortly after the 2008 Panic. As the Federal Reserve noted in its press release from May 2010, not even a year later:

In response to the reemergence of strains in U.S. dollar short-term funding markets in Europe, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, and the Swiss National Bank are announcing the reestablishment of temporary U.S. dollar liquidity swap facilities. These facilities are designed to help improve liquidity conditions in U.S. dollar funding markets and to prevent the spread of strains to other markets and financial centers.

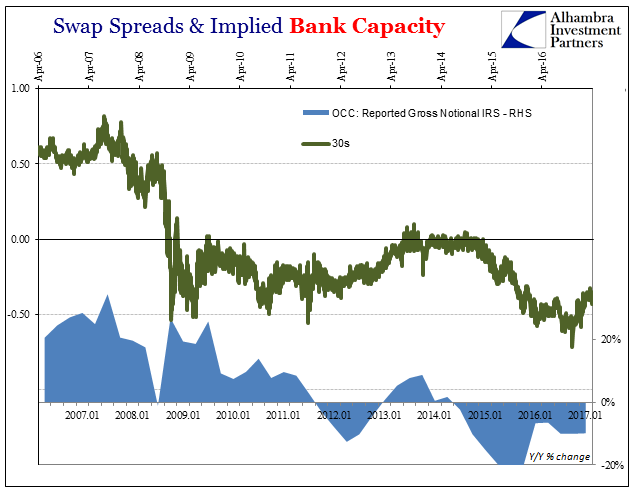

Yet, they did not “improve liquidity conditions in U.S. dollar funding markets.” It all spiraled once more out of control despite a second US QE, so that by early August 2011 the FOMC was actually forced to debate bailing out the repo market (the story of the BIS gold swaps in 2010 is also particularly interesting as it relates to offshore dollars at the time and the desperation for them). The ECB was beset by numerous problems which it finally threw the LTRO’s at hoping a flood of euro liquidity would end the uncertainty (it didn’t).

To address their (dark) leverage problem, many European banks had ditched their MBS holdings for sovereign bonds. That meant the lower RWA as well as being acceptable in private repo – at least until those markets realized Greek, Portuguese, and Italian government debt wasn’t really worthy of a zero risk assessment (and small repo haircut). They had moved out of the frying pan and into the fire.

I won’t get further into 2011 because I’ve done so before (as well as the economic costs of that 2011 event, the 2012 slowdown that has likewise become clearly permanent). There are other complications requiring attention, too. We often focus exclusively on liquidity users without more complete consideration for liquidity providers; and in the case of the eurodollar system, what it really means that almost always providers were and are also users and vice versa. Unfortunately for today, that will have to remain the case, meriting but this single mention or tease in abeyance of future discussion on the topic.

There was a (so far) permanent break in the global money system that dollar swaps just could not meet. They were the wrong type of solution, and therefore no solution at all. They started out like all the other monetary policy programs, poorly designed and ill-equipped. And like those that followed, especially QE, as these efforts failed to achieve significant positive results, they were merely expanded in volume, a larger number of the same thing. If it doesn’t work, do more; the real motto of all central banks, crafted after repeatedly being confronted by the first part of it.

Again, a central bank doing more is not a sign of success but a signal of how much it is getting worse.

There’s a thousand different things (slight hyperbole) that dealers do central bankers know little about (no hyperbole). Dollar swaps are a tempting study in what little might have gone right because they sound so 21st century. In truth, they are as old as money. Ironically, it was foreign dollar swaps (between an overseas central bank and offshore private counterparties) that in the sixties helped legitimize and build volume for the very eurodollar market that has now failed.

During the crisis period they were a 1960’s view of the 1930’s being applied to money of the 2000’s. It’s really no wonder they didn’t work, twice, and played no role at all in the third major liquidity (“rising dollar”) event of the last lost decade.

Stay In Touch