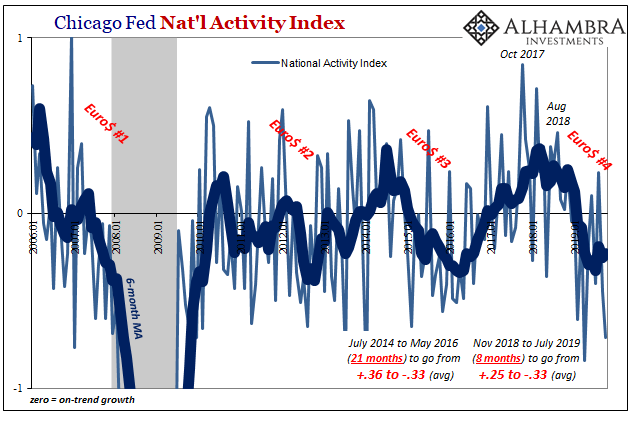

The Chicago Fed’s National Activity Index (NAI) fell pretty sharply in October. At -0.71, that’s a reading which suggests the US economy may be operating significantly below trend. Fifty-eight of the 85 monthly indicators which make up the statistic made negative contributions.

Of course, “below trend” is an imprecise term and doesn’t by itself stand up to the one question for which everyone wants an answer.

Recession or not?

While that’s where the public’s interest mostly comes in, recession isn’t necessarily the result we need to worry about. Sure, a nastier form of downturn can be especially unhelpful, but what we all need to realize is that any downturn at this juncture is going to be seriously harmful.

And that’s already in the numbers, not just this Fed branch’s NAI.

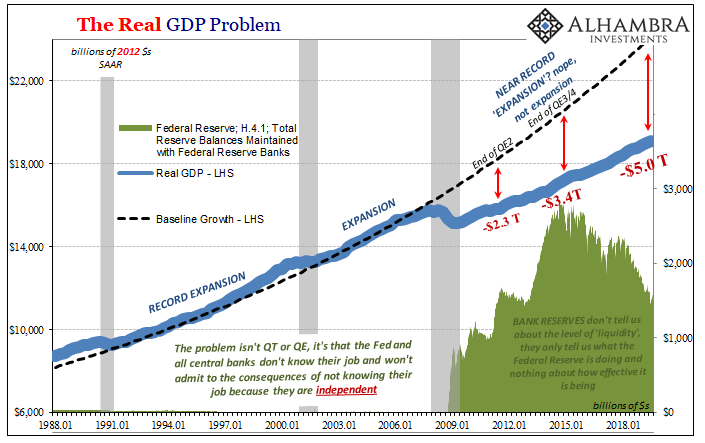

A big part of the problem is perception, the mainstream idea that because there hasn’t been a declared recession in over ten years the US economy has been benefiting from a record expansion. Ever the binary option, we are led to believe that since there hasn’t been a cyclical trough before today that there must have been a boom at least up to and including right now.

Therefore, mainstream interest really isn’t about assessing the overall situation for what it is, rather it is in keeping with that perception. Does recession spell the end of a decade-long boom? That’s really all anyone means.

To that end, the Chicago Fed NAI can only offer some sense of those specific risks. Historically, it’s when the index averages below -0.60 that we should worry about classical recession. October’s number of -0.71 follows a September reading of -0.45 (revised) and August +0.23 (also revised). In other words, the NAI is noisy month-to-month, which is why the average is holding at around -.25 or so.

As of right now, that’s not nearly enough to suggest recession at least as far as this one tool is concerned. But an average holding at around -0.25 is the last thing anyone should want to see.

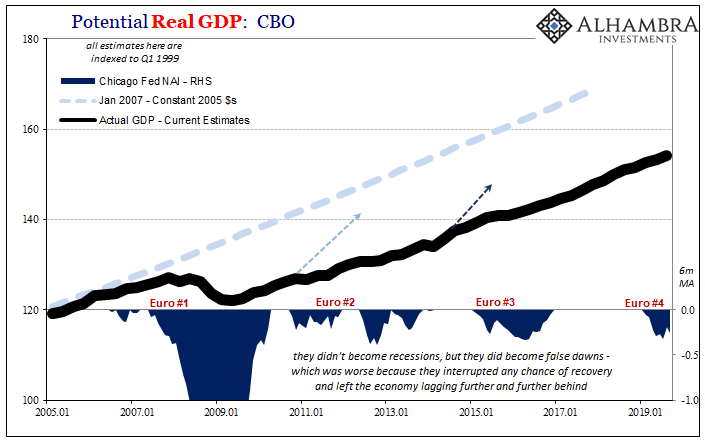

According the NAI, the US economy shifted to somewhat below trend earlier this year (February). That was when the 6-month average flipped from small positive to small negative. Thus, the average has been consistently negative for nine months and counting – a substantial enough stretch which warrants every consideration about downside risks.

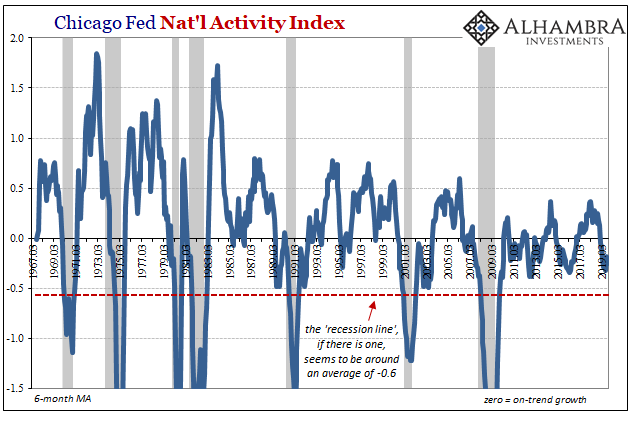

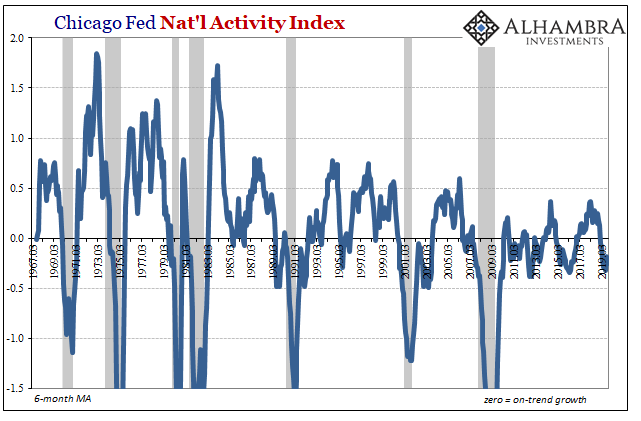

The series history going back to 1967 shows persistently negative NAI numbers equal recessions. In 1995, for example, there were a couple months of serious negatives that pushed the average below zero but only for one five-month stretch. Bond massacre-related worries not really reaching the proportions of a downturn or stall risks.

The last time the index spent much time in the negative was, of course, three and four years ago. The 6-month average flipped in February 2015 and then spent the next 21 months suggesting sustained below-trend growth. And that is exactly what occurred, even though no official recession materialized.

In many important ways, that near recession or lack of full-blown recession was actually worse. Because it didn’t sink to the level of an NBER declaration the myth about this decade’s expansion continued unchallenged. The real underlying problem remained completely hidden because of a technical definition; the problem was real enough, just no one knew anything about it.

Recession wasn’t actually the most pressing problem in 2015, just like it isn’t now. And you can see what I mean in the NAI data:

While everyone is focused like a laser on the tracks below zero, you tend not to really appreciate how little upside there has been since 2009. And that’s where everyone needs to focus.

Which is exactly where the downturns are most lethal. Downturn simply means a guaranteed multi-year period when economic conditions are going to be significantly less than what we need them to be. Regardless of recession, the economy will squander several more years without any effective upside (no matter how many times the word “boom” gets printed in the mainstream media and academic literature).

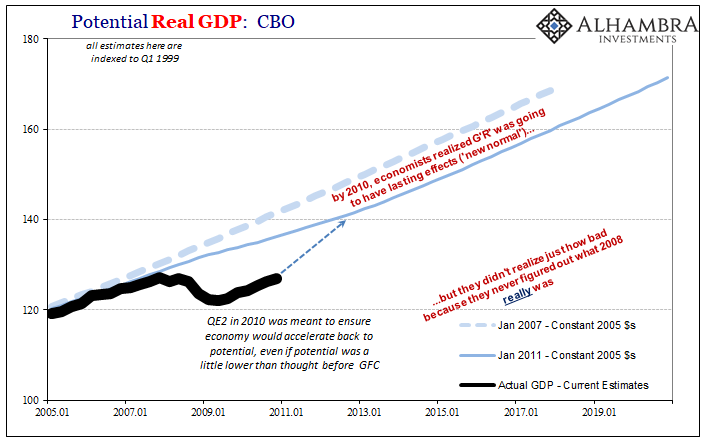

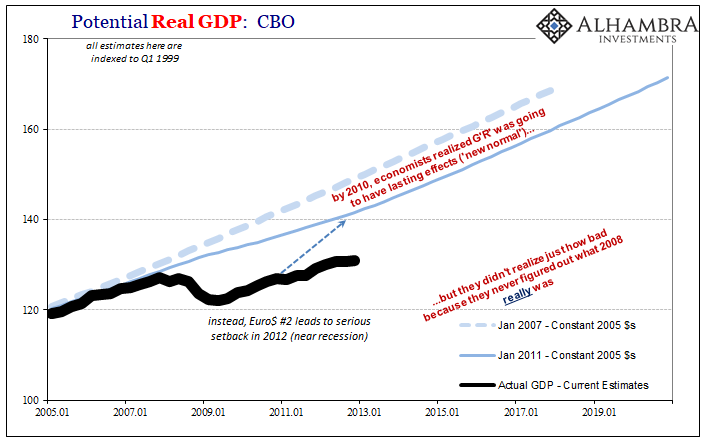

To demonstrate what I mean, we can take the NAI data and cross reference it with GDP figures and estimates for economic “potential” – in this case taken from the CBO’s econometric models, which are practically the same as those used all over the world at central banks and by Economists in academia.

By 2010, Economists and Federal Reserve policymakers had already begun to suspect “something” was wrong. But, not having made a close enough (or honest enough; subprime mortgages remaining the official explanation) examination of the “somehow” Global Financial Crisis they were unsure of what to make of this “new normal.”

It was still widely expected that the US economy would recover from the Great “Recession” – even though in 2010 there were further warning signs all throughout the global financial system conditions still weren’t right. Ben Bernanke’s Fed undertook QE2 late in 2010 as a kind of insurance to keep the economy on a recovery trajectory despite acknowledging how potential may have been less than once thought.

Rather than QE, you would think central bankers would have been far more interested in the latter.

The recovery never happened. Instead, Euro$ #2 did and though it didn’t lead to a recession in 2012 it did create a substantial downturn which the NAI recognized with its 6-month average remaining below zero for 17 months beginning with June 2012.

In other words, no recession but far more importantly no recovery! Just when it was time to escape, the untimely and “unexpected” downturn spoiled everything.

By focusing instead on the lack of recession, the size of the downside, officials in particular missed the real damage that was only building. And because this was a second instance, it offered compelling evidence about how no one was looking in the right place.

This interruption in the upside has had a profound effect on the economy as well as the mainstream interpretation of it. To begin with, this is rarely if ever discussed in public. Quite quietly, Economists and central bankers reacted to Euro$ #2 (while not recognizing it was Euro$ #2) by starting to believe there was something wrong with the economy – instead of contemplating how it might be they who were the ones missing something.

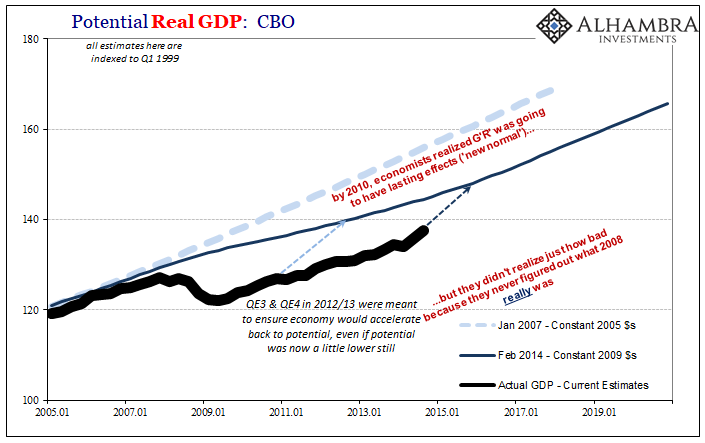

What that meant by 2014 and Reflation #2 was how even though “everyone” still professed unflinching faith in QE’s 3 and 4, they didn’t actually fully trust in them. The CBO, as the Fed, had substantially reduced “potential” because of how there continued to be a lack of upside recovery.

By the time 2014 rolled around, officials still foresaw accelerated economic activity and output, it was forecast to be stunted and not really all that robust. That’s another part of what they left off from “the best jobs market in decades”; how that awesome economy of 2014 wasn’t even supposed to be as good as how it was going to be just a few years earlier. The very notion of recovery itself was being downgraded simply because no one could get a handle on what even Ben Bernanke had by then begun labeling “false dawns.”

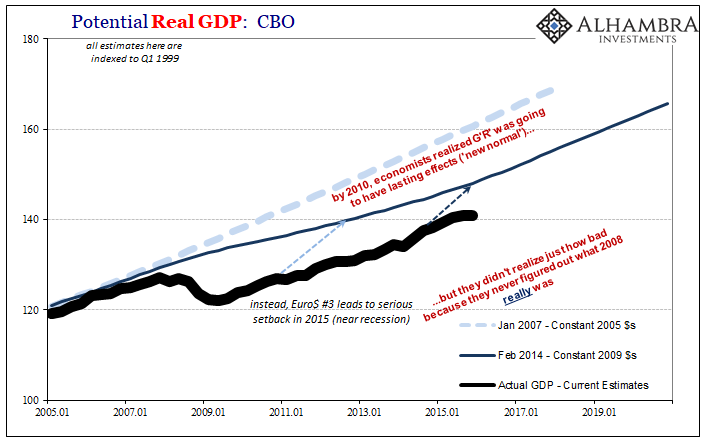

And just when the stunted recovery of Reflation #2 was getting going – another eurodollar interruption, the third. As noted above, the NAI’s average turned negative in February 2015 and remained below zero for a long enough stretch to corroborate another devastating downswing.

Like #2, Euro$ #3 didn’t produce a full-blown recession, either.

But it did repeat the absolute worst aspects of these non-recession downturns, mainly several more years of falling further behind. The near recession pushed the economy that much further away from its pre-crisis baseline, further away from even the corrupted “new normal” baseline of 2012. Economy, recovery, and growth were all transforming into much smaller concepts. Once aware, you would think this would be a big deal.

And while everyone was again focused and relieved by the lack of recession in 2016, that really didn’t matter (just ask Mrs. Clinton).

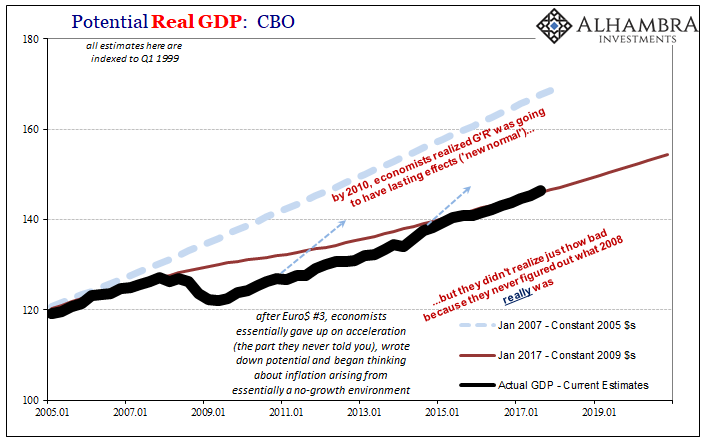

By the time Reflation #3 rolled around, standard measures of economic potential had been so utterly downgraded that whatever small level of growth in Real GDP the economy was managing at the time was considered a “boom.”

In the end, because Euro$ #2 and Euro$ #3 never pushed the economy into recession they were quickly forgotten even though they did enormous unexposed damage. They were more than enough to force it so far off track that the whole economic paradigm has been rewritten – just not in public. Even 2017’s inflation hysteria was predicated on so much less than you were led to believe.

A recession is a temporary deviation from potential; these near recessions lead to deviations of potential. I cannot overstate just how devastating that is.

And the NAI right now already puts the economy squarely in yet another downturn position, which even if it never rises to an NBER declaration it still will mean several more years falling further and further off-track. That’s the real downside risks we all should be seriously worried about.

In short, whether or not the economy experiences “recession” only matters for figuring out just how much further behind the world will end up (because this isn’t just a US problem). Instead of focusing in on recession or not, everyone should be asking where’s the recovery? Where did that “boom” go, and why didn’t it ever legitimately boom?

The only way we get this level of confusion is the focus on recession and how there hasn’t been one for so long. What’s really concerning isn’t the potential for recession in 2020, what’s actually alarming is how there’s more than enough data including the NAI to see ahead that many more years on the wrong side of right potential. Can we really afford what a broad stretch of data has already declared to be a third false dawn?

The Fed’s forward-looking number doesn’t give us any indication yet of recession, but it already gives us more than enough of the worst case.

Stay In Touch