It wasn’t the first time it had happened, but to that point it did suggest something had changed. Things were going wrong and afterward the very idea of wrong took on an even more disastrous nature. On Monday, September 29, 2008, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted nearly 778 points. It was the largest single day’s point loss in the index’s history.

As luck would have it, this was a record that would stand until early February 2018.

In percentage terms, the penultimate trading day in September 2008 sliced about 7% off the stock index. For the S&P 500, the plunge was closer to 9%. The panic was only beginning.

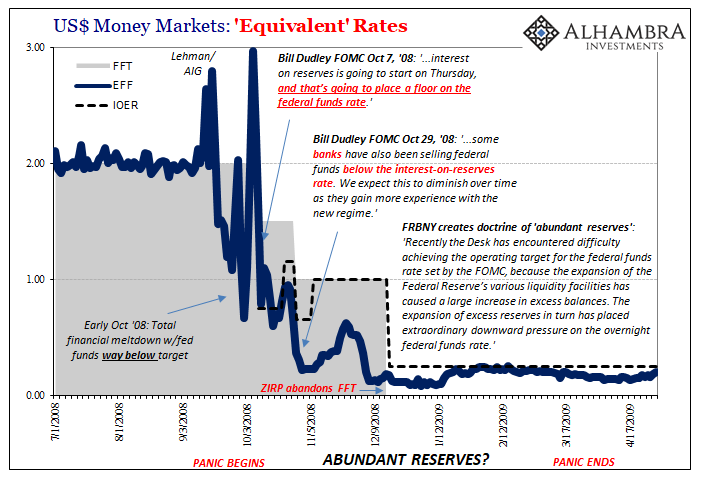

And yet, at the close of trading the day before, Friday, September 26, the effective federal funds (EFF) rate had been 1.08%. What was really weird about it wasn’t just how low it had been but more so that it was 92 bps below the Federal Reserve’s target of exactly 2%. Even after the violent session on Wall Street had concluded on Black Monday, the effective fed funds rate was still 44 bps less than the policy demand.

It’s not quite how you picture the panic.

Outside of a few days here or there, three specifically (September 30, October 7 and 8), EFF would remain way below the monetary policy target rate for the duration. It didn’t seem to add up, and remains to this day one of the biggest unanswered discrepancies in modern monetary history. A clear and undeniable global panic when there was way, way too much money?

This doesn’t mean, however, that authorities haven’t proffered their response. It’s just that how they’ve described these events is so disturbingly untrue. You begin to develop the sense that these “best and brightest” who the nation and the world had entrusted with enormous responsibilities just might never have been up to the task.

And haven’t learned much from their (many) errors.

While global financial markets were being actively burned down, the FOMC would have to spend some of its attention on EFF. When your entire monetary policy doctrine relies upon a monetary policy target, you have to make the market hit that target else the entire world will begin to wonder what it is you can actually accomplish. Before ever getting to more complicated things like a panic or saving the economy from one, you first have to be proficient at the basics.

To address the persistent undershooting of EFF, the FOMC requested and received statutory approval to move up what’s called IOER. As part of a minor modernization effort begun years before, the Federal Reserve had intended to pay interest on excess reserves at some point anyway. The circumstances surrounding September 2008 and the specific misbehavior of EFF seemed an opportune time to get a head start.

Bill Dudley was relieved. On October 7, 2008, with the panic in full swing, FRBNY’s head of Open Market Operations told the Committee that IOER would cross one critical item off the list of things going wrong.

MR. DUDLEY. That’s why getting interest-on-reserves authority was very, very important. As Brian has said in earlier briefings, interest on reserves is going to start on Thursday, and that’s going to place a floor on the federal funds rate. So we think we’re in a situation where we have a very important tool that will allow us to expand the balance sheet but maintain control of the federal funds rate. So we’re not going to be compromising monetary policy. [emphasis added]

What he had meant about “compromising monetary policy” was specific. The Fed had engaged in, essentially, balance sheet expansion even before QE. These emergency liquidity measures, mostly dollar swaps arranged with foreign central banks, had ballooned the Fed’s asset side, which in turn increased the level of bank reserves (double accounting).

These excess reserves, Dudley said, were ending up being dumped back in the federal funds market – and that was why EFF was pinned below the policy target – since the Fed was being forced to create too many of them. During the second half of September, the Fed had tried a couple of different things, including reverse repos, to “drain” these reserves but was obviously unsuccessful.

IOER was going to change that. This would give the FOMC freedom to do whatever it wanted on the asset side – to expand as it might become necessary given the gravity of the situation – all while still keeping EFF in line with the monetary target “without compromising monetary policy.”

It didn’t work. IOER was initially set at 75 bps, three quarters of a percent below the federal funds target (FFT) of 1.50% (it had been reduced by 50 bps on October 7). By October 17, EFF (60 bps) fell below IOER.

A few days later, October 23, IOER was raised. Rather than fixed at 75 bps below FFT, it was set at just 35 bps underneath. The day the change was made, EFF moved up to 93 bps (with FFT still at 1.50%) but was back down to 67 bps by October 28. To get a sense of where things stood at the end of October, on that same day Citigroup and eight other banks received their first TARP funds.

Also on October 28, appearing before the FOMC a little annoyed, more so confused and stunned, Bill Dudley told its members:

MR. DUDLEY. …some banks have also been selling federal funds below the interest-on-reserves rate. We expect this to diminish over time as they gain more experience with the new regime. However, other factors, such as concern with their overall leverage ratios, could cause this phenomenon to persist. As a result, there has been a significant amount of federal funds rate trading below the interest-on-reserves rate.

So, not a floor.

The full weight of the panic would continue to harass and destroy the global economy well into the next year. It wouldn’t end until early March 2009 [corrected for typo] (FAS 157, known as mark-to-market, as covered in Eurodollar University). The economic costs have been staggering and continue to pile up as central bankers puzzle over how that could be.

In the narrow context of EFF and IOER, the Federal Reserve has put forward a doctrine of “abundant reserves.” How else could they explain this discrepancy? Here’s what FRBNY had to say as things were going down in late ’08:

Recently the Desk has encountered difficulty achieving the operating target for the federal funds rate set by the FOMC, because the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s various liquidity facilities has caused a large increase in excess balances. The expansion of excess reserves in turn has placed extraordinary downward pressure on the overnight federal funds rate.

Straight away you have to ask, what good are reserves if they are abundant and the whole world melts down anyway? According to the doctrine, you aren’t supposed to ask that question.

Therefore, the episode teaches us two very important lessons. First, there’s obviously much more to the financial picture than bank reserves. The Fed talks about liquidity in regard to them, but they must be small issue to the wider world otherwise 2008 wouldn’t have happened at least beyond October.

There’s simply no way to reconcile a monetary panic with this absurd idea of too much money or liquidity. The level of bank reserves just don’t correlate to anything outside the immediate arena of bank reserves.

Not abundant reserves, then, the doctrine of abundant irrelevance. The Fed creates bank reserves because that’s what the Fed creates. Sorry for the tautology, but pointing it out is required in this day and age. Interpreting what the Fed creates as money or liquidity is an entirely different matter. Very clearly, there are other more relevant monetary constraints which must be considered first.

The second lesson is that even in the context of its own parameters, the FOMC is as likely to get things wrong as right. IOER is an example, a perfect example, but far from the only one. These people really have no idea what they are doing – and at times it really shows.

Bill Dudley in later October 2008 said it was banks offering fed funds below IOER. In later study, it was narrowed down specifically to foreign banks and the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB) as being the primary culprits (and that’s debatable, especially in 2007 when EFF first started to misbehave in this manner more than a year before IOER).

OK, fine. Let’s point the finger at the FHLB’s. It still doesn’t answer why Bill Dudley, anyone at FRBNY, or the multitude inside the FOMC’s enormous staff didn’t know that beforehand. Why did Bill Dudley sit there on October 7 and in no uncertain terms claim that IOER would be a floor? Either the staff knew the FHLB’s (and foreign banks) were ineligible to receive IOER and thought it wouldn’t make much difference, or they didn’t know at all.

They should have. For decades, their one job was to know fed funds inside and out, mapped out long ago all its possible intricacies.

What emerges is a picture of central bank officials desperately scrambling to make sense of what was supposed to be impossible. You get the sense that these programs like IOER were just thrown together at the last minute, put in place oftentimes because they really didn’t know what else to do. Totally, completely reactive policy.

There does seem to be a whole lot more to this currency elasticity thing, and that means a lot outside of bank reserves. What we mean by liquidity may not even contain them, at most maybe a small issue.

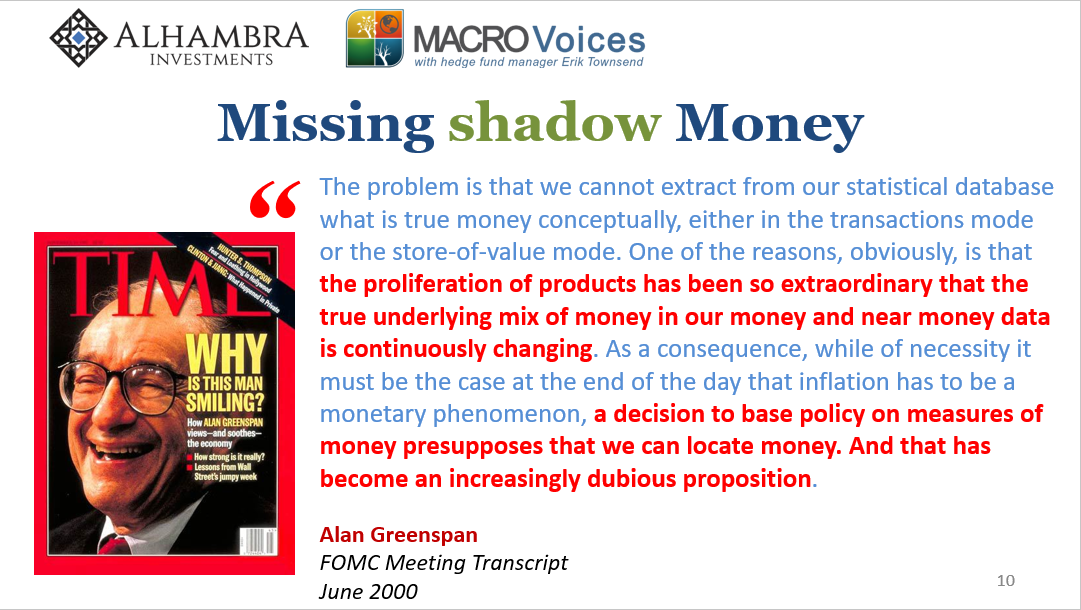

In other words, paging Dr. Greenspan.

Stay In Touch