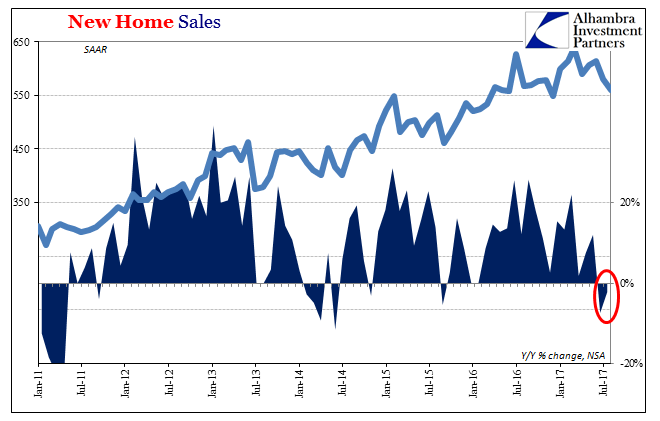

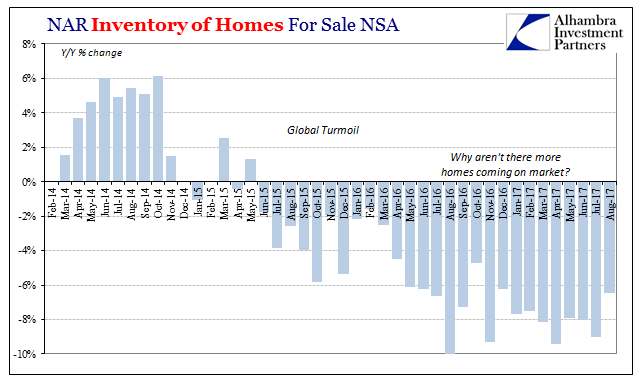

For the second consecutive month, the Census Bureau estimates that sales of newly constructed homes fell year-over-year as well as month-over-month. The data provided by the National Association of Realtors (NAR) for the resale market suggests there isn’t nearly enough supply of homes for sale. Other estimates also published by Census Bureau (permits/starts) declare again that builders aren’t building new units to make up any possible difference.

If builders aren’t overly enthusiastic about real estate development, the estimates for New Home Sales tell us why. Sales were 560k (SAAR) in August, down from 580k in July and 614k in June.

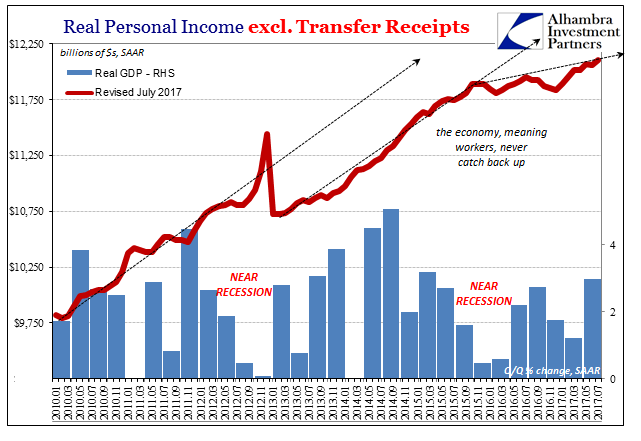

Like almost everything about this economy, what we see is growth that isn’t really growth. In other words, overall the housing market is expanding in linear fashion, which has the effect of making it seem like there is progress and things are moving forward as they should.

Yet, in the fuller context of the last ten years, a context almost always set aside if not ignored entirely, a different story emerges. A rate of 560k or 600k is within the historical range for this series, if at the lower end of it. That’s a false comparison, however, given that the population continues to grow even if the economy doesn’t.

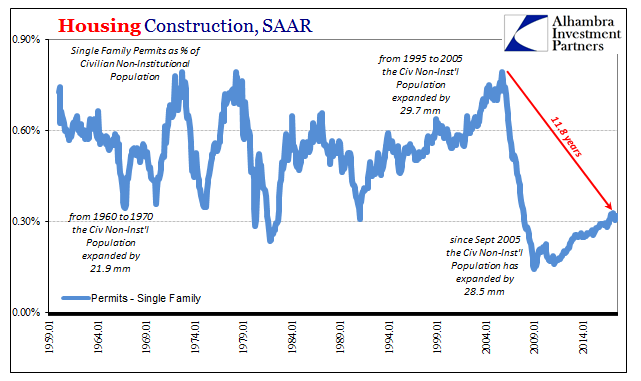

Lower levels of home sales would surely explain lower levels of home construction:

It’s the other part that causes all the confusion and misdirection. The unemployment rate describes an economy at full employment, and therefore at full employment we should expect behavior consistent with what that term has described in the past. In housing and real estate, that means a relatively robust demand for new and existing units.

We are told that the demand is there; what’s missing is the supply. This explanation doesn’t make any sense whatsoever, a total assault on basic economics (small “e”). If homeowners are increasingly reluctant to part with their properties for whatever reason(s), builders would be falling all over themselves to meet this presumed demand especially as prices rise (often robustly). They are not.

Is it more likely that home builders are passing up windfall profits for reasons that cannot be specified (though some enterprising Economists might try to make the labor shortage case here, they would ultimately fail because even if there was a labor shortage in construction it wouldn’t be that for long as builders presented with huge opportunity would pay whatever the market-clearing wage to meet this demand and earn that windfall)? Or is it more likely the demand just isn’t there?

What the full range of the housing data shows is that demand is positive only in comparison to the lowest at the trough. It’s easy to appear healthy when compared to the worst, and ultimately meaningless (so what of all those MBS purchases under QE? More “jobs saved”?).

There are instead two factors to consider, both somewhat related. There is the longer-term hesitation that almost surely is derived from the shrunken labor market. Those 15 or 16 million may be missing from the unemployment rate but we see again that more importantly the economy actually does miss them. Their absence is a clear restraint on reaching and attaining actual growth, in real estate and far beyond.

The second issue is the short or intermediate-term shift after the “rising dollar.” The NAR’s resale data particularly available-for-sale inventory displays a great and sustained reluctance on the part of homeowners to take advantage of rising prices. That is almost certainly a product of the labor market (the timing leaves little ambiguity), too, though again contrary to the unemployment rate.

Uncertainty about employment conditions would be the primary factor in holding back both supply as well as demand; you don’t sell your house if you aren’t sure about wages, hours, or jobs right now; you surely don’t buy one, either (for all the extravagance of the mid-2000’s bubbles and legitimate societal criticisms of mass profligacy, Americans appeared to have learned something from the experience).

From an economics perspective (again, small “e”), the full range of housing data is perfectly consistent with a shrunken economy getting worse for each of these intermittent monetary disruptions. From an Economics perspective, it’s more riddles wrapped inside the enigma of full employment.

Stay In Touch