So much of the growth scare scenario relies upon China’s willingness to end it. By count of conventional Economics, there cannot be a case where a country like China just sits back and lets the economy fall into (further) decay. The argument will always devolve into some form of debate as to economic potential, but surely in a place like that such a thing is up from here not down.

Perversely, the more the Chinese economy slows the more Western commentary assures anyone who will listen to Western commentary that Communist China will spring into action.

These commentators in the West should start listening to China’s Communists.

The most recent template for the conventional approach is found in early 2016. As both the old and updated Keynesian textbooks say, officials are supposed to respond to serious economic troubles with as much “stimulus” as they can tolerate. Back then, the Chinese did that.

But that was ages ago; a regime change of sorts has taken place in between. That way of doing things, the Keynes way, had utterly failed. In the West, there is no chapter on “stimulus” failure in the textbooks because the textbooks always say stimulus can’t possibly fail.

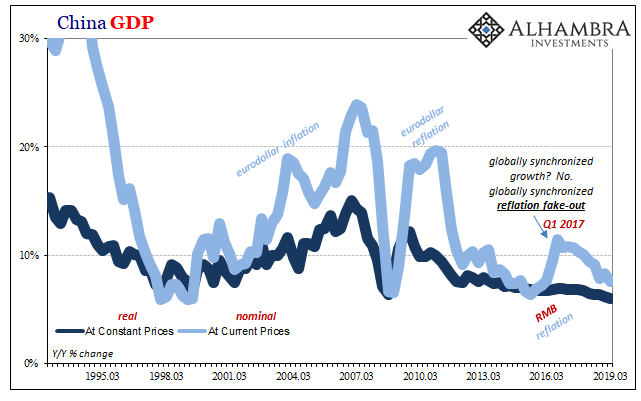

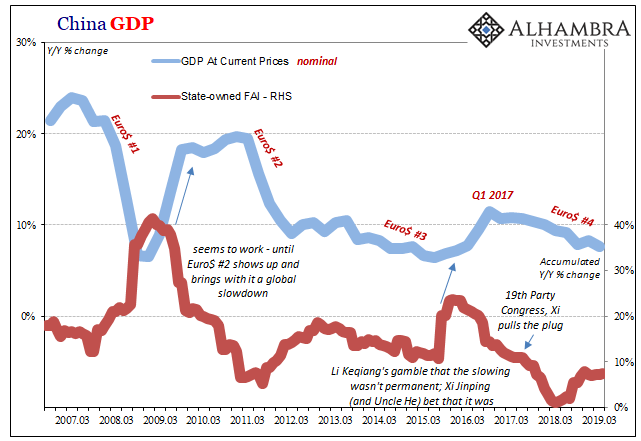

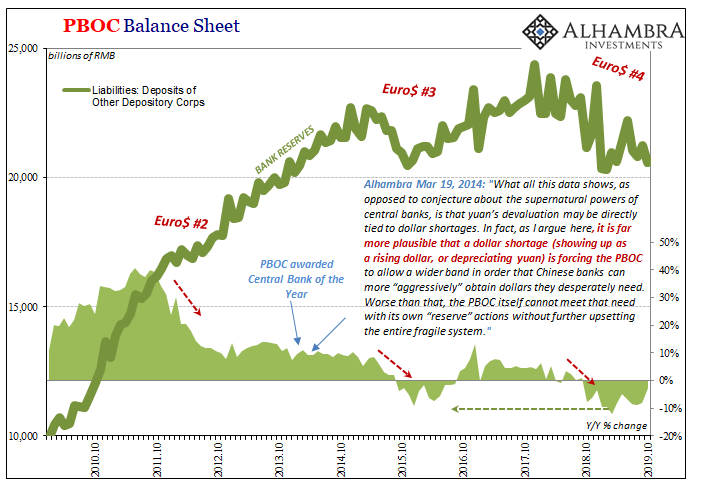

For those looking on interested only in real world success or failure, like strongman Xi Jinping, China’s sort of anti-intellectual leader, 2016’s program did indeed flop. So much was promised and so little was delivered. The results were staggeringly short of any realistic standard (below).

For whatever reasons we may never know, Xi had allowed China’s number two Li Keqiang to follow the textbook approach. Maybe Xi hadn’t yet consolidated his power; maybe Keynes hadn’t yet been enough discredited in Chinese experience. Whatever had been the case, Xi let Li go nuts in early 2016 before slamming the door on it before the end of 2017.

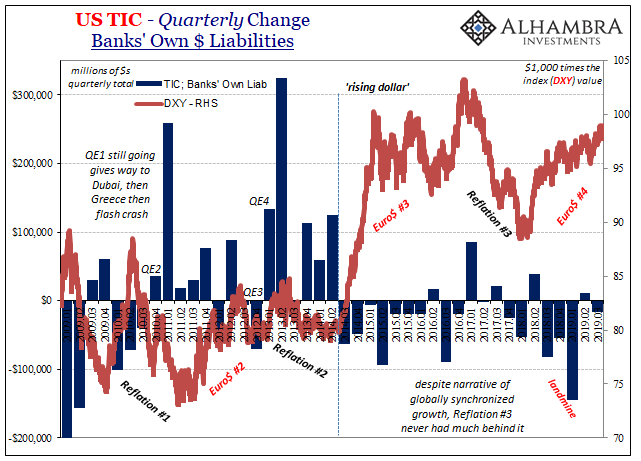

While Western commentary fixated on globally synchronized growth that didn’t really exist, the increasingly authoritarian Chinese leader told the world he wasn’t seeing it, either. If there was meaningful global growth, it wasn’t showing up in China right where it would show up first and strongest.

Knowing how that meant serious trouble internally, Xi set about tightening his grip, battening down the hatches in preparation for serious and prolonged economic upset. Authorities would act on the economy, just not in the way it is written in the textbook. They would hand out meager doses of “stimulus” to be used sparingly and only for one purpose: managed decline.

The Chinese economy would be set in its course, therefore the task before the government was only to make sure it didn’t get out of hand; that it doesn’t spiral downward into a Japan 1989 scenario. There would be no 2016 redo.

If for 2020 there remains any small chance of one, it would be in the mind of Li Keqiang. But Li sounds and acts very differently today than he did four years ago. In fact, he sounds so much more like Xi (and Uncle He) that you have to wonder about what really went on before the Communist Party felt it safe to finally hold that fourth plenary.

Appearing on state-run television last Thursday, Li said:

We must keep a sober mind and realize that the downward pressure is increasing … and be prepared to deal with challenges from the bigger difficulty

What that meant, apparently, was not a massive response but how China’s leadership will reply to the “bigger difficulty” by taking steps to keep the economy within a “reasonable range.” It sounds an awful lot like managed decline coming out of the mouth of the guy who planned and executed 2016’s stimulus explosion.

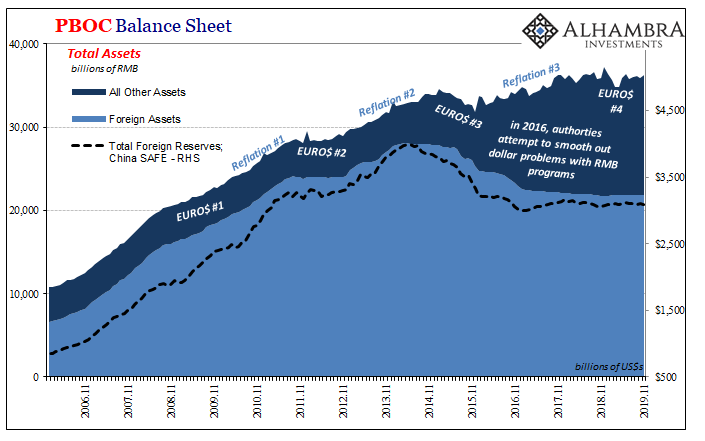

And while it doesn’t sound at all like the Communist government will come running to China’s economic rescue, there’s just no room for its monetary authority. The PBOC is doing all it can to hold to its “neutral” stance. Just to maintain a net nothing, the central bank has been forced to switch gears recently.

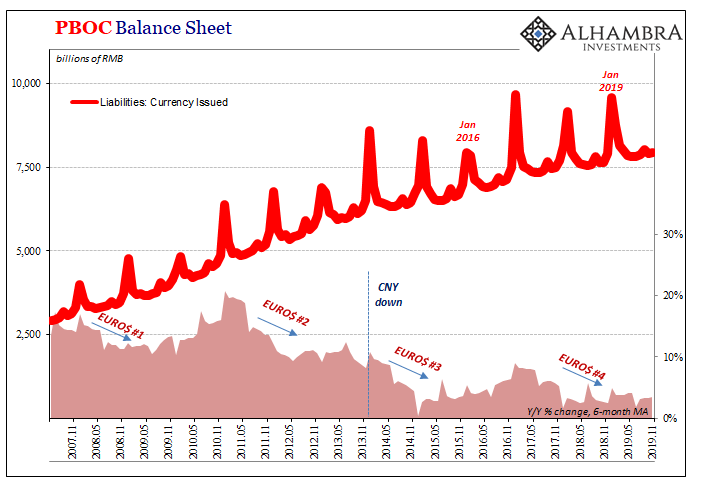

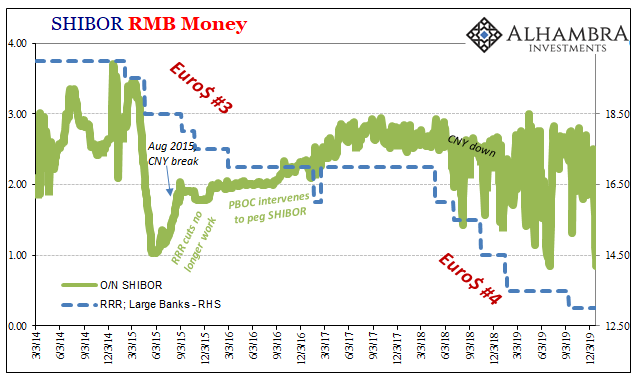

Having first tried to manage Euro$ #4 with RRR cuts, over the past two months officials have instead responded to it with interest rate cuts and more frequent liquidity injections. The rate for the MLF, a medium-term facility used primarily by the largest state-owned banks to take and redistribute RMB across money markets, was lowered on November 4.

Last week, the PBOC reduced the benchmark rate for its 14-day reverse repo after cutting the 7-day benchmark a month earlier. It appears to be a cumulative attempt to nudge the Loan Prime Rate lower (by reducing benchmark borrowing costs, monetary authorities are hoping – demanding? – banks pass them along to borrowers, particularly corporate borrowers).

This is not the 2016 scenario, either. Western commentary keeps calling it “stimulus” and continues to call for more in 2020, but it’s just not there. Going from RRR’s to interest rate influence is not a positive change for anyone expecting a “liquidity flood.”

Rather, this is the PBOC’s very own contributions to managed decline. It will not redo 2016, either, in many ways because it cannot.

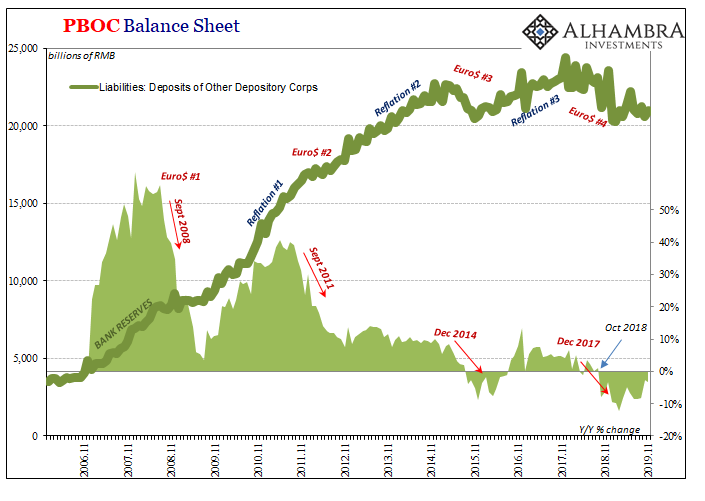

The stats are all the same that you’ve seen detailed here many times before. By virtue of the finicky eurodollar system, the central bank’s balance sheet does not expand; therefore, bank reserves decline and currency float is squeezed in between. Nothing has changed on that front, meaning Euro$ #4 continues to wreak havoc on China’s precarious dollar position (short meets shortage).

Any liquidity injections are not additive but merely trying to fill back in a huge hole already dug out by (euro)dollar woes. Those rate cuts and any others are merely taking managed decline to the next step: if the PBOC can’t contribute dependable liquidity (just look at the volatility in the O/N SHIBOR rate) then it has to try to bypass the money markets and go directly to aiding China’s corporate debt sector (itself in serious trouble).

But the Chinese don’t have a bond market like the US does (nobody in the world has that deep of one, but I digress). Like Europe, China depends (too much) on its banking sector. Ultimately, liquidity matters most meaning that this change to interest rate cuts are an escalation in the wrong direction.

Writing in the Chinese Communist Party journal Qiushi at the beginning of December, PBOC Governor Yi Gang sounded an awful lot like the Li Keqiang of 2019.

The world’s economic downturn will likely stay for a long time. We should stay focused and targeted, while not competitively lowering interest rates to zero or engaging in quantitative easing.

A not-so-veiled shot at Western standard practice. The message from China is pretty clear, increasingly uniform, and it has been for several years now. The textbook Western approach is doomed to failure. Something big – especially in and after 2014 – is holding the whole global economy back, and the Chinese response to that something big is going to be riding it out and hoping for the best.

It’s pretty much what Xi Jinping said in October 2017. If you are and have been hoping that growing economic pressures in China would force the government to act like it did in 2016, you haven’t been listening.

Stay In Touch