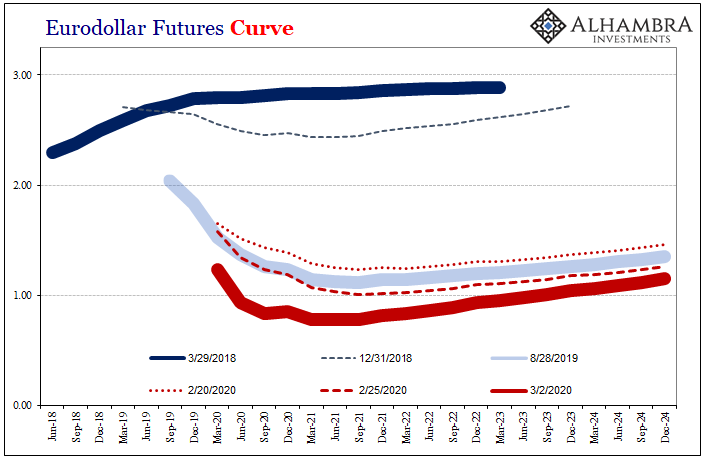

It’s interesting what the eurodollar futures curve has done today. Over the past several weeks, of course, the curve has collapsed though with much more focused buying at the front end of it. That’s understandable given the common scenario being priced in – that the Fed will reluctantly be forced into sizeable rate cuts very soon.

In fact, the current front month contract, March 2020, is priced for 50 bps at some point before it goes off the board in just a few weeks. The next scheduled FOMC meeting takes place on March 16 and 17 – the two days before the March 2020’s expiration.

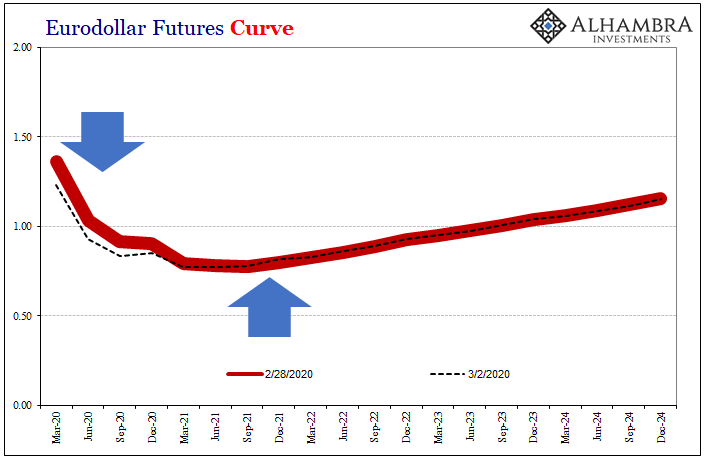

What has happened today, though, is more of a twisting to the curve, one which became even more pronounced in after-hours trading. Like the bond market, there was a late-day selloff in the back end of eurodollar futures. However, there remained a huge bid at the front.

In other words, the way the curve reshaped (slightly) today was an increasing bet for a more immediate and heavier FOMC response at the front which the back end (like the reversal in yields) priced positively (to the economy; slightly higher long run interest rates).

The marginal eurodollar futures market participant, for just today, was saying that if the Fed does make its move soon then it stands a better chance of having the intended effect.

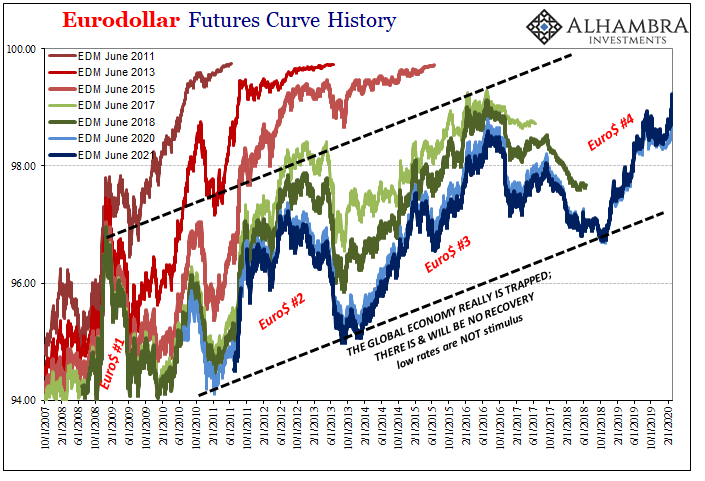

I doubt it will last for one simple truth: rate cuts are ultimately meaningless in the context of what they are to be for. They sure aren’t stimulus. Even here in eurodollar futures, what’s really going on is marginal investors having already made a bundle betting against the Fed and are using the pretext of what is commonly believed about potentially lower rates to lock in profits. That’s why euruodollar futures prices (esp. since 2011) have overall gone up and up across the whole curve.

The rationale is as I described. Fighting the Fed has been a lucrative business for many years.

Do lower rates actually do anything?

It’s a question no one outside of bonds asks; everything about them is taken at face value because…reasons. Hardly anyone contemplates what they are. It is the modern incarnation of the Big Lie. Repeated so often by “everybody”, the public is led to believe there is no possible way it might not be true. After all, Alan Greenspan.

Yet, after more than a decade of NIRP, ZIRP, and low rates around the world, it’s hard(er) to ignore the contradictions all around. Even Economists are having a difficult time with the concept (they don’t really understand bonds, so it is understandable if still inexcusable).

Writing at Central Banking today, former IMF Managing Director and Banque de France Governor Jacques de Larosière dares to examine the relationship.

It is frequently claimed that unconventional monetary policy with zero interest rates is conducive to a recovery in investment, since, by definition, financial conditions are easing. But is there any evidence for this assertion?

No, he finds, there is little evidence that low rates have aided in recovery at least so far as they are supposed to through capex and productive investment. But while good this prominent former policymaker (who will be taken seriously if only because of his credentials) is finally exploring the limits of the interest rate myth, his analysis is already hamstrung right at its start.

Did you catch it in the quote above? Before getting to the lack of economic output, Mr. de Larosière simply assumes “zero interest rates” are “by definition” the same as “easing.” Are they?

That’s the real question. It gets to how everything in banking and money really work, and it isn’t (and hasn’t been for a very long time) the way it is taught in Economics by people like Jacques de Larosière. What we are led to believe sounds intuitive and simple enough; lower rates mean it is cheaper for consumers and, more importantly, businesses to borrow.

The reason it gets to be is because, we are all taught, maturity transformation at the heart of depository banking. Banks borrow in the short run and lend over longer terms. The Fed (or any central bank) lowers its policy rate which increases the profitability of this credit spread and thereby results in more competition to lend credit. A steeper curve and therefor more of everything.

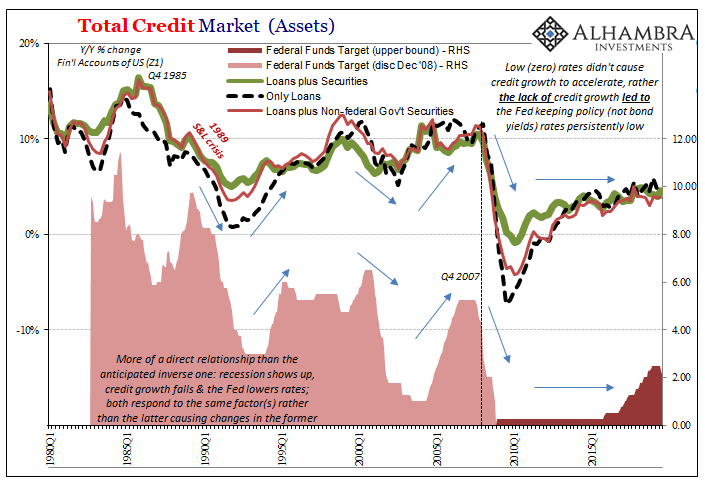

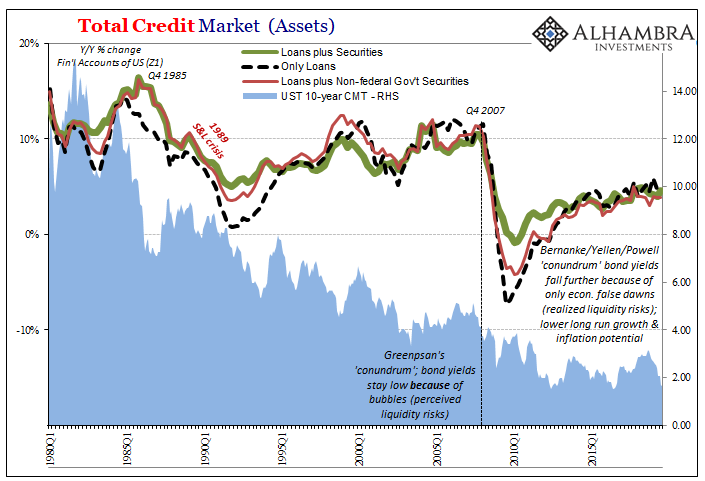

Where’s the evidence for this? The last dozen years haven’t been the only time period to cast so much doubt. In fact, when you examine how rates and credit have behaved, what you find is more a direct rather than inverse relationship – particularly as they relate to the business cycle (recession/recovery).

In other words, the economy runs into trouble which banks perceive as rising risks thereby slowing credit growth. That then has led to the Fed (after a lag, a period of denial) into “rate cut” cycles coincidentally at the same time credit is decelerating. Once the recession passes, both reverse – with monetary policy at an even greater lag (such as 2003).

And it has been this last “cycle” which has put the final nail in the myth’s coffin; zero interest rates didn’t lead to a rebound in credit expansion as you were led to believe. On the contrary, the lack of credit expansion is the key reason why the Fed has left rates so low for so long.

Bond yields simply price the anticipated (so far, correctly) long run effects of this (stimulus failure).

What really happens with “rate cuts” is much different. The Fed uses them to signal to businesses (largely via the stock market) its intentions, and so long as most people in the economy believe in the myth that low rates equal stimulus they will act as if it is. Consumers spend more and businesses hire and invest because the central bank has, essentially, told them to regardless of any real effect in banking.

That’s how central bankers see it in their theories and econometric models. What Mr. de Larosière is finding out is that maybe it doesn’t really work that way over here in the real world. And he won’t be able to figure out why because in his view low rates “by definition” equal “easing” when quite clearly that’s not the case.

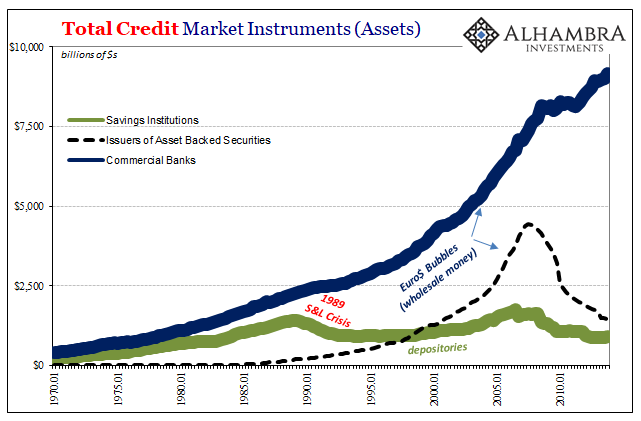

The banking system hasn’t been more purely a depository maturity transformation play. Going back decades, the wholesale approach (which spread globally) has taken completely over. And that’s one where liquidity risks (and perceptions about risk v. return) override everything.

The lack of credit growth instead has had everything to do with those liquidity risks being proven time and again (and again and again and, recently, again). The level of short-term policy rates doesn’t really matter except in mainstream media accounts or, perhaps most Pavlovian, on the NYSE.

The whole concept of “easing” needs to be rewritten as it remains in the textbook, even though history has shown, conclusively, that the myth has everything upside down. Milton Friedman was right; it is higher rates which demonstrate the effects of proper easing and effective money growth, as in the Great Inflation seventies. It is low rates, instead, which signal persistent tight money conditions, just as they did in the thirties around the world.

And now record low yields into the 2020’s and rates heading back toward zero, record lows in longer-dated UST’s. There is no floor under yields and there never was.

Stay In Touch