There he was, the Fed Chairman stumbling through a question about headwinds and transitory factors. No, not Jay Powell in January 2020, this was Ben Bernanke in June 2011. The Fed had just downgraded its recovery forecasts (again) and some in the media weren’t getting it.

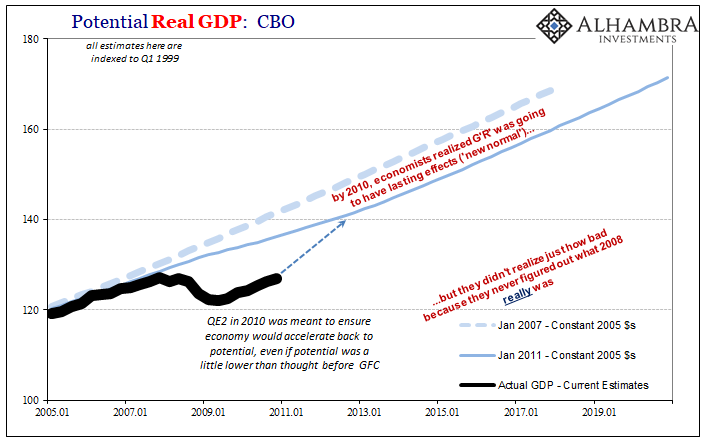

After all, QE2.

It was this enormously powerful monetary agent introduced for a second time in late 2010 just to make sure after the first. The financial media itself couldn’t get enough, or make more of, quantitative easing. It was the ideal they all seem to cheer, the world’s apex technocratic engine masterly concocting just what the global system would require.

But by the middle of 2011, just as QE2 was wrapping up, uncertainty again. Downgrades and headwinds. No one said it out loud, but you can almost tell by reading the transcript some of the assembled pack of journalists really wanted to say to the Chairman: what the hell, Ben?

One reporter sort of did. Greg Ip asked Bernanke to try to explain how the FOMC’s models were revising, downward, both the long run central tendency for growth as well as projections into 2012. The statement accompanying those new forecasts alluded to temporary factors but only “in part.”

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. Well, as you—as you point out, what we say is that the temporary factors are “in part” the reason for the slowdown. In other words, part of the slowdown is temporary, and part of it may be longer lasting. We do believe that growth is going to pick up going into 2012 but at a somewhat slower pace from—than we had anticipated in April. We don’t have a precise read on why this slower pace of growth is persisting.

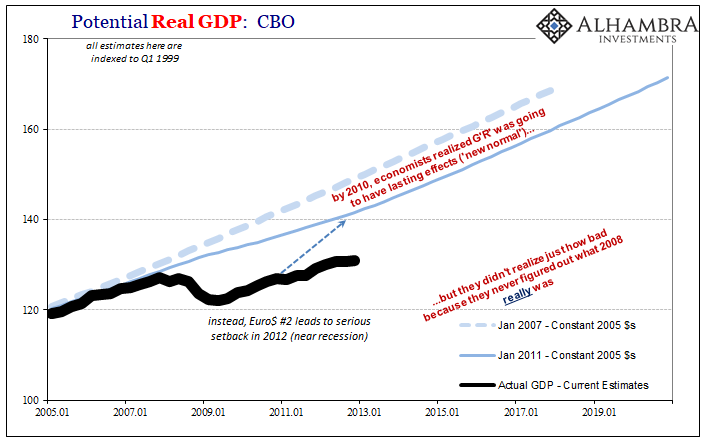

He then went on to say that some of the “temporary” “headwinds” the Fed had been talking about back in 2010 when officials were abruptly forced to launch a second QE they never had any intention to, these were proving “stronger or more persistent than we thought.” That’s another staple of these conversations.

Bernanke in June 2011 would claim the factors holding the economy back, unexpectedly, these headwinds, they were attributable to “weakness in the financial sector, problems in the housing sector, balance sheet and deleveraging issues.”

Again, what the hell, Ben?

What had been the point of QE if not to eliminate weakness in the financial sector and to encourage risk-taking (portfolio effects and inflation expectations) in order to more than offset any deleveraging? That was its purpose. Allegedly.

Not that it did anyone any good, but within a matter of weeks the FOMC would be discussing if or how they might have to intervene in the repo market. Despite $1.6 trillion of bank reserves both the first two QE’s had created presumably on behalf of a bank system that needed this “money”, a second widescale, global liquidity crisis sprang up “out of nowhere.”

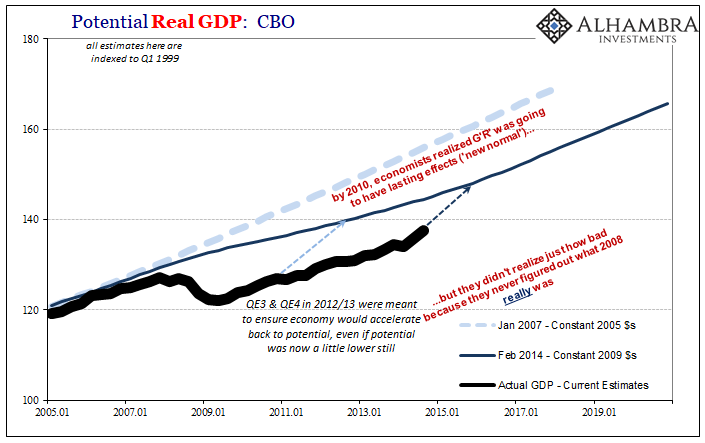

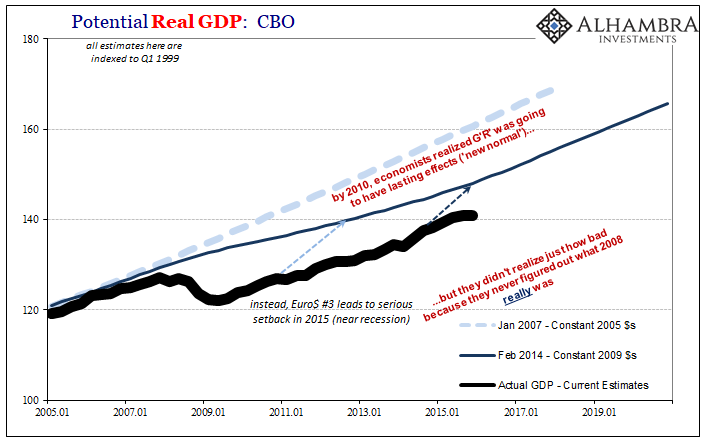

Anyone not specifically attached to the legend might have started to get the sense this whole thing was a sham. Officials couldn’t explain why the economy kept coming up short, especially since the reasons given for it were always, always supposed to be temporary; or, as they say nowadays, transitory.

The scam has merely been extended another nine years to the present day, no small feat. Transitory headwinds continue to dominate. Some longer-term problems, too. At his press conference today following the FOMC’s January 2020 meeting, Chairman Powell still can’t make sense of inflation and wages:

It’s a bit surprising that with sustained levels of historically low unemployment, we haven’t seen wages moving up above that level as we have in other long expansions and other periods of low unemployment.

I don’t mean to get all Sesame Street on the guy; if one of these things is not like the others…therefore? Should inflation have confirmed past recoveries as being completed recoveries, then the lack of both wage and consumer price inflation during the current one, with the unemployment rate plunging past all of those others, means what?

To the FOMC and Jay Powell, it supposedly adds up to the same thing regardless. A strong labor market indicating how great it is underneath all the headwinds.

And then there’s repo. Just a couple of overnight operations, he said. Maybe add a few term auctions. Then turn auctions. How about raising the level of bank reserves (not QE), but only a little way into the new year (2020)? Now at least April.

In terms of what affects markets, I think many things affect markets. It’s very hard to say with any precision at any time what is affecting markets. What I can tell you is that you know what our intention is: It is to return reserve to an ample level. We expect that to happen during the second quarter and our plan, as we do that, is as those purchases get to that level we believe we can gradually reduce them and we believe we can also gradually reduce repo as we reach an ample level.

What the hell, Jay?

His answer was in response to a question about the obvious relationship between balance sheet maneuvers and stock prices, the self-fulfilling prophecy of the puppet show; get the world to believe QE or not-QE is “money printing” and then sit back and watch as investors (more often portfolio managers) act as if it is in order to buy up shares at higher and higher prices with it never once making a difference that Powell is technically correct about QE not directly being a monetary input for stocks.

Or a monetary input at all.

Alas, repo. Shouldn’t it make a monetary difference there? It isn’t, not in the way it is supposed to. If it had been, these non-repo repo interventions of not-QE and other assorted operations wouldn’t have been necessary in the first place. The problem isn’t what the Fed is doing, or keeps doing, it is what the rest of the private system so clearly isn’t.

The Federal Reserve is raising the level of public reserves which everyone can see (rather the whole point) without any mention of what must be going on with private reserves most people cannot because they don’t know a single thing about them…

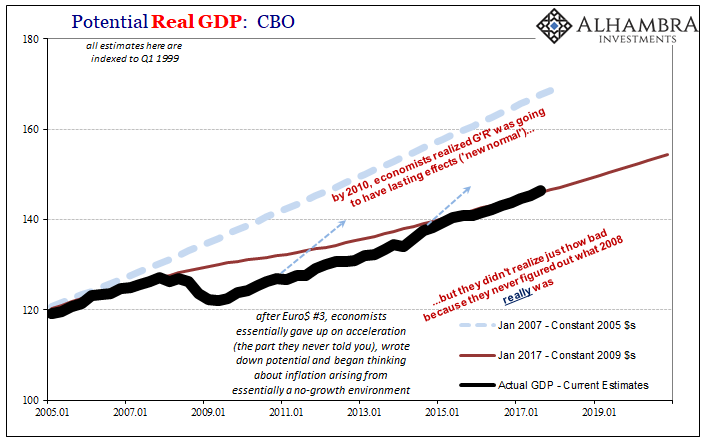

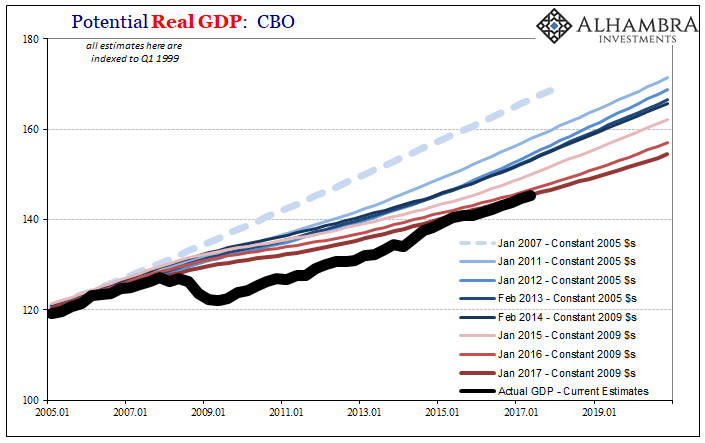

They said raising the level of public reserves from zero would solve the crisis; it didn’t. They then said an even higher balance of public reserves would repair the damage and create a recovery; it didn’t. Finally, they said those things had been accomplished anyway, a fact which would be made known by the anticipated trouble-free hand-off from B to C, paving the way for the world to be able to go back to normal; didn’t happen, either.

For a whole decade, all anyone has talked about was public reserves. In light of yet another false dawn, taking a step back, you might instead get a sense that they just don’t matter all that much. But even now, they continue to be the only thing on anyone’s mind.

From economy to money markets, that private system never performs as desired. There’s always headwinds and they are always transitory. Jay Powell’s missing inflation, like repo’s missing money, isn’t actually so hard to find if you realize you should be looking for them. That’s the key.

The only place where QE does “work” is in the stock market which simply invents new ways to rationalize stretching valuations.

I never said the Federal Reserve wasn’t good. At money, it is terrible. In the economy only false dawns. Complete bungling and incompetence. But money isn’t actually a central bank’s job; managing expectations is. Therefore, the Fed has performed splendidly. After a decade of having to constantly explain away the lack of recovery, it has convinced the world it happened anyway. So successful have they been, the biggest problem truly menacing Jay Powell today is stock prices being too optimistic.

Stay In Touch