Federal Reserve policymakers appear to have grown more confident in their more optimistic assessment of the domestic situation. Since cutting the benchmark federal funds range by 25 bps on July 31, in speeches and in other ways Chairman Jay Powell and his group have taken on a more “hawkish” tilt. This isn’t all the way back to last year’s rate hikes, still a pronounced difference from a few months ago.

The common forecast relies entirely on the subjective interpretation of the labor market. According to the Fed’s models, employment growth remains strong which will support consumer spending and therefore the economy through these “transitory” “cross currents.” In order to ensure this is only what happens, the one-and-done rate cut (as well as an abrupt end to the so-called QT).

When these measures were taken at the end of July, at his press conference announcing them Powell declared:

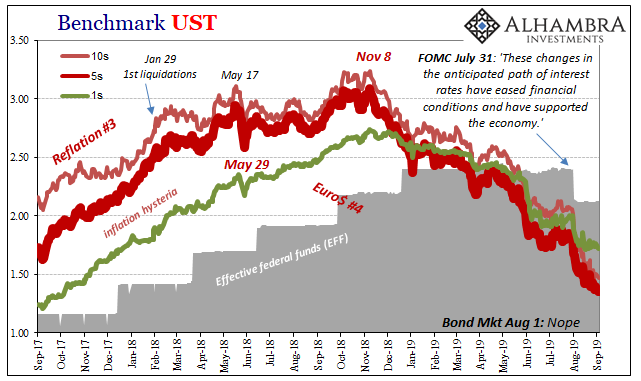

These changes in the anticipated path of interest rates have eased financial conditions and have supported the economy.

It seems as if the FOMC is not data dependent when it comes to its own “easing.” It is assumed that any change so long as it is classified this way will be favorable no matter what. Authorities are not waiting for any evidence to make a reasonable determination one way or another; expectations policy on full display.

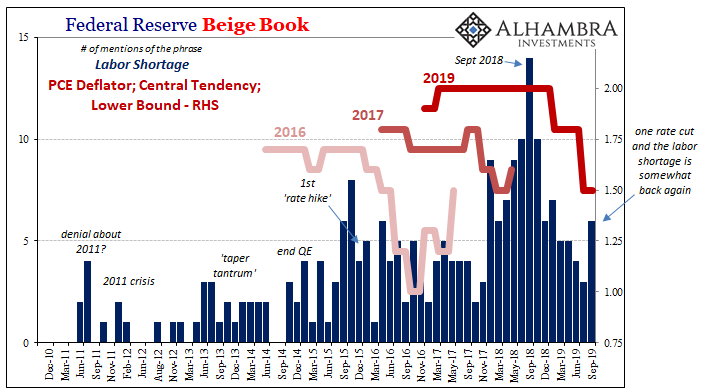

And it might be what’s required of rate cuts has more to do inside the central bank. Not only have markets soured this year, so, too, has officials’ collected self-confidence. Late last year, there was talk of the LABOR SHORTAGE!!! at every opportunity, for one example. This year, despite the unemployment rate dropping to a 50-year low it had quietly disappeared.

It is now conspicuously absent from the media’s front pages, and the LABOR SHORTAGE!!! increasingly had been expunged from the Fed’s very own assessments. Given how the labor market is central to their case and outlook, it should be plastered all over official communications.

The Beige Book, for instance, tells us very little about the actual economy but a whole lot about what policymakers think of it. When they were at their hawkish peak in September 2018, the term “labor shortage” appeared almost everywhere in it.

As one market setback after another took hold following last year’s eurodollar landmine, though, the number of its mentions deliberately dwindled. The economy had grown uncertain, sure, but so had the FOMC’s own confidence in it and themselves.

The latest Beige Book released today for September 2019 brings more of the LABOR SHORTAGE!!! back into its pages. From a low of just three mentions in the last issue back in July, the number doubled in September. One rate cut and suddenly policymakers are more confident among the inner circle.

Powell’s insurance may have been as much about shoring up his internal support as it was anything for the real economy – perhaps the real tip of the spear for expectations policy. Reinvigorate his own increasingly demoralized troops first so that when they go out and talk in public they are refreshed with something they believe is positive in order to instill confidence in everyone else despite all that’s going on.

Maybe the rate cut was meant as much to give policymakers something to feel good about for themselves.

It certainly has done nothing as far as markets go. Whichever way you look, even stocks, the rate cut has accomplished very little as far as assuaging any anguish. Markets haven’t budged; the needle didn’t move.

If anything, there is a better case to be made for the rate cuts (and QT’s fate) having sealed the negative fate. The first rule of central banking is don’t make it worse; sometimes that’s all monetary policy can do. If a central banker does something then there must be something serious requiring attention. A policy change might just confirm negative impressions that are becoming firmly entrenched (even the most optimistic optimists see it too!)

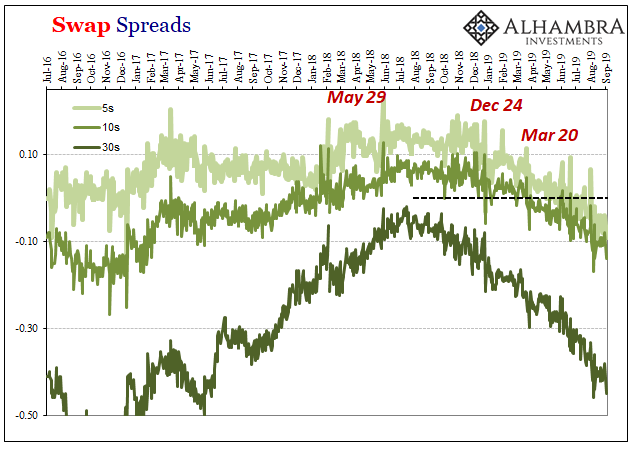

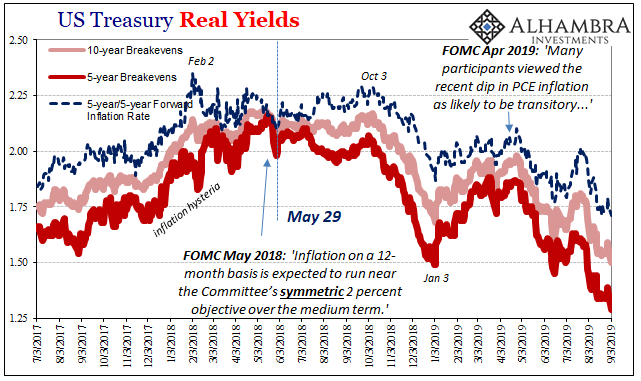

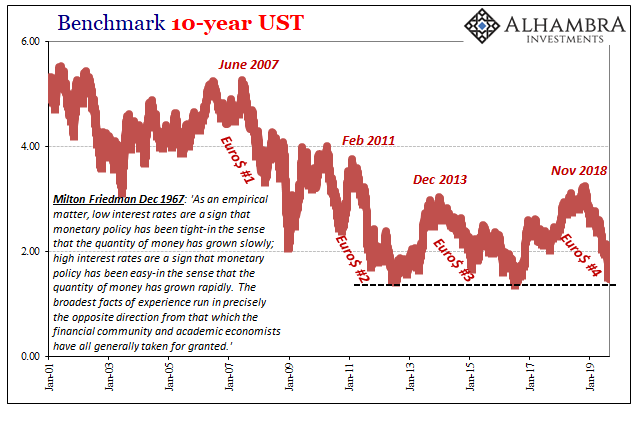

From inflation expectations to the swaps market to the US Treasury curve, the bond market (broadly speaking) isn’t impressed; it has by and large ignored Jay Powell. While policymakers attempt to talk themselves into a rate cut being good enough, bonds (globally, not just in the US) aren’t waiting on expectations. There is nothing positive about not just market levels but more so how quickly (a near straight line) this has developed.

It isn’t lost on bond “investors” (read: global banking system) how the FOMC has been playing only catch-up this whole time. Things started to go wrong pretty early in 2018, the “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” while Powell was talking about more rate hikes than his predecessor Yellen; the landmine late in 2018 which only later did Powell shift into his “pause”; the clear further deterioration in the first half of 2019 while officials spoke of “green shoots” and the like, only to later back off again and reluctantly cut once already.

The bond market has done a far, far better job of predicting Jay Powell than Jay Powell.

So, here we are with officially a “mid-cycle adjustment” that unofficially isn’t being taken seriously at all. Despite what seems to have been a boost to internal Federal Reserve confidence, this “easing” is still being looked at as the first in a series of likely more panicky responses.

As the benchmark 10-year yield once again closes in on its record low, given history there’s too many good reasons for skepticism about the efficacy of a puppet show especially if it maybe was written and put on for the benefit of its own cast members as much as everyone else.

Stay In Touch