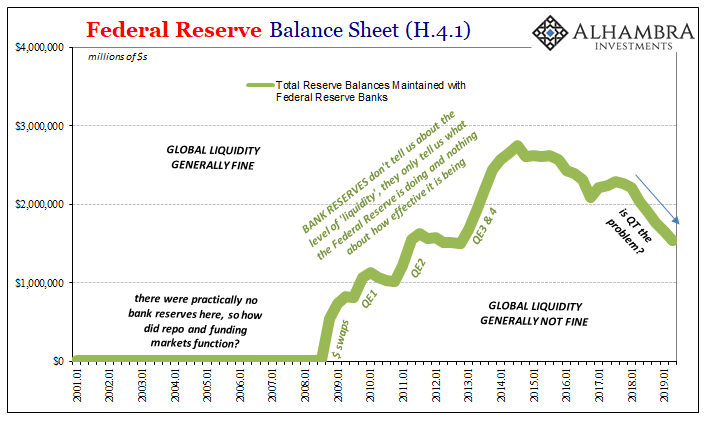

There will be more opportunities ahead to talk about the not-QE, non-LSAP which as of today still doesn’t have a catchy title. In other words, don’t call it a QE because a QE is an LSAP not an SSAP. The former is a large scale asset purchase plan intended on stimulating the financial system therefore economy. That’s what it intends to do, leaving the issue of what it actually does an open question.

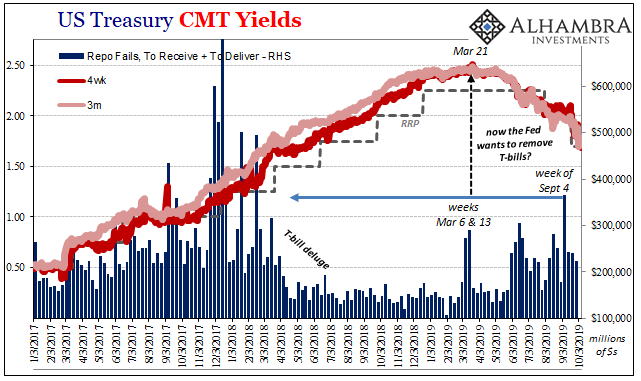

The SSAP is what’s coming next. A small scale asset purchase plan whose intent is only to raise the level of bank reserves. A more technical technical adjustment than the four carried out thus far in IOER and the one in RRP. In short, taking T-bills from the banking system and exchanging them for bank reserves.

It’s hard not to think sometimes that maybe the conspiracy theorists are on to something here. When you step back and look at what they are doing, there are moments when you truly wonder if authorities are actually trying to crash the system. At least to make a bad situation that much worse.

The whole bond market screams systemic collateral shortage and these guys think, well, let’s fix it by…removing the best collateral from circulation. Can anyone in such a position really be that obtuse? It has to be on purpose, right?

But they aren’t really evil masterminds greedily engineering the purposeful downfall of Western capitalism. Central bankers just don’t know their jobs, or even realize that their job is supposed to be money rather than expectations. Never ascribe to malice what is perfectly explained by often staggering levels of ignorance and incompetence.

Bank reserves will go up, T-bills in circulation down, and don’t you dare call it stimulus. I wrote for publication elsewhere tomorrow:

In addition, because, as Jay Powell says, the economy doesn’t need any stimulus, it is doing just fine, none of this is QE. It isn’t stimulus, just another technical adjustment on the road to normalcy. Three birds with one SSAP stone.

What could possibly go wrong?

Over here in reality, the Fed will be simultaneously increasing the level of irrelevant bank reserves, removing top-notch T-bill collateral dealers don’t want to part with, all while not appearing to stimulate an economy quite badly in need of some kind of actual aid.

Strikes one through three?

As I said at the top, I’m guessing there will be (many) more opportunities to talk T-bills, collateral, and liquidity in the not-too-distant future.

Right now, it’s worth revisiting something that appeared in the FOMC minutes published yesterday. That last strike in the threesome: does the economy need some actual aid?

Jay Powell says, no way. Everything is otherwise great because just look at the unemployment rate. It’s glorious, and if we get this repo thing sorted out the US economy will go back to booming. One rate cut, now two, and nothing more except, OK, some overnight repo operations that as things have gone should perhaps be made permanent.

But that’s it, just enough small things to smooth the way for that absolutely strong economy.

The FOMC as a whole, however, seems to have discussed the big “what if.”

Several participants noted that statistical models designed to gauge the probability of recession, including those based on information from the yield curve, suggested that the likelihood of a recession occurring over the medium term had increased notably in recent months. However, a couple of these participants stressed the difficulty of extracting the right signal from these probability models, especially in the current period of unusually low levels of term premiums. [emphasis added]

Extracting the “right signal” from what is perfectly straightforward is transparently blatant dishonesty.

Some unknown number of committee members appears to have been paying attention. As I keep pointing out, ignore the bond market at your peril. I mean “bond market” as a euphemism for the wider global monetary and financial system, all those liquidity and economic indicators that unlike the Fed’s models have done a bang-up job assessing economic, financial, and liquidity risks (mid-September’s repo rumble was no surprise).

All the way back in June 2018, long before any policymaker had ever considered even the vaguest notion of rate cuts, the eurodollar futures curve began to suggest that’s just what would happen. Where 2019 was supposed to have been inflation and a more aggressive Fed, the “bond market” already perceived the risks that would push a reluctant FOMC in the opposite direction.

So far, spot on.

Maybe start taking these signals more seriously?

The minutes, of course, indicate that probably more than a majority just isn’t ready to. Why? Term premiums. Always term premiums. They are like an intellectual get-out-of-jail-free card, a deus ex machina to transform any unwanted market signal into mush.

These people just can’t accept the notion that maybe they’ve gotten everything upside down from Day 1 (which was August 9, 2007). It doesn’t matter what Milton Friedman once said and showed, if interest rates are low over the long run it has to be R* because, in their view, it can’t be tight money – even though all throughout history it’s only ever been tight money.

This time is different?

To admit to the interest rate fallacy would be to confess how the Federal Reserve has accomplished nothing over the last decade plus (as suggested by the repo rumble last month). Therefore, swap some useful T-bills for those inoperable bank reserves!

It takes a rash of dubious regression analysis for these Economists to come up with their own reconstruction of what term premiums must be like. As if their bad math in the DSGE models wasn’t enough, they keep adding on some more to try to unmake what are otherwise straightforward but contradictory warning signs.

As I wrote before, the market unlike Economists at least shows its work when decomposing these bond market signals:

Term premiums are not science nor really math. They are made up and more than that they are rationalizations, truly Orwellian, intended to deny the obvious and straightforward signals coming from the very fundamental building blocks of all finance and economy. The entire notion is purposefully shrouded in unnecessarily complex concepts whose only true use is to attempt to answer for the otherwise inexcusable.

As I often write, Economists don’t understand bonds. But they know just enough of them to understand that they had better change the subject.

The latest FOMC minutes raised the recession issue, and then term premiums quickly changed the subject. Unfortunately, the subject was changed to swapping T-bill collateral for bank reserves.

Stay In Touch