Mario Draghi can thank Jay Powell at his retirement party. The latter being so inept as to allow federal funds, of all things, to take hold of global financial attention, everyone quickly shifted and forgot what a mess the ECB’s QE restart had been. But it’s not really one or the other, is it? Once it actually finishes, the takeaway from all of September should be the world’s two most important central banks each botching their “accommodations.”

It’s only a little weird how European QE was changed and relaunched without an actual vote from by the central bank’s governing council. That body has 25 voting members. Nine have already spoken out against it, either directly in public or in private conversations with members of the media. President Draghi simply declared it a majority consensus.

The most outspoken has been the usual Northern contingent led by Germany and the Netherlands. Their chief complain is as old as the crisis which struck twelve years ago, the same one Europe nor anyone else can seem to ever get past. According to the dissenters, European policymakers are once again punishing prudent savers (NIRP) and rewarding the reckless bubble suspects (QE).

Besides, they say, there’s no need for any of this in the first place. Klaas Knot, the head of the Dutch central bank, called the policy “disproportionate” and voiced concerns over whether it would achieve any of its goals (a near half decade of it up to the end of 2018 apparently didn’t do much lasting good). Jens Weidmann, the notorious chief of Germany’s Bundesbank, famous for being the most skeptical, was quick to complain to German media that Draghi had “overstepped the mark.”

The economic situation is not all that bad, wages are growing strongly, and the spectre of deflation – that is, of persistently contracting prices and wages – is nowhere to be seen.

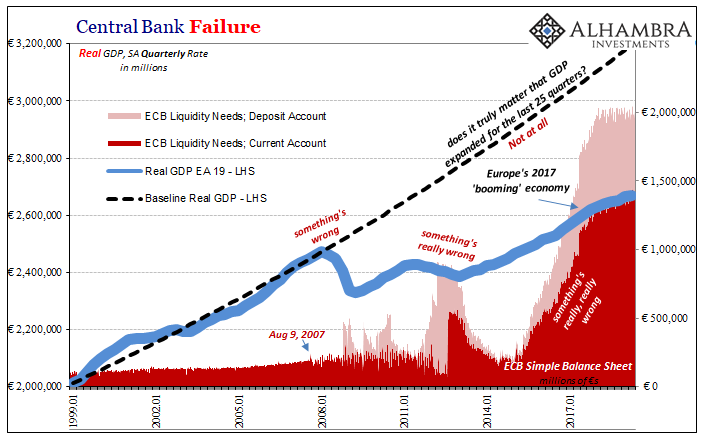

That had become the conventional view after the shock of disappointment early on this year had been absorbed. Draghi had ended 2018 by terminating the last QE and expecting to raise rates, to begin normalizing in a manner that might would’ve pleased the Germans and Dutch for once. But that was all predicated on misimpressions of the economic circumstances.

Draghi had said that in 2017 Europe was absolutely booming and so there was no reason to suspect it wouldn’t just keep going into 2018 and 2019. When Europe’s economy instead hit a wall right at the very start of last year, in January 2018, he dismissed the slowdown as nothing more than transitioning from awesome to good. Nothing to get worried about, no real risks.

It’s turned out to be more serious than that, a change which became noticeable more than a year and a half ago. As such, people are getting very impatient; including, it seems, at least nine ECB Governing Council voters (who didn’t get to vote on QE). The thinking seems to be that Europe has seen the worst; yep, the European economy did become weaker than anyone was expecting, but if there was going to be a recession it surely would’ve shown up before now.

The bottom must be in; therefore no QE is needed.

The economic data seemed to support the idea. For the Continent as a whole, GDP reached its lowest point (so far) in the third quarter…of 2018. It hasn’t sprung back to life, either, rather GDP suggests something like the smallest amount of growth. Not a pickup, but hardly recessionary.

The more it stayed that way the more Draghi’s skeptics have been saying the worst is over. For all the talk and plunging bund yields, they believe Europe is hanging in reasonably well.

The danger has been the flipside of time, though. The longer it goes without growth the greater the danger of falling into recession. That’s been the bond market’s near steadfast view throughout this year. Dismiss weakness all you want, the more it hangs around the greater the likelihood there’s a worse worst case yet to be had.

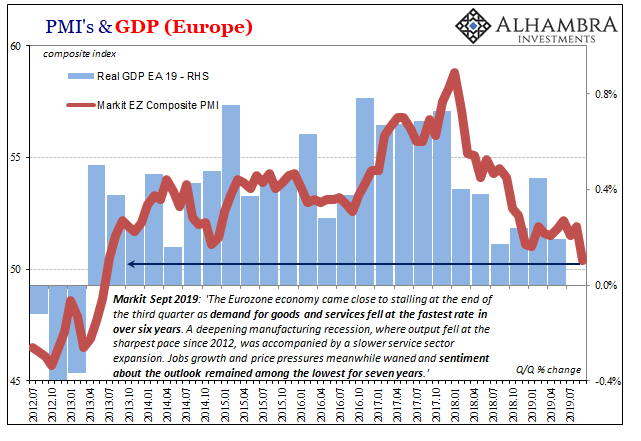

Data like Markit’s composite PMI had put the track of Europe’s economy right square into this no-man’s land between growth and recession. According to IHS Markit’s estimates, the European system slowed down from January to December 2018. Since, it has been stuck near 50 (being the dividing line) but with some margin to spare above it, further fueling these divergent interpretations.

Today, however, Markit put Weidmann and Knot on notice. The group’s composite PMI fell to 50.4 in September 2019 (flash estimate), down sharply from 51.9 in August which had been consistent with that minimal growth level. It was the lowest composite reading in 75 months, more and more looking at least like levels consistent with the 2012 recession.

It’s not just manufacturing, though the manufacturing recession in Europe has “somehow” gotten even worse. The index for new orders, the most forward-looking piece, has fallen still further. As Markit’s press release notes:

The Eurozone economy came close to stalling at the end of the third quarter as demand for goods and services fell at the fastest rate in over six years.

And it is Germany which is leading the renewed deceleration and decline. Markit’s composite PMI for the one country fell to 49.1 in September from 51.7 in August. That’s an 83-month low as the PMI for specifically manufacturing dropped to just 41.4 – a 123-month low.

For Europe, it’s beginning to look too much like 2012. For German industry, more like 2009. Altogether, downside risks aplenty and proliferating.

It puts Draghi’s critics on the wrong side of where they should be. You can at least understand their position, up to a certain point. QE has become easy to mock, that’s what almost four years of no success will do. But that then means if you are against it you have to say there’s no need for it because otherwise the toolkit is empty.

You can’t be a European policymaker and simultaneously admit Europe’s economy is in rough shape but also how there’s nothing the ECB can do about it. OK, you don’t like QE, then what? They have no idea what else to do. While Draghi has painted himself into the narrow corner of QE-or-bust, his critics have done even worse by boxing themselves into everything-has-to-be-awesome.

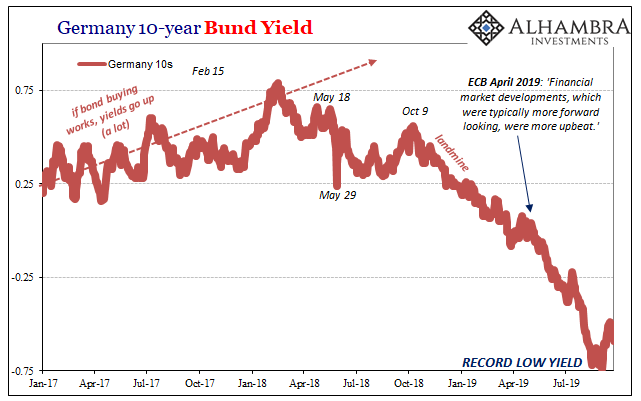

In early September, for the first time going back to last year’s landmine the bond market experienced a hiccup. Bund yields had retraced a substantial amount from record lows. A lot of it had to do with the ECB and the idea that maybe the central bank would put something together which would allow the minimal growth state to continue; for Europe to avoid full-scale recession.

The QE debacle along with recent economic data (and not just Germany) suggests neither. It may already be too late for Europe’s economy, and there’s really never been much these bungling fools can do about it.

Stay In Touch