Shocking, perhaps, but in no way unexpected. IHS Markit didn’t just throw a wrench into all that talk about a global rebound, the organization solidly hammered a substantial nail in its coffin. According the flash estimates for February 2020, the US economy hit a skid.

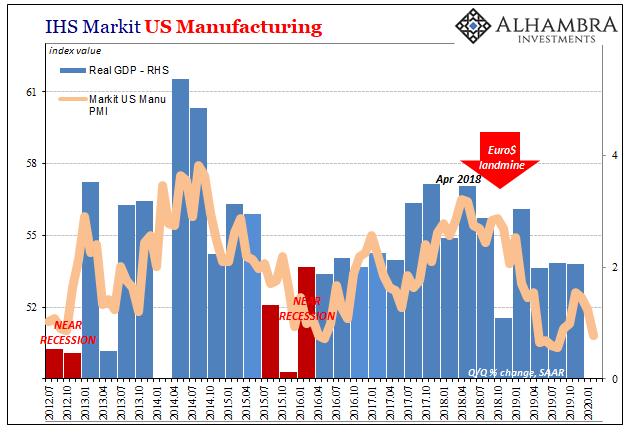

The manufacturing version dropped back to 50.8 from 51.9 in January. The rebound on this side, if you could even call it that, appears to have run its course. It’s now three months in a row for Markit’s index to the downside, and the first time below 51 since last August. This particular PMI had been the leading contributor to the more optimistic global tone.

While manufacturing wasn’t pretty, it was the all-important services sector where the real ugliness showed up. According to these numbers, the US services economy was severely jolted sometime recently. While it wasn’t all that great to begin with (a fact you need to keep in mind), the latest estimates are unusual even by that comparison.

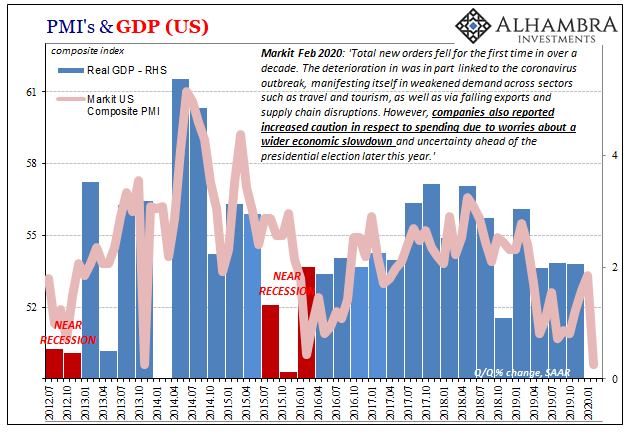

The services PMI fell from a low level of 53.4 in January down to 49.4 for February. It was the lowest in 76 months, dating back to October of 2013. And since October 2013’s low figure was due to non-economic factors, a government shutdown, February 2020’s 49.4 is categorically the worst of these macro indications since 2009 in the series.

Combined, the composite PMI dropped to 49.6, also a 76-month low otherwise meaning realistically the lowest since the Great “Recession.”

As stated at the outset, these numbers may be shocking but they shouldn’t have been surprising. I’m not talking about China’s coronavirus, either. Though that’s the latest buzzword for negative surprises, easily sliding right into the spot which used to be occupied by trade wars, even Markit’s Chief Economist Chris Williamson noted there’s more to it:

Total new orders fell for the first time in over a decade. The deterioration in was in part linked to the coronavirus outbreak, manifesting itself in weakened demand across sectors such as travel and tourism, as well as via falling exports and supply chain disruptions. However, companies also reported increased caution in respect to spending due to worries about a wider economic slowdown and uncertainty ahead of the presidential election later this year. [emphasis added]

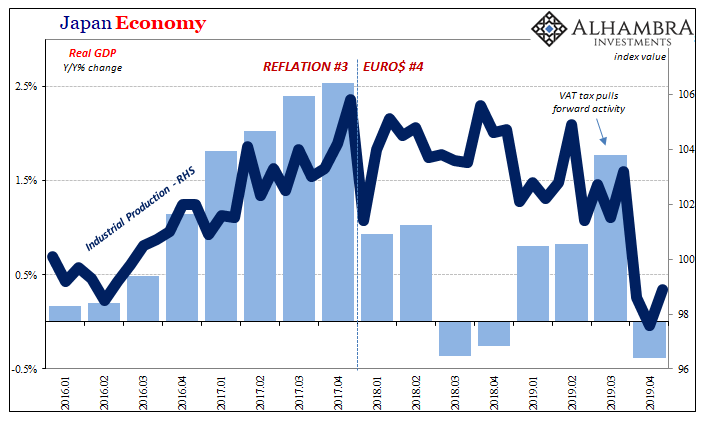

That “wider economic slowdown” isn’t something new. It has surpassed two years long. The reason why this possible US economy stumble should have been expected is that we’d already seen it happen in Europe and Japan.

As noted repeatedly over recent weeks, in those places contrary to the narrative of a global rebound it instead appeared that 2019 ended badly. Very badly.

They’ve both been leading indicators for the economic side of Euro$ #4, the still growing damage from the headwinds and squeeze created by the disinflationary pressures of number four’s still very much alive global dollar shortage. If Europe and Japan tanked in Q4, before the coronavirus, mind you, the US economy was already in danger of suffering the same fate.

Globally synchronized is still the operative term. And since 2017 is so far in the rearview, it isn’t growth which follows it.

Markit is the first so-called soft data to suggest that the US economy might have been caught up in the same downdraft which snagged Europe and Japan. This is, obviously, consistent with the behavior of the bond market – both over the last six months as well as more recently.

With curves pretty much back to where they were in late August, it’s important to note the economic risks of a coronavirus spillover but more than that how such a thing would be just another headwind added to a large and growing force of them predating the virus and trade wars by quite a lot.

We want to be very clear about why this is materializing, not just what could come from it, because we sure don’t need another subprime mortgage excuse. Or Greek debt. Oil supply glut, etc.

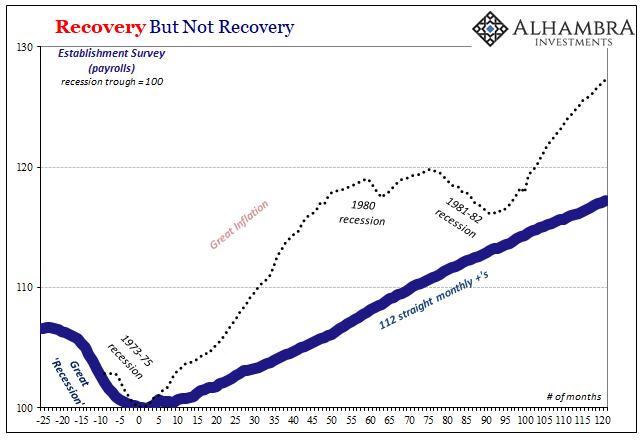

In other words, I’m pretty tired of these Euro$ squeezes and cycles, and I’d sure like to avoid a Euro$ #5 – no matter what happens yet for the rest of #4. The only way we do that is, this time for the first time, we actually nail the cause.

It wasn’t trade wars and it won’t be the coronavirus. If either of those make their way into the official, public convention, especially if number four leads to an outright recession, then number five it will be.

We’ve yet to recover from number one. A nastier number four just makes the probably inevitable number five that much more troubling.

Stay In Touch