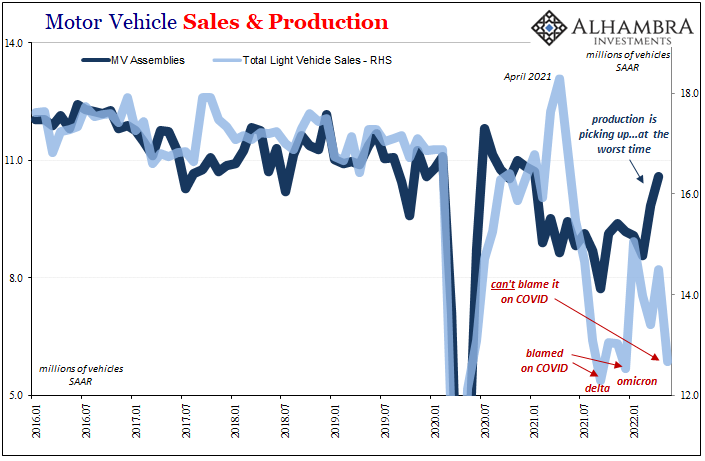

It wasn’t exactly a secret, though the raw data doesn’t ever tell you why something might’ve changed in it. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, confirmed by industry sources, US new car sales absolutely tanked in May 2022. At a seasonally-adjusted annual rate of 12.7 million, it was a quarter fewer than sales put down in May 2021 and 13% below the not-great level from the month prior in April 2022.

Such puny results have typically been reserved for those heavily diseased months of whichever COVID variant or wave, except there was no new coronavirus-inspire disruption this time. Buyers appear to have disappeared, gone on strike for other reasons than the usual 2020 stuff.

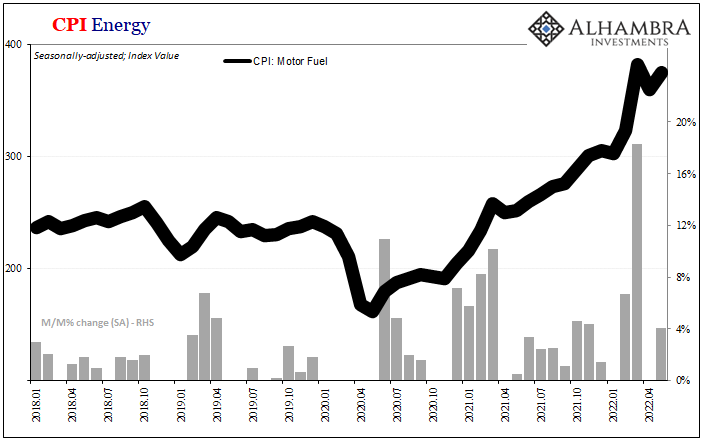

The list of suspects for any strike was always thin. First up, gasoline prices. Americans or anybody won’t buy a ton more new cars when the costs of operation rise as much as they have.

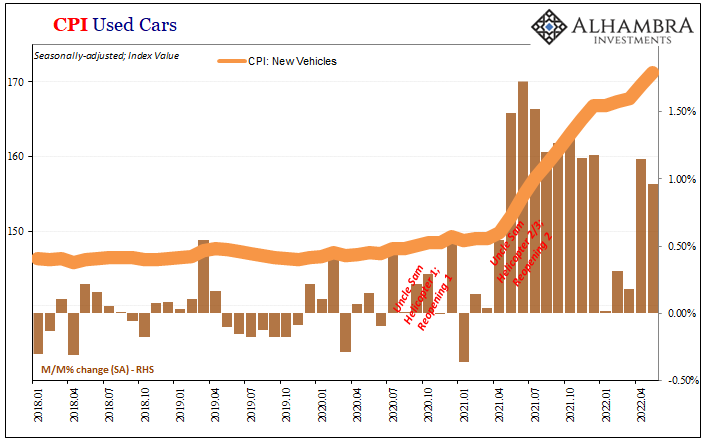

More than costs of operation, we first have to consider cost of acquisition. Carmakers have been able to get away with raising vehicle prices for over a year because demand outstripped supply. Over the past few months, though, anecdotes coming in have added to data like this to indicate the economic (small “e”) imbalance in favor of producers just might have flipped.

Target and Walmart have already said as much across their much wider domains, and these car sale figures extend the warning into the car industry. Today, the BLS shows us that, yes, car prices rose sharply in May. The CPI Index for new vehicles was up another 1% m/m, continuing the same trend from last year.

The supply of vehicles seems to have increased (Fed estimates from IP), prices sticking to trend, so what’s changed is likely to have been demand. Did auto producers finally go too far with prices? That’s the takeaway across much of the consumer space of late.

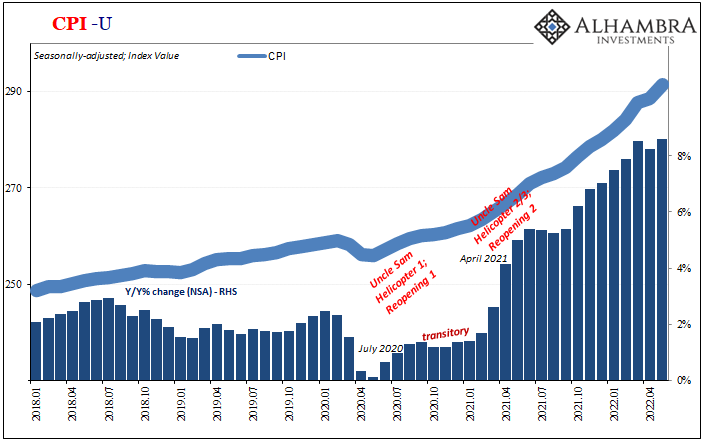

Everything else in the CPI goes along. The BLS added another full percent to the overall index April to May, bringing the annual “inflation” rate up to 8.6% and another 40-plus year high. Where is it coming from?

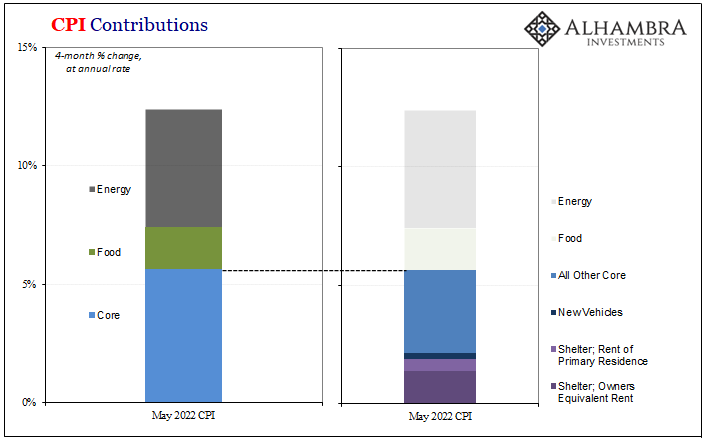

If we look at just this year, since January, it is primarily energy meaning gasoline. The headline CPI in just these latest four months through May has accelerated to a 12.4% annual rate of increase, and we know the FOMC staff does this kind of breakdown math on the regular (thus, ST yields today, which I’ll get to later on).

Of that 12.4% annual rate, a whopping 40% of it, meaning 5 out of the 12.4 pts, was due to heavy price contributions from the energy sector (a third, meaning 4 out of the 12.4, strictly motor fuel or gasoline). I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a Putin Price Hike™, but that is clearly a big part of the current problem added to last year’s supply shock.

Food contributed 14%, or 1.8 pts, while the rest of the so-called core bucket only 45.5%, or 5.6 out of the 12.4.

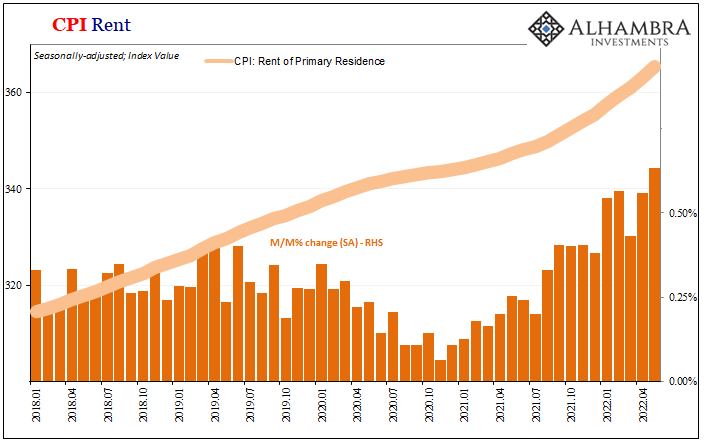

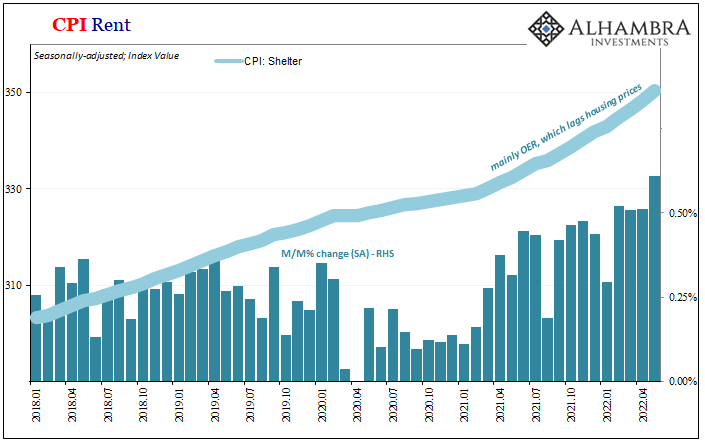

Within the core segment, 42% of it was because of accelerating shelter prices (which made up one-fifth of the headline annual rate). Not strictly rent, however, the accounting fiction which is Owners’ Equivalent Rent (OER).

This is a good news/bad news kind of thing since OER is essentially the BLS trying to extract rent from “comparable” prices of homes occupied by owners rather than rented, a notoriously difficult statistical enterprise that creates serious lags in that extraction process. Long story short, rising OER of late is the lagged response to home price acceleration of the past few years.

And that means, given the way the real estate market is leaning (crashing might be too strong a term here), shelter price increases in the CPI bucket are becoming self-extinguishing. Big contributions today and the next few months, smaller toward the future.

That’s the good news, though obviously the bad news is, well, real estate.

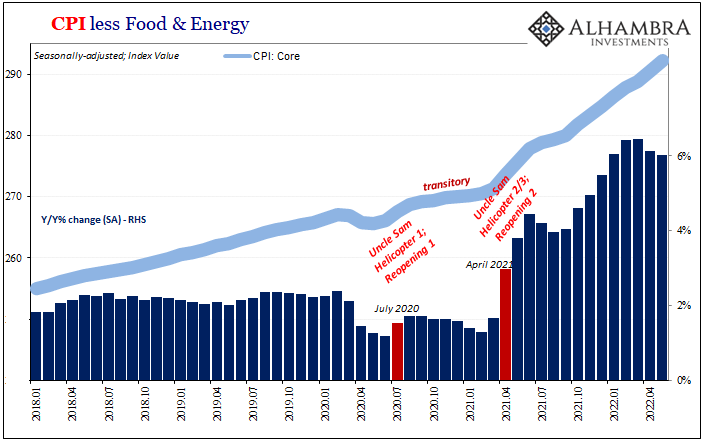

It still leaves quite some room for everything else, the leftovers across the rest of the core bucket. All that added in 3.5 pts of the 12.4 annual rate February through May (inclusive), and that’s where Target and all the other retailers who are finding themselves in the same inventory bucket, pun intended, will begin to have an effect going forward.

Price slashing and almost certainly liquidation sales.

Raw CPI terms, which is what we’re all about here, not only would those 3.5 pts disappear, it’s very probable falling prices contribute negative to reducing the CPI from that segment over the months ahead.

Not much can or will be done about gasoline, at least not until overall global demand for energy shifts even more than it might have already. With global supplies absurdly tight and about to get tighter with the Europeans cutting themselves off from most Russian sources (in principle; how much oil might be sold first to intermediary countries and then resold into less “attentive” parts of the European energy marketplace remains to be seen), it may be until well into recession before that happens (see: 2008).

In this short-run examination, it really has been all energy – had gasoline merely stayed at January levels, already near records, the CPI would have been substantially less with the prospects for further slowing ahead. Of the remaining pieces in the index, there’s much to already suggest “inflation” rates will come down and not by a little over the coming months even if oil isn’t quite ready.

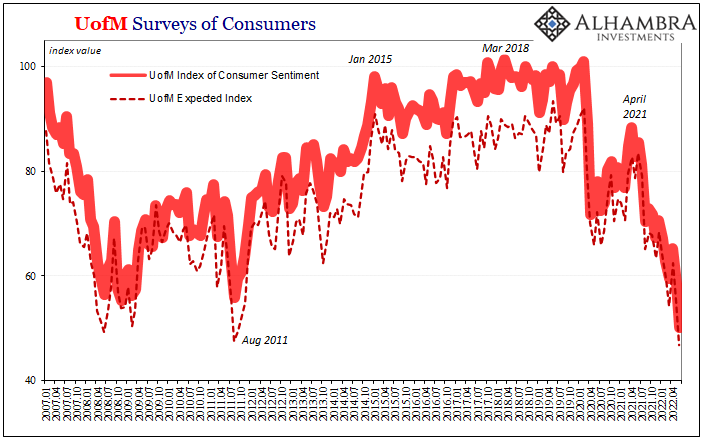

Perhaps most compelling of all is forward-looking consumer expectations; without consumer demand everything is different. The average American right now doesn’t think too highly about the economic climate as they see it. The University of Michigan’s survey of consumers index of sentiment just crashed to a record low.

It is now further down than at any point during the Great “Recession”, that’s how bad consumers are “feeling” at the moment. Reflected in auto sales? Definitely. Other sales and not just those which didn’t happen at Target and Walmart, either.

There is a cumulative misery in sentiment like this which explains why it is worse than 2008 and 2009. Back then there had been at least the prospect for recovery, as bad as everything had gotten even at its blackest point it came to be believed the blackest point was past tense.

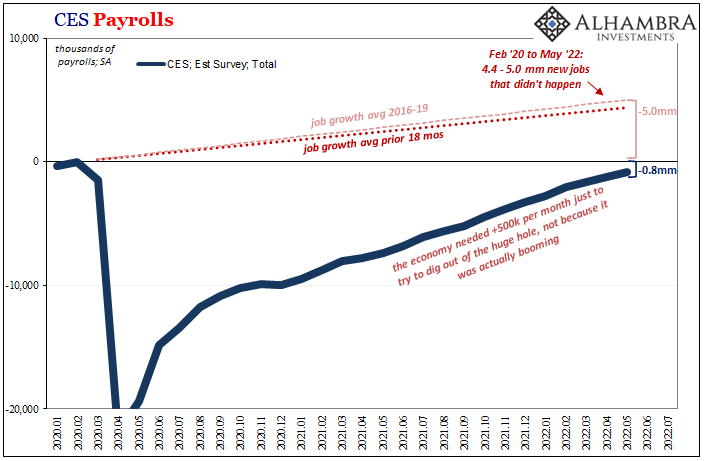

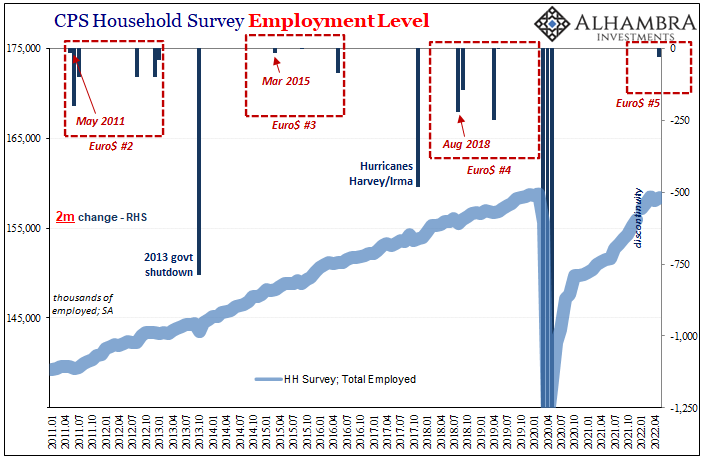

Today, by contrast, the world already seems to have topped out of the 2020 “recovery” which quite clearly was never a recovery (see: jobs). From that low point, now the twin pain of consumer prices unlike in modern memory especially for essentials further combined with basically the world staring into the abyss of yet another recession by which to pile more misery on top (basically the same as summer 2011, only prices faded much faster back then).

And if it the global trend will indeed continue to go on this way, as it has for well over a year, then “inflation” will have solved itself without any need of Jay Powell and the FOMC. This is, you’ll note, another one of those good news/bad news situations.

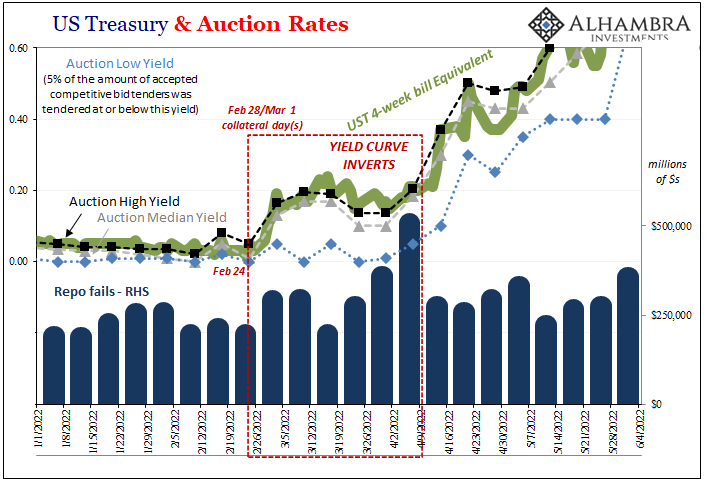

This is why the yield curve inverted months ago and today it is inverted even more so (in the key middle section). The Fed, however, is going to do what it is going to do based on the CPI’s past conditions regardless of onrushing recession risks.

Stay In Touch