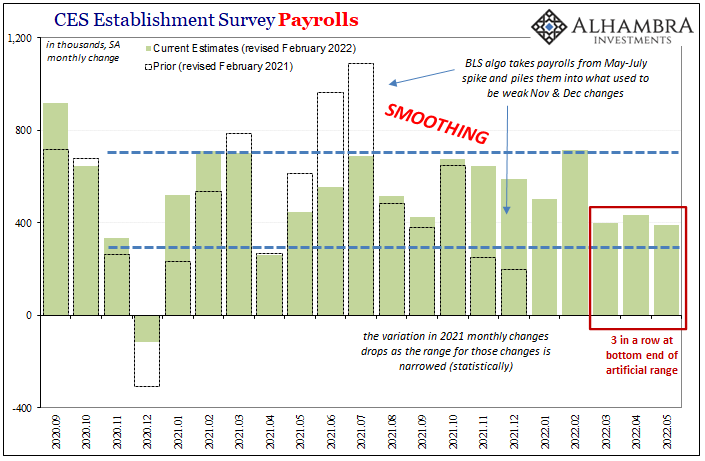

The BLS’s most recent labor market data is, well, troubling. Even the preferred if artificially-smooth Establishment Survey indicates that something has changed since around March. A slowdown at least, leaving more questions than answers (from President Phillips).

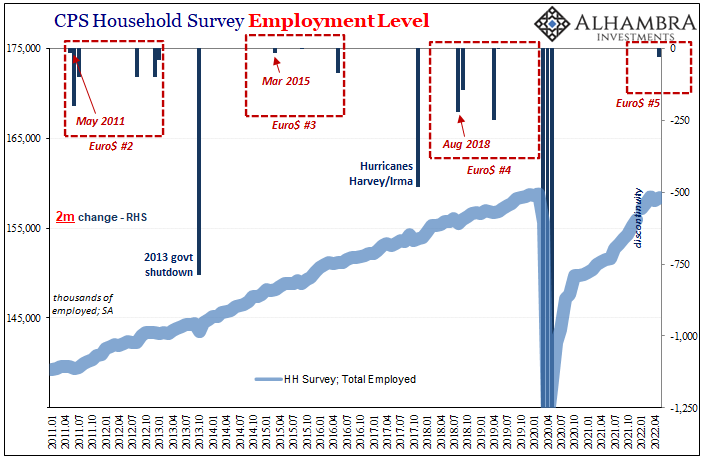

That as much because of the other employment figures, the Household Survey. April and May, in particular, not just a slowdown but a drop in overall employee count. As I pointed out last Friday, a 2-month negative is highly unusual except when the US already experiencing serious weakness, downturn, maybe more.

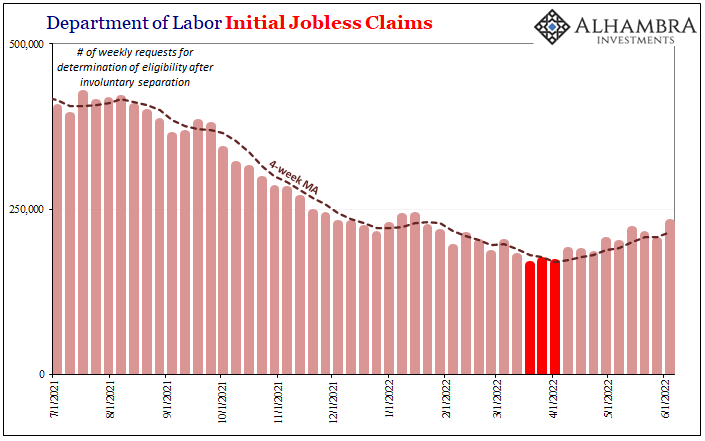

Given these, it might be time to revisit jobless claims and unemployment insurance. Quite unlike the unemployment rate, the number of American workers who are filing for initial verification of involuntary separation so as to claim insurance benefits has been rising…since March and April.

The weekly totals are still extremely low, having dropped to historic lows prior – if only because pretty much the entire American population had exhausted every last benefit. While it might be easy to dismiss claims at less than 250,000 per week, it’s not the level rather the direction and the timing of what may be (so far has been) a hard inflection (especially as it corresponds so closely to other data and more).

It’s the second derivative which stands out here, the clear change in trajectory which so far has lasted several months (ruling out random fluctuation, statistical error, though not yet conclusive). These particular several months:

Rate hikes to blame? Jobless claims bottomed out right about when the FOMC’s first (half) rate action took place. Now that would be some precise timing.

Though the Fed Cult would love to stake Jay Powell’s claim to this, trying desperately to carve the Chairman’s face next to the unearned statue of Volcker, even its members can’t sell this pure coincidence. A single 25 bps rate hike from zero (25bps upper bound) would never, in any universe, cause a rip-roaring inflationary economy operating a max employment to suddenly go into so serious a reverse.

This forces them to choose between presumed rate hike power and admitting the economy isn’t all that great, which would undercut the justification for rate hikes.

The other explanation more and more put forward is the benign-sounding end of “pandemic spending” on the part of consumers. That wouldn’t sell jobless claims let alone Establishment and Household Surveys of softness. It barely counts for what retailers are doing with their ungodly levels of inventory (Target will only be the first).

Besides, below doesn’t sound like Americans shifting their spending habits back toward normal, presuming before 2020 was normal. It sounds exactly like broad-based, economy-harming retrenching:

80% of Americans surveyed plan to change their actions to offset the impact of inflation and rising costs of everyday essentials:

42% are changing how they shop for groceries. This includes opting for cheaper items, avoiding brand names and buying only the essentials.

46% are either dining out less or consciously spending less when dining out.

31% are driving less to offset the soaring cost of gas.

23% are spending less on vacations or canceling them altogether.

22% are taking measures such as canceling subscriptions to the gym, cable, etc.

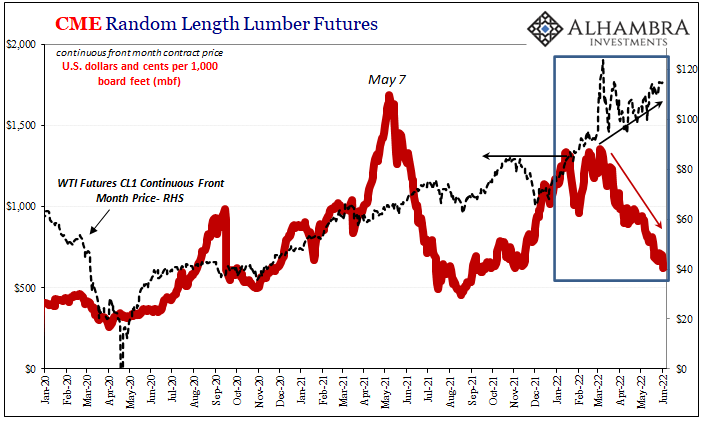

This BMO/Harris survey from the end of May, like jobless claims, pictures a serious amount of distress which can be more closely associated with gasoline meaning oil prices finally going a step (or two) too far. When? March.

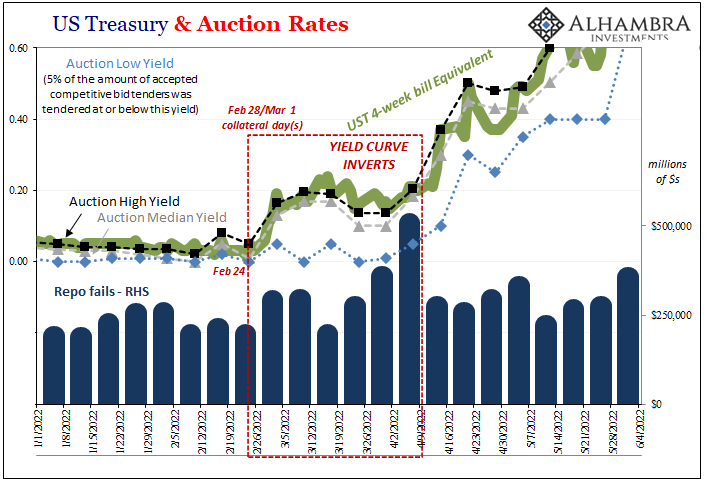

Remember March was also the month filled with the major financial fireworks, Treasury curve inversion to go with ridiculously low T-bill rates meaning monetary tightening in a very real sense the Fed’s rate hikes can only jealously envy. It all went down in March, which now seems to mean jobless claims going up.

Rather than the FOMC, the markets just may have nailed the economy’s (and it’s more than just this, remember Target and Walmart, applying far wider to more than just America) transition from weak but still reopening rebound to, perhaps, more squarely recession dynamics. It sure seems so to this point.

Confirmation, of course, still required and pending.

While any honest inquiry will take that possibility very seriously, the politics of rate hike theater will continue without doing so for the foreseeable future, for as long as possible (repeating the same pattern like policy cycles of the recent past). Yet, even that future is in doubt, markets very much trying to judge just how bad it might get before the theater closes its run for lack of audience.

Unfortunately for Jay, more so the world, it all continues to add up. And the math just isn’t inflationary. Never was.

Stay In Touch