The Federal Reserve has indicated that it will now pause – for a second time, supposedly. Remember the first: after raising its benchmark rates apparatus in December while still talking about an inflationary growth acceleration requiring still more hikes, in a matter of weeks that was transformed into a temporary suspension of them. Expecting the easy disappearance of “transitory” factors, that Fed pause was to be followed by the second half rebound and eventual if careful resumption of the prior plan.

But instead of renewing the “tightening” trend for monetary policy, poor Jay Powell has to try to explain now three rate cuts where that was supposed to have been. Even the most optimistic among you will have to ask what has happened to the unmistakable second half rebound which was going to right the economic ship and put everything back on track (including and especially the BOND ROUT!!!)

At first, back at the end of July, the rate cuts were going to be one and done. Then just the two even though the second one was stepped all over by whatever it was in the repo market (still no one will say). And now three.

It wasn’t ever going to be a series of rate cuts, but now that it is Mr. Powell says it will only be a short series. Three’s the magic number in the constantly changing forecast, the lucky charm. At three, it’s allegedly still the “mid-cycle adjustment” to make sure the strong economy of this record economic expansion continues without interruption.

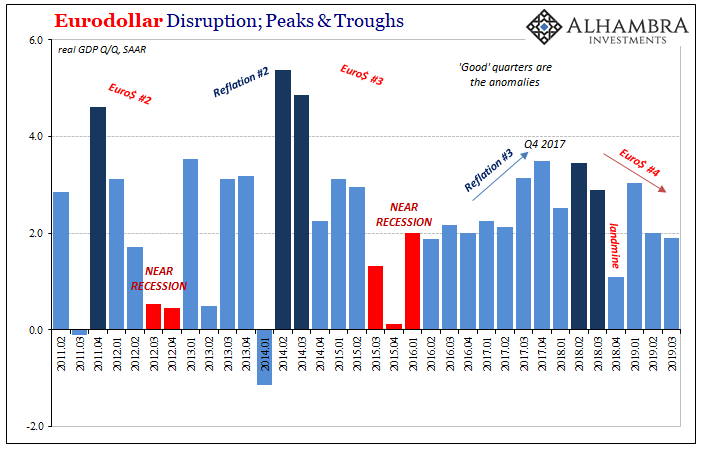

Today’s GDP report from the BEA pretty well demonstrates the fallacies spread among all those claims. Headline growth in Q3 was just a little better than 1.90% (continuously compounded annual rate) following a revised 1.99% rate in Q2. That’s now two consecutive quarters at right around 2% which, if you listen closely, even US central bankers will tell you is the US economy’s post-crisis long run potential (R* and all that).

That’s the part they left out of 2017 and 2018’s “boom”; that one quarter of 4% growth (Q2 2018, which has since been revised to well below 4%) was an anomaly even in the conventional conception. And it probably wasn’t what the vast majority of the public was thinking when most people kept hearing about this boom.

One quarter of close to 4% and that’s it?

So, the FOMC has to consider as a best case that what’s happening in 2019 is the economy reverting to its much, much lower mean potential. Around 2%. In that scenario, mid-cycle adjustment sounds about right (while at the same time appearing totally inconsistent when you also keep hearing about the “strong labor market”).

Forget for a moment how in 2019 the Federal Reserve Chairman can’t ever get his story straight. FOMC policymakers no doubt believe that each successive rate cut will end up being the last; only to be disappointed with what happens next. It isn’t a rebound, and more and more there’s data to suggest it might not be mean reversion, either.

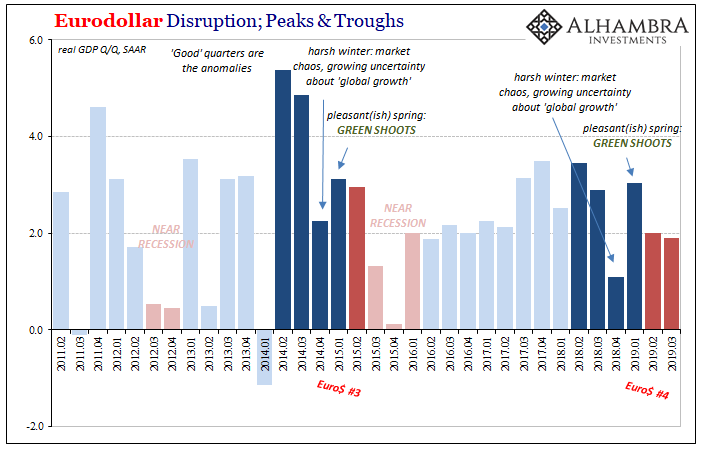

The warning signs proliferate suggesting that the 2% the past two quarters could be just the interim before much lower growth and possibly, if things continue to go wrong, negative numbers. The pattern has already been established where perhaps the base case is another near recession rather than reverting to potential. Q1’s “green shoots” never made it out of Q1, therefore the first Fed pause was DOA.

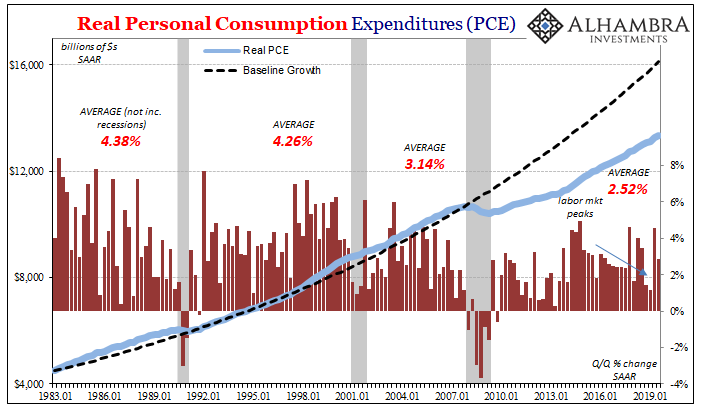

We can start with the plus side; or, what counts as the positives in this day and age of booms that never boom. Consumer spending. In the parlance of the BEA, Real Personal Consumption Expenditures.

This is what Jay Powell will keep pointing to as the base strength underlying. The labor market is awesome which is why, he claims, consumers are holding up relatively well. But are they?

With PCE growth slowing ever since 2014, consumer spending has been at best noisy in recent quarters (the entirety of the “boom”). Q2 2019 over Q1 was better than 4.6% growth, followed by Q3 over Q2 which was just 2.9%. A little better than average.

The good news is that consumer spending hasn’t completely fallen off? It’s not quite the same when you put it that way (the bond market view). And that’s especially true considering that PCE is more of a lagging indication. Other things in the economy typically happen first.

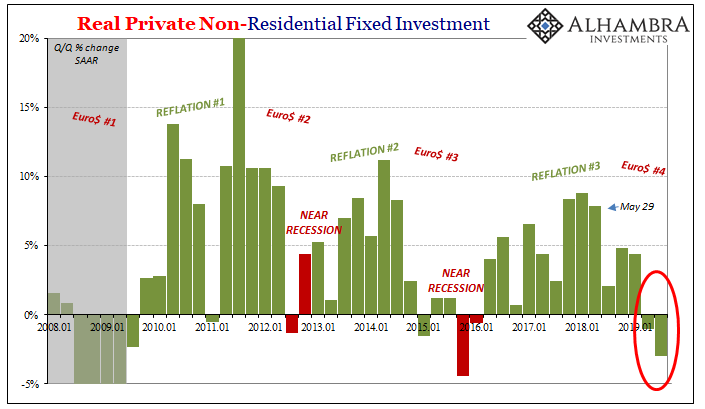

Primary among them is capex, or business investment. The BEA calls it Real Private Nonresidential Fixed Investment. You better believe this is the part which has kept the rate cuts in play to now a series totaling three.

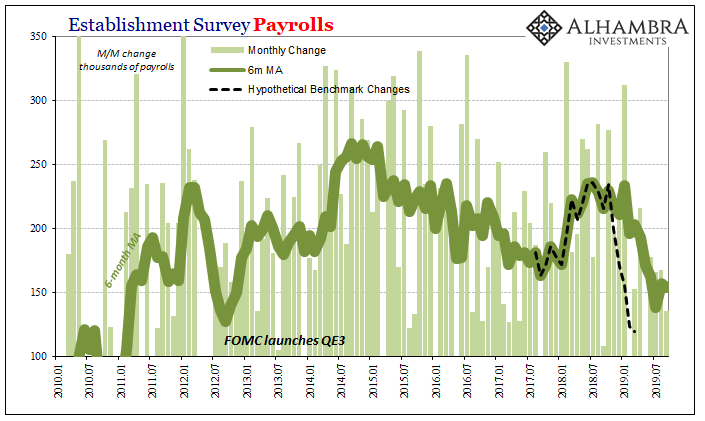

As more of a forward-looking indication of what businesses are thinking (because they are already doing), two straight quarters of accelerating contractions are high on the list of negative signals. The real downside danger, one that Powell and his crew know, is that cutting back on capex could quite possibly lead businesses to also begin cutting back on labor.

They’ve already cut way back on hiring. If it does progress to something more than a hiring freeze, there goes whatever was left of consumer spending – strong today or not.

In other words, the economy is coming along in exactly the way it has during the past eurodollar cycles. What may be different this time is the depth and duration of what more and more looks to be a downturn. Does it get to the same level of near recession, like 2015-16, and then stop? Does it go further into something more like 2009 (even if that kind of recession never gets to be “great”)?

We don’t know the answers to those questions, obviously. What we do know is that the risks are growing and, given the employment numbers, may be as high as they have been in a decade (also the bond market view).

The rate cuts are the FOMC’s backwards way of acknowledging reality in 2019. The upside is gone; dead. The best we might hope for is, again, mean reversion (2%! hooray?) There is now only downside. Because of that, we don’t yet know where the rate cuts, or the economy, will stop.

And that’s why the “bond market” is betting on more from Powell no matter how many pauses he talks about along the way.

Stay In Touch