One of the biggest intellectual crimes of the Volcker Myth is how it quashed what likely would have been fruitful (in my opinion) further examination into the monetary designs of the actual global reserve system. People today still whisper about some secret oil-soaked deal which saw UST’s end up in the hands of Arabia’s Saudis, as if this was something unusual or earth-shattering. Hardly.

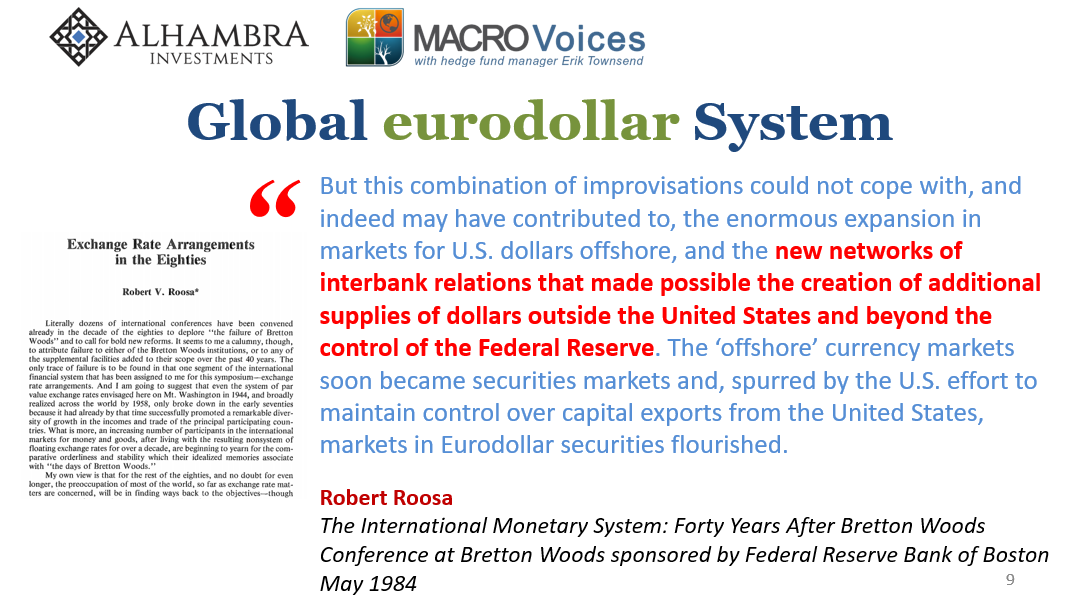

Nixon wouldn’t end the Bretton Woods era, the eurodollar already had long before the President closed the window on US gold convertibility. Prior to the Volcker (mis)adventure, while far from widespread the conversion into a eurodollar operation was at least recognized and far from the pervasive silence of today this was openly discussed and investigated.

One such instance was right in front of the United States Congress. In February 1977, the Joint Economic Committee, a combined House-Senate effort at the time increasingly interested in getting some answers for that whole Great Inflation thing-y neither the Treasury nor the Federal Reserve (or any Keynesian Economists) could explain, let alone bring to a halt, its members heard the testimony of one Dr. John R. Karlik on the subject of the “eurodollar market.”

When it came to oil, there was neither secrecy nor intrigue:

The Eurocurrency market provided a vital service in accepting large deposits from oil producing countries and lending the funds to hard pressed oil importing nations. Developing countries contending with increased energy and food costs and, subsequently, with a drop in earnings for their own commodity exports, have been especially aided by credits obtained in the Eurodollar market.

That some oil producing nations chose to use USTs as a store of value for some of their surplus within the overall eurodollar medium of exchange framework merely the simple byproduct of this decades-old global monetary arrangement – liquid, safe, and, above everything else, acceptable by the banking system which is where, and what, all the money is.

The very term “petrodollar” is itself a misnomer, a wildly incomplete perspective recognizing only a small portion of a far wider system which didn’t just show up around 1973 (thus, why 2018’s petroyuan introduction, among other things, didn’t come close to being the game-changer too many had tried to claim). On the contrary, eurodollar had already replaced dollar-based gold exchange in the nearly two decades leading up to then, the very reason why the “Eurocurrency market provided a vital service” once OPEC acted driving the price of crude sky-high.

But how had it done this?

I defined the arrangement many years ago as more like a computer network than an immediately familiar currency:

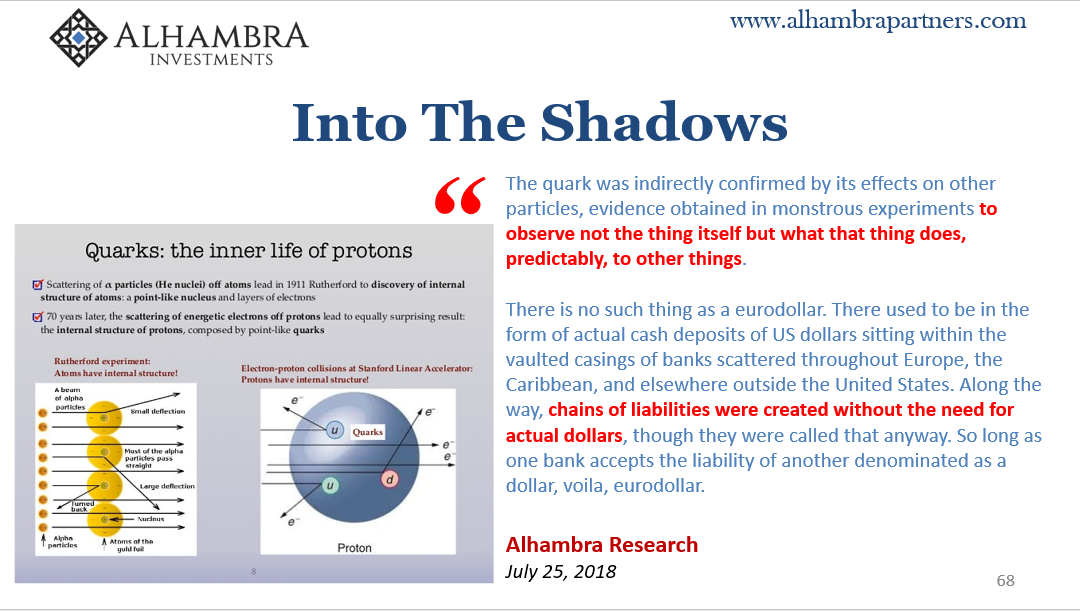

The eurodollar can thus be described as a multi-dimensional series of often parallel but intersecting financial functions all designed to encompass a single, global whole. The nature of those functions just happens to be monetary, so that the end result of eurodollar functionality is monetary or financial. In most simple terms, it solves the basic equation of how to get numbers all over the world to balance and stay balanced. That used to be quite cumbersome and often dramatic, as under the prior currency standard, gold or dollar/sterling, meant taking some accountant(s) down to the vault and performing a physical audit. By removing the dollars from the eurodollar (in reality, there weren’t many in it to begin with) or money from the monetary, the system could perform in unimaginable ways since it would be free to reinvent itself over and over. The standards would remain but the methods and products did not.

This was a portrayal not all that far from what Dr. Karlik had detailed back in ’77. What he told the JEC was:

Thus, an initial dollar deposit in a European bank can lead to a variety of outcomes. The amount of additional liquidity provided to nonbanks may be zero, equivalent to the deposit, or some multiple of the deposit. This uncertainty about who may be the borrower of dollars from a European commercial bank and how these funds will be employed raises the question of the size of the “Eurocurrency multiplier.”

Yet, given such gross uncertainties, Karlik would still go on to say that he couldn’t attribute much or any of the Great Inflation to eurocurrency oversupply, “Therefore, even if one were to accept the thesis that excessive monetary expansion were an important cause of inflation, Eurocurrency markets hardly appear to be a major source of that expansion.”

Now, why would he make such a ridiculous statement? We know, without question, inflation is always and everywhere money. But Karlik, you see, wasn’t just a Senior Economist working for the JEC, he was first a Senior Economist at…the Federal Reserve.

The same “central bank” which had a vested interest in pointing the finger somewhere else, having spent the entire Great Inflation blaming anything and everything except an out-of-control monetary system. Congress in February ’77 had brought in the equivalent of the local fire department battalion chief to explain why an entire city block was burning down on his watch because he dispatched only a single piece of equipment to put out the inferno.

Still, the mechanics of his eurodollar description more closely resembled reality than did the original from the BIS put out way back in 1964 (still nearly a decade late after eurodollars got going). Before then, a few had made the quite understandable inflation potential arising from unrestrained external money growth into legitimate criticism, which, of course, the BIS quickly dismissed.

At the same time certain criticisms have been made of the market, in particular that it hampers efforts to control inflation and that it leads to unsound banking practices which could prove dangerous in the event of a large withdrawal of funds by depositors. So far as inflation is concerned, borrowing in the Euro-market by a country may enable the private sector to circumvent a domestic credit squeeze, or may allow the authorities to delay corrective action against an external deficit.

While admitting some “element of truth”, the report claimed they were “easily exaggerated.”

All those things actually did happen!

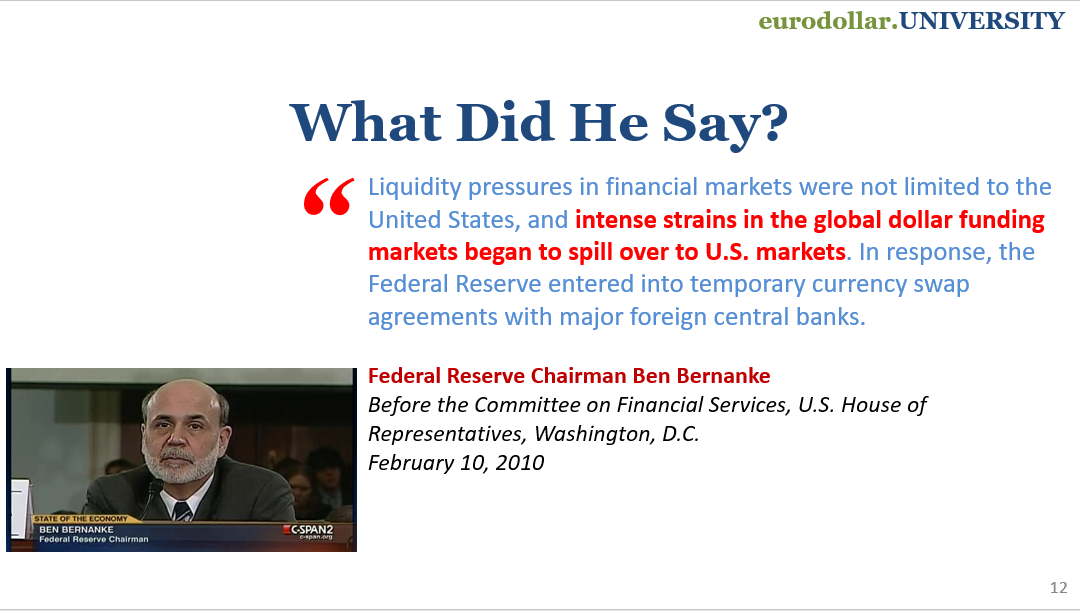

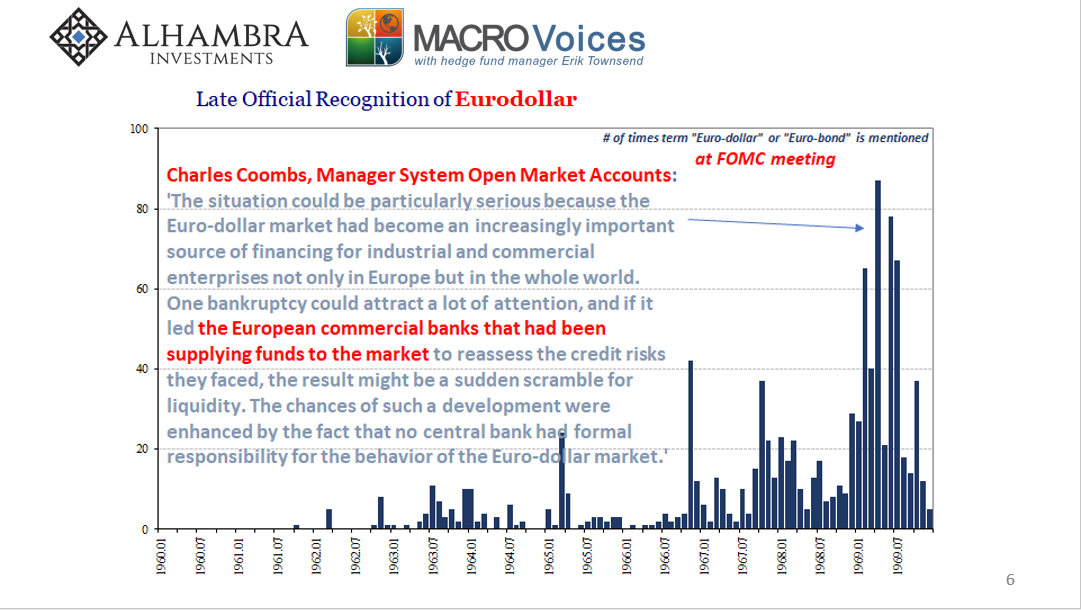

The large withdrawal of funds (not by depositors) was essentially the 2008 “somehow” Global Financial Crisis in a nutshell (don’t just take my word for it, out of the horse’s mouth above). The eurodollar had allowed Italy, in particular, to circumvent its own domestic credit squeeze at the very moment those words were written. The Great Inflation, well, that was just a year away and you’d have to believe in Santa Claus to not believe there wasn’t a connection between the rapid, unrestrained monetary innovation and expansion eurodollars represented and true, unrelenting monetary inflation (that one is for you, Emil).

As to the nature of that inflationary episode, here again the mechanics were described relatively accurately even though their implications got downplayed officially: “…it is claimed that long chains of interbank transactions may result in excessive stretching of the periods for which ultimate borrowers obtain funds as compared with the maturities for which original depositors place them…”

From this understandably rudimentary view, they theorized dollars go in and then get engaged in “long chains of interbank transactions”, meaning balances change hands multiple times between global banks outside the US, before then reaching their ultimate user in the form of a non-bank credit borrower.

You can, I trust, see how the BIS view formed the basis for what then Dr. Karlik would add to it roughly thirteen years later. His testimony admitted to innovations, or series of wrinkles which changed “long chains of interbank transactions”, a sort of linear progression from depositor through several banks to then ultimately arrive as a credit balance for the non-bank borrower, to then multiple potential off-points along the way.

Further, Karlik confesses that, given these potential exit ramps, “…uncertainty about who may be the borrower of dollars from a European commercial bank and how these funds will be employed raises the question of the size of the ‘Eurocurrency multiplier.’” Not just question of size, the whole thing is up in the air.

To put it simply, the BIS version said: a dollar goes in, it changes hands many times one bank to the next, then comes out as a non-bank loan. This is already problematic from a regulatory and control standpoint, yet seems relatively straightforward enough. And if you accepted this description, it really might seem a trivial matter not worth taking too seriously.

It wasn’t taken seriously, which is why a mere few years later officials were forced to even more discussions about the eurodollar (below), or Eurocurrency, system. The very same years when (not) coincidentally the Great Inflation got off to its roaring start.

Coming back around again, the updated ’77 version then says: dollars somehow got in, they change hands many more times than anyone can track, in more ways than any official really understands, and if all that wasn’t enough we have no real idea where or how they might come out. Refreshing for its honesty.

In spite of that, Karlik would spoil it when he went on to say he was quite confident there was no eurodollar connection to the Great Inflation! At least he was consistent in that regard; the Fed’s position at the time was that the inflation was the fault of Treasury.

How might this reluctant mainstream thought progression really have progressed if the Volcker Myth hadn’t intervened?

At some point in the eighties, the always-late Economists and staffers at the Fed just might have been able to put two and two together, to go from long yet relatively simple chains of interbank liabilities to the unknowable multiplier to eventually, “The eurodollar can thus be described as a multi-dimensional series of often parallel but intersecting financial functions all designed to encompass a single, global whole.”

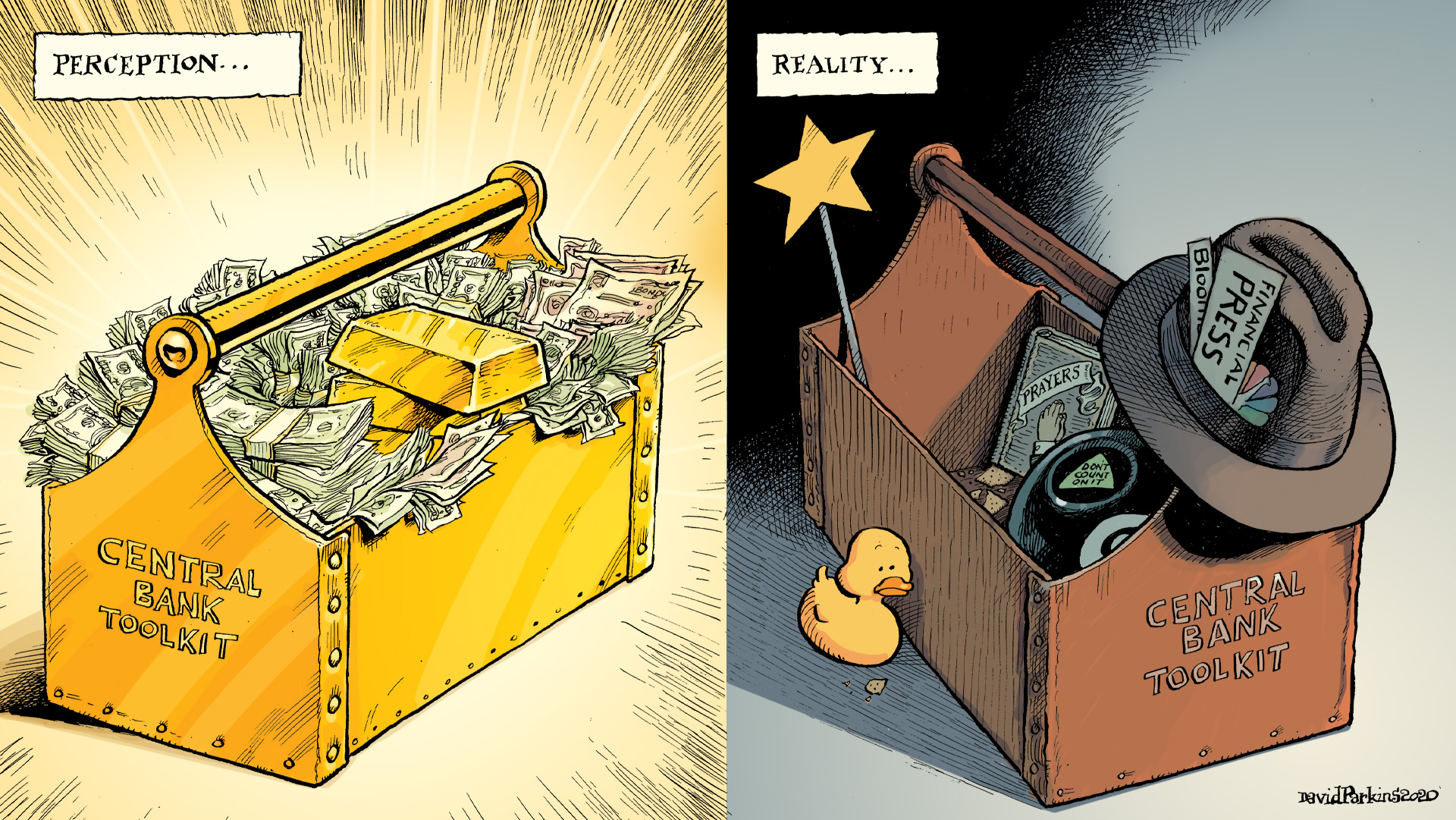

We’ll never know because the essence of the Volcker Myth is that the Federal Reserve was all-powerful and would handle all of the monetary details – even though it had been the Fed which had just proved over a seventeen-year stretch it had no idea what was going on money-wise here let alone outside of here.

Always behind the curve of monetary innovation conducted by banks, what Greenspan would later call the “proliferation of products”, maybe the Economists at the Fed never would have caught up to them. Shouldn’t someone have tried, though? At one time before Volcker, they did.

But hey, that same “maestro” guy would move the federal funds target around by a quarter-point here or there! Sometimes by fifty, when he really felt like making a statement.

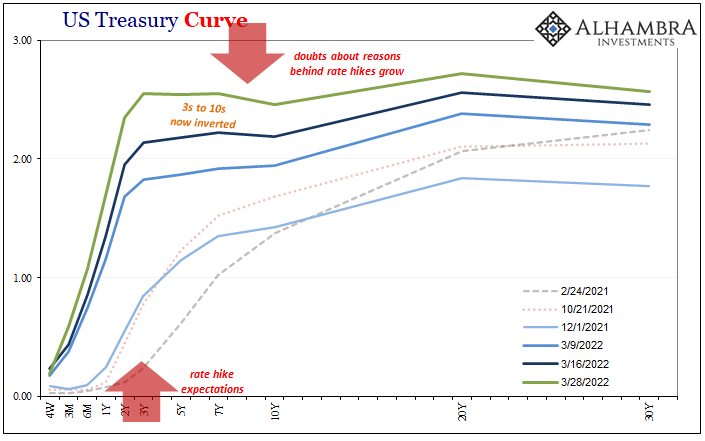

As Janet Yellen would very publicly disclose decades later, the post-Volcker reality is that the communication of intent is the policy, not the mechanical process of monetary intervention. This review reminds us why that is, just in time for markets to more thoroughly outright reject Jay Powell’s own intended statement.

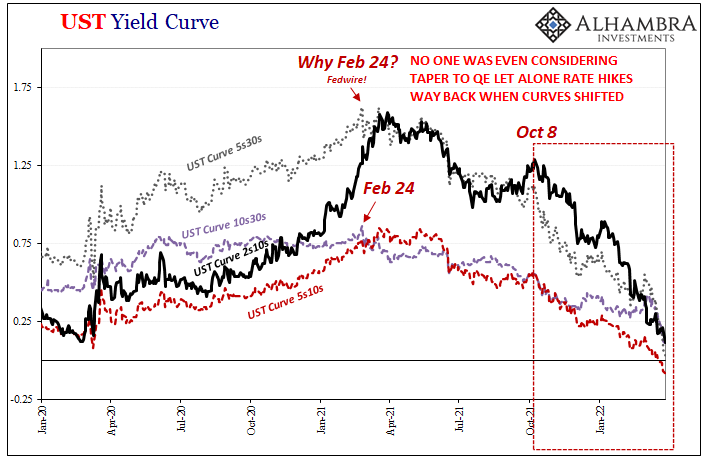

For a brief moment today, the 2-year US Treasury yield was fractionally higher than the yield for the 10-year, and the current FOMC is only a single rate hike in. Once the 2s close above the 10s, the media will be stirred to ask the uncomfortable questions the Fed just doesn’t have answers for. Maybe they would have if not for the ridiculous retelling of the Volcker era.

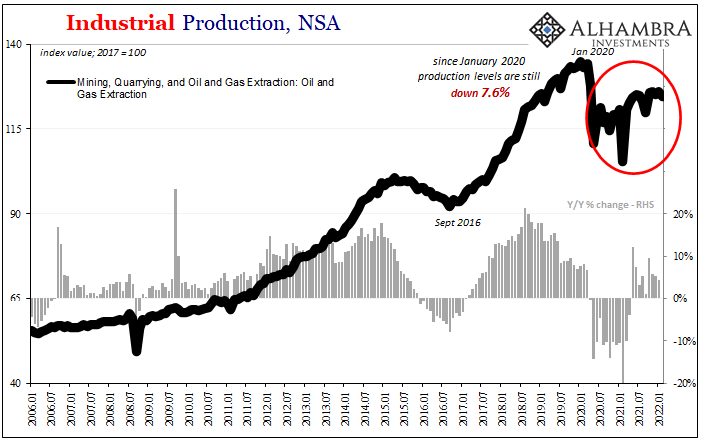

The last little bit of irony has to be oil and how much of a role it might be playing in the unfolding drama, the ratcheting pain of gasoline prices which aren’t actually flying due to inflationary currency, not this time around.

Inversion spreads again, this time the "big one."

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) March 29, 2022

2-year/10-year just crossed intraday. Like before, may not stick into the close but it will over the coming days.

Please explain this one, Mr. Powell.

Even the normally friendly bank Economists are running for cover. pic.twitter.com/Q5dlspL4K1

Stay In Touch