It’s another example of the difficulties in trying to evaluate and analyze non-economic factors. China’s virus outbreak is a nightmare for those unfortunately living through it, and Chinese officials aren’t doing themselves any favors. Trust is a sketchy enough concept.

The WHO today says there is no pandemic, which, as Erik Townsend of MacroVoices points out, immediately puts this announcement at odds with the official WHO definition of one. Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus claimed that COVID-19 is not spreading wildly and that instead of a pandemic, defined as outbreaks in two or more continents, the coronavirus has led to what his group will classify as separate and purportedly isolated instances.

What we are seeing are epidemics in different parts of the world.

Different epidemics, apparently.

I claim no expertise in diseases or virology, so make of it what you will. There is no doubt this is a serious condition, and not for just China, but I also think that it’s being overhyped – though it is hard to know one way or the other.

For example, the WHO also said that (according to Chinese estimates) the number of new cases in China declined sharply today – even as the thing is confirmed to have spread to places like Italy. In China itself, the Communist government announced that it will postpone the National People’s Congress originally scheduled to begin March 5. The rubber stamping will have to wait for another week or maybe a different month altogether.

Not only that, there are persisting reporting issues. Late on this coming Friday, China’s National Bureau of Statistics is slated to release its PMI estimates for the manufacturing and services sectors. They are bound to be ugly. So far, there is no indication that will be delayed – though the whispers of ugliness are proportional to the whispers they won’t be released on time.

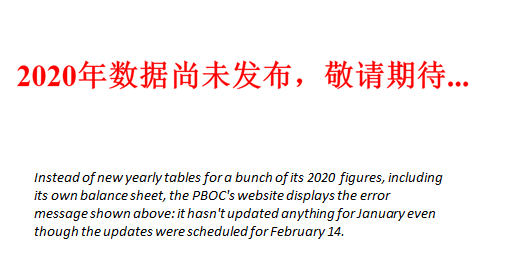

Already, though, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has yet to report its balance sheet figures for January 2020 – even though the advance schedule had set the release for its central bank survey on February 14. Ten days ago. Likewise the depository corporations survey, which had also been planned for the 14th.

These are key numbers – for me they are key in any month – among many who might be interested in trying to gauge the potential economic and financial fallout from COVID-19 by judging how Chinese monetary authorities are responding to it.

On the one hand, you would think that the central bank would want to reassure everyone that policymakers are taking it very seriously and responding forcefully; on the other, by confirming a forceful response it could simply confirm everyone’s worst fears.

In short, a huge helping of uncertainty. We can’t know the economic fallout, it’s too soon to judge the spread, and there is nothing but conspiracy theories and wild speculation in the absence of forthright and timely information.

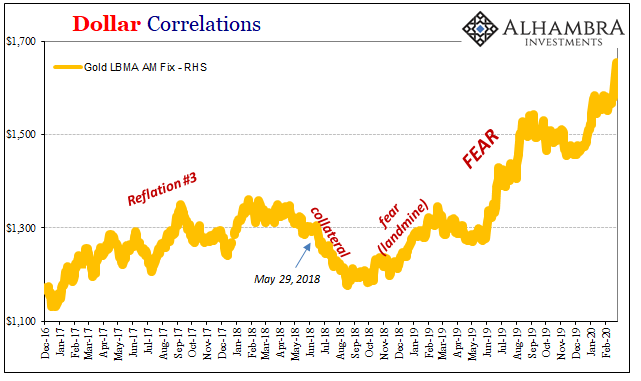

Small wonder gold has skyrocketed. The world’s end-of-the-world insurance being bid just in time for start of the long-rumored zombie apocalypse.

That may be (some of) the hype, but there are also legitimate reasons for the more recent amplification in fear-gold pricing. And not just the uncertainty related to COVID-19. In fact, when you look at how gold has behaved over the past year, year and a quarter, it’s pretty clear the more basic correlation underlying.

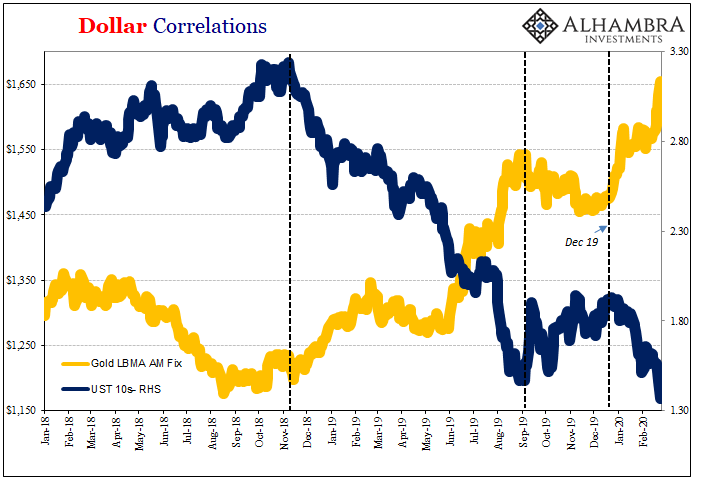

At times like these, gold is strongly, inversely related to Treasury yields. In the conventional sense, gold is talked about as an inflation hedge. History proves that it is a poor one. That’s not what gold truly protects against, as I wrote the last time the curves all looked the way they do today:

Just as in the bond market, the gold market knows central banks are, outside of sentiment, powerless (moneyless monetary policy). That’s why as gold moves higher inflation expectations – especially longer run expectations – have cratered. Bonds as gold know what’s coming from officials, and yet both are discounting monetary policies because all the evidence says that no matter how big the talk monetary policies are only that.

Like 2008, the big error isn’t the Fed going way too far with stimulus, the big error is in thinking anything the Fed does is stimulus. And that’s precisely the backdrop and predicate condition for serious instability. We know what happens when liquidity turns sour without any effective backstop at all because unlike the mainstream media these markets haven’t the luxury of looking the other way and taking the word of Fed Chairs at face value.

Or PBOC Governors.

In other words, as Treasury or bund yields plummet (again) they take inflation expectations down with them. Supposedly that would be gold negative, at least according to the mainstream convention. Yet, the more yields fall the more gold goes up.

Both markets are saying something, the same thing, about monetary policies, economic risks, and broad uncertainty. It’s not inflation.

And it may not be the coronavirus, either, at least not specifically that. For one thing, gold’s trend has been rising (like the dollar) and yields falling for far, far longer than this pandemic. More indicative of the still-ravaging Euro$ #4 virus than anything else (especially trade wars).

Even in its most recent breakout, fear gold predates common knowledge of the China pandemic by several weeks. Maybe someone out there had advance warning of what was already going on inside the infected areas before it hit the mainstream news – and began hedging against it.

More likely, in my view, Treasuries as gold were betting on renewed economic and monetary risks regardless of COVID-19. After all, as we can plainly see now, the global economy maybe struck a second landmine at the end of 2019 like it had at the end of 2018. Last year did not finish well at all, especially in those key bellwether places that have repeatedly confirmed their bellwether status the past couple of years.

While I pause to make too much of it, I also don’t want to make too little, either. What I’m saying is that the market isn’t just trading on virus news. In the sense that it might be, that’s only because whatever economic problems could potentially arise from the outbreak they will be added to a situation that is and was already troubling to begin with.

Another headwind to add to the existing tempest. Therefore, should fears of the pandemic’s reach prove overwrought, it shouldn’t come as a surprise if overall markets treat that possibility the same way they’ve traded (read: forgotten) trade deals.

Stay In Touch