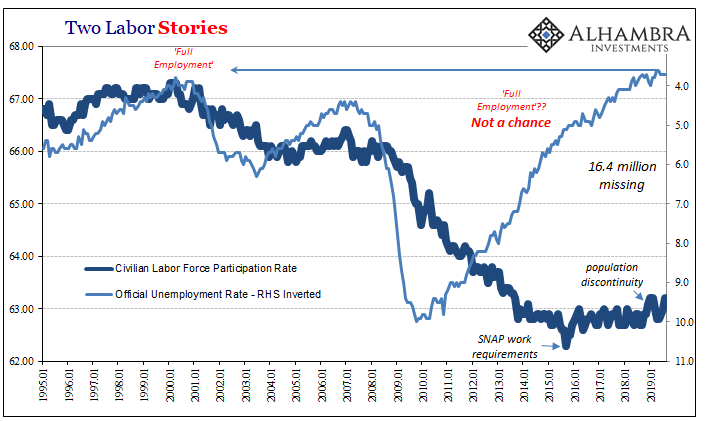

It wasn’t just the unemployment rate which was one of the key reasons why Economists and central bankers (redundant) felt confident enough to inspire 2017’s inflation hysteria. There was actually another piece to it, a bigger piece potentially complimentary and corroborative bit of conjecture. I write “conjecture” because despite how all this is presented in the media there’s very little precision to any of it.

In many ways, if you pay close enough attention you can actually see how they are just making things up as they go. We all tend to do that from time to time, of course, not always sure how to interpret data and being left to our imaginations, but Economists trying to behave like actual scientists aren’t supposed to make blind stabs in the dark, to fit data to suit their emotional needs.

It’s one thing to look at the evidence and be unsure what it is telling you; quite another to use that uncertainty as the only way to make your case.

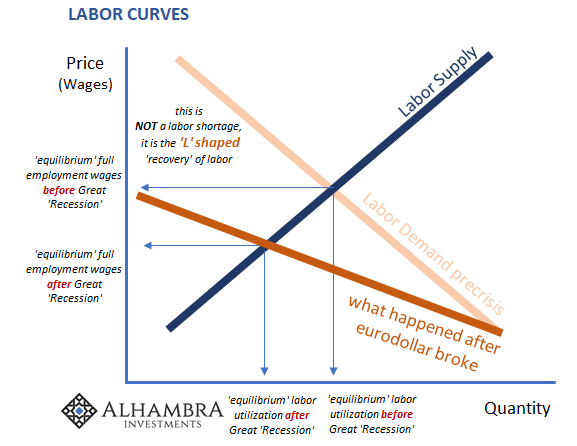

Having been removed from the inflation and its hysteria for some time now, more than a year, really, it’s worth reciting the expectation one more time: acceleration of growth leads to a shortage of workers forcing companies to bid for scarce labor while at the same time passing along those increasing costs to consumers in the form of price inflation. The lower the unemployment rate, the smaller the pool of available labor, the more prices will accelerate.

Slack.

But macro slack is actually a multi-layered concept. It doesn’t just apply to the jobs market, and it isn’t completely defined by the unemployment rate (obviously, given how the last few years unfolded). There’s also broader economic slack to consider, as well.

If Economists define labor market slack in terms of the Phillips Curve, or some fancier modern version of it, they use the “output gap” to explain broad macro slack.

In general terms, the output gap is simply how far below economic potential the economy is running at any given time. “Potential” in mainstream terms is typically defined by some form of NAIRU concept, or non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. It is how much growth the economy can “tolerate” before it starts to become inflationary.

How much overall slack defined by demand.

During recession, there’s obviously quite a bit. That’s one big reason why no one expects accelerating inflation during cyclical downturns. As businesses scale back, there is spare capacity everywhere. Central bankers therefore are given a free hand at “stimulus” because so much economic slack means it will be quite some time before monetary “accommodation” might become problematic.

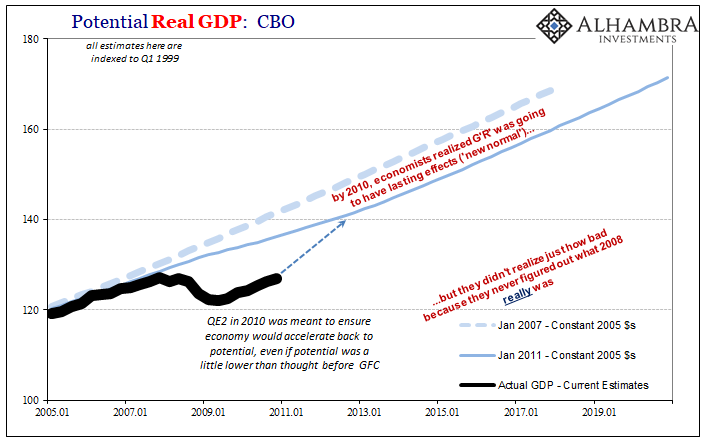

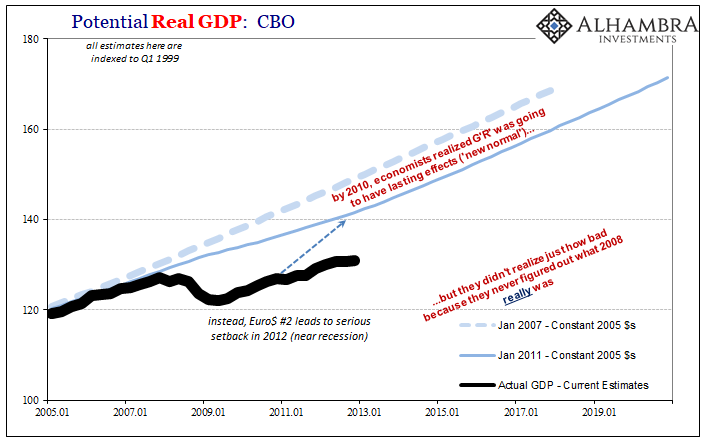

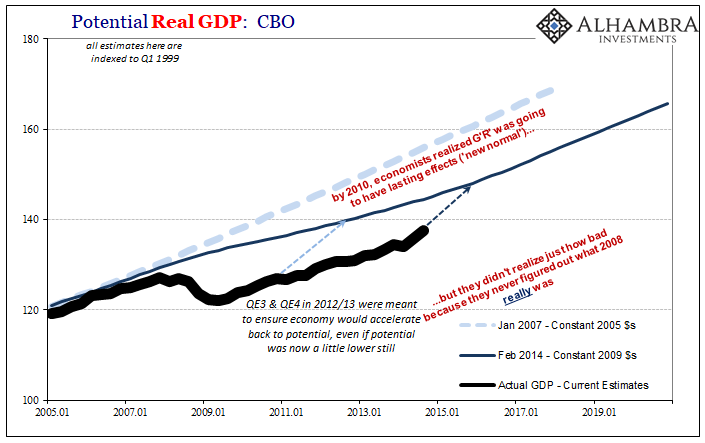

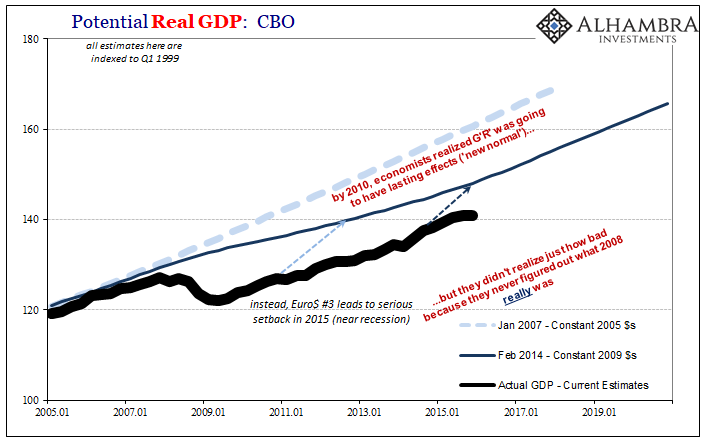

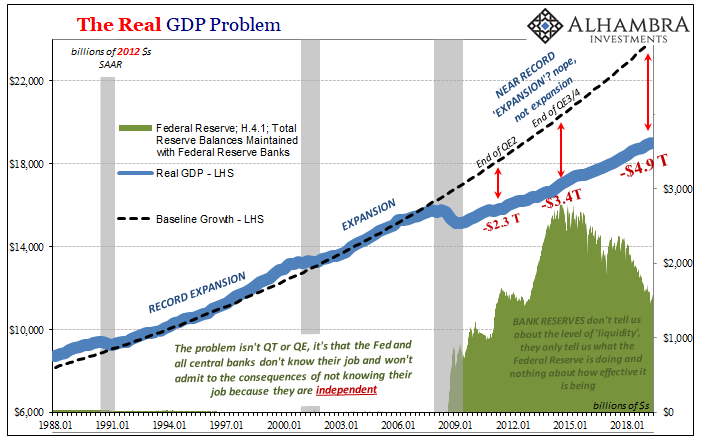

It wasn’t ever supposed to take years and years before the US economy reached that point. As noted yesterday, by every expectation, even acknowledging the “new normal” aftermath of the Great “Recession”, Economists and policymakers (redundant) had believed that even if it took longer than usual given a cyclical downturn of that size within a few years slack would be used up and the system fully rebounded to its potential – even if potential was a little less for reasons no one quite could be sure of.

But that never happened; instead, the US economy kept underperforming at each and every crucial juncture. Where full recovery was supposed to show up, meaning a return to potential, “unexpected” downturn would develop instead. Ben Bernanke’s false dawn(s).

Two of them so far, meaning not likely just random bad luck.

This is the main point for everything. Was the economy being consistently held back from potential by some dark, powerfully negative influence yet to be identified? Or was economic potential itself reduced? Officially, it can only be the latter.

Economists believe they know everything worth knowing therefore to them there was no possible way some unknown, unaccounted for shadowy force could be responsible for what would add up to the entire discipline’s greatest combined failure – the very fact 2008 happened in the first place and how its effects have never been confronted, leaving the whole world to spin faster under more and more dangerous conditions.

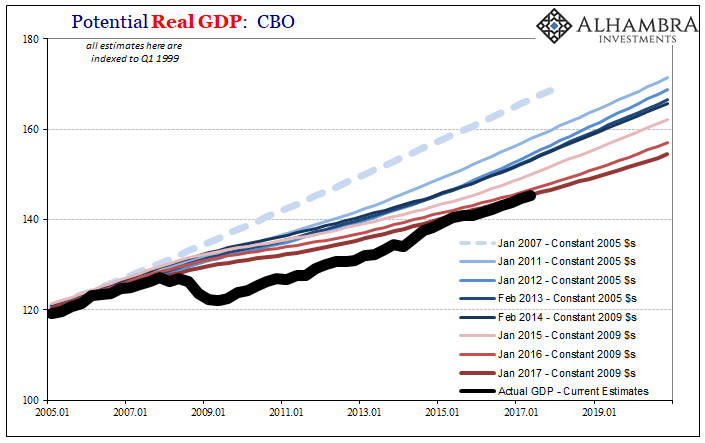

Time and again, they opted to revise their ideas of potential so as to avoid having to ponder that very uncomfortable possibility.

This is where R* begins to show up. You can’t just rewrite total economic potential without some explanation for it. Thus, Economists have asked us to believe that quite randomly around 2008 Baby Boomers started to retire in massive numbers, rural American enclaves all at once discovered fentanyl, and those dispossessed (laid off) by the huge swell of macro slack due to the Great “Recession” simply decided they’d rather never work again than go back to school and learn to code.

It sounds ridiculous because it is ridiculous; and all with one purpose in mind, to avoid having to admit there might actually be macro slack in the economy. They all say if the economy hasn’t performed better it must have been because it couldn’t.

If there is macro slack, then guess what? Economists have gotten the last decade wrong. The economy could have performed better, maybe even far better. The ongoing presence of slack undermines their entire thesis, that they did all the right things and required only enough time to show it.

Now you can understand why the hysteria in late 2017. It was as much cheerleading as analysis; hope and fingers crossed rather than an honest interpretation of good data.

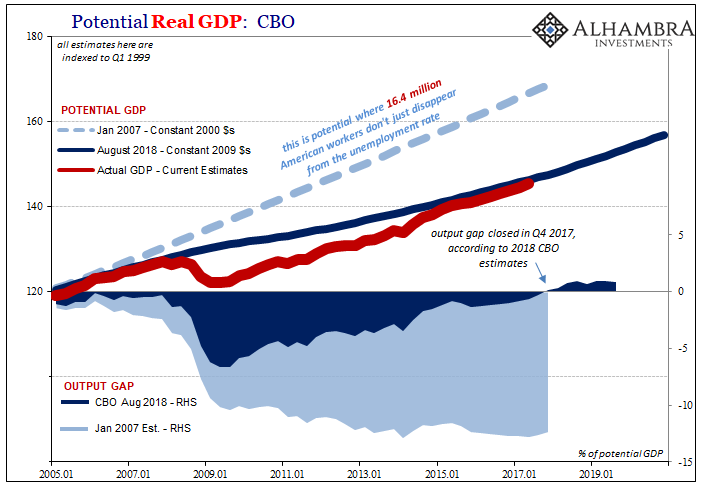

In addition to the unemployment rate, as noted at the outset, Economists and central bankers (redundant) also had output gap calculations which showed the economy had finally reached its (much reduced) potential therefore finally eliminating the output gap. Not only inflationary, it was reaching the point of (redefined) success.

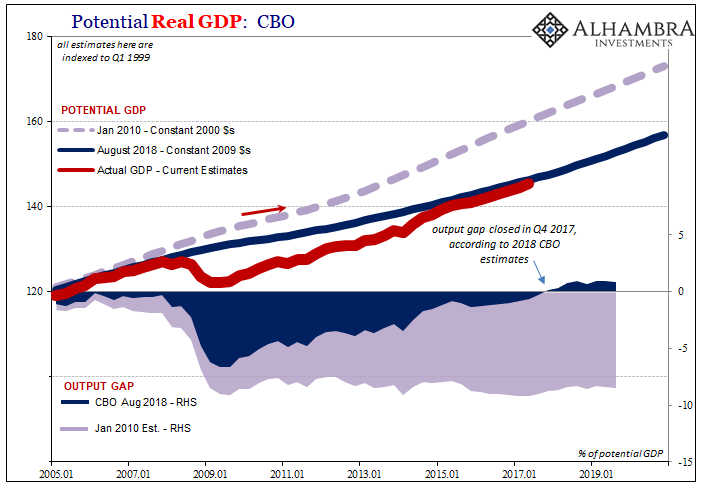

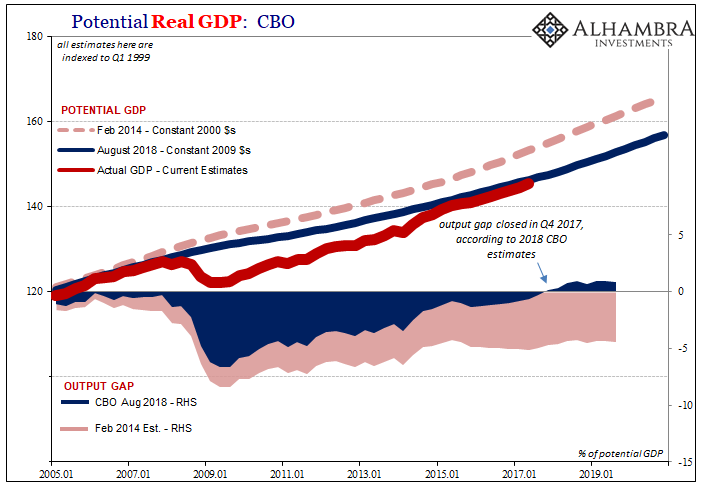

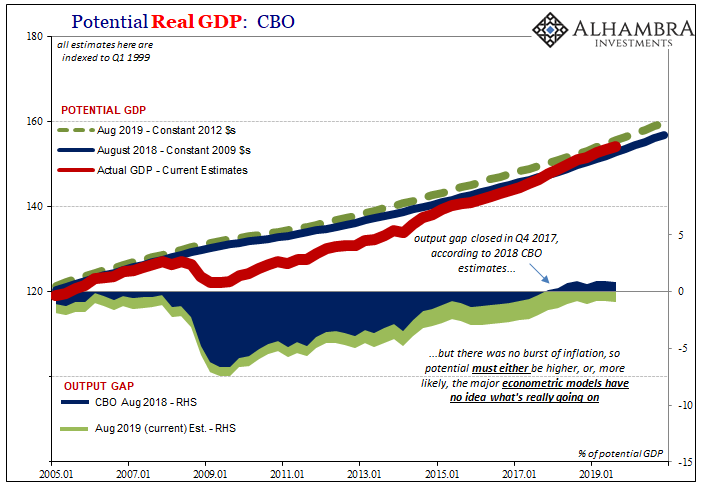

But these were not solid calculations, more wishful thinking than anything. You can see above just how much econometric models had to move potential downward in order for the output gap to be closed. Using prior estimates of potential, even those from as late as 2014 and 2015, the output gap in late 2017 and early 2018 remained enormous. The implications of those numbers were dramatic therefore they were “revised”, completely rewritten so as to force economy and potential to meet.

If Jay Powell taking over for Janet Yellen was right in his intial hawkish stance, then the updated CBO numbers (from 2017 forward) would be, too. Unemployment rate plus closing the output gap could only mean serious outbreak of inflationary pressures.

That’s especially true since the economy accelerated a small amount in early 2018, which by 2017’s view of potential put it substantially above. Epically scarce labor market as well as operating past NAIRU. Guaranteed inflation acceleration, right?

No. Never happened. While Powell and the central bank folks have tried to rely even more on R* in 2019 to attempt to explain the huge miss, the CBO’s models recognized how that wasn’t really an option. If there was no inflation, and there wasn’t, the output gap could not have been closed.

And that brings us to August 2019’s CBO figures:

Yep, the models have revised potential upward. That’s the only way to explain 2018’s failure to follow up from 2017’s inflation hysteria. When they all told you there was no slack, and the recovery had happened, there actually was slack meaning it hadn’t.

Again, this is not some trivial distinction; it goes right to the heart of everything increasingly going wrong over the last decade. Officials have no real sense of what’s going on in the economy, and their continuing output gap misses prove it.

Is there slack? Is it all gone? They don’t know.

And if you don’t know that, then you don’t know anything worth knowing.

Because if there is slack in the economy, macro slack, then R* is just a bunch of cooked up gobbledygook intended really for CYA. If there is still macro slack more than ten years after the big event, then QE and all the rest actually failed.

The CBO, obviously, has minimized their estimate of slack in the latest runs. That doesn’t matter because we would expect them to minimize it. What does matter is that the organization and its orthodox models in good mainstream standing have admitted that in every likelihood it is the ongoing slack which best explains how things have unfolded recently.

And since they can’t really get a handle on it, they aren’t a very good judge of these things, it isn’t for these models to tell us how much slack there might be. All we care about from the CBO is that they now acknowledge how there must be some. They’ve conceded the big one.

From there, we can make our own good sense, common sense judgments about how in the world that can be and what might be wrong to leave the US (and global) economy in such a bad situation. If there is some slack, it may not be so difficult to imagine, given the true state of the workforce, how there really could be a lot of it. September’s repo rumble just reminds us of its nature.

Economists and policymakers (redundant) absolutely needed inflation to show up in 2018. They were not forecasting it based on a solid understanding of where things actually stood, they were hoping to be let off the hook. They were hoping to push past slack because slack is the prosecution’s key piece of evidence which will convict them.

It is the smoking gun.

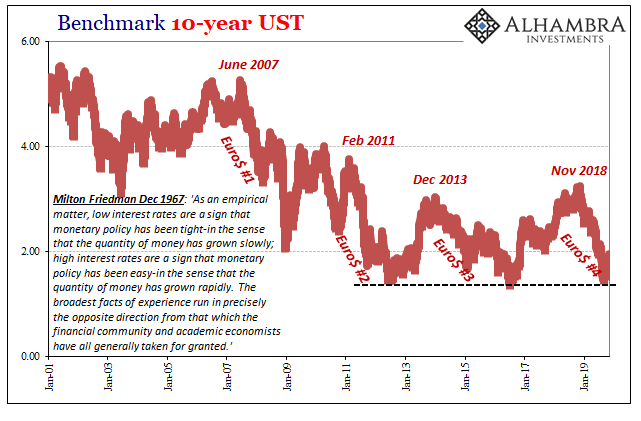

They really don’t know what they are doing. Keep that in mind as Euro$ #4 inches closer to its possible Phase 2 and everyone you are supposed to follow without thinking keeps telling you nothing’s wrong. Recession is the least of our worries, even though it is a substantial one.

Stay In Touch