Back in April, while she was quietly jockeying to make sure her name was placed at the top of the list to succeed Mario Draghi at the ECB, Christine Lagarde detoured into the topic of central bank independence. At a joint press conference held with the Governor of the Reserve Bank of South Africa, Lesetja Kganyago, as the Managing Director of the IMF Lagarde was asked specifically about President Trump’s habit of tweeting disdain in the direction of the Federal Reserve’s Chairman, Jay Powell.

Lagarde first responded by reciting what she sees as the modern central banker’s three central principles. According to her, these are: accountability, transparency, and communication. All are believed required “in order to be credible and in order to deliver on our mandate.”

Yes, but how?

[T]here are different ways around the world to organize one’s selves, clearly, when you are a Central Bank Governor. But independence has served them well over the course of time and hopefully will continue to do so.

They are going to communicate clearly and transparently in order to be accountable, but don’t anyone dare tweet about it? Central bank “independence” has become more than a buzzword of late.

While everyone likes to think of it in political terms, meddling politicians who always want to “print money” against the steady, sound advice of their studious monetary stewards, independence has meant for too long the utter lack of accountability. Global growth doesn’t just disappear for decades at a time.

This is especially true in the age of QE and zero interest rate policy – there is only QE and zero interest rate policy because independence means no one can change the setting from the outside. On the inside, apparently there’s only the one kind of central banker. Very transparent in that respect, too.

The urgent focus on the topic earlier this year was due to converging cross currents. A world economy going wrong with no one able to define any real answers, and the growing impatience about that very fact. Accountability? The collective global populace has been incredibly patient, almost unbelievably so, in giving these people chance after chance to get it right. To get anything right.

What happened to the recovery? Silence.

This latest round began, though, in India. That country’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi went well past Twitter and openly battled with then-Reserve Bank of India Governor Urjit Patel. It was ostensibly over the same thing irking President Trump. Rate hikes.

That wasn’t, however, Governor Patel’s real problem (nor Jay Powell’s, as we are finding out) and it wasn’t really what set Modi in motion. In each and every case it all traces back to Christine Lagarde. Not her specifically, but how she is another cookie cutter monetary official.

Lagarde had issued her same stifling, homogeneous decree late in 2017.

The long awaited global recovery is taking root…Policymakers should use all tools at their disposal to act now, and take advantage of the period of global growth. As I said, let us not let a good recovery go to waste.

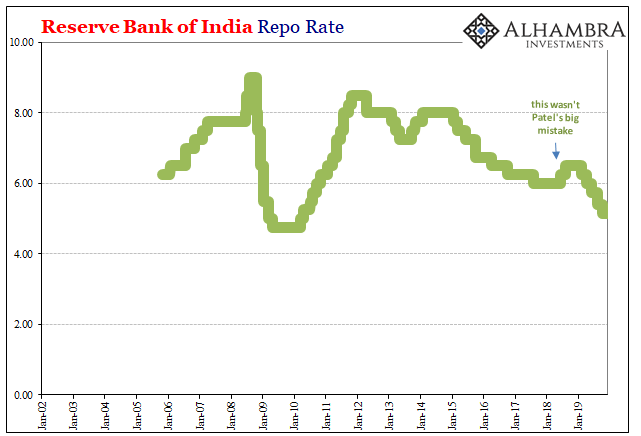

That’s all Urjit Patel (and Jay Powell) was doing. Following along from the mainstream central banker-driven consensus, he began to hike rates like he was supposed to.

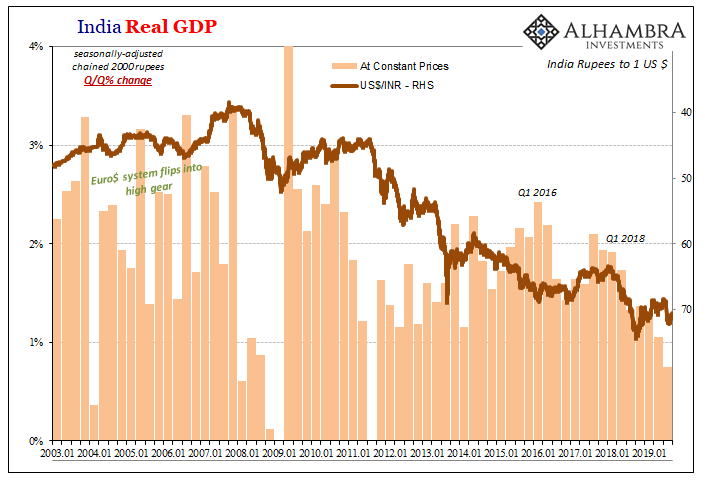

Unlike central bankers who have no skin in the game, politicians in India had already noticed “something” had changed, not for the better, and that this inflection happened several months before the first benchmark increase. While Patel was complaining about it in the pages of the Financial Times, pleading himself with Jay Powell to wake up about global dollars, Modi grew increasingly frustrated and worried.

Not only had weird things begun to happen in India’s “shadow” monetary system, the currency was “somehow” in freefall. It didn’t take the economy long to feel the impacts; not from Patel’s later modest duo of rate hikes, rather these indecipherable, shadowy external pressures.

And not trade wars, either. A few billion in US tariffs on Chinese goods don’t do this to India’s economy:

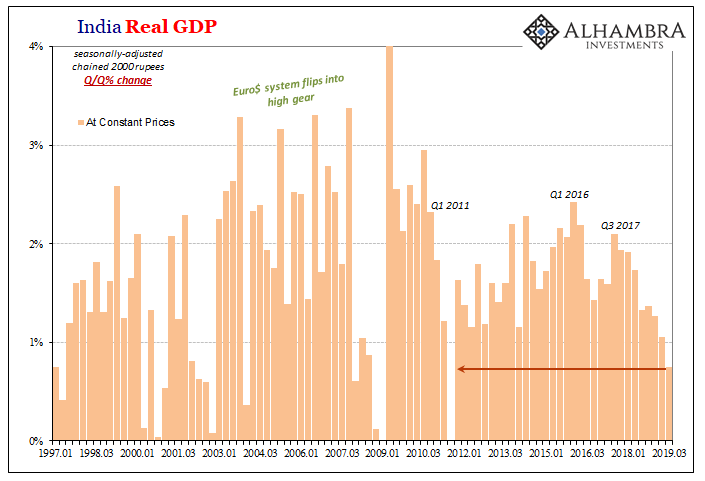

The numbers are increasingly harsh. According to figures released last week, Real GDP in India increased by just 4.5% year-over-year during the third quarter of 2019. That sounds like a lot, but it isn’t. That was the country’s worst quarter in more than seven years.

On a quarterly basis, the rate was all of 0.7% (pictured above). GDP expansion hadn’t been less than 1% in any quarter since the third one of 2011 – the kickoff of Euro$ #2. Unlike then, the Indian economy during this one has been slowly squeezed for years already.

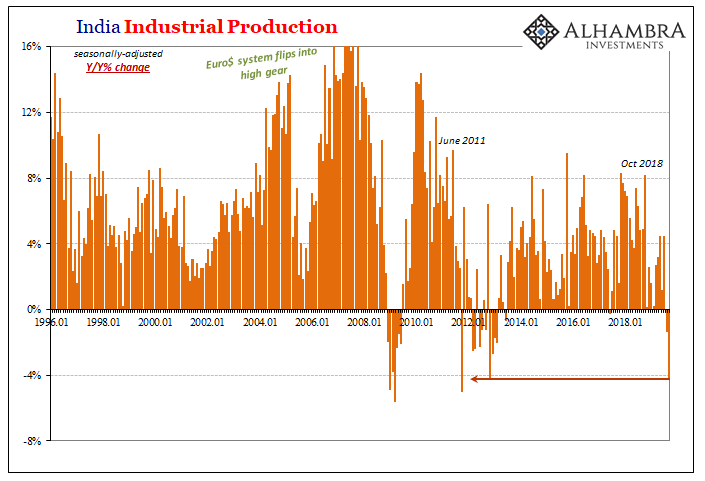

And there was even more bad news in late November. As a developing economy, India depends upon its industrial sector for marginal potential as much if not more so than others in the same EM category. Modern India is Indian industry.

But the government reported that in the month of September 2019, Industrial Production crashed. It was down 4.3% from September 2018, the second consecutive negative number. Indian IP doesn’t have many negatives let alone those at or near -4%. The latest figure for September was the fourth lowest in the entire series.

Patel was replaced by close Modi ally Shaktikanta Das last December. Das has been playing ball his entire tenure, as has Jay Powell this year. The Reserve Bank of India like the Federal Reserve has been cutting rates. The RBI, though, much more aggressively – five cuts so far in 2019 (four of them 25 bps, one for 35 bps), with all expectations for a sixth when the central bank’s policy committee meets again on Thursday.

It obviously isn’t working.

The reason is because Patel’s grave mistake, and India’s potential downfall, wasn’t his rate hikes. It was instead how he would only mimic the unaccountable mainstream central bank chorus on every major point. Patel, as Powell, really believed what Lagarde had said late in 2017 while the tide was already turning against us all. The global recovery was “taking root” only in the official mind.

That is why he “resigned” after Modi meddled. More and more revealed as yet another false dawn, the world’s third, patience is wearing dangerously thin and not just outside of the still-cloaked central bank boardrooms.

Powell made and continues to make the same error. And central bank independence means no one will challenge his views; nobody can stop him and force him to confront these big mistakes. So, they continue unabated.

Even if you could replace Powell, who would follow? India is the perfect example. Das may be a slight improvement upon Patel because he realizes the situation for what it is, but Das still has no idea why this is the case. He’s merely cutting rates in India because that’s what it says you are supposed to do in the standard, orthodox central bank handbook Patel was using.

The same one Jay Powell is still using. He, too, sees economic weakness all of a sudden and also doesn’t really know what to make of it. And now that Christine Lagarde has been installed in Frankfurt at the ECB, she looks and sounds exactly the same as them.

There’s only the one kind of central banker.

While that’s all long-term stuff, the world’s more immediate and pressing problem is – did you see what’s going on in India? For a global economy supposedly on the mend after a recession scare, this doesn’t exactly fit into that narrative. At all.

Everyone knows China’s in a big struggle. There’s not much positive elsewhere, whether recession in Europe or lingering unease about the US economy, too. Now Japan.

India was supposed to be the last bastion of the old way, the precrisis potential whatever was still alive from it. If that place isn’t immune from the “dollar double whammy” then that’s it, no one is. It’s a massive blow not just to those trying to look past “recession fears” but more so in terms of risk and the self-reinforcing eurodollar processes (even more risk) that make all these things go.

Right, and now wrong. Truly globally synchronized downturn. It sure doesn’t seem past tense in this crucial location. And because central banks have largely secured their independence, Urjit Patel’s ouster still the outlier, there can be no account of the problem and therefore no accountability for it.

That is what will increasingly endanger central bank “independence.” The once-more rising stench of failure emanating from the grievously remorseless spread throughout all corners of the world.

Stay In Touch