A tale of two economies? At first, it might seem that way. However, this isn’t the first time apparent divergences have arisen. On the contrary, “decoupling” is a recurrent theme even though, in the end, it never happens.

Of the major data released today, one set from the United States, the other in China. The former seemingly justifying the Federal Reserve’s rate hike panic, therefore deserved of more scrutiny and like attention. The latter just the latest COVID we’re told not to get worked up about.

Reality would have you play it the other way around, however, given that any apparent differences aren’t categorical rather a matter of timing. In fact, both almost certainly suffering the same problem just exhibiting different stages of it.

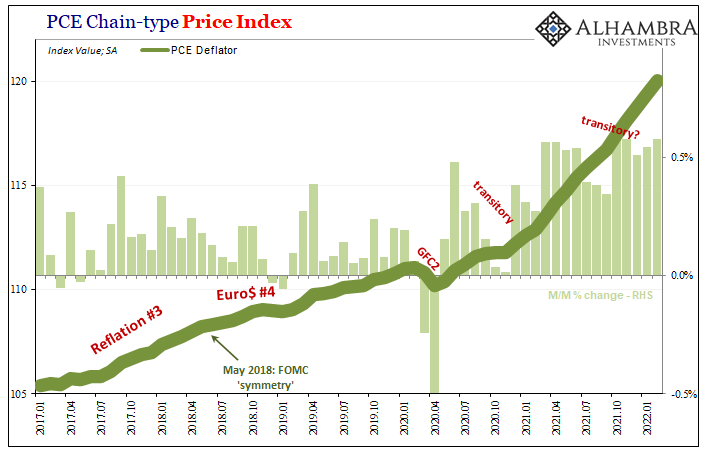

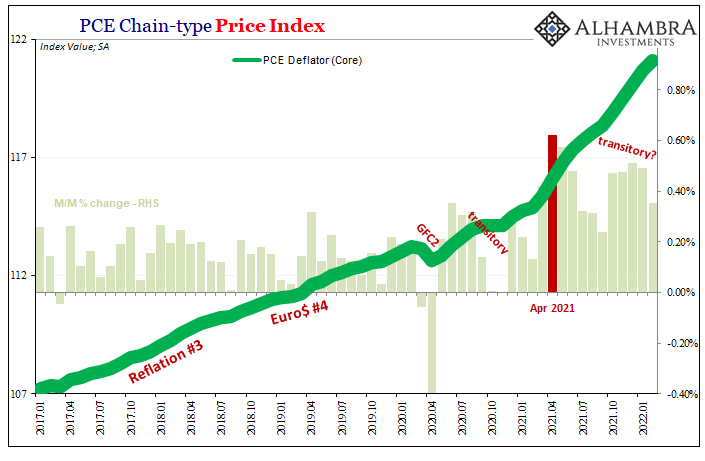

America’s Bureau of Economic Analysis, having put out some critical GDP numbers for Q4 yesterday, today it spit out PCE data, including those regarding consumer prices, for the month of February 2022. Red hot, highest in…you know the rest.

The headline deflator managed to accelerate upward to 6.35% year-over-year, another one with better than a half-percent monthly increase thanks to pre-Putin oil prices.

A tiny bit less moving, though not by much, the core PCE Deflator. Though a new annual rate high of 5.40% year-over-year, the monthly change was the least since last September.

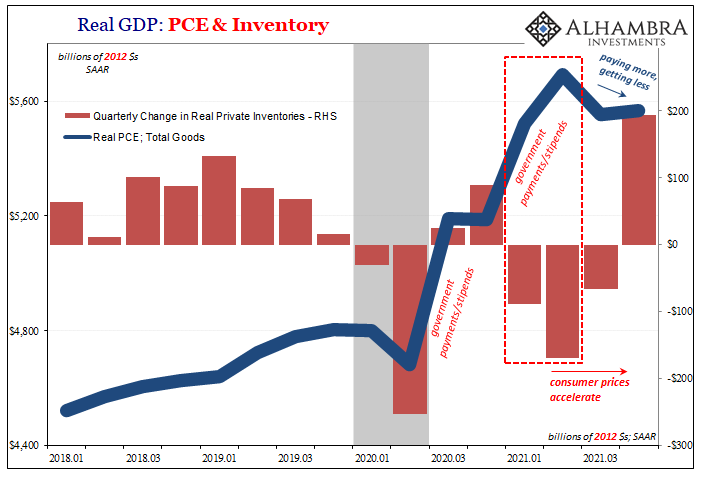

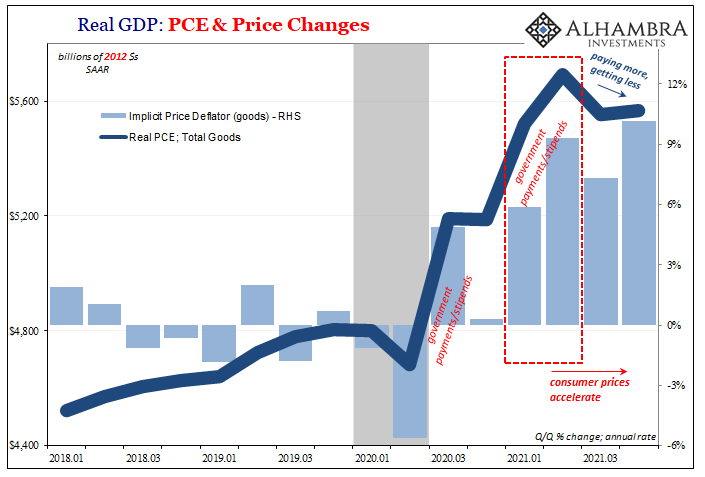

Even if that is a meaningful decline in pace, these US consumer price numbers are already old news. These are backward looking at the leftovers from last year’s supply shock, the same very clearly demonstrated in those GDP numbers; in particular, the ups and downs for US-held inventory.

And if their latest upward trend for Q4 2021, with Census Bureau estimates chiming in affirmatively on them already across most of Q1 2022, then the downside of the supply shock may already be emergent – in the form of demand destruction.

In other words, an inventory cycle’s inevitable downside. Retailers and wholesalers accumulate unsold goods, only this time it isn’t just your any old accumulation, it’s biblical. At the same time, demand for goods wanes. In 2022’s case, lackluster labor market combined with further calendar distance from the reason for the demand in the first place, Uncle Sam, both together to go along with consumers having to pay more to get less, all of it only adding to the rising backlash in the only bright global economic spot – US goods.

But these goods are not made in the US, and least not that many. American manufacturing isn’t nothing, yet much of what gets produced comes from elsewhere. And that means an unhealthy dose of China.

While the US BEA told of still-high consumer prices, China’s NBS showed something else entirely. But what? According to that government, COVID shutdowns and dastardly Russians.

I’m not joking; the NBS spokesman, Zhao Qinghe, a senior statistician of the Service Industry Survey Center, blamed unspecified “international geopolitical instability factors” for what were across-the-board indications of outright contraction.

Recently, clustered epidemics have occurred in many places in China, coupled with a significant increase in international geopolitical instability factors, the production and operation activities of Chinese enterprises have been affected to a certain extent.

OK, those things “to a certain extent.” What other “extents” might there be?

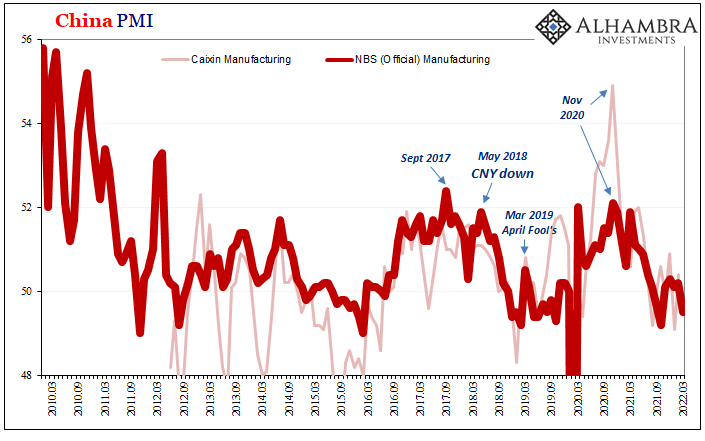

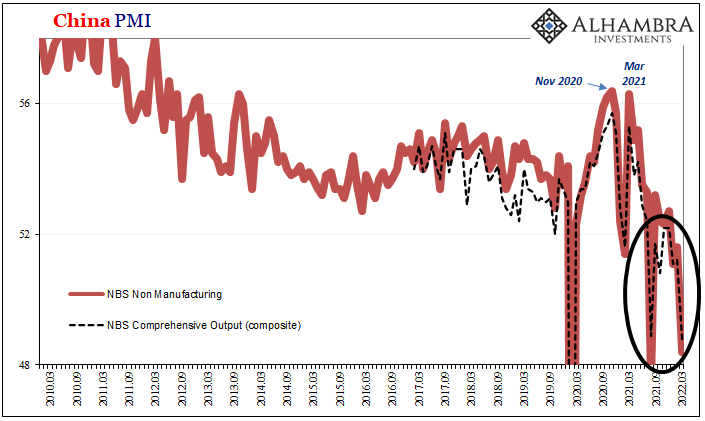

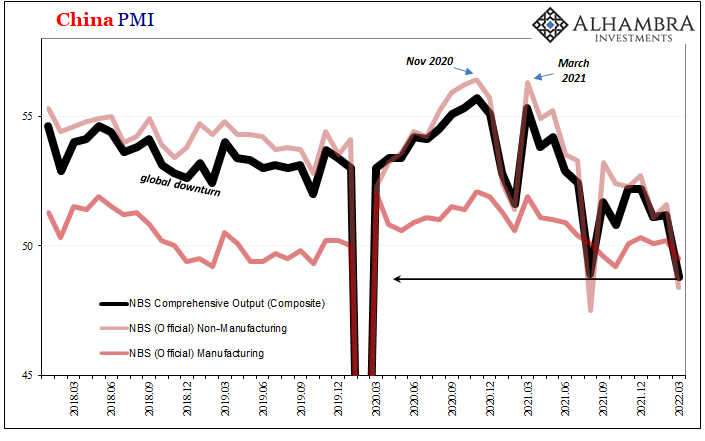

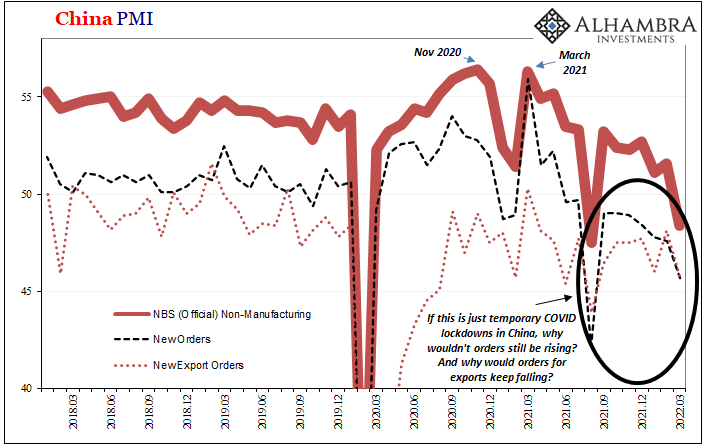

By the numbers, the official (NBS) manufacturing PMI fell to 49.5 for March 2022 from 50.2 for February. The non-manufacturing index came out at just 48.4 this month, way less than 51.6 last month and among the lowest in its history. The “general” or composite, combining the output numbers for both manufacturing and non-manufacturing, likewise extreme low down to 48.8 (worst since February 2020, now the second lowest in its history).

Sure, there have been reported corona outbreaks in Shenzhen and Shanghai, and for what we can gather China remains committed to its insane zero-COVID policy (I still think for other reasons, including to cover up just what I’m writing about), and while that might explain the volatility in the data month-to-month, and the depths to certain months during this volatility, it does not, nor can it, explain the constant overall trend which remains regardless of disease or geopolitical aggressions.

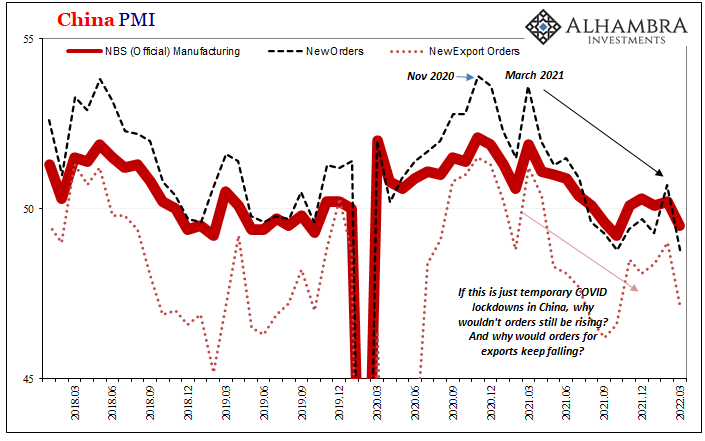

More than that, however, orders falling everywhere. For the manufacturing PMI, new orders 48.8 from 50.7, and new export orders 47.2 from 49.0; non-manufacturing just atrocious, new orders 45.7 from 47.6, and orders for export 45.8 from 48.1.

Why would lockdowns lead to falling orders? More to the point, why would intermittent lockdowns in China lead to continuously falling orders coming from outside of China for what China should be producing? You might suspect other “extents” at work here.

If a city or region were put in quarantine, no one would cancel an order for goods (or services). They’d either reroute their orders to someone else in China (neutral for something like these PMIs) or just keep their orders and wait a couple weeks (at most) for the government to lift its restrictions.

Yet, for the second half of last year, both orders and orders for export have been nonstop weak if not contracting, at least by the standards of how these kinds of sentiment indicators measure such things (meaning, below 50). Solidly underwater for months on end would indicate more pressing, persistent problems.

Such major downside in the months that just so happen to lead up to, and then coincide with, the incredible inventory flood finally reaching American shores. These are unrelated?

I highly doubt it, and so do the increasingly inverted curves. Furthermore, these only fuel doubts about the better-than-awful-last-year January-February “hard data” and whether these others show even modest momentum moving forward.

And if this more than reasonable doubt does indeed prove to be the case, then forward-looking Chinese “soft data” renders all those screaming US consumer price headlines moot, not to mention Jay Powell’s rate hike theater. Those latter looking backward at the past supply shock and seeing the consumer price reverberation from what already happened, whereas China’s PMI estimates show a big swath of the global economy just may have gone forward over the edge into that same shock’s downside.

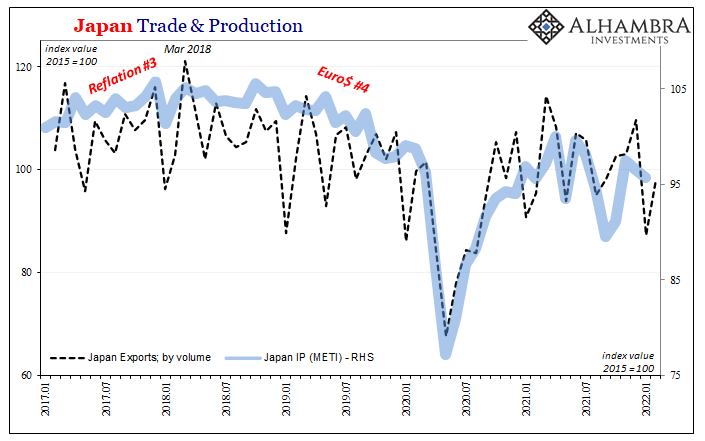

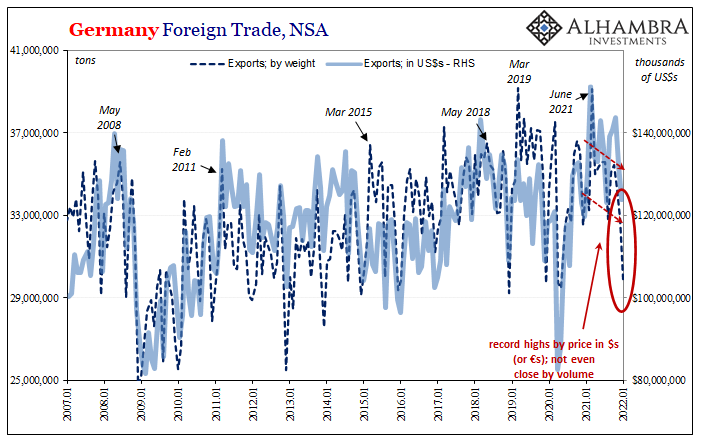

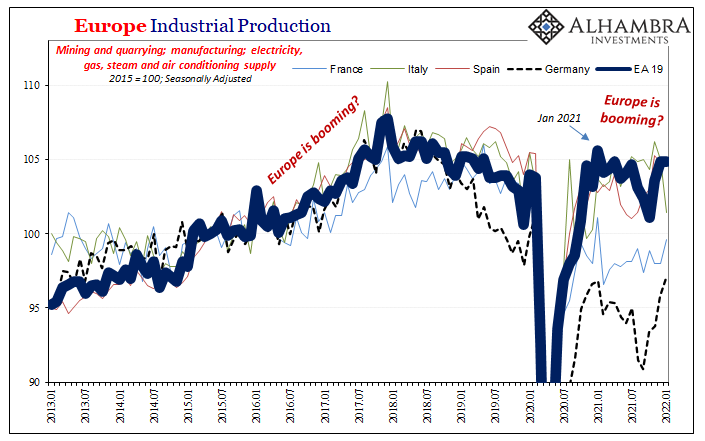

Not just China, either.

There never is decoupling. Eventually, the downside comes to everyone. Even forty-year highs for what isn’t inflation. So much worried fascination over the wrong thing, the PCE Deflator, when the vastly more relevant worry is displayed in Chinese. It’s just not Russian nor pandemic.

Stay In Touch