Engaged in one of those protectionist trade spats people have been talking about, the flow of goods between South Korea and Japan has been choked off. The specific national reasons for the dispute are immaterial. As trade falls off everywhere, countries are increasingly looking to protect their own. Nothing new, this is a feature of when prolonged stagnation turns to outright contraction.

While the dispute with Japan hasn’t helped, it isn’t responsible for the level of decline the Republic of Korea is reporting. Preliminary estimates for the month of September 2019 suggest the volume of goods leaving the country collapsed by more than 21% from September 2018.

The last time the Korean economy faced this degree of external negative pressure was 2009. Like Japan or Germany, Korea depends to a high degree on global trade.

There was already a building sense that trade wars – specifically the dispute and tariffs put on between the US and China – just doesn’t add up to what we are seeing across the world. You don’t get a serious possibility of worldwide recession from a few billion in levies on specific goods back and forth between just those two.

Economists and central bankers have instead attempted to attribute this growing economic downside to “sentiment.” Supposedly, businesses throughout the rest of the world are worried about where protectionist behavior might strike next. According to the idea, they are paralyzed and that’s what’s holding everything back.

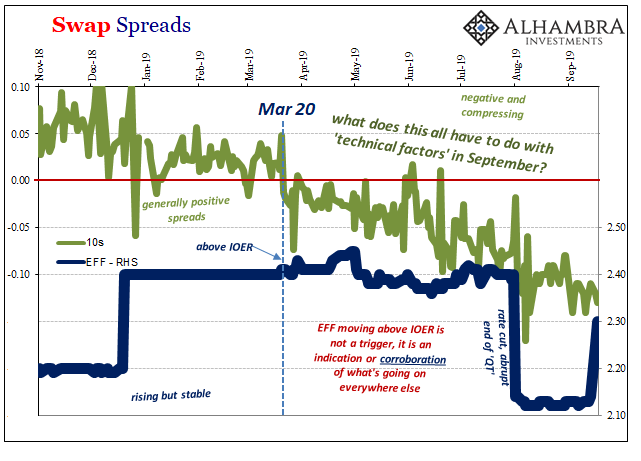

But then along comes the repo rumble and fed funds to take everyone’s mind in a different potential direction. The dots are not yet connected, of course, but as I wrote there was already some honest analysis that “trade wars” just don’t seem to fit the conditions even before the funding mess of last week.

Evidence is accumulating that the effects of trade tensions are greater than previously thought, the OECD said, urging all countries to stop erecting tit-for-tat trade barriers and to fight the economic slowdown with a fiscal stimulus, where public finances allowed.

Some kind of tension is greater than previously thought. In the absence of any other explanation, sure, tit-for-tat trade barriers even though they just don’t add up. The more financial and monetary pressures surface, the more the connection can be at least considered (outside of central banks and central banking, obviously).

There’s far more going on in the world. Far more downside.

Investors are increasingly fearful of a global recession, according to a survey of many of the world’s biggest asset managers…

“People have definitely bought into the bearish macro view,” said David Bowers, ASR’s head of research. “When you look at the pattern over the past four or five years, it is definitely quite an important inflection point.”

What’s supposedly still driving what’s left of any optimism is…stimulus. According to the mainstream view, it has to be trade wars but somehow more than trade wars and these are pushing the global economy toward a recession no central banker will say is a realistic possibility. Fret not, however, because once they realize there is serious and unanticipated downside risks they’ll absolutely, definitely get their act together in a heartbeat and save the day.

Like they did ten years ago?

People are thinking the cavalry is going to come quickly to create stimulus to provide that turnaround.

That’s the other thing about the mid-September repo rumble. Not only does it suggest something else might be going on out there in the global financial system which unlike trade “sentiment” actually could explain the degree of global weakness, at the same time these recessionary questions are being raised, it also brings up substantial problems for central banks like the Federal Reserve.

It’s one thing for people to wonder just how powerful monetary policy is after all this time and little to show for it (particularly in Europe). It’s quite another for a clear and public demonstration at the very moment the FOMC is announcing a rate cut supposedly to add monetary “accommodation.”

Jay Powell may think he has fooled the general public into believing that repo and fed funds were successfully handled, but the mere fact that repo was on the front pages for several days before and after the FOMC announcement suggests otherwise. While most people pay little or no attention to money markets, for them to suddenly be forced to do so was a little unsettling.

In other words, the US central bank is already way behind the curve on two key fronts. Its current forecast is nothing like a global recession, mere cross currents easily handled with only (only!!) two rate cuts. If things are already worsening, more “global turmoil” as Korea suggests, how long does it take before the models change to incorporate that very different set of circumstances?

Experience suggests “stimulus” only shows up way, way after it is ever needed. Optimism (really recency and confirmation biases) predominates until negative pressures are too obvious to ignore any longer. A state of denial always, always persists on official levels.

The more important consideration is, once they catch up with economic conditions as they are what are they really going to do about them? Not in theory but practice. Stimulus, of course, but if that only means more rate cuts or perhaps another QE (or standing repo facility) then what happened in September, the dress rehearsal, should be a(nother) reminder of how little those things can accomplish.

Bank reserves just don’t matter.

We already know there’s one class of investors who aren’t waiting around for Jay Powell to figure everything out and get his act together. The very “investors” who have been piling into safe haven assets of all kinds (especially as they related to repo) for nearly a year (dating back to the first week of October 2018). It’s the very system which we are all supposed to count on to deliver all that “stimulus.”

Yeah, that’s what the repo rumble did. As its New York branch clumsily admitted (for once), the Fed needs the banks for any kind of “accommodation.” For nothing more than a seasonal bottleneck, they said, no thanks. What happens if all these risks become more than risks?

In other words, if you are blaming trade wars and waiting for monetary policy to fix the economic damage from them, you, too, are way behind the curves. In one sense, that’s what happened last week. A dress rehearsal for some, a reminder for everyone else.

Stay In Touch