The second most frustrating aspect of trying to analyze global shadow money is how the term “shadow” really applies in this case. It’s not really because banks are being sneaky, desperately maintaining their cover for any number of illicit activities they are regularly accused of undertaking. The money stays in the shadows for the simple reason central bankers don’t know their jobs; even after a somehow Global Financial Crisis in 2008, they don’t realize the full scope of what goes on offshore or why it might be so important.

And that’s actually the most maddening part. If they would see past their own rigid ideologies, and be open to a world that doesn’t work the way they tell everyone it does, we wouldn’t have to go digging through statistics and data that was never designed to track and measure some of what goes into, and comes out of, those offshore shadows.

I’m speaking specifically about TIC and how it might help us put some further estimates on repo. The reason we might want to do this has finally become self-evident. At least until everyone forgets about mid-September.

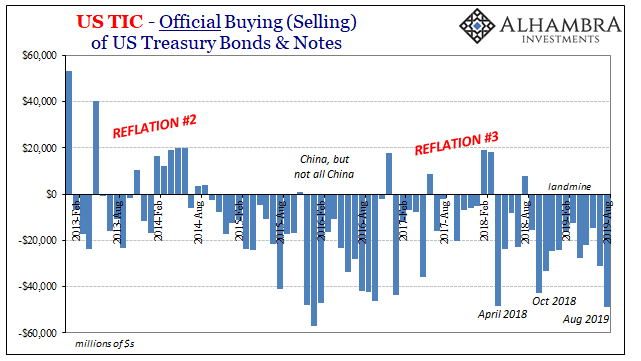

The place to start is inside TIC but outside of repo. The month of August 2019, which is the latest data made available last week by the Treasury Department, wasn’t a pretty one. The Fed had just “cut rates” for the first time in a decade and though Jay Powell had said it would be one and done the market immediately took off – the wrong way.

UST prices spiked and yields worldwide plummeted. The Fed had, in fact, confirmed to the bond market anyway that officials, too, had become concerned enough they would act on them. And they are among the last to figure these things out (Economists talking about stock market are the very last).

The repo rumble showed up in the middle of the following month.

According to TIC, during August as UST prices skyrocketed with the demand for collateral, among other flight to liquidity factors, foreigners were selling tons of their UST holdings. It’s pretty much the opposite of what the BOND ROUT!!!! folks say should happen. In reality, when foreigners “sell” their US$ assets it’s a dependable sign the global dollar shortage has become acute (which drives the “strong worldwide demand for safe assets”).

In fact, for foreign official holders of UST’s August 2019 was among the worst months. That actually makes sense in the context of the bond market and the Fed’s ridiculous attempt at claiming a “mid-cycle adjustment.” No one was buying it, and that pushed foreigners into “selling.”

The reason I use the scare quotes around the word “selling” is repo. It’s not really clear that’s what particularly foreign official institutions (FOI’s) do with their holdings. It seems like it should be very straightforward; you own something or you don’t. That’s not how the global monetary system really works, though, and there is quite a bit of gray area in between.

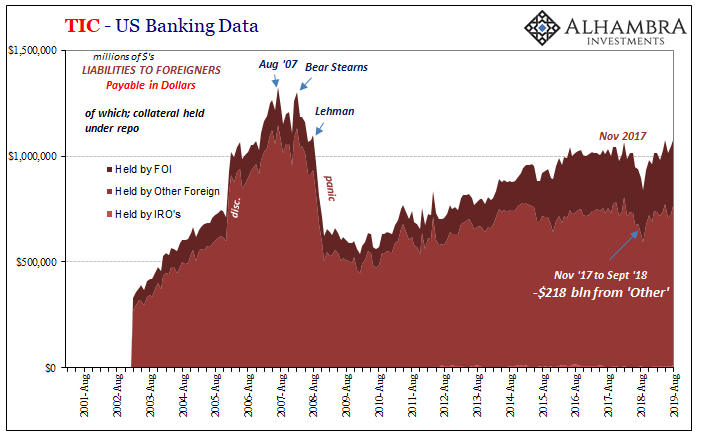

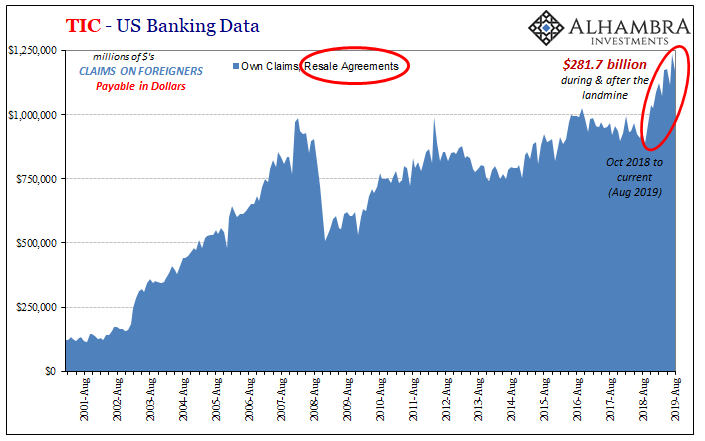

If we go to the banking data included with TIC, and specifically the repo section (because, despite TIC’s ill-conceived limitations, there is one), we find a couple of intriguing trends.

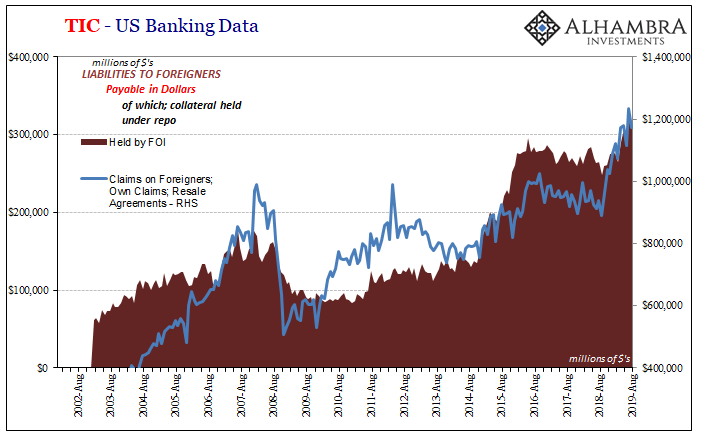

Between November 2017 (China’s tragic admission that there was no globally synchronized growth) and September 2018, the month before the landmine, TIC displays an unusual and unusually large decline in the level of US$ liabilities tied to repo US banks owe to foreign institutions of all kinds – but mostly “other foreign.” We don’t have any more specific data than that but if you’ve been following me since around that time you know that I believe there was a collateral disruption which began to register during that period (especially May 29).

During this same time frame when the dollar stopped falling (exchange value) and then started rising again, perceptions of a riskier world in the wake of China’s big announcement undoubtedly sparked a collateral re-assessment – junk and EM junk transformations that almost certainly took place during the latter half of 2016 and throughout 2017 under “globally synchronized growth” were re-examined in light of what would be far riskier dimensions if (when) globally synchronized growth came to be recognized as yet another false dawn (which it increasingly is).

Thus, if we take the TIC data you see above literally, it seems as if an enormous collateral black hole opened up. Starting in October 2018, two things happened – the collateral pressure at least as far as what showed up in TIC began to close up at the very same moment UST yields began to top out and then plummet.

In other words, the collateral hole opened up to September, and then beginning in October there was unleashed a scramble for the best collateral (including more than UST’s) to maybe fill it back in.

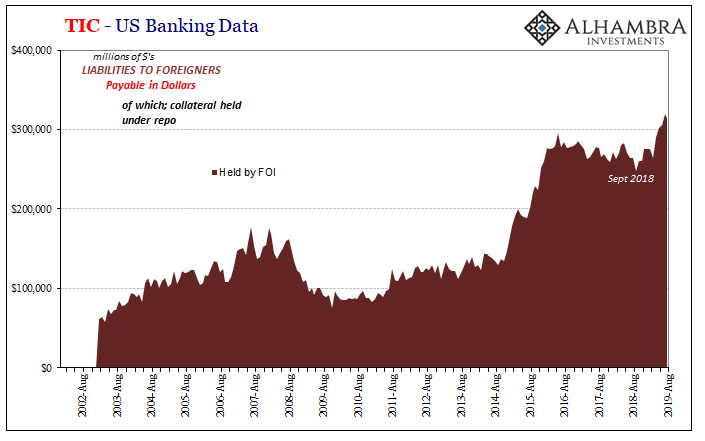

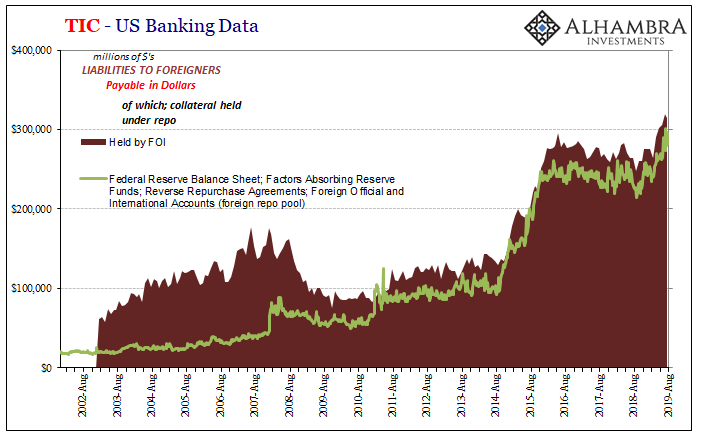

And that’s not all; TIC also tells us that the FOI’s were partly involved in that process – somehow. Beginning also in October 2018, US bank liabilities to foreigners of which was collateral held under repurchase agreements to those FOI’s, that specific balance jumped substantially. Collateral and repo went through the roof to record highs.

It wasn’t just TIC that told us something was up with FOI’s, UST’s, and repo. You might already recognize the pattern, particularly in the years after 2011:

Yes, the foreign repo pool shows up to corroborate TIC, too. But it’s not the only place where we see the same outlines (of Euro$ #4 in repo) being repeated. We can also find it on the other side, what I call the blue side of TIC which represents dollar flows going the other way.

If, generally speaking, the red is US banks “borrowing” from offshore entities the blue is US banks lending into those same shadows. As I’ve noted several times previously, when in times of funding distress the level of repo (on the blue side that means US bank resales) usually jumps. The repo market, as noted here in TIC as well as in Z1, is the real lender-of-last resort to the global system (because the Fed’s repo operations aren’t really repo operations).

Again, same time frame but on an even larger scale.

What I’m proposing here is something I talked about the first time the repo pool showed up on anyone’s radar: Euro$ #3. I wrote back in May 2016:

The mainstream usually refers to the RRP, either this or the other one, as a place to “park cash” but in reality it is a last resort of collateral supply. In the first place, why would foreign central banks suddenly decide to swap holding UST’s for RRP balances? Did they suddenly fear liquidity in the UST market that was, at that time, actually surging? It’s as absurd as suggesting Wall Street was suddenly “stuck” with UST’s that they couldn’t offload.

Without understanding the dynamics of the collateral part of repo these things tend to make little sense. Dealers are stuck (again) with UST’s they can’t sell? No way; they want those UST’s. FOI’s sell their holdings of the same and then park the proceeds in the foreign repo pool (the RRP being referred to above) to get a better repo rate (as some at Credit Suisse always suggest)? No way; they’re making what seems like their own collateral swap.

OK, that’s a whole lot to digest, so let’s go back and review. Late 2017 to September 2018: globally synchronized growth revealed as a fraud, risk perceptions rise, collateral transformations using junk or EM junk (CLO’s and otherwise) get reprocessed. That opens up a huge collateral hole that as 2018 moves forward becomes a bigger and bigger problem (May 29, rising dollar, etc.).

In terms of FOI’s, they really start “selling” their UST holdings in October 2018 but parking a good deal of the proceeds in the foreign repo pool. The funds they don’t put in it are used to “supply” the marketplace starved for dollars. The funds that do end up there increase the FOI’s correspondent balances (their dollar buffer safeguard) while at the same time bringing back to them Fed collateral out of SOMA (the FOI is “lending” its cash to the Fed on Fed collateral).

So, the FOI has sold UST’s and, in the process, increased its cash buffer at FRBNY, by doing so ends up holding the same amount of…UST’s as collateral. These other UST’s, the Fed’s UST’s, unlike the FOI’s original holdings can be used in the global collateral stream – maybe if a local bank or financial entity is short of UST collateral because it had been using EM junk CLO Eurobonds previously?

And that might suggest how US$ repo balances (blue) can simultaneously surge when there otherwise seems to be a growing collateral shortage offshore (which there is). FOI’s perform what is a collateral transformation of their own; only from UST’s which used to be in the category of their own “foreign reserves” into now cash which shows up that way and collateral that doesn’t.

The official shadows?

The global system is left to these backdoor semi-official bypasses in place of disrupted collateral chains and flow. All of which suggests, especially given the balances involved here, those illuminated by TIC, anyway, an immense, highly disruptive collateral problem.

Therefore, an even larger potential collateral problem.

There’s really two ways of looking at this data, at least how I’ve described it here (you can certainly make up your own mind as to whether I’m interpreting these figures appropriately). On the one hand, the system has absorbed a pretty big punch to the gut, undertaking some questionable and misunderstood actions in order to get past it and having survived, mostly, the hit.

There was a pretty serious collateral shock and it didn’t blow up the world, no repeat of 2008.

On the other hand, I’m not sure it was all that much of a shock (credit spreads didn’t blow out) and furthermore (after April 2018) it became outwardly disruptive and continued to reverberate month after month after month until finally necessitating (landmine) what were pretty large consequent market flows and countermoves on the part of these FOI’s (and the Fed, too, if we take things up to the current time).

I tend to believe the latter is the bond market’s view of where things stand. The repo system didn’t really perform all that well (why in September suddenly everyone began talking about repo) under what might have been only the initial move to re-think the entirety of suspect global collateral chains.

Especially as globally synchronized growth has already become a globally synchronized downturn. And to which in response our benighted central bankers have begun to execute a plan which will…reduce the level of the best collateral available.

To wrap up as succinctly as I can: if we are still asking where are the dealers, and we are, there’s hundreds of billions of reasons already why they might have become so increasingly shy. And that’s just what we can see.

Stay In Touch