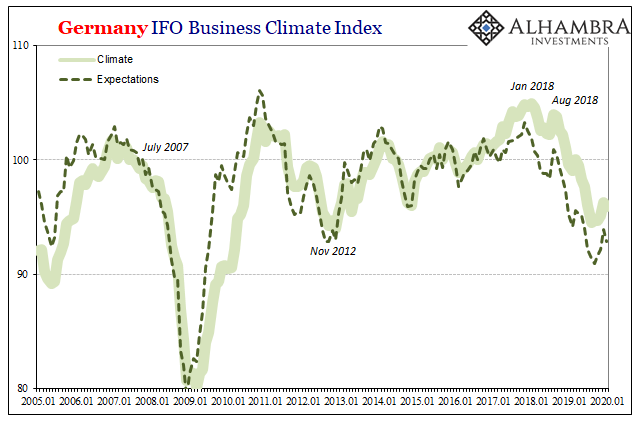

According to analysts and economists who watch these things, Germany’s IFO Business Climate Index was expected to continue its rise. Having purportedly bottomed out back in September, like other sentiment indicators this one had been on the rebound, too, if, though, much less than those others (especially the “stimulus” loving ZEW). While maybe not suggesting the turnaround we had been told to expect over the last few months of 2019, 2020 was going to open by still going in the right direction.

Instead, the IFO stumbles out of the gate. At 95.9 for January 2020, that’s less than the 96.1 put up in December and well behind the 97.3 which had been forecast.

And the only thing anyone wants to know right now is what this has to do with China’s coronavirus outbreak.

A legitimate answer is, not much if anything. Perhaps Germany’s business professionals being surveyed by the IFO are beginning to worry over the disease’s spread in China, and given how closely China’s economic fortunes seem to be linked with Germany’s they’ve grown concerned about the second order spillover effects. Economic contagion, not directly the actual pandemic.

The New York Times writes today that the coronavirus outbreak has “revived” global economic fears. In one sense that’s true, but not quite in that way. Those concerns about the worldwide downturn never really faded away; you were just told (over and over) that they had. The media’s appreciation for them is what may have been revived.

The United States and China had achieved a tenuous pause in a trade war that had damaged both sides. The specter of open hostilities between the United States and Iran had reverted to stalemate. Though Europe remained stagnant, Germany — the continent’s largest economy — had escaped the threat of recession.

Now, the world is worrying anew.

In that sense, the coronavirus is, in this context, the new trade war. The mainstream needs to blame something and given how convenient the timing between “protectionism” and the “unexpected” appearance of this globally synchronized downturn should the latter flame back up again, having never really been extinguished, China easily provides the next scapegoat (wouldn’t it be ironic if the virus was found to have jumped from goats to humans?)

The reason markets are reacting to the news of the disease’s spread is because the markets (bonds, anyway) know just how fragile the situation continues to be.

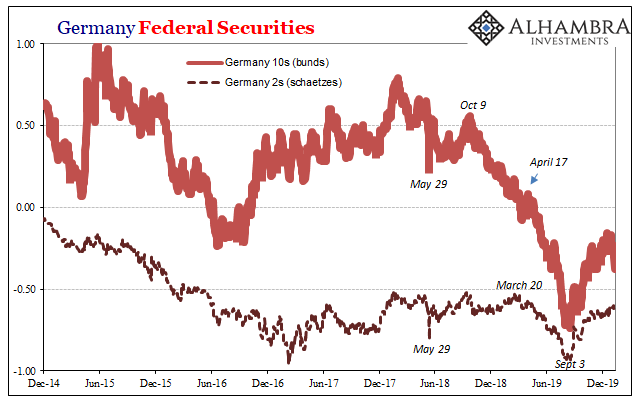

Begin with German bunds (and schaetzes). The idea that the global economy ended last year on the mend was based upon a fundamental misreading of global yields (and curves). It was said, repeatedly, that the whole bond market at once warned of impending doom into early September, an all-or-nothing brace-for-impact siren.

And then just up and canceled it as if it was just a drill. That’s what “they” have been saying.

That’s not what really happened. Bond yields dating back to late 2018 (the landmine) started to signal rising probabilities all throughout the world for bad things; liquidity as well as negative economic pressures and consequences. What Richard Clarida recently called the twin bill of global headwinds and disinflationary pressures.

The depths of the yield plunge notated very serious risks along those lines. The backup in yields since isn’t the market giving up on them, it is instead bonds pricing relatively less of a probability of only the worse case. And only a little less negative.

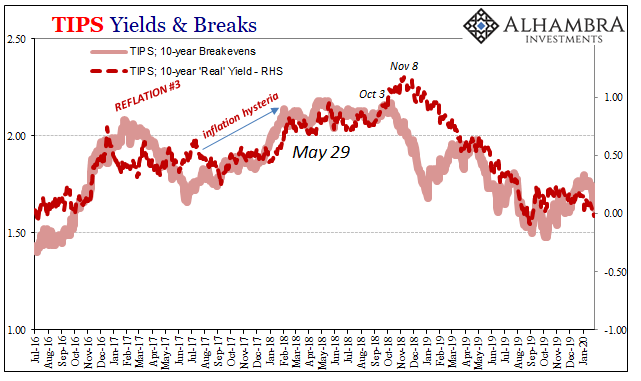

In truth, not much has changed since last August, even in the German bond market which had led the way forward (meaning downward). In every way, the last third of 2019 is comparable to the six or eight months of 2017-18’s inflation hysteria. The smallest little pause in trend has been made into the biggest yet ultimately hollow mountain. Back then, it was global growth that wasn’t really growth. This time, a rebound that isn’t (yet) the economy turning around.

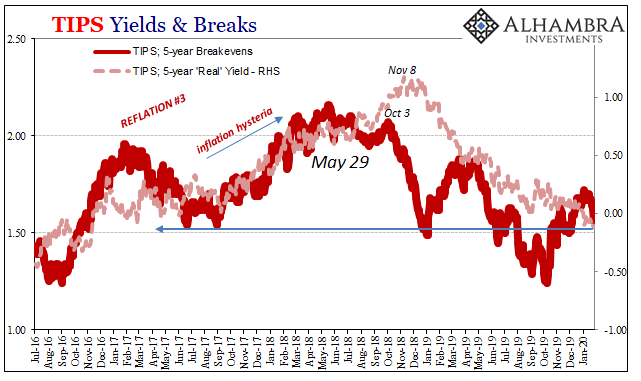

From German curves to those associated with the UST market, the difference has been minimal. Even inflation expectations among the latter haven’t been all that enthusiastic (and now are crashing again as oil does). Even while inflation breakevens in the Treasury market had gone partway back up, real growth expectations did not.

In fact, real 5-year TIPS yields keep sinking to new multi-year lows, not that far off from where the market was thinking at the depths of 2016.

The biggest misinterpretation, in my view, has been the idea of “inversion.” Since most people (including central bankers and everyone in the financial media) don’t pay any attention to the yield curve normally, it has become condensed into either the 3m10s or 2s10s; “the” yield curve is, in the public imagination, either of those two points but only those two.

And when one of them inverts that’s the trigger; not for recession, per se, but for the mainstream to begin taking notice the yield curve. Which is a shame because the yield curve apart from those two particular comparisons has been a bounty of information this whole time (meaning for more than the last two years).

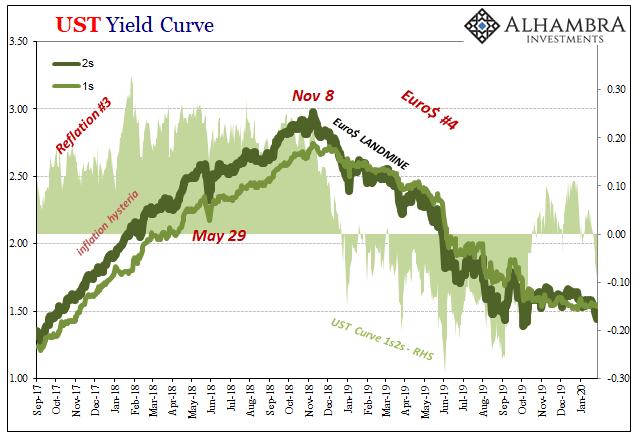

You can see above how the 1-year to 2-year space was one of the early parts of the curve to really flatten and then invert – long before the 3m10s or the 2s10s did. And like German bunds, the improvement in late 2019 wasn’t all that much – and then it disappeared in 2020 as “revived” economic fears weren’t all that dormant.

Coronavirus? No. Weak economy that the bond market knows didn’t improve and if there is anything to come out of the outbreak it will have been from this making an already bad situation that much worse. As I wrote on Friday:

But then the yield curve steepened back out and “the” inversion went away. The 2s10s pulled up from -4 bps to as much as +34 bps. In large part because of this, sentiment has swung entirely optimistic. All predicated on this idea of a recession scare that the US economy easily weathered with the skillful aid of Jay Powell’s rate cuts and repo operations.

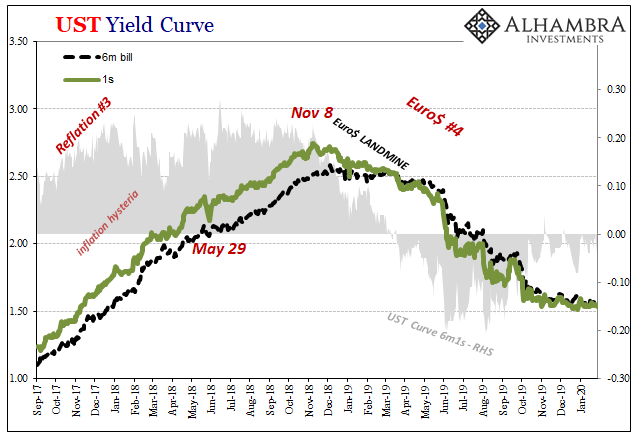

Perhaps. Then again, the yield curve “wrinkle” is back already. In those same places on the yield curve, the longer rates are below (some of) those in front of them. The difference between the 6-month bill and the 1-year, which looked like it was going to shoot positive early in November 2019, has gone back and remained underwater (inverted) ever since.

That “wrinkle” importantly between the 6-month bill and the 1-year (below) re-emerged and has been alarmingly steady since early November. A forward-looking part of the market thinking about the realistic possibility of more rate cuts over the intermediate term ahead and doing so well before anyone had heard a thing about Chinese coronaviruses.

Like any disease pathology, an outbreak hits those already in a weakened state the hardest. In truth, judging by the bond market curves, but not exclusive to them, there really was never much behind the rebound idea. If the global economy had truly been heading in the right direction, and not just another epidemic of narrative, we’d have seen substantial, material changes in the yields and curves followed by confirmation in a broad survey of surveyed sentiment and then clear uptrends in data.

“Revived” economic fears are simply concerns that are once again catching renewed notice even as they never actually went away. Since early September, the only substantial change has been the coronavirus pandemic.

Stay In Touch