In September 2012, the Federal Reserve’s third QE wasn’t the only major “rescue” of note. The Europeans had benefited from Mario Draghi’s “promise” earlier that summer but that was a little too vague. So, the various governments cobbled together sufficient backing to launch the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

This replaced two other prior “rescues”, neither of which are worth mentioning. The ESM was going to be something like Europe’s lender-of-last-resort; borrowing funds in private markets at reasonable costs and then using those funds to bailout whichever southern EU state was most in trouble at any moment. Only, with the ESM the word “bailout” was never to be used.

European politicians were concerned about the growing stigma of official action. Earlier in the same month, the ECB under Mario Draghi received approval to begin buying up government bonds (though sterilized). However, the ECB had no mechanism for placing conditions on those purchases, the ESM therefore providing the means for both combined to act like a Euro-centric IMF.

Not everyone was happy with all this. Notably, objections were raised in Germany. There is as much lingering trauma over Weimar hyperinflation in that country as there are ghosts of the Great Depression elsewhere around the world. Bundesbank officials, in particular, used the “p” word in its official criticism.

He [Bubba’s President Jens Weidmann] regards such purchases as being tantamount to financing governments by printing bank notes.

Money printing = inflation, therefore Germany says, “no way.” But what the ECB and ESM were proposing was nothing more than an asset swap. It is funny, isn’t it, how even central bankers are confused about what it is they actually do.

Then again, for Economists in this modern age “what” any of them do doesn’t actually matter. They really believe the only thing that does is what the public thinks they are doing. And if every one of you out there in these vast economic spaces truly imagines how all this financial rejiggering amounts to “money printing” then that’s what it must be – even if it isn’t.

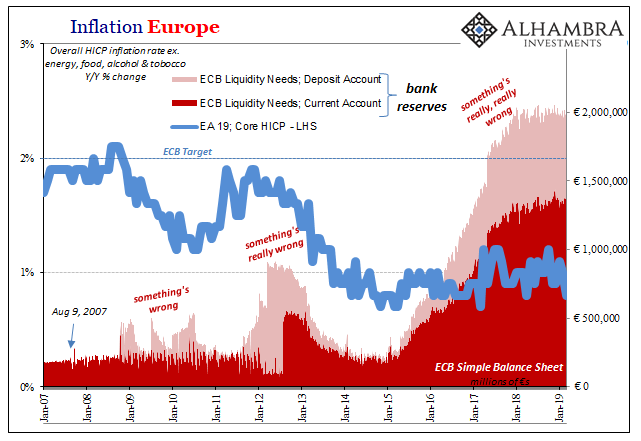

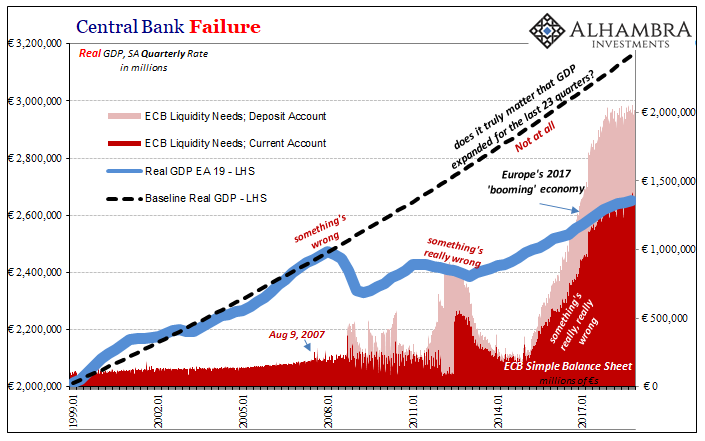

This is what the ECB was counting on, the same as what Mr. Weidmann was criticizing. Neither got it right; there has been no uncontrolled outburst of inflation nor has there been any recovery since 2012. If anything, it has gone the opposite way (leaving the ECB to un-sterilize its government bond purchases in 2015, what is commonly known as QE supposedly the real money printing out of all the official money printing options).

Ben Bernanke bragged in November 2002 how central banks have this thing called a printing press, and when faced with circumstances just like what the Europeans see above central bankers should not hesitate use it. He said:

But the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. [emphasis added]

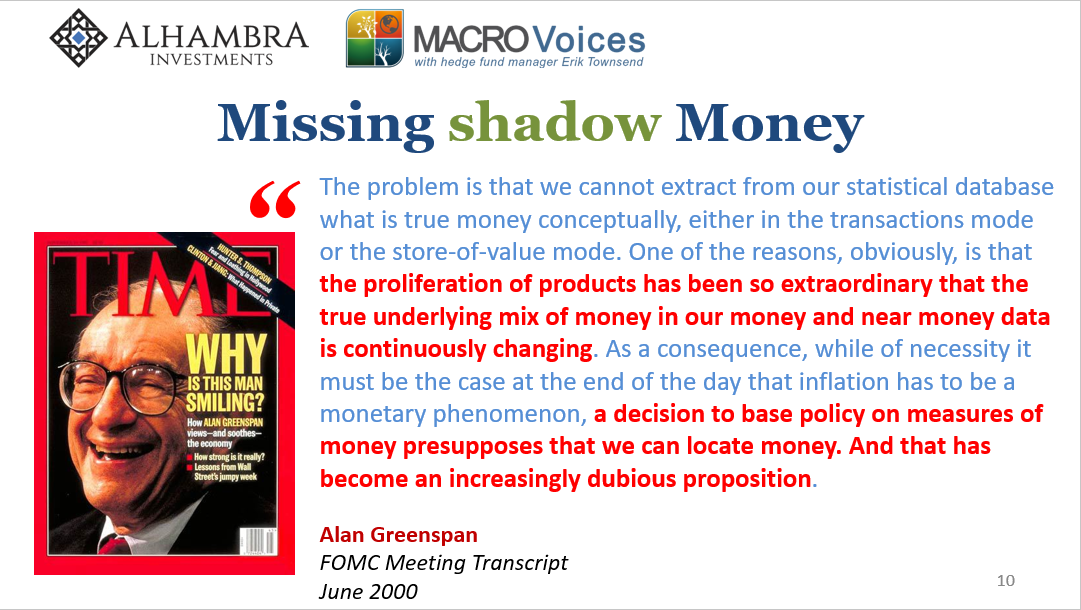

The shorter, more direct and appropriate question to ask is, why is it apparently so hard to print? For central banks, the limitation is ideological far more than anything. When Ben Bernanke was thinking on the topic back sixteen plus years ago, nobody would challenge his assertion. At least not in public. Very different discussion going on behind close doors.

This “proliferation of products” Alan Greenspan referred to was the stuff I was talking about on Friday. Short version: balance sheet capacities that the various bank participants in this eurodollar system create and redistribute largely without central bank input.

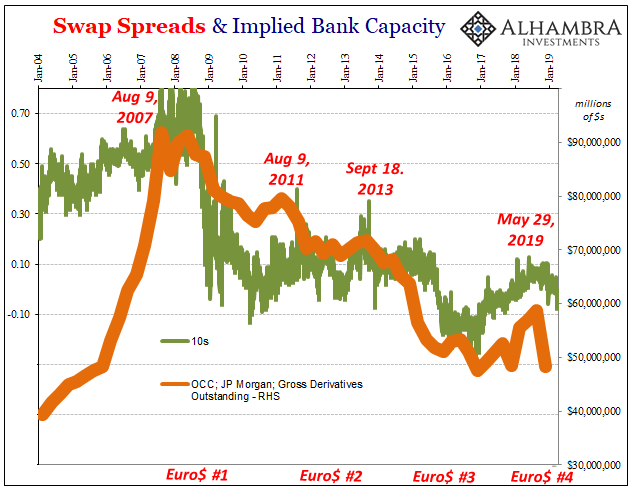

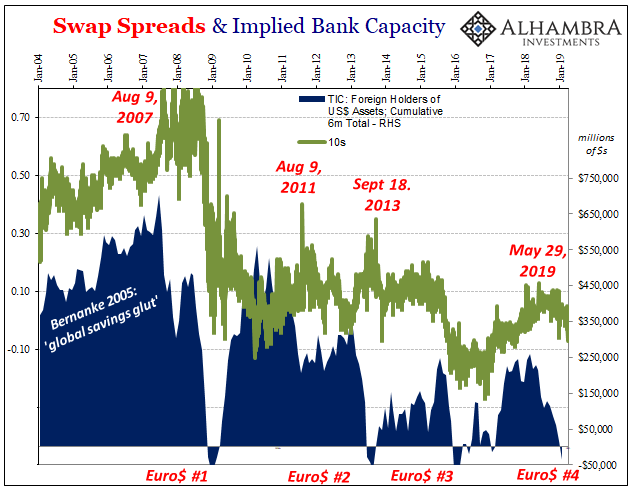

The issue of money printing is therefore one about balance sheet capacity; which, as we know in 2019, has been constrained for some time. No amount of QE seems to dislodge the stubborn constraint. Something is missing.

The natural question to then ask is, why aren’t the banks printing money? On the surface, it maybe seems just as easy. Get the banks to buy in via whatever rescue, to feel good about the world, and then just flip the switch! Maybe Bernanke can’t do it himself, but get JP Morgan’s CEO on the phone and, voila, done for him.

If only it was that easy. When we talk about what’s happened, we do so in abstract terms. Banks have been shrinking their balance sheets. Therefore, to alleviate the monetary strain we need to get them increasing their balance sheets. This is far more complicated than numbers on accounting statements.

A shrinking balance sheet isn’t otherwise neutral. Set aside any reasons why, to go along with smaller thinking these banks have made themselves literally smaller. Last week, Société Générale became just the latest global giant (formerly) to demonstrate this anti-money printing.

Societe Generale plans to cut 1,600 jobs, mainly at its corporate and investment banking arm, in an attempt to boost profits after a poor performance last year, France’s third-largest bank said on Tuesday…

For example, it plans to end over-the-counter commodity trading and reduce the size of its fixed-income arm. Associated jobs from support functions will also go, Cabannes said.

For over a decade now, these “bond trading” units have been pared back, the epicenter of mass layoffs and systems degradations within the banking sector. To the general public, even to central bankers in Europe and the rest of the world, this is just what’s to be expected in the wake of what everyone still believes was a subprime mortgage debacle. These guys need to be chastened.

Once you realize that, in the absence of an alternate global monetary schematic, we need this bond trading stuff it’s not so easy to just flip the switch; to go back in the other direction. The traders are all gone, moved on, their expertise lost as is that of their considerable support staffs and the deep systems logistics necessary for “fixed income.”

Bond trading is an expensive business, which is why it either makes a lot of money for the bank or it is the first one to fall under the axe. Repeatedly.

Since the output of bond trading is this global money, we notice the shrinking in far reaching ways. However, we can’t just turn it all back on. To ramp up operations again, assuming we could ever get bank managers back on board, it would take considerable startup costs (which shareholders have no appetite to sink in) as well as time and effort before ever contributing more actual “money printing.” When we talk about balance sheet capacity, there are literal, real world capacities to consider.

QE is the puppet show; bond trading is the real deal.

Now go back to what Bernanke said in 2002. Set aside all the differences balance sheet capacity versus central bank. On his own terms, he said the printing press made it easy because new money could be printed “at essentially no cost.”

The theory doesn’t look at all the same when that’s not true. If there are significant costs in money printing, what then?

Now ask that question properly of this credit-based money and you start to get a sense of why it’s been so incredibly difficult for so long. And why it is self-reinforcing. Banks either make money in money dealing, or they eliminate more capacity in money dealing because fixed income, bond trading, or whatever you want to call it is expensive (and regulations have made it even more expensive).

Furthermore, balance those costs against the post-Bear Stearns risks, and I’m actually amazed there’s anything left at all (only slightly joking).

The more banks eliminate from their capacity the more likely the economy will suffer but also the more likely that’s where the next round of cutting will fall. No wonder balance sheet capacity is at such a premium.

When you realize all those trading desks, the stereotypical chain-smoking Wall Street bully running the show, arrays of 90-hours-a-week traders relentlessly attached to their assigned screens, the back-office support staff sitting in countless rows of cubicles, the telephones and office space, the top-of-line computer networks complete with near speed-of-light capabilities spread across vast geographical spaces, that’s what this printing press truly is, the monetary task for economic recovery really is exponentially more complex.

Next to that, these ESM’s or QE’s seem rather silly. Pardon us Dr. Bernanke, money printing isn’t at all what you said. The results speak for themselves on that account. Talk, now that is cheap. Money is not.

Stay In Touch