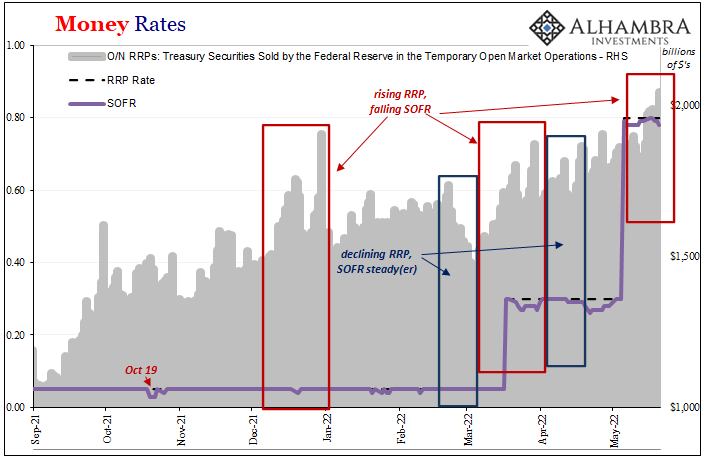

You might not know it, but front-end T-bill yields are not the only market spaces which are making a mockery of the Federal Reserve’s “floor.” There are others, including the same money number the same Fed demanded the world (or whatever banks in its jurisdiction it could threaten) ditch LIBOR over. Yes, SOFR.

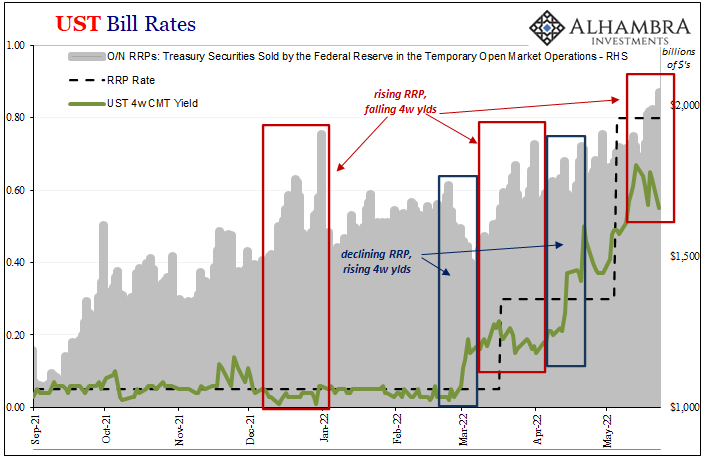

I’ve repeatedly highlighted the 4-week Treasury bill simply because it makes a direct and pretty easy-to-understand collateral comparison. As of the close today, May 23, the 4-week equivalent yield tumbled yet again, down to just 55 bps. For those keeping score at home, the current RRP “floor” is set at 80 bps.

There is no investment reason why anyone would accept less than this 80 bps return offered by the Fed at the RRP. That’s what makes the 4-week bill being so much less so powerful of a demonstration. The only reason you’d ever accept lower, let alone so much little investment reward as right now, is a shortage of collateral; a non-investment value, a liquidity premium that the global monetary system must absorb just to keep on.

Believe it or not, Friday’s SOFR was calculated – by FRBNY – to have been 78 bps. As the 4-week bill, that’s less than the RRP rate and this isn’t the first time. Since SOFR is derived from mostly repo transactions (that get reported), this simply means that many if not most of those have been going through with less return than RRP, too.

So, how do we figure a lesser repo rate?

Like the volume in the RRP, a low, now negative spread of repo rates (combined into SOFR) compared to the RRP rate at first seems consistent with the mainstream narrative about how there’s way “too much” money floating around. This, allegedly, accounts for why so much of has been deposited at the RRP and now with what must be leftover just dumped into repo pushing repo rates downward, too.

And that “too much” money is, as always, claimed to be the Fed’s bank reserves.

Nope.

I’ll get to bank reserves in a moment. First, like T-bills, conspicuously low repo rates can be and often are the result of collateral shortage. Just simple economics (small “e”):

Imagine you are a cash-rich bank while chaos rages all around you. Risk averse, absolutely, therefore you want the highest, best possible security for your cash. The best quality collateral, that is.

What if no one has any?

In other words, you’ve got spare cash and don’t mind carefully parceling it out but you can’t find any takers. Not for lack of willingness, mind you; it’s a crisis, after all, and the line is out the door. Counterparties would love to borrow every last nickel you’d offer, but they can’t because you’ll only accept the highest quality collateral in return which they don’t have and can’t get.

Thus, what happens next is the same basic economics (small “e”). You discount the price you’ll accept for lending cash, even during a panic, just to generate any return you can. Since there aren’t many showing up with acceptable collateral, you’ll go down even close to a zero interest rate if that’s what it takes.

Or you’ll take less than RRP in repo if there’s some friction (and there is) going from repo to the Fed. Either way, collateral shortage pressures counterparties to take limited return at the RRP or in a lesser repo rate.

More cash than collateral, and that’s a huge problem. Again, it may sound like “too much” money, but we know it isn’t.

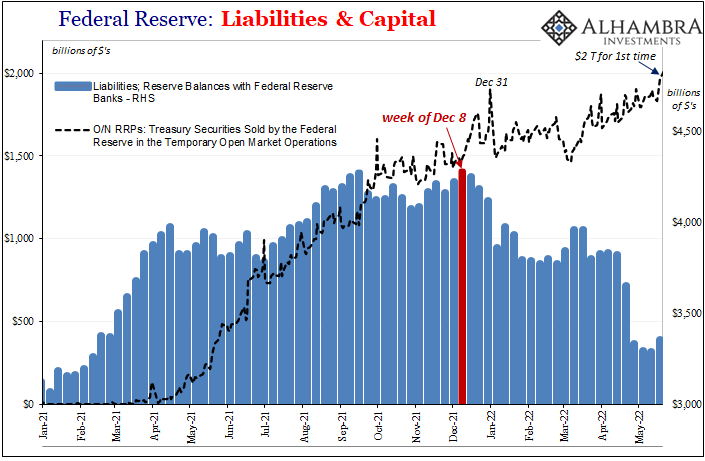

How do we know? For one, bank reserves. As all this activity is going on, systemic bank reserves available to the system (a matter of Fed policy alone) have tumbled since early December.

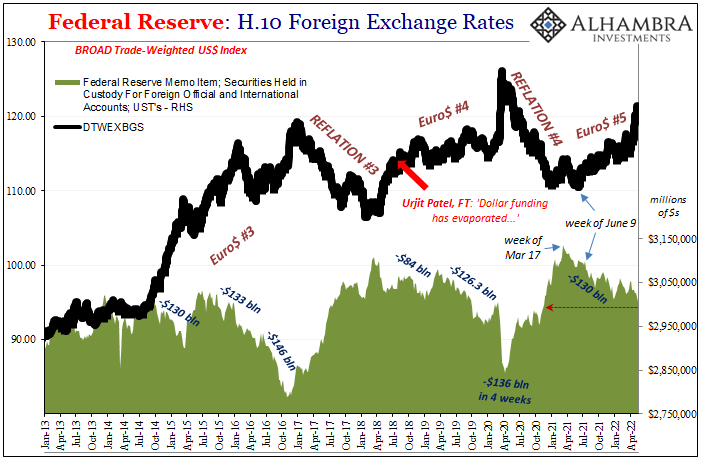

Even as the aggregate RRP balance throughout 2022 has continued to rise – reaching $2 trillion for the first time just today – bank reserves have contracted by a whopping $919 billion (-21.5%) since that previous peak nearly six months ago. The same half-year when T-bill rates keep undercutting the RRP rate, and when SOFR more frequently falls under the same, and, again, RRP use continues to reach new highs.

It isn’t “too much” of the Fed’s tokens, bank reserves; it can’t be since those have declined sharply. Rather, the entire global money marketplace (in 2022, especially) is more and more seeking the safest possible outlet and finding it lacking for lack of collateral in particular. Just imagine how much real funding must have been yanked from riskier market segments (maybe you don’t have to imagine?)

That’s why the RRP use went up in the first place, and now keeps going even as bank reserves disappear. Like repo, if you can’t find enough counterparties with the right collateral, then taking the RRP or a lower repo (SOFR) rate are your only options.

The less counterparties have good collateral, the more frequently and intensely these other things happen (lower bill and repo rates, higher RRP use). Risk aversion becomes more extreme, and all these combined show us exactly what it is and why.

I’ve argued for over a year – since the RRP first became a “thing” in mid-March 2021 – that collateral shortage not “too much” money is the only way to account for all these facts. The Fed has, inadvertently again, done us a huge favor by scaling back bank reserves to further expose this truth.

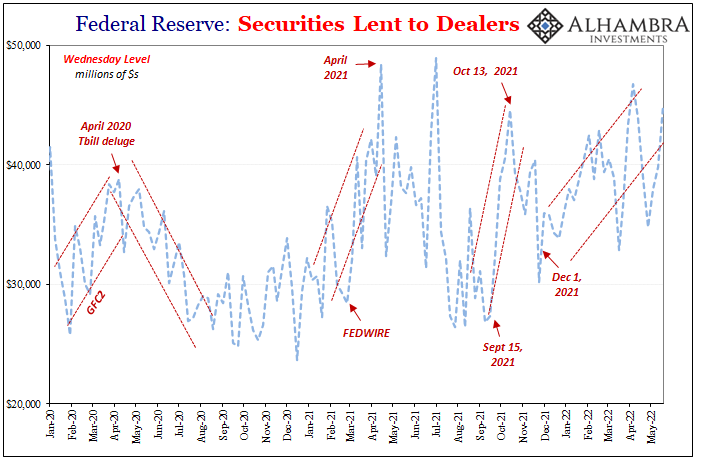

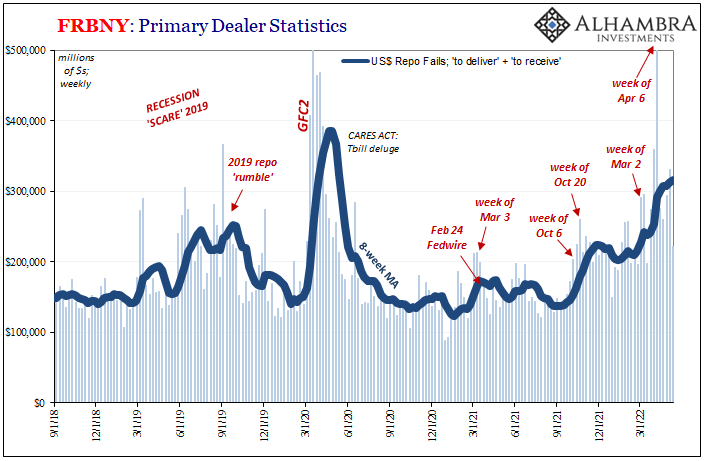

T-bill rates under RRP, the 4-week absurdly below. Repo fails. Securities lending at the Fed window. RRP use up to $2 trillion though bank reserves are down by nearly $1 trillion. Add SOFR, too.

Collateral. Collateral. Collateral.

Increasingly dangerous deflationary money of Euro$ #5, never once genuine inflation.

Stay In Touch