Finally, finally the global bond market stopped going in a straight line. I write often how nothing ever does, but for almost three-quarters of a year the guts of the financial system seemed highly motivated to prove me wrong. Yields plummeted and eurodollar futures prices soared. It is only over the past few weeks that rates have backed up in what has been the first real selloff since last year.

Is this a meaningful change?

It may seem that way in certain places. The ECB has launched a more creative QE, the Fed cut rates once and hints at more, and more than anything as far as liquidity risks are generally mentioned the US central bank also brought QT to an abrupt and unscheduled end. Perhaps these alone or in concert have saved the world from the brink which only now the bond market recognizes.

While that sounds good, events over the last 24 hours have conspired against the idea. It began late yesterday with China announcing how its economy has only sunk still further toward the “hard landing” and trading ends today with the repo market making headlines.

Again.

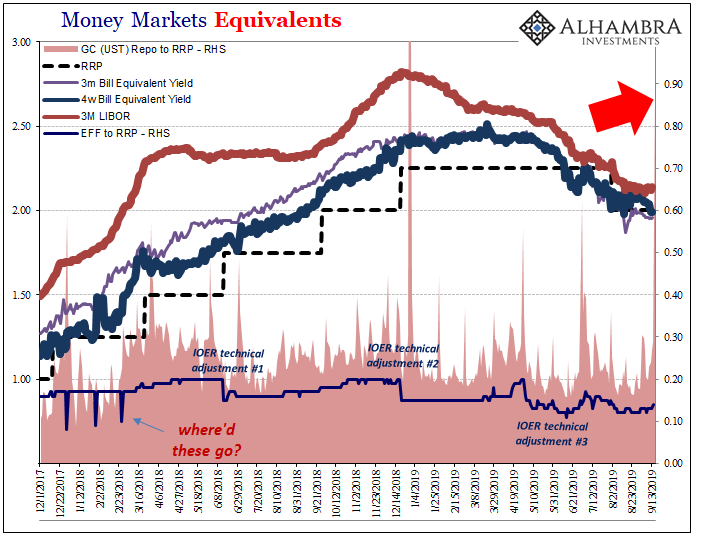

There have been several theories, additional theories, I will point out, put forward for what’s going on in repo. They are all familiar, whether money market funds or one says it is the Treasury’s General Account. Taking the latter, the way the accounting works whenever the government holds more cash that’s less cash for the economy. In the parlance of Fed balance sheet math, a factor “absorbing” reserves.

Once again, it misses the forest for the trees. What happened in repo today wasn’t in any way unique.

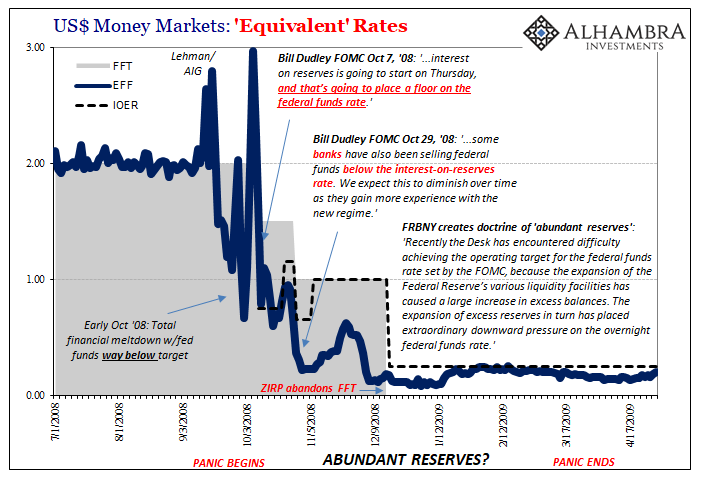

We need to back up and review some things first. It makes sense to begin with the doctrine of abundant reserves; or, as I call it, the fallacious doctrine of abundant reserves. I write that it is a false one because it is demonstrably so; the Fed says there must’ve been abundant bank reserves in October 2008 moving forward, how else to explain fed funds so far below target making a total mockery of IOER?

But that’s ultimately the point about IOER; its earliest days prove how little Fed officials know the system. Abundant reserves simply go along with that. We are asked to believe there was more than enough money available during the biggest, baddest, broadest monetary panic since the Great Depression.

Sorry, no takers here. It is such a bizarre claim on its face even before getting into any details. As I wrote a few months back:

Straight away you have to ask, what good are reserves if they are abundant and the whole world melts down anyway? According to the doctrine, you aren’t supposed to ask that question.

Therefore, the episode teaches us two very important lessons. First, there’s obviously much more to the financial picture than bank reserves. The Fed talks about liquidity in regard to them, but they must be small issue to the wider world otherwise 2008 wouldn’t have happened at least beyond October.

There’s simply no way to reconcile a monetary panic with this absurd idea of too much money or liquidity. The level of bank reserves just doesn’t correlate to anything outside the immediate arena of bank reserves.

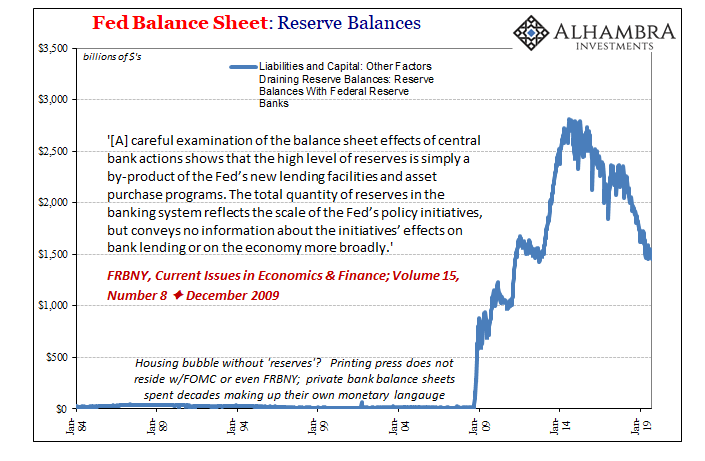

How can that be? Well, that part is actually very simple. Prior to the panic period in 2008, there were almost no bank reserves in the US system. The level throughout the entire interest rate targeting period up until late 2007 was minimal; for a system that routinely runs into tens of trillions, maybe $10 billion in bank reserves.

The global dollar system simply didn’t need the Fed; it had created its own methods and means for worldwide dollar liquidity without them.

The level of bank reserves, then, only tell us what the Fed is doing and nothing more. If bank reserves were immaterial to global liquidity conditions before the crisis, why would anyone expect that would change with the crisis? The sordid tale of IOER and “abundant reserves” only stands as more proof.

In other words, the eurodollar system spent decades effectively creating its own monetary language, a method of liquidity communication no central banker was fluent in speaking. The great conceit of Alan Greenspan’s tenure was how he claimed they didn’t need to. As I said recently in conversation with Erik Townsend and Luke Gromen:

That was Alan Greenspan’s Fed in particular saying, since we don’t need to speak the language of the eurodollar system, we’ll just raise or lower the federal funds rate and then we just expect that system will translate those inputs as necessary. We don’t need to know the monetary details, the banking system will do that for us, it will take care of what we need them to do in money on our behalf.

MacroVoices @ErikSTownsend and @PatrickCeresna welcome @JeffSnider_AIP and @LukeGromen to the show to discuss the impact of changing Eurodollar markets, the global dollar liquidity shortage and the future changes in global reserve currencies & more.https://t.co/iFqRoKCeVE pic.twitter.com/TXSqKqW2rj

— MacroVoices Podcast (@MacroVoices) September 12, 2019

In a nutshell, that was all 2008 was. But that’s not how Economists and policymakers saw it. They looked at it very differently.

In the official view, the private money dealing system broke and despite the heroic efforts of our best and brightest they were thwarted by a no-win situation. Realizing that in December 2008, authorities turned their attention to making sure a really bad crisis didn’t become outright catastrophic. Thus, ZIRP and more so QE.

What QE supposedly represented in this alternate universe was a handoff: going from A to B, from the private money system which broke down to a more public-based one where those money dealing functions were increasingly absorbed by the Fed’s balance sheet expansion. Bank reserves in this other context are a liquidity substitute for the private system’s former monetary contributions.

Bank reserves, however, were and are not a substitute – as should’ve been abundantly clear in late 2008. They are a completely different language, at best an asset swap (and arguably a harmful considering effects on repo collateral flow and availability).

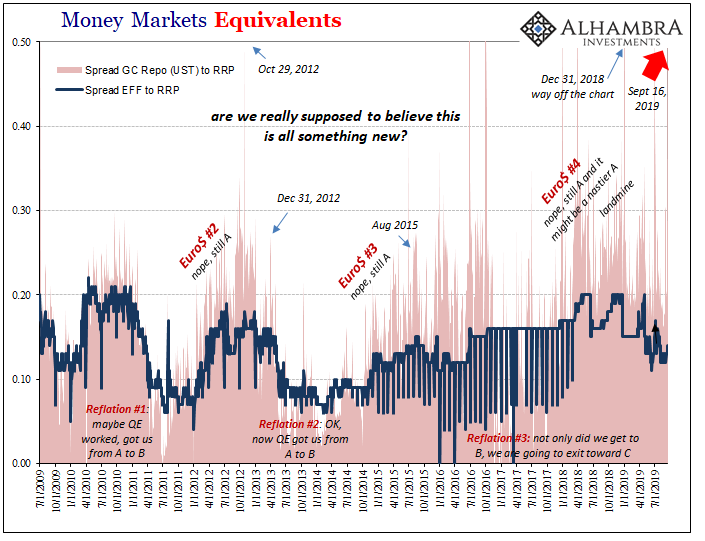

But officials persisted. They first looked at Reflation #2 in 2014 as successful completion of A to B and began contemplating their exit strategies accordingly. In broad terms, going from B to something like a C, with A not really being possible. It was supposed to have been a handoff from public back to private but a different sort of private system (C) not quite like what it had been before (A).

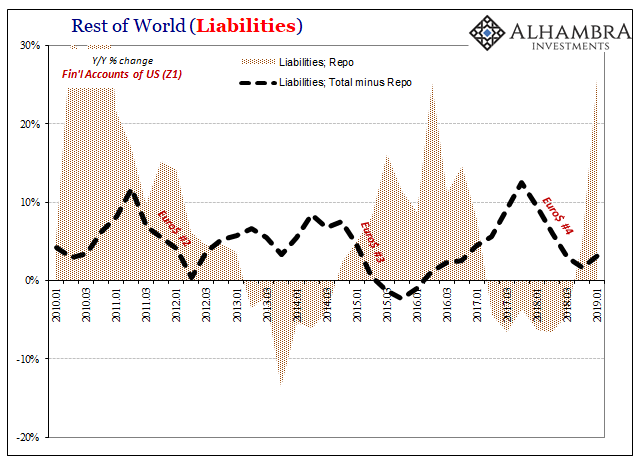

Euro$ #3 interrupted, of course, proving yet again how officials have no idea what they are doing. They blamed temporary factors and “overseas turmoil” and then misread the situation of Reflation #3 as far more than it was; making a liquidity mountain out of the smallest molehill (against all contemporary, real-time advice of the bond market curves).

The whole point of QT was to move from B to C; to wean the global liquidity environment off of the Fed’s presumed liquidity capacities and to hand it back to…someone. The FOMC began to reduce its balance sheet again, the level of bank reserves dropped and what was supposed to follow was no one noticing either of those things.

If QE had been at all successful nobody would’ve cared one bit about QT. The resilient and rebuilt financial capacities, as Janet Yellen said of them, should have picked up the slack as the Fed withdrew. And because the economy was booming, they said, there was absolutely no reason to believe otherwise. C wasn’t just going to be good it was going to be fun again.

Except, obviously, that’s not how it has gone. Almost from the very beginning we’ve been asking the same question: where are the dealers? The Fed has everyone prepared to leave B and to head toward C except the further they go the clearer it becomes that C is somehow empty. Thus, the unscheduled, abrupt end of QT; stuck at B.

But we aren’t actually stuck at B. If you are one of the central-banks-are-central people, that’s what it looks like when in reality the global system never for a minute left A. And that’s simply why the more policymakers move toward C the more it looks like A.

What went on in repo today has all new excuses but the same repeating results. For the mainstream, this must be something new because the Fed changed its policy (trying to get to C). It isn’t anything new; it’s the same problems as we’ve seen countless times. Euro$ #4 is still A.

To address what it sees as the problems heading toward C, the Fed will now almost certainly implement a standing repo facility even if it doesn’t have any real idea why; after downplaying the need the whole time. Despite an end to QT and rate cuts, nothing has changed especially in the repo market.

I told you it wasn’t QT – because bank reserves are irrelevant. They always have been. Central bankers just don’t speak the right language.

The real hard truth about A is simply that it hasn’t been a straight line. There were times when it appeared the system had made it to B, but that was only these temporary and mild reflationary periods interspersed throughout the last decade. After enough time, we just go back to A. Maybe even nastier.

Stay In Touch