I completely understand the confusion regarding bank reserves. I really do. It’s easy to believe they are money because that’s what you’ve been taught from Day 1. Not only that, the same message is carelessly reinforced in the media every single time QE or any LSAP is referenced. Bank reserves are the aftermath of money printing, therefore = money.

That was never really the case, however.

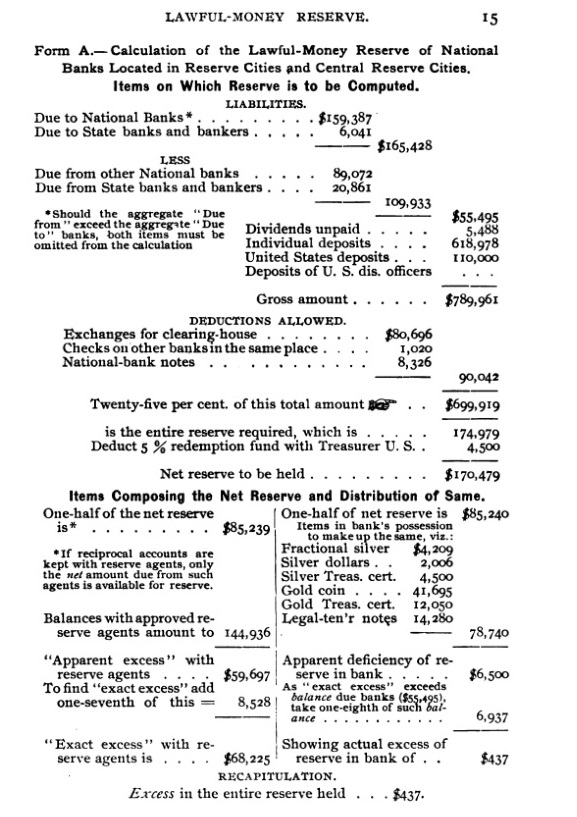

George M. Coffin, perhaps the pre-eminent banking expert of the Gilded Age, wrote several books on the topic of banking. He was at the time employed by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the chief regulator for all national banks. By the mid-1890’s, he had risen to Division Chief of OCC’s Division of Reports. It made him the head supervisor of all national bank examiners.

What he left us in his books is a precise glimpse of banking at that time. What you see above is the traditional relationship between actual money and reserves. The bank shown above, a reserve city bank, was required to hold half its obligation in the form of actual cash in a vault. The other half, conceptual reserves if you will, were primarily made up of correspondent balances (“balances with approved reserve agents”) with other reserve city or central reserve city banks.

These were functional deposits that arose out of necessity of an increasingly nationalized economy – a national payment system. And it was this system which often spread contagion from one section of the country entertaining deposit flight to others.

In Coffin’s example shown above, if the bank in question had been subject to a run, say, on its holdings of gold coin (as had happened to a great many national banks in the Panic of 1893), it wouldn’t take much withdrawal for the bank to fall below statutory requirements. To anyone paying attention, that would propose a shaky bank in fact rather than just in rumor and therefore exacerbate any flight.

How would that bank be able to remain in business?

It would either call in loans, liquidating them for whatever cash it could obtain often at firesale prices, or it could convert its correspondent balances by requesting cash payment (specie). That, of course, would reduce the reserves of the correspondent bank, creating liquidity problems for it, and so on and so on.

The role of the central bank, in this case the Federal Reserve, was to be able to create reserve balances outside of specie. A central city bank, the precursor idea for primary dealers, could deposit collateral with its local Fed branch and in turn be sufficiently supplied with “bank reserves” of the kind we are familiar with today; a ledger credit on both the books of the Fed branch as well as satisfying the statutory reserves of the central reserve city bank.

In theory, a central city reserve bank could run down its cash holdings to nothing and still be in compliance. And to other correspondent banks on its same level, they would accept these reserves as like cash (the forerunner of modern interbank practices).

In this case, the run is stopped at the local bank. It may even survive as the local depository receives its cash from its correspondent who then replaces that cash with these “bank reserves” from the Fed. Everyone is now in compliance, and the net effect is merely more specie (money) held outside the system (hoarding). The “bank reserves” are not money but a legally authorized substitute to satisfy these reserve requirements.

In reality, the banking system never needed a central bank to perform these actions. Central city reserve banks formed trade groups and clearinghouses that did essentially the same thing (using clearinghouse certificates rather than formally “bank reserves”). The record was spotty (the Chicago clearinghouse, for example, was never really threatened during the Panic of 1907 while the NYC clearinghouse was if only because the latter forbade Trust companies from participating) because a run is a dynamic intrusion upon a highly bureaucratic framework.

It wasn’t any better for the Fed, either (1929).

So, how does this work under the modern, 21st century QE arrangement?

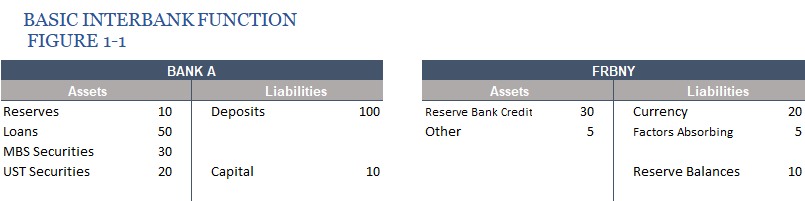

Before we begin, let me be clear that my examples unlike George Coffin’s are highly stylized and therefore omit (for the sake of clarity in illustration) real world complications and complexity. One of those, to begin with, is how the central bank makes decisions based on non-economic considerations that are often, again, bureaucratic in how they are carried out (economists call this a friction). For our purposes, we will merely assume the central bank (FRBNY) is purchasing the “correct” amount of securities.

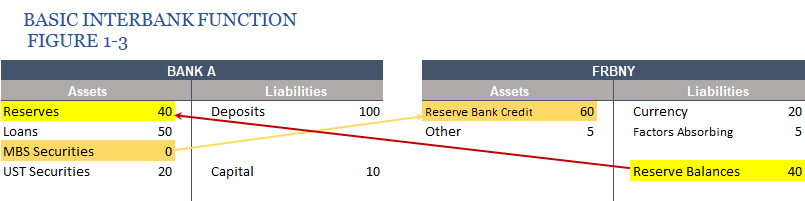

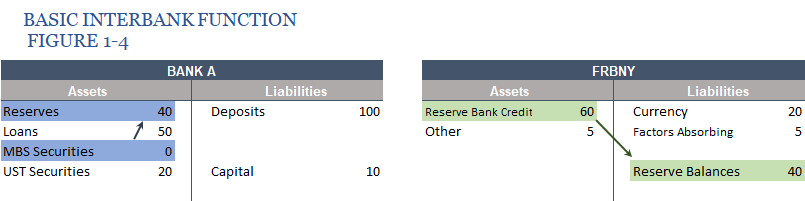

Central bank accounting is also different in that it is quite simple. If it purchases an asset, that increases the balance under “reserve bank credit” on the asset side and if nothing is done to offset the purchase (sterilization under “factors absorbing”) the effect is an increase in “reserve balances” as nothing more than a remainder. These are the bank reserves we’ve heard way too much of for far too long.

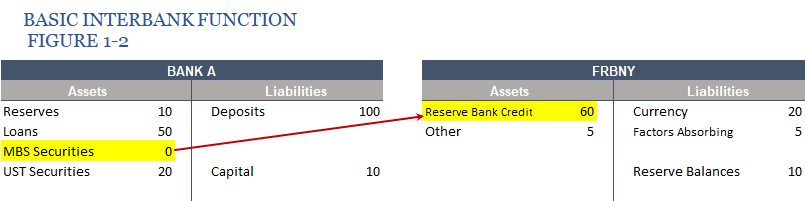

Under QE, the Federal Reserve via its New York branch purchased MBS and UST’s. We’ll start with MBS because that’s where the crisis largely registered. As noted above, the MBS securities are transferred from Bank A and stationed in FRBNY’s Reserve Bank Credit (SOMA), raising that balance in this example by $30 equal to the deduction from Bank A’s MBS holdings.

Assuming no sterilization, the total balance of bank reserves rises by the same $30. For Bank A, they are also credited $30 but now as “reserves.”

That’s all straightforward accounting. The real issue with QE, or rather their byproduct, is what happens next versus what is supposed to happen next.

On the right side, the central bank has increased its balance sheet size (LSAP) which then creates a lot of additional bank reserves (again, nothing more than a remainder). That is interpreted incorrectly as money printing.

On the left side, all that has happened is Bank A has switched one form of asset for another. The original asset, MBS, used to be considered risk-free but during the financial crisis it came to be viewed very differently (though not, as commonly believed, because of credit risk and subprime). In that sense, QE might have done some good in removing “toxic waste” from Bank A’s roster of assets and replacing it with a risk-free one drawn directly from the central bank.

But in reality, by the time the Fed was purchasing MBS the “toxic waste” issue had already been resolved. As I will endeavor to document in painful detail in the upcoming Eurodollar University Season 2, FAS 157e, FAS 115a, FAS 124a, and EITF 99-20-b (the OTTI proposal) had already effectively rendered the issue largely moot. In case you are not fully versed in accounting standards, these are collectively the so-called suspension of mark-to-market.

QE’s real purpose was largely twofold. The first was in trying to manage expectations which central bankers were more than happy to let you believe this was all money printing. If you thought bank reserves amounted to that, then you might act in anticipating all that “money printing” was going to have stimulative and even sharp inflationary effects. You might then pull forward purchasing activity, or, if a business, hiring and production before the expected higher costs arrived.

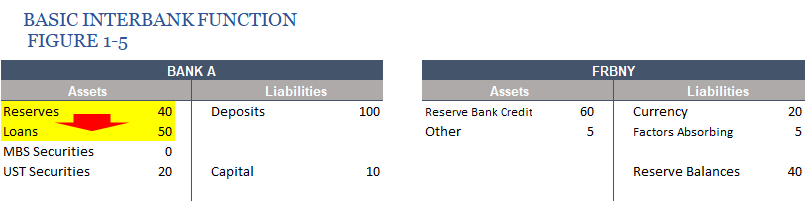

The second channel is as you see above in Figure 1-5. Having substituted MBS securities for a reserve asset, policymakers expected that Bank A would then seek to further convert those reserve assets back into a working portfolio of non-toxic securities. The policy asset swap was meant as the first step to a second asset swap, the latter of which into risky securities.

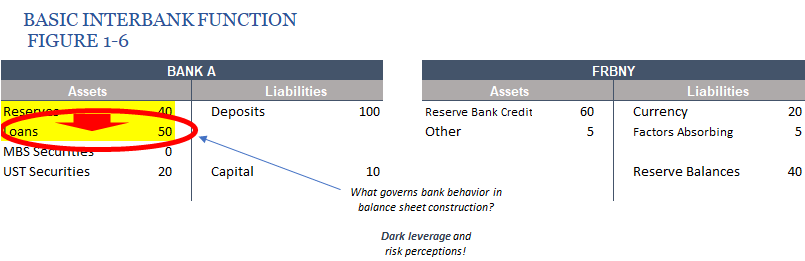

That never happened, or at least not to any substantial degree that created legitimate economic success. Some have argued that the payment of interest on those excess reserves (IOER) was the reason banks chose not to take the next step. It’s an argument that has been thoroughly disproved, however, starting with IOER’s contradictory behavior during the crisis, and then being fully tested by the ECB at negative rates long after it was over (I won’t add anymore to this here, I’ve covered it many times before).

The “clogged transmission mechanism” of QE through bank reserves was the usual balance sheet construction requirements that authorities pay no mind to; all that dark leverage stuff that banks unlike policymakers cannot ignore. Among those are the often derivative techniques that after August 2007 became in much shorter supply, meaning that it was far more difficult to construct a balance sheet in the way it had been done up until that point.

Beyond that, the governing dynamic behind all of this is risk/return. An elevated perception of risk won’t be altered by the simple swap of one risk-free asset for another. In other words, the increased balance of bank reserves as a result of all these QE’s was never an increase in effective money – at the end of the day, what was required was the stuff that animates bank balance sheet assembly, the stuff the central bank doesn’t possess but that acts like money in every way bank reserves are not.

In short, bank reserves are nothing unless Bank A turns them into something. That “something” includes other forms of money dealing. All the things that go into that action are what counts, not the reserves. That is the dollar shortage in a nutshell.

Part 2 is here.

Stay In Touch