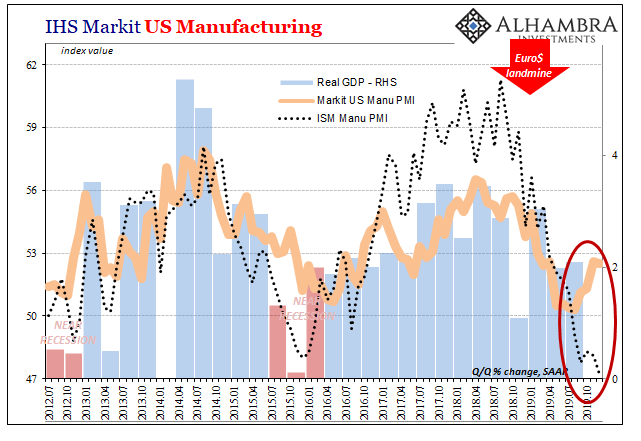

Yesterday, IHS Markit reported that the manufacturing turnaround its data has been suggesting stalled. After its flash manufacturing PMI had fallen below 50 several times during last summer (only to be revised to slightly above 50 every time the complete survey results were tabulated), beginning in September 2019 the index staged a rebound jumping first to 51.1 in that month.

Subsequent months of data had continued the trend. By November, the PMI registered 52.6 and solidly on the upswing. The trend was expected to continue in December, but both the flash and now the full reading have stuck at 52.4.

One month obviously doesn’t make any kind of trend, nor by itself indicate anything conclusive. But the somewhat disappointing lack of follow through toward a more developed rebound is becoming more consistent with other data around the rest of the world – as well as those manufacturing PMI’s developed by other outfits.

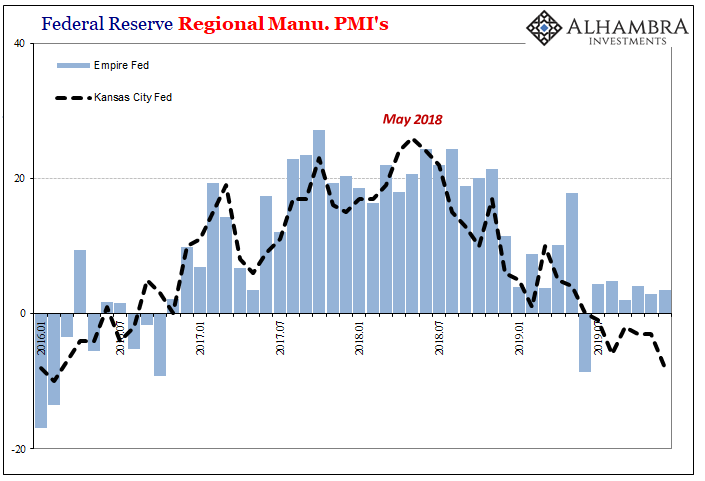

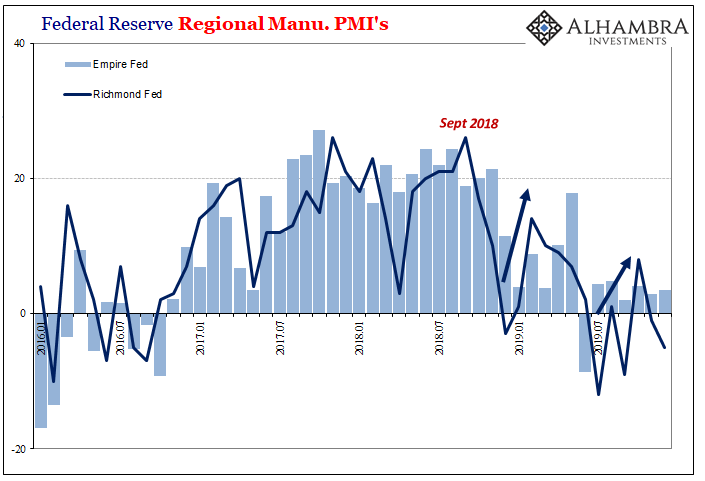

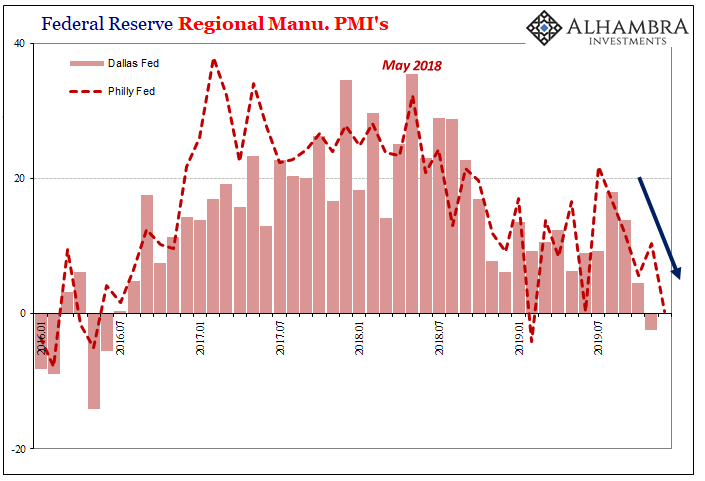

As noted last week, the Federal Reserve’s various regional manufacturing surveys were projecting a different sort of condition than Markit for their constituent parts of the whole economy. Taken together, the lack of upside was noticeable.

These figures are far from definitive, of course, but the majority of the data sets are now at odds with the idea of rebound – one that is supposedly getting stronger. Even Dallas and Philly are heading in the wrong direction (again), suggesting instead renewed difficulties in domestic production (which is consistent with more recent data showing seriously flagging US imports).

Even the regionals that had been on sort of an upswing – before the one projected by Markit – have since indicated a return to conditions more like retrenchment. Both Philly and Dallas have noticeably sunk over the last several months.

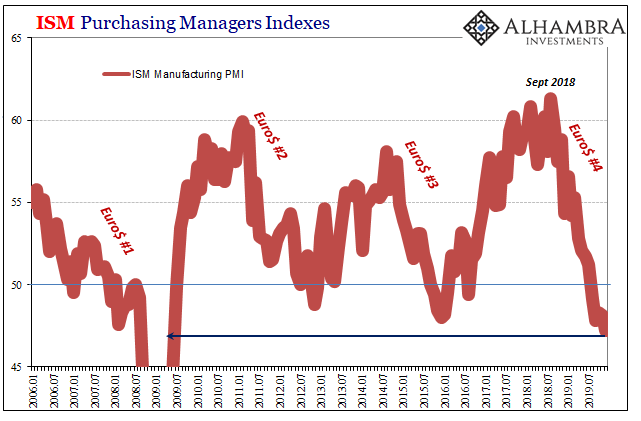

The Fed’s regional surveys have had far more in common of late with the ISM’s Manufacturing Index. Unlike Markit, the ISM never really did pick up on even minor renewed strength. Factoring monthly variability, the extent of any upturn in this original PMI was limited to just one month (October).

After rising as high as 61.5 in August 2018, by this August 2019 it was under 50 for the first time since Euro$ #3. But unlike that last “manufacturing recession”, the ISM Manufacturing PMI kept falling further – reaching as far down as 47.8 the following month in September. That was the lowest since 2009, and sparked all sorts of confusion (Jay Powell keeps saying the economy is strong) and uncertainty.

The smallest of rebounds in October, up just half a point, was followed by a slightly lower number in November (48.1). Today, the ISM reports that its main manufacturing gauge is down again and below September. At 47.2, this is now the lowest since 2009.

Just like the financial media wrote about a boom that didn’t exist (and sure didn’t last), most people will be surprised by what seems to be a rebound that doesn’t, either.

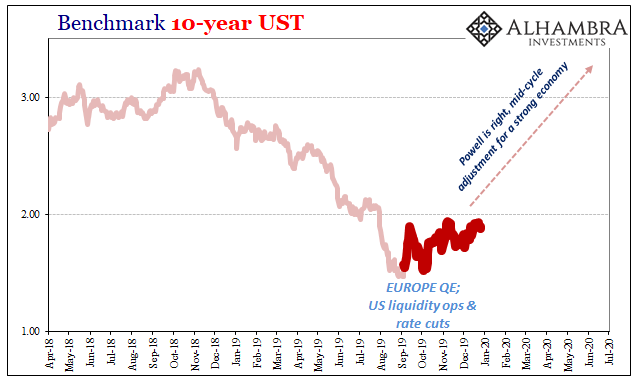

Much of it stems from a misunderstanding and misreading of the bond market (no surprise there). It was last year’s plunge in bond yields which eventually became an inverted in yield curve in the one place people sort of pay attention to. Thus, for nearly all commentary the bond market must have been signaling imminent recession.

Then, seemingly out of nowhere, yields rose and the curve un-inverted (in the one place people sort of pay attention to). If the one had been a recession warning, then its disappearance was taken to mean “all clear.”

Not just interpreted, but written about as if the bond market had definitively concluded the world was mending. Markit’s PMI data particularly in US manufacturing seemed best to fit the idea so it was widely used as more evidence for it.

But that was never really what the message from the bond market. For the record, the curve had inverted all the way back late in 2018 – not as a recession signal but as a warning the global system, economy and markets, were already in the process of reverse. That might (still) mean outright recession in the US or elsewhere, and it might not.

What the yield plunge signaled was less definitive, a statement about risk. The risks had swung around (not at all “unexpected”) to come down all on the bad side. What small chance for an economic boom in 2018 had disappeared (the landmine), globally synchronized growth replaced bit by bit with eventually this globally synchronized downturn.

Rather than foretelling its end, the bond market since September (as well as some calculations for the dollar’s exchange value) have done just what markets always do. The way down in yields (and up in dollar) was nearly a straight line; the line was, as is typical, broken. The market has gone into a “wait and see” mode that in terms of past versions is much less optimistic.

I’m quite surprised the 10-year UST, for example, hasn’t been able to break above 2% (I’m actually shocked it hasn’t yet retraced to 2.25%). That suggests, though yields have backed up, there remains far more of summer’s pessimism than any renewed conviction for optimism.

Outside of Markit’s US PMI’s, for a few months anyway, the data on manufacturing (where all of this begins) keeps reminding bond investors why. The ISM’s December 2019 number is in keeping with a potentially nastier Euro$ #4 that might even mean a domestic recession. It might not.

The risks are on the downside, as is the balance of data, whatever that might ultimately mean.

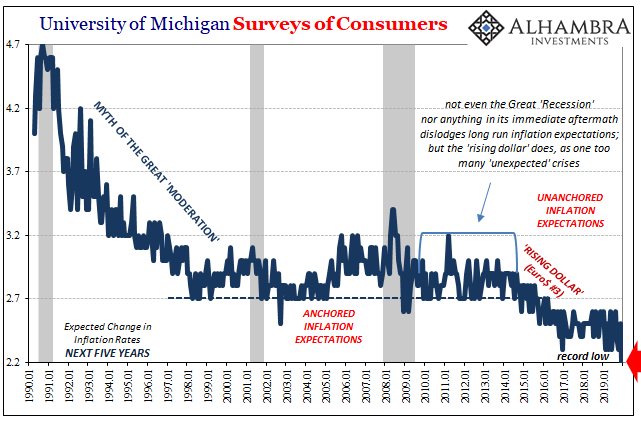

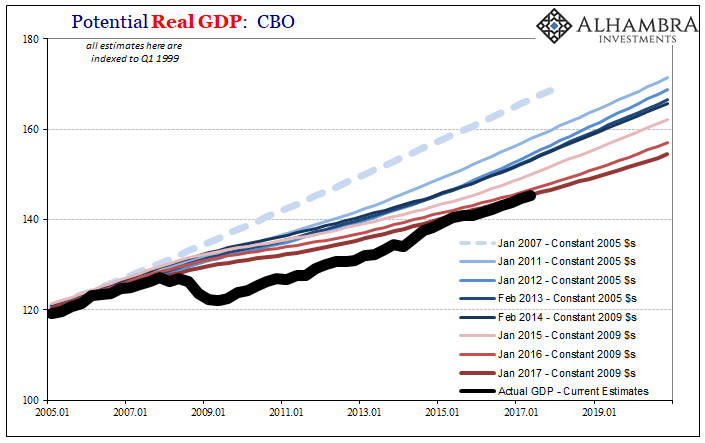

More importantly, far more importantly, it already means a significant and sustained globally synchronized downturn that the world just cannot afford. Rather than think about this in terms of the potential for another crash or Great “Recession”, the real danger lies in how this again confirms the whole world isn’t just on the road to becoming Japan it is actually quite far down that road.

Stay In Touch