There wasn’t a lot of economic news last week but it was largely as expected and seemed pretty good. Job openings rose, there was no rise in jobless claims even after the large layoffs in the government sector, and the inflation reports were better than expected. What’s not to like? We didn’t get any big moves in bonds or currencies in response so market expectations regarding growth and inflation were essentially unchanged. So why did stocks sell off another 2.3%?

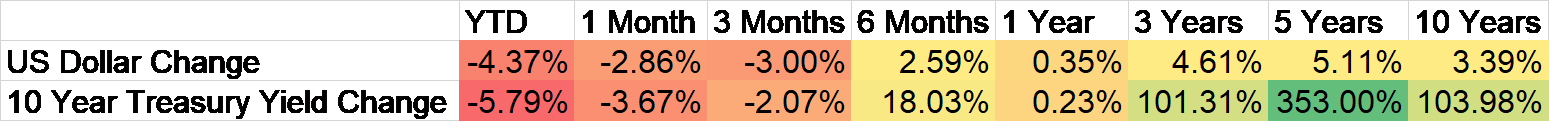

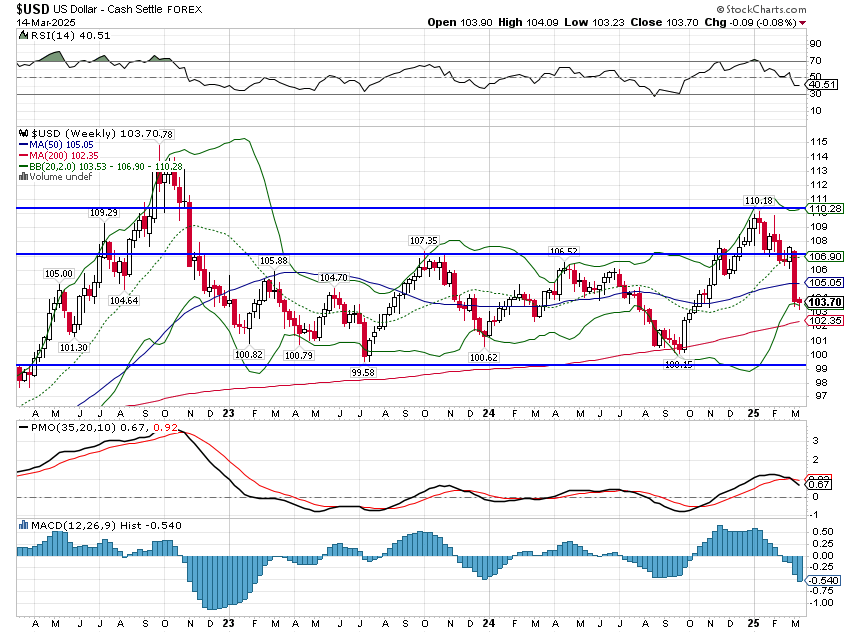

Stock prices are correlated with economic growth over the long term but there’s more to stock prices than just how the economy as a whole is doing. I pointed out last week that, despite the recent correction in stock prices, the outlook for the economy hadn’t really changed all that much. Interest rates have fallen somewhat but are well within the range which they’ve traded for the last 36 months. Likewise, the dollar, which has come down from its post election highs but is still basically unchanged over the last 1 and 3 years (up 0.35% and 4.6% respectively). Ultimately, stock prices are a function of earnings, but earnings are not just a matter of how fast or slow the economy is growing.

Markets are made up of millions of traders and investors, all making judgments about the future based on widely shared information and their own beliefs. The people who make up the market have different political opinions, different ethnic and cultural bonds, come from a wide variety of backgrounds and have different levels of experience – some old timers, some just starting out. Some are privy to information that isn’t public, be it knowledge of future government policies or corporate takeovers. Some large hedge funds, mutual fund companies, and private equity firms have access to data that you and I can’t possibly afford, although based on their collective track records, it doesn’t seem to give them much of an edge. All those people making their independent decisions is what sets market prices and gives you, possibly, a view of the future.

The market is like that old carnival game where, if you come closest to guessing how many balls are in a container, you win a prize. While your guess or any other guess might be wildly wrong, the average of all the guesses will usually be pretty close to accurate. Markets are filled with guessers, some of whom will be wildly wrong, but the end price set by the market will reflect a collective guess about the future and it will usually be pretty accurate. That isn’t always true and at times the wisdom of crowds turns out to be pretty unwise. Mortgages were obviously mispriced before the financial crisis of 2008. Dot com stocks were obviously over priced at the turn of the century. Tulips selling for the equivalent of a house in 1630s Holland was pretty crazy and obviously wrong. So, yes markets get things wrong. But they are more accurate than anything else we have and adjust in real time to reflect new information. It is, as I’ve said many times in the past, the best view of the future you will ever get.

Markets are trying to price in a lot of potential change right now but information is limited so the range of potential outcomes is wider than normal. That’s why we are seeing big swings in stocks and until some of the uncertainty is relieved, volatility is likely to remain elevated. Think about how the market has to sort out the tariff issues. Tariffs are border taxes paid by the importing company; it raises their costs. Their response to the tariffs could take several paths. They could:

- Raise their selling price – consumers pay

- Eat the cost themselves and reduce their profit margins – shareholders pay

- Extract a discount from their supplier – exporter pays

- Invest to become more efficient and reduce headcount – labor pays

Companies will try to raise prices but with consumer confidence and sentiment in the toilet right now, price hikes are probably just going to reduce volume and profits. They will do everything they can to avoid the second option but if exporters won’t share the tariff cost (and China isn’t interested), their only options are 2 and 4. So how does the market think this will work out? Well, since growth expectations (interest rates) have fallen but not by much, the market doesn’t expect a lot of layoffs (option 4) which would hurt economic growth. The market also doesn’t expect price hikes (option 1) because market-based measures of inflation expectations have been falling since mid-February. With exporters from other countries unlikely to cut prices, that only leaves option 2 which leads to reduced profits and explains the drop in stock prices.

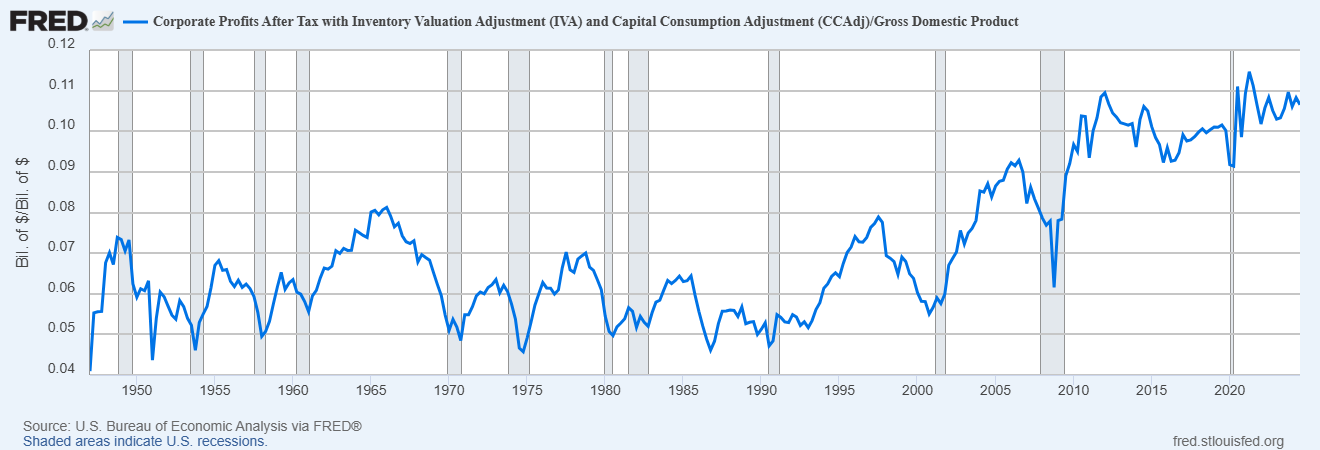

The bad news for stock investors is that corporate profit margins are probably going to come down. The good news is that margins are near all-time highs so the damage might not be too severe. And frankly, if you assume we need to stabilize our fiscal situation – and I think we do – then corporate profits were always going to be a casualty. Corporate profits are a function, to some degree, of the fiscal situation. If you loosen fiscal policy, by spending more or cutting taxes, you will get more growth and more corporate profits. If you tighten fiscal policy, you will get slower growth and less corporate profits. The long-term outcomes of different fiscal choices are likely very different but the short-term impact is pretty predictable.

Corporate profits as a % of GDP

So why are stocks still selling off if the economic outlook hasn’t changed much? Every time President Trump changes his mind about tariffs, to make them higher or lower or broader or narrower, on one product or all, investors have to adjust their view of corporate earnings. Then, when retaliation hits – as it always will – they have to recalibrate again. Until the tit for tat, back and forth on tariffs ends – if it ever does in this administration – future earnings are as predictable as Trump himself.

Environment

There was almost no change in the dollar or interest rates last week. The market seems to believe that cutting corporate profits won’t hurt economic growth but long term that is probably wrong. Lower corporate profits will mean less capital investment, slower productivity growth and therefore slower economic growth. But it will take time for that to happen and the market is probably pricing in some probability that the tariffs don’t last. Thus we get a small markdown in growth expectations rather than a large one.

The dollar was unchanged on the week and continues to trade in its old range. For a variety of reasons I believe the dollar will ultimately exit this range lower but for now I think you have to assume it will stay in the range.

The 10-year yield was down 9 basis points last week and is also well within its prior range.

For the last 36 months, interest rates and the dollar have been remarkably stable as has economic growth. How it was achieved, through large deficits and high federal spending, was not sustainable so some change was due. Whether the current administration’s approach will solve our problems is something markets will sniff out long before you or I do. Personally, I think tariffs cause more problems than they solve – and that may be the understatement of my career – but I’m only one guesser.

Markets

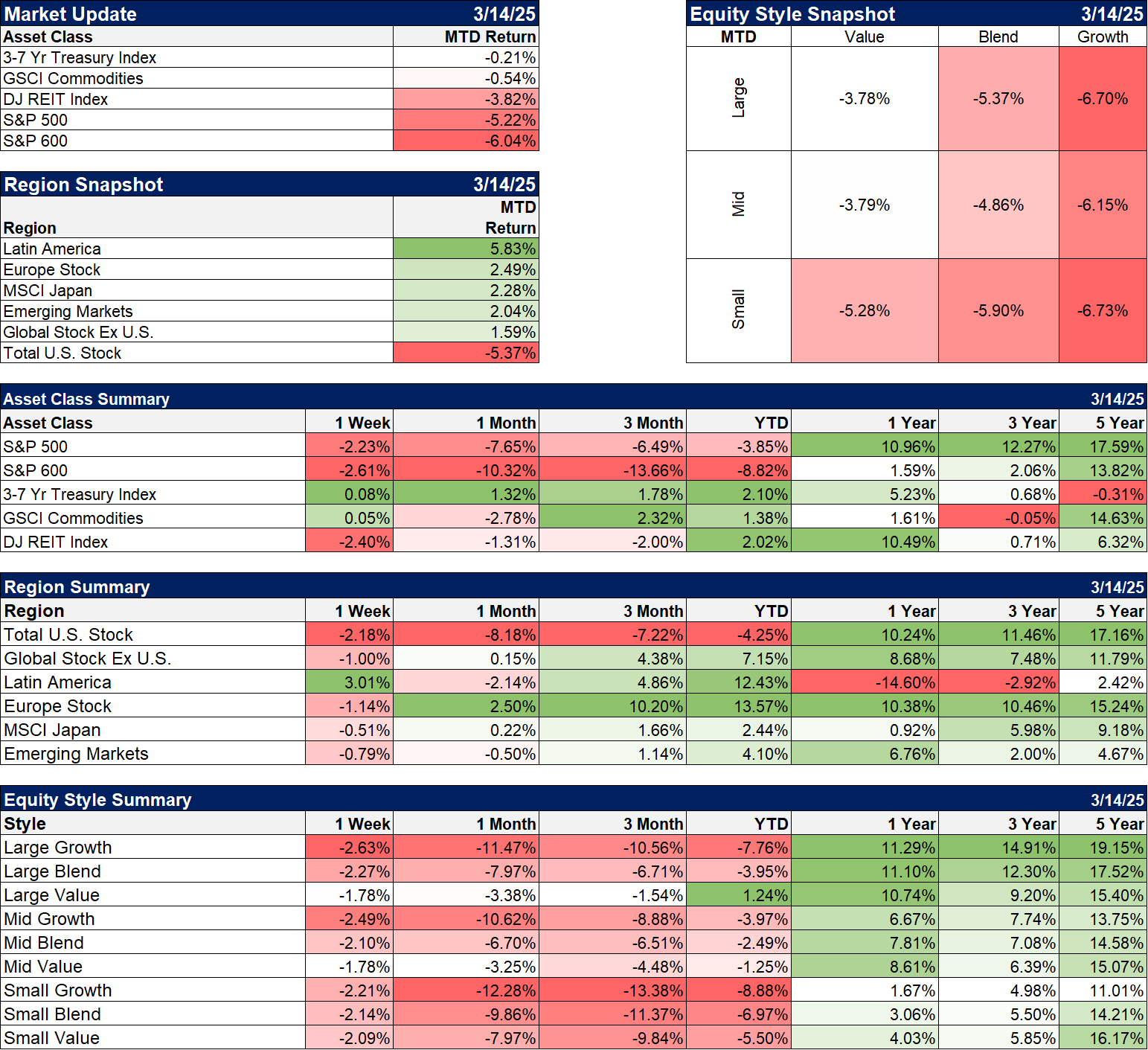

Stocks took another hit last week but bounced hard on Friday. Sentiment had gotten so negative by the end of the week that a bounce was almost inevitable but I don’t think I’d get in a rush to buy yet. Market sentiment is negative in polls and consumer sentiment is lousy but it isn’t fully reflected in the markets. Put/Call ratios spiked on Thursday but not to levels I associate with a bear market bottom. Of course, this isn’t a bear market so maybe that was enough to mark a short-term low in a bull market – assuming that’s where we still are.

Value stocks outperformed again last week as they have since the correction started. Small cap stocks continue to underperform but also continue to offer the best values in the market.

Bonds and commodities were up slightly on the week but not enough to matter. There does seem to be an underlying strength to commodities though. Even though the index was just up slightly there were multiple commodities with big upside moves including: copper (+4%), platinum (+3.2%), gold (+3%), gasoline (+1.6%) and palladium (+1.5%). Natural gas was the big loser, down 6% on the week, but up 12.7% YTD.

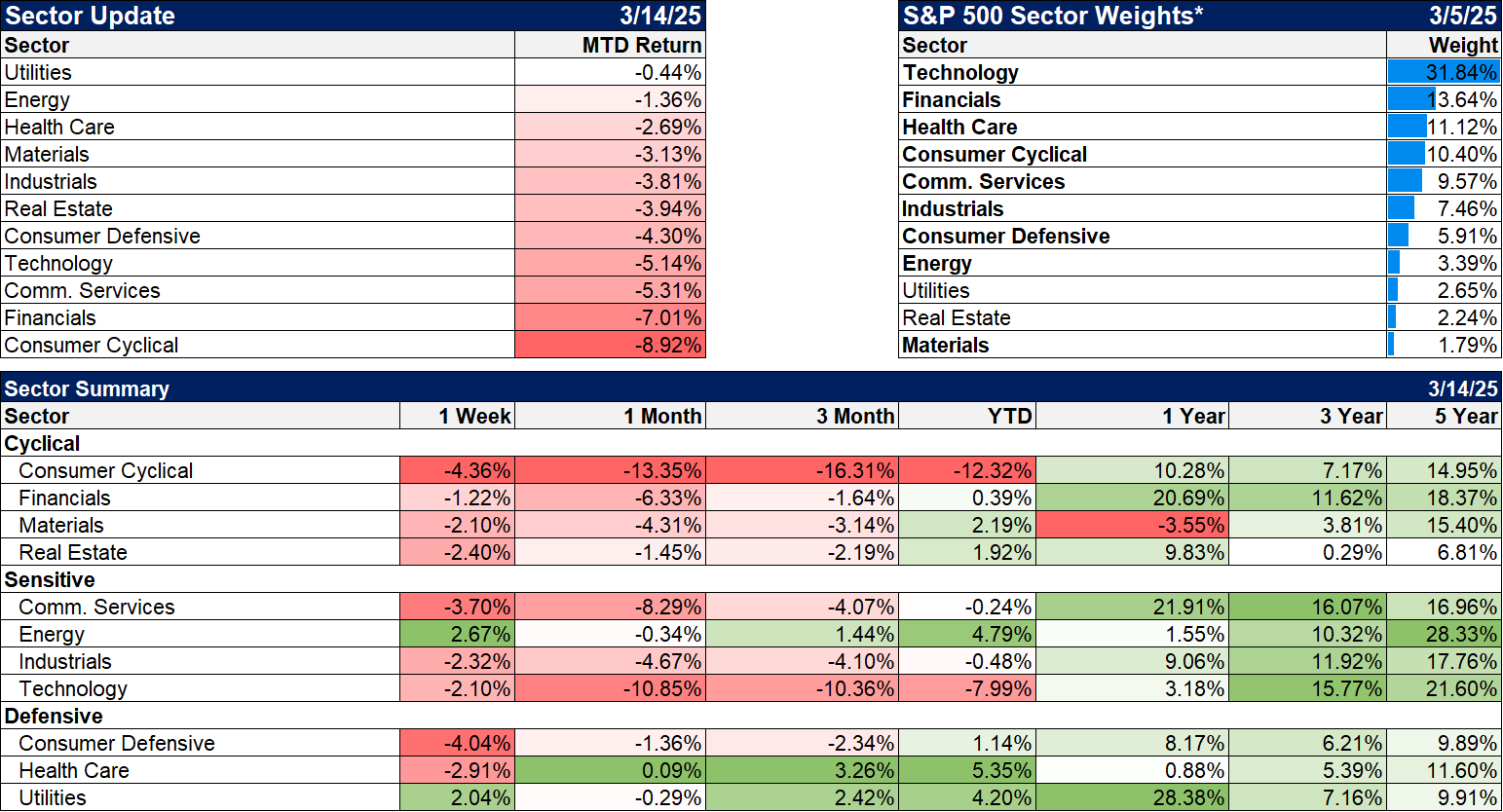

Sectors

Energy and utilities were the sole winners for the week. Energy is a bit of a surprise as crude was basically flat and nat gas was down big. Utilities are generally thought of as defensive but the AI hype is pumping up the stocks that will supply electricity for all those data centers.

Economy/Market Indicators

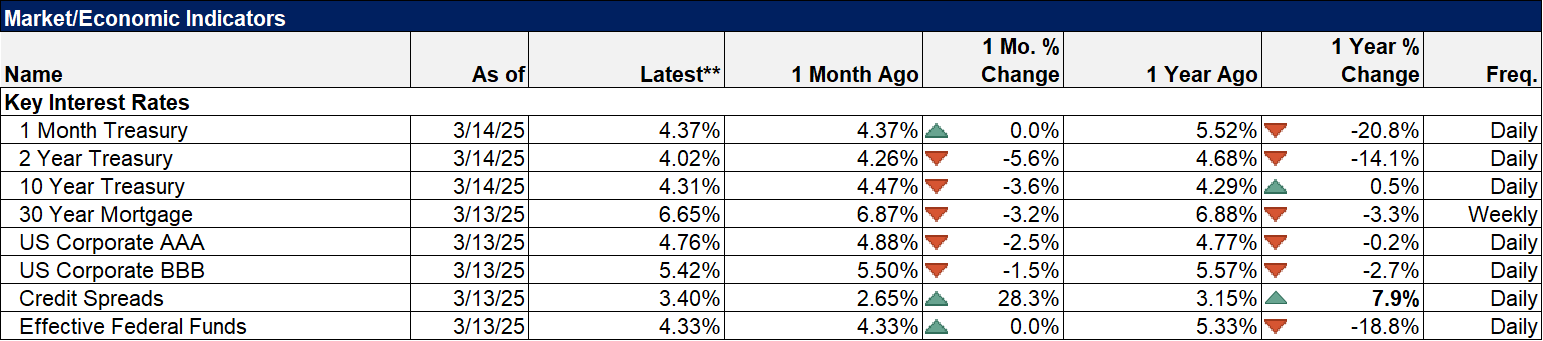

Credit spreads are finally widening off their lows. The increase in the spread so far is about 78 basis points but the current level of 3.4% is not worrisome yet. On the other hand, the move has been fairly rapid; investors are reducing their exposure to risky credits.

On the positive side of things, mortgage rates continue to fall and there was another good rise in mortgage applications last week (+11.2%).

Economy/Economic Data

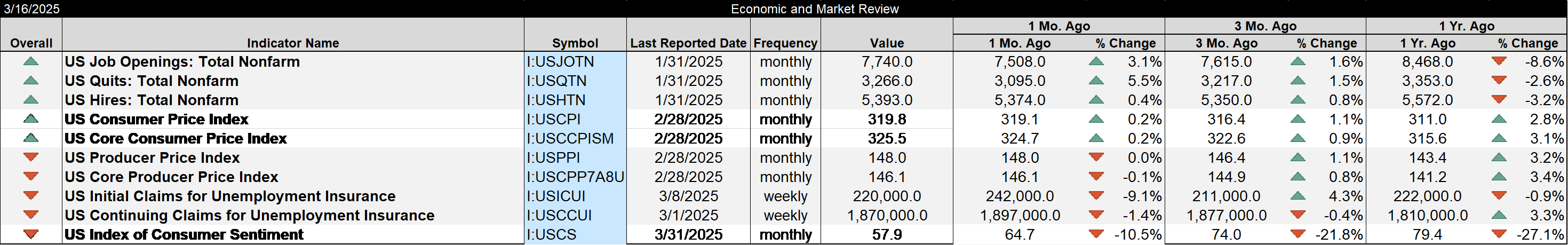

- Job openings rose but are still higher than the pre-COVID peak.

- Quits are still a little less than the pre-COVID peak but were also up last month. Quits are mostly a measure of confidence; people don’t quit their job unless they are pretty darn sure they can get another one.

- CPI and PPI were both less than expected but are also both above the Fed’s target. And the rate of change has slowed considerably. 3% inflation is not a disaster but it may keep the Fed on hold longer.

- Consumer sentiment continues to drop but the current level of 57.9 is about as bad as it gets. There have been only 24 instances* in the history of the survey when the index fell below 60. If you bought the S&P 500 in the month it first fell under 60, you would have been positive 6 months later in 20 of the 24 cases and you’d have been up a year later in all but 3 cases. If you waited to buy until the index rose back above 65, all instances show a positive return a year later with an average gain of 19.4%. That’s the hard part about investing; you have to buy when everyone else is negative.

*November ’74 and February ’75 (the survey was quarterly back then), April to June 1980, May/June of ’08, October/November ’08, February/March of ’09, August/September of ’11 and the longest stretch in 2022 (March, May, June, July, August, September, October and November), May ’23 and now.

Stay In Touch