Sweeping tariffs and a shift away from strong dollar policy can have some of the broadest ramifications of any policies in decades, fundamentally reshaping the global trade and financial systems.

There is a path by which these policies can be implemented without material adverse consequences, but it is narrow, and will require currency offset for tariffs and either gradualism or coordination with allies or the Federal Reserve on the dollar. Potential for unwelcome economic and market volatility is substantial, but there are steps the Administration can take to minimize it.

The Trump Administration is likely to increasingly intertwine trade policy with security policy, viewing the provision of reserve assets and a security umbrella as linked and approaching burden sharing for them together.

– Chair of President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors

A Users Guide To Restructuring The Global Trading System

I – and many others – have written about the uncertainty around future economic policy and how that is affecting markets. There is, however, a blueprint for future economic policy, one written by the Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors, Stephen Miran. It was published right after the election and lays out an ambitious plan to, as Mr. Miran puts it in the title of the paper, restructure the global trading system. It is, as he makes plain repeatedly throughout the essay, a plan with “substantial” risk of “unwelcome economic and market volatility”.

It is also a plan riddled with inconsistencies and contradictory aims. The most obvious problem is that a weaker dollar and “currency offset” for tariffs cannot be accomplished simultaneously because they require opposite moves in the dollar. What is currency offset and why is it important to the administration? When the US imposes tariffs on another country, standard trade theory predicts a rise in the dollar and a fall in the currency of the country being tariffed. There has been a lot made of the fact that tariffs were not inflationary in Trump’s first term and currency offset is the reason. Most of the tariffs in his first term were against China and the dollar did rise against the Yuan after the imposition of tariffs.

The problem is that if you have currency offset, the tariffs don’t accomplish their primary goal of reducing imports. In order for that to happen, the price of the imports must rise to induce consumers to buy fewer imported goods. The fall in the Yuan offset the hoped for price hike and so the trade deficit was not reduced (there’s more to it than that but that was one reason). If you get currency offset, you don’t reduce the trade deficit (which is more a function of our own budget deficit anyway) and if you don’t get currency offset, prices rise. If instead the dollar falls – as it has recently – the price rise is likely to be across domestic and imported goods – what we call inflation. That is what President Trump and his advisors are trying, unsuccessfully so far, to avoid.

Mr. Miran spends a good portion of his essay on the effects of tariffs, not just on the currencies involved, but how their implementation could affect the US and global economy. It is a complicated discussion to say the least but the end result is decidedly underwhelming. The main benefit of imposing tariffs is that it depresses the demand for imports which eventually fall in price as a result.

While the tariff produces distortionary welfare losses due to reduced imports and more expensive home production, up to a point, those losses are dominated by the gains that result from the lower prices of imports. Once import reduction becomes sufficiently large, the benefits from lower prices of imports cease to outweigh the costs, and the tariff reduces welfare.

The main benefit of imposing tariffs, according to this, is that import prices eventually fall, which would seem to make the imposition of the tariffs moot. Another way to reduce the price of imports is what we’ve been doing since the last time we went down this tariff path in the 1930s – remove trade barriers. Furthermore, as Miran admits:

If the U.S. raises a tariff and other nations passively accept it, then it can be welfare-enhancing overall as in the optimal tariff literature. However, retaliatory tariffs impose additional costs on America and run the risk of tit-for-tat escalations in excess of optimal tariffs that lead to a breakdown in global trade. Retaliatory tariffs by other nations can nullify the welfare benefits of tariffs for the U.S.

Thus, preventing retaliation will be of great importance.

It would appear that ship has sailed. The best way to minimize retaliation would be to implement tariffs gradually and quietly, or pretty much the opposite of what has happened so far. To give the administration the benefit of the doubt, it may be that what is going on now is a kind of misdirection. By threatening large tariffs and soon, the administration has reduced growth expectations, the result of which has been a roughly 50 basis point reduction in long-term interest rates. Real interest have fallen about the same and that has reduced the value of the dollar. I suppose it is possible this has been done on purpose, but if so, it directly contradicts the plan laid out by Miran. We’ll find out in April whether this is a bluff or if the full panoply of trade restrictions will be implemented up front. If it is the latter, retaliation will not be theoretical.

The last part of the paper is a long treatise on how to reduce the value of the dollar without appearing to want to reduce the value of the dollar and without affecting its role as the world’s reserve currency. It gives a whole new definition to the word convoluted and would require the rest of the world to accede to our demand to have our cake and eat it too. Even Miran seems to think that unlikely:

As things stand, there is little reason to expect that either Europe or China would agree to a coordinated move to strengthen their currencies.

Another idea considered is to impose a tax on foreign holdings of Treasuries. Another is to force foreign official holders (central banks) to accept a swap to long-term (100 year) zero coupon bonds for their current interest bearing Treasuries. Neither of these is, in my opinion, plausible or in our best interests. If you tax something – in this case foreign ownership of US government debt – you will get less of it, at least at the current price. Miran seems to think this is a benefit because it would reduce the value of the dollar but with $36 trillion in outstanding debt, the US needs all the buyers it can find.

Mr. Miran lays out a plan that envisions making changes to tariffs first and only working on the dollar after reducing the deficit and finding a new Chairman of the Fed who is pliable enough to assist in the plan.

Tariffs will likely precede any shift to soft dollar policy that requires cooperation from trade partners for implementation, since the terms of any agreement will be more beneficial if the United States has more negotiating leverage. Last time, tariffs led to the Phase 1 agreement with China. Next time, maybe they will lead to a broader multilateral currency accord. Therefore, I expect policy to be dollar-positive before it becomes dollar negative.

Well, so far, so bad. Big global economic plans like this have one common flaw. The author can never anticipate all the consequences of their policies. In this case, the idea of sharing the burden of global security more evenly is causing the dollar weakness to come first. Germany and the EU are planning to spend roughly $2 trillion between them on infrastructure and defense and the money has to come from somewhere. Take a wild guess where that is…

That doesn’t mean the burden shouldn’t be shared more evenly but doing so will mean giving up some of the benefits we gain from shouldering most of the load. And yes, there are benefits, the main one being that a strong dollar allows us to enjoy a higher standard of living than our allies. If this weakness continues, if the dollar really gets into a significant downtrend – and that hasn’t happened yet – the rest of the administration’s agenda becomes that much harder to implement.

Joe Calhoun

Environment

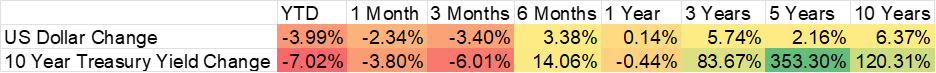

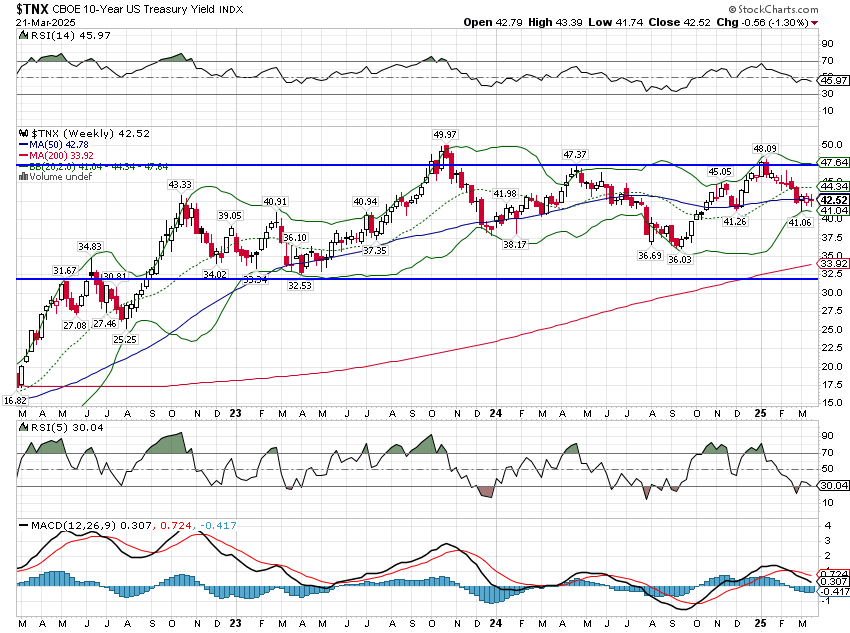

The dollar is down 4% YTD but it is not in what I would call a defined downtrend. One milestone to look for though is very close – a year-over-year decline in the value of the dollar. It would still be hard to call that anything other than a short-term downtrend but it can have psychological implications. It is hard to call the dollar strong when it’s down over the last year and if it isn’t strong then it’s…not strong. I know that sounds like a hedge but that’s because it is. The real call would likely come if the dollar breaks down below the channel it’s been in for the last 36 months. Technical analysis works only because others are using it and you can believe that technicians are watching that 99-100 level like a hawk.

We’re also getting close to another milestone – large speculators are nearing a net short position in the dollar index. If the COT report shows a net short it would be the first time since late 2020. Hedge funds are also close to being net short. The President always gets the dollar he wants and this one wants it weak. So does the chair of his Council of Economic advisors, his Treasury Secretary, and his Vice President. I suspect we’re about to get one of those careful what you wish for moments.

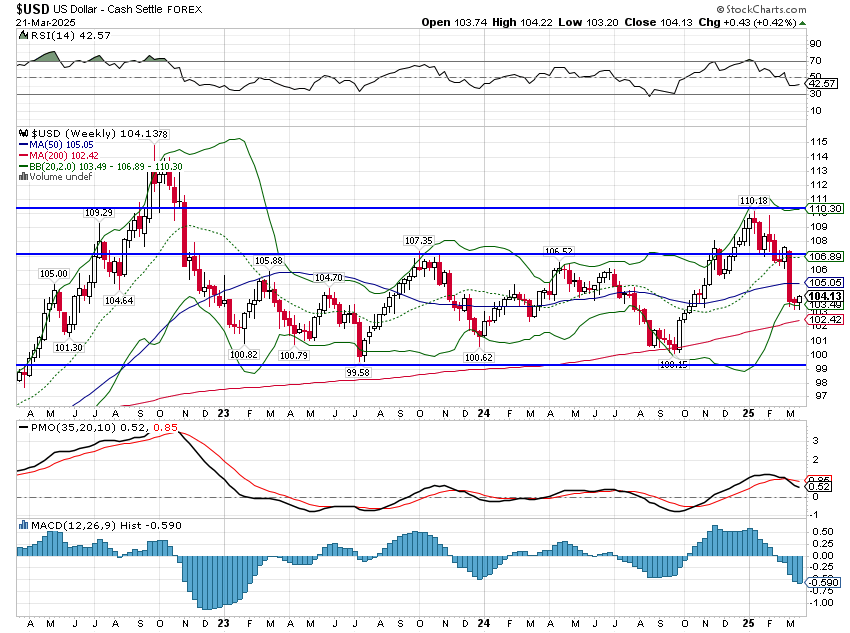

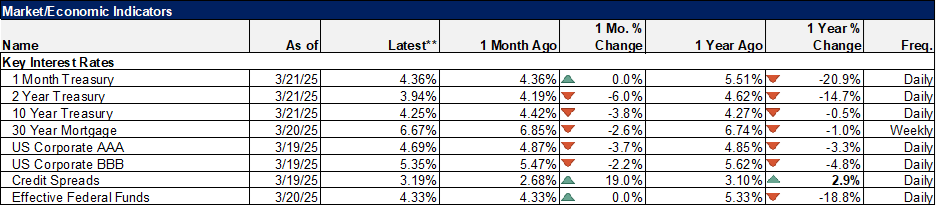

Rates were down last week but, like the dollar, the 10-year Treasury yield is not yet in a downtrend. Unlike the dollar it is already down year-over-year. The bottom of the range is a full 100 basis points below the current market though. The 2-year yield is a lot closer so if Fed policy becomes more dovish – which it didn’t last week – then we could get that bull steepener that happens just before recession. The bottom of the 2-year range is less than 50 basis points lower.

Markets

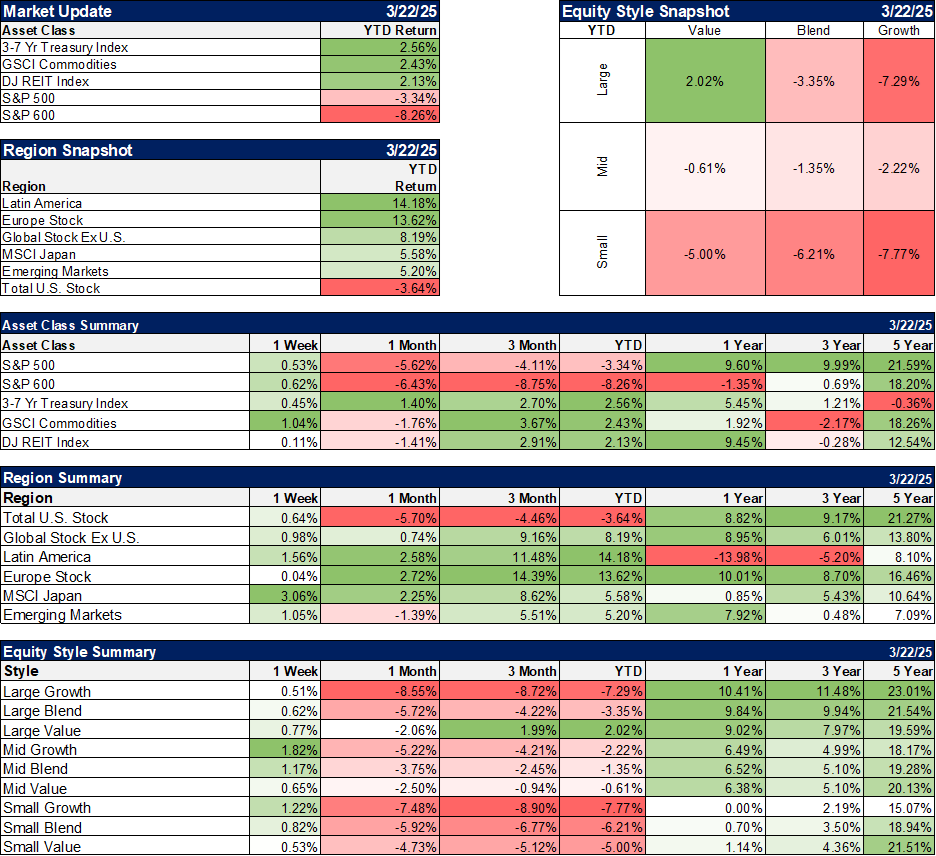

After 4 down weeks in a row, the S&P 500 managed to eke out a gain last week. US stocks of all stripes are oversold right now so a bounce would not be surprising. International stocks are in the opposite position, overbought but not by nearly as much, so a correction there would not surprise either.

YTD, as you can see, value is outperforming but the only size that is actually up is large value. The spread between large value and large growth is pretty extreme for such a short period of time. Nevertheless, growth is still winning over the last year although the spread has narrowed considerably. The 5-year difference has also narrowed a lot and is now less than 4%. Noteworthy, small and mid cap value are outperforming growth over the last 5 years. They are also closing in on large growth in the five-year time frame.

International stocks have been the big winners this year as the dollar has come down. Everyone knows that international has outperformed this year but the surprising thing is the Eurozone stocks have outperformed the S&P 500 over the last 3 years. Interestingly, that period coincides almost exactly with Russian’s invasion of Ukraine. That’s why investors shouldn’t be trying to predict the future. The question now is whether this is the start of a long-term trend or just another short-term trend bound to fail. That will be determined by the dollar. If it really gets in a downtrend, international will almost certainly continue to outperform.

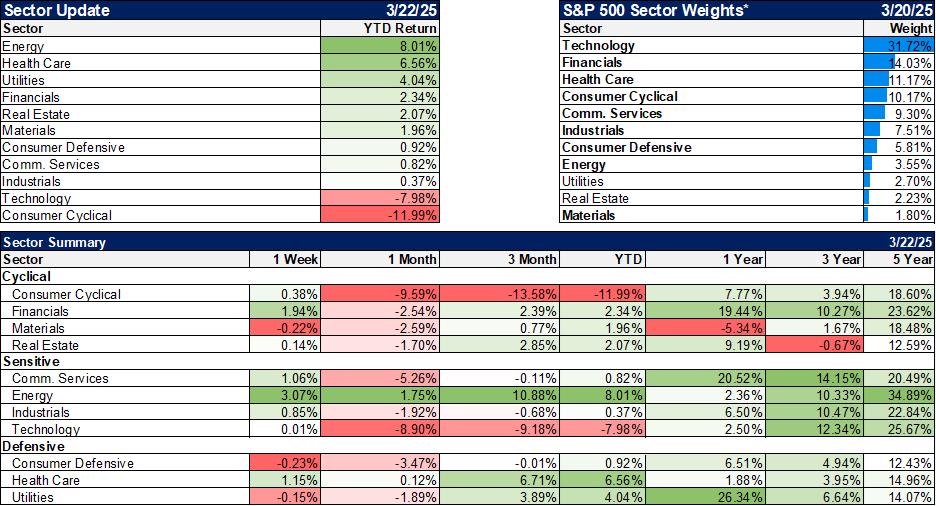

Sectors

Energy and financials led last week and energy is the leading sector for the year. Healthcare is also finally coming off the mat after underperforming badly over the last 3 years.

Economy/Market Indicators

Credit spreads, which have been widening some recently, rallied last week with spreads narrowing by 23 basis points.

Economy/Economic Data

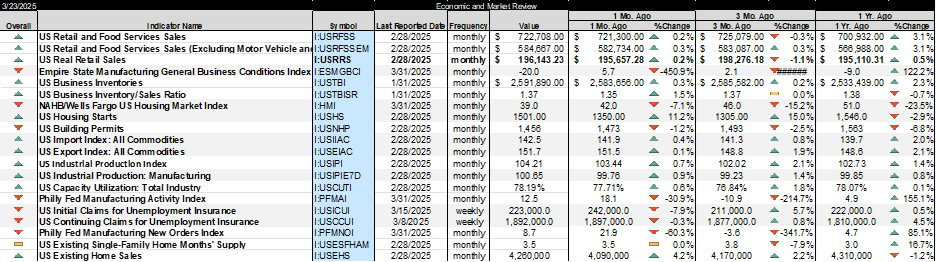

- Retail sales were disappointing, up only 0.2% in February. This is starting to look like a trend.

- The Empire State manufacturing survey turned negative again. New orders fell as inventories grew. That isn’t what we’re looking for.

- Business inventories continue to build as companies front run tariffs.

- Housing starts were a positive surprise, up 11% in February but permits were basically flat and the Housing Market Index fell to 39 (50 indicates expansion).

- Industrial production was up more than expected as motor vehicles and parts manufacturing surged 8.5%. That’s tariff frontrunning as car companies try to stockpile parts before April.

- The Philly Fed manufacturing index fell but stayed positive. New orders and shipments were down.

- Existing home sales were also better than expected, up 4.2%. That’s probably due to falling mortgage rates but inventory also continues to rise.

By the way, the Fed met last week and did nothing. President Trump said they should have cut rates. Get used to that until Jerome Powell gets replaced with someone Trump can brow beat into doing his bidding.

Stay In Touch