The meeting between President Trump and Volodymyr Zelenski last Friday dominated the news over the weekend but for investors the more important news came before that historic (or not) diplomatic faux pas (whose faux pas?). I am not an expert on the nuances of diplomacy (except to say there didn’t appear to be much of it going on in that meeting) and I don’t have any idea how last week’s rupture of Ukraine/US relations will impact the war or the economy of Europe. I have some opinions but you know what they say about those and I won’t inflict mine on you, dear reader. Geopolitics can – and does – impact economies and markets but you don’t have to become an expert on the subject to invest around the changes. The effects will be expressed in markets, primarily through interest rates and exchange rates. That should guide your investments, not your emotional or political reaction.

The more important news, in my opinion, is that President Trump spent most of last week talking about tariffs. Early in the week, he reiterated that Canada and Mexico will get popped with the previously promised 25% tariffs this week while China is going to get an extra 10% on top of what has already been imposed in this first six weeks (that’s all???) of the new Trump administration. Later in the week, he also announced that the administration would soon announce 25% tariffs on the EU because he claimed the bloc was formed to “screw the United States”. This habit of announcing that there will be an announcement soon, seems to be this administration’s version of the Fed’s forward guidance, a way of preparing the market for the actual event. If you’ve been reading these commentaries for any length of time, you know I detest the Fed’s communication policy. Its effectiveness is dependent on the Fed’s ability to predict the future economy which they’ve proven unusually inept at doing. In the case of tariffs, it might not be a bad idea to test the market before actually imposing the tax, but it loses its effectiveness if it always turns out to be a false alarm. The boy can cry tariffs only so many times before the market starts to just ignore him. And that seems to be where we are now.

There is no doubt that the market doesn’t like tariffs; stocks sell off every time Trump announces a new round, but so far, the effect hasn’t lingered. That may not be the case if he really follows through with the Mexico and Canada levies next week. Since he hasn’t actually imposed any tariffs other than those on China, the market seems to have come to the conclusion that he never will. If he really sticks to the deadline this time, the shock may have a bigger and longer term impact. That is assuming that there are no exceptions for particular industries or products and that neither country has done enough to satisfy the President on border and drug smuggling issues. Or maybe the border and fentanyl issues were just excuses for imposing tariffs despite our (mostly) free trade deal with our closest neighbors. They may already be finding a reason to back off the full Monty of Mexico tariffs; did the market rally Friday afternoon because Mexico proposed matching the US tariffs on China?

Mexico agreeing to follow our lead on China is a good example of why it is so hard to get the desired result from tariffs. They seem easy enough; tax the thing you want to import less of and you’ll get less of it imported. But it’s never that simple, ceteris is never paribus. So when the Trump and Biden administrations put tariffs on Chinese goods, the Chinese started routing goods through third countries like Vietnam and Mexico. They also moved some production to those and other areas not affected by the US tariffs. So, despite rising tariffs across two administrations, the US trade deficit continues to grow. I suppose we could reduce our trade deficit by cutting off trade with the entire world but that sounds more like a threat than a plan; autarky isn’t the answer. In the meantime, Mexico offers to close one of the loopholes by aping US tariffs on Chinese goods. Will that work? I suppose that depends on what you mean by “work”. Will it reduce the transshipments of goods via Mexico? Probably. Will it improve our overall trade balance? Not likely. If you want to do that you have to address the root cause and a lack of tariffs isn’t it.

Tariffs are complicated and the more you do, the more complicated they get. A US company that makes something critical to the economy needs an exception to steel tariffs or another one is faced with a choice of raising prices or laying off workers. China and other countries decide to retaliate against US agriculture and subsidies are offered to farmers as a remedy. The only group that truly benefits from tariffs are the politicians who impose them. Is there any doubt that a well-timed campaign contribution would fast track your exemption application? Do you think the granting of exceptions will be based on politics or economics? I know what I believe and it doesn’t matter which party is in the White House or who controls Congress.

If we’re going to impose a high tariff barrier to the US consumer market, the first question we ought to ask and answer is why? The obvious answer is that a large trade deficit reduces US growth but that is an answer with little support in the real world. In fact, the only time we’ve come close to balancing trade over the last several decades is when the US has been in recession. If reducing the trade deficit was the only goal, it could be accomplished pretty easily but I don’t think anyone wants that outcome. So is there a way to reduce the trade deficit that doesn’t involve putting the US economy into a recession? It turns out the answer is yes and we have real world evidence that it works to improve the economy. Ironically, the evidence comes from our neighbor to the north, Canada.

Canada faced a fiscal crisis in the 1990s. Their debt had climbed steadily starting in the 1970s when Pierre Trudeau, Justin’s father, pushed the country to the left, expanding government programs, raising taxes, nationalizing businesses and imposing barriers to foreign investment (similar to trade restrictions). The result was rising government debt and, by the late 80s/early 90s, a trade deficit, in a country reliant on exports. In the late 80s, the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney focused on privatization with great success but he never addressed the budget deficit. General government debt continued to climb until it reached 100% of GDP by the mid-90s. The Canadian dollar was at an all-time low by 1995 and the Loonie was ridiculed by the WSJ as the Peso of the north. Their debt was downgraded twice although they maintained an investment grade credit rating.

Finally, a liberal PM, Jean Chretien, won election in 1993 on an explicit campaign of fiscal reform. His first budget didn’t cut spending much but his second in 1995 finally made some real progress. In two years, they cut spending, exclusive of interest on the existing debt, by 10%. They cut everything from defense to unemployment insurance and reformed the Canada Pension Plan, their version of our Social Security. Federal spending was reduced from 22% of GDP to 17% of GDP by 2000 and 15% by 2006. The country balanced its budget every year from 1998 to 2008. Total government debt was reduced from 100% of GDP to 67% of GDP and federal debt fell to 33% of GDP by 2001.

The result was much improved economic growth. In the 10 years prior to Chretien’s election, GDP grew by 2.3% per year. In the 10-year period after reform started, growth averaged 3.2%. It is also noteworthy, I think, that tax cuts were largely avoided until the early ’00s and then was focused on the corporate rate. The federal rate (provinces tax corporate profits too) was reduced from 38% to 15% and despite that, revenue didn’t decline. Corporate tax revenue has been steady at around 2% of GDP since the 80s. As for trade, the deficit turned to surplus in 1993 and grew to nearly 6% of GDP by 2000. Some of that is probably from the passage of NAFTA but most of it was reduced government deficits and a cheap Canadian dollar. The Loonie hit its all-time low in 2002 and then rose from $0.62 to $1.1 by 2007. The trade surplus fell to a deficit by 2009 as the Canadian dollar rose so that would seem to be the dominant factor. The trade balance stayed in deficit as the country went back to running annual budget deficits throughout the 2010s and government debt is now up 107% of GDP. And, of course, Canada’s economy is now performing poorly again; GDP growth since 2010 was just 2% annually and since 2019 it has averaged just 0.7%.

If the Trump administration were to pursue an aggressive fiscal consolidation plan, it could accomplish everything it wants without resorting to the distortions of tariffs. Shaving 10% off the federal budget (roughly $700 billion) would slow the economy but it would allow the Fed to cut rates and likely reduce the value of the dollar too. That would soften any immediate hit to growth and would also likely reduce inflation, especially in comparison to whatever tariffs would do to prices. On taxes, if the administration wants to reward the working classes that put them in power, they could cut some taxes on the low end of the income scale rather than at the top end. That wouldn’t cost as much and would raise real disposable income where it most needs to rise. Reducing income and wealth inequality need not be an explicit goal but it could be a by-product that pays political dividends. In general though, the reduction in government spending is the important item, not the particular tax package. Leave taxes unchanged and keep cutting until you reach a budget balance like Canada did in 1998. That will reduce the trade deficit that so vexes President Trump and improve the performance of our economy.

The DOGE is supposed to do exactly this of course and I hope they are successful in cutting out waste, fraud, and abuse. And with a budget this large I don’t doubt that there is plenty of it. But it appears to me that DOGE is going beyond that goal and is moving into something that might cause more damage than good. Cutting government spending too fast risks a recession – among other side effects – and if you add in high tariffs, the odds would climb even higher. Tariffs could still be part of the plan to raise revenue but at levels that are not too disruptive to business. Revenue raised from tariffs could be used to “pay” for those tax cuts to the middle/working class. If the Trump administration proceeds with high tariffs and large spending cuts simultaneously, merely to justify a tax cut to upper income earners, the result may be lower tax revenue, continued large budget deficits and no improvement in the trade account. Markets are already warning that the current program isn’t good for growth and it hasn’t even been implemented yet. I hope we change course before we get the hard landing everyone’s been so worried about the last few years.

If the goal is to improve economic performance, we can accomplish that by seriously tackling our fiscal problems. Canada’s fiscal consolidation in the ’90s and ’00s shows that if you reduce the budget deficit, if you reduce government spending, you can improve the trade account, raise growth, and reduce the debt as a percent of GDP. No tariffs required.

Joe Calhoun

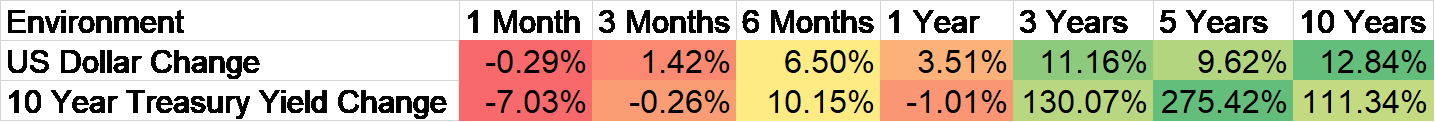

Environment

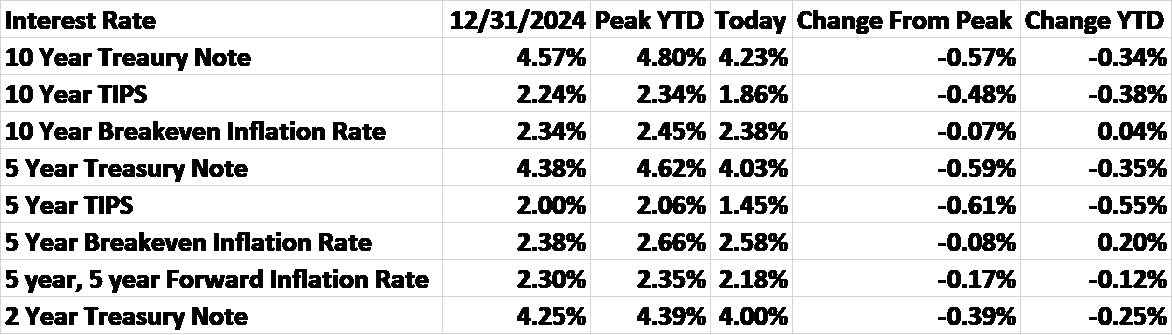

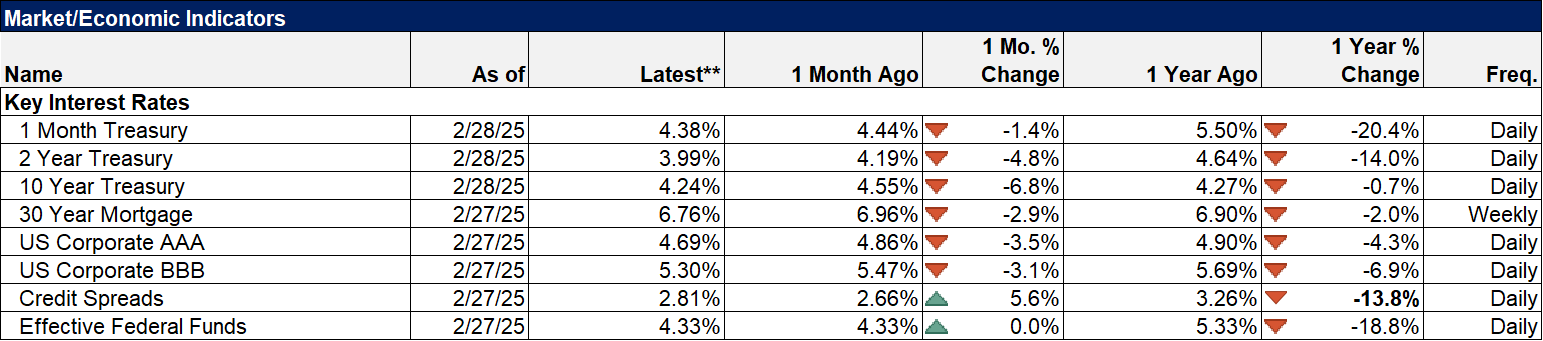

Interest rates fell last week on economic data that was almost uniformly weak (see below). The 10-year Treasury note yield is now down 34 basis points since the beginning of the year and 57 basis points since the peak on 1/13/25. Shorter term yields are also down; the 5-year Treasury yield is down 36 bps and the 2-year is down 25 bps. Here’s a summary of changes in interest rates and inflation expectations YTD:

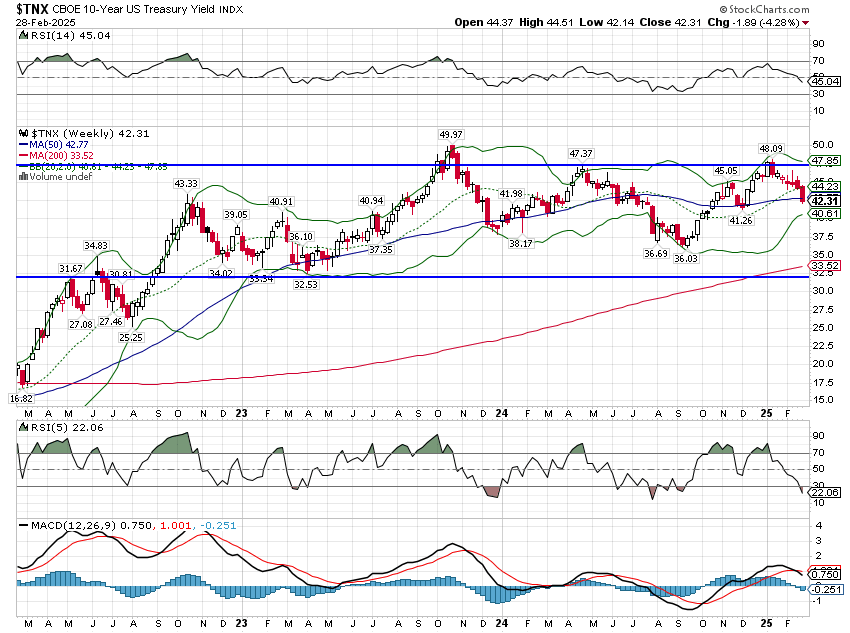

What does this tell us? What is the market saying? The drop in interest rates since the beginning of the year and since the peak in mid-January is mostly a function of lowered real growth expectations. The change in real rates (TIPS) at the 10-year horizon YTD is almost exactly the same as the drop in the nominal bond yield; long term inflation expectations haven’t changed much while real growth expectations have fallen by about a third of a percent, which is pretty significant if compounded for 10 years. At the 5-year horizon, the change in inflation expectations is a little more pronounced at +20 basis points and the hit to growth is larger too. So far, the verdict from the market on the new administrations proposed economic policies is an uptick in short-term inflation but not much change long term coupled with a long-term reduction in real growth. That is consistent with economic theory about tariffs; they change the price level soon after implementation but shouldn’t cause a sustained increase in the rate of change. Tariffs also reduce growth because exports are reduced along with imports due to retaliation.

There is no change in trend for interest rates. In the very short term, rates have fallen but the change is fairly small. Over the last roughly 2 1/2 years, the 10-year rate has traded in a range; right now we are nearing the mid-point of that range. The long-term trend, the secular trend, has reversed after a multi-decade period of falling rates. On a cyclical basis, it seems reasonable to expect somewhat lower rates if tariffs are actually imposed and government spending is reduced significantly. Both of those would tend to reduce NGDP expectations and therefore 10-year rates. Long term though, we believe rates will eventually break out of the top end of the current range due to several factors (demographics mostly).

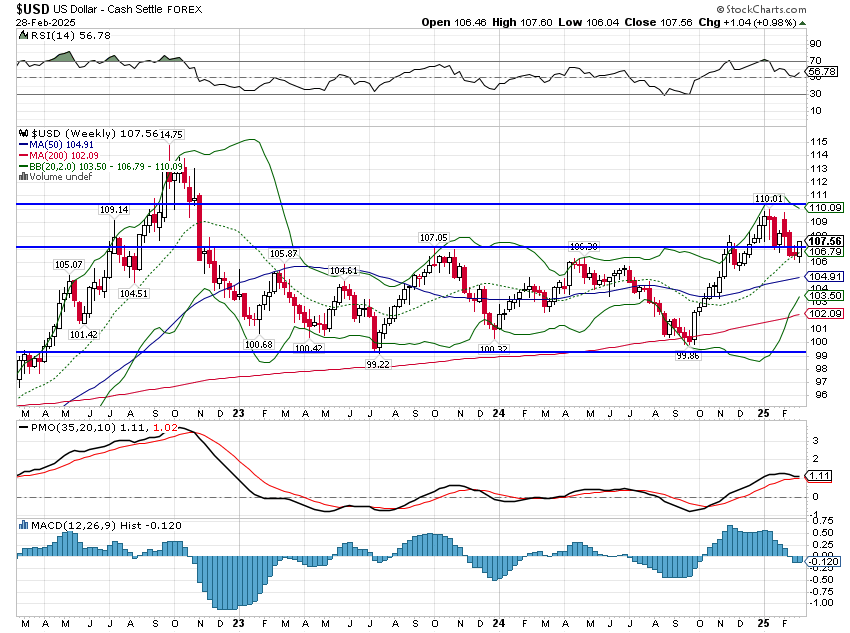

The dollar was up last week due to repeated talk of new tariffs by President Trump. But the gain was insignificant and the dollar is down for the year and since its peak, which came on the same day interest rates peaked. The dollar broke out of its range this year but has pulled back to the previous high of the range. Where it goes from here will depend, to some degree, on what the President actually does with tariffs. The consensus is that the imposition of tariffs will push the dollar higher and that is consistent with economic theory. But economic theory also assumes ceteris paribus, all other things equal, which is most certainly not the case. The Trump administration has explicitly tied foreign policy to trade and economic policy and now so will the market. As the US turns inward, it seems logical to expect other countries and regions to do the same. That, in turn, seems likely to affect capital flows and currency values. Other factors will play a role as well, including our fiscal profligacy. If the Trump administration actually reduced the deficit it could have a positive impact on the dollar. Unfortunately, based on the Republicans’ budget blueprint, that seems quite unlikely.

In the shorter term, I’d also be skeptical of much more upside to the dollar if the market continues to mark down growth expectations. Lower rates – especially lower real rates – are dollar negative.

Markets

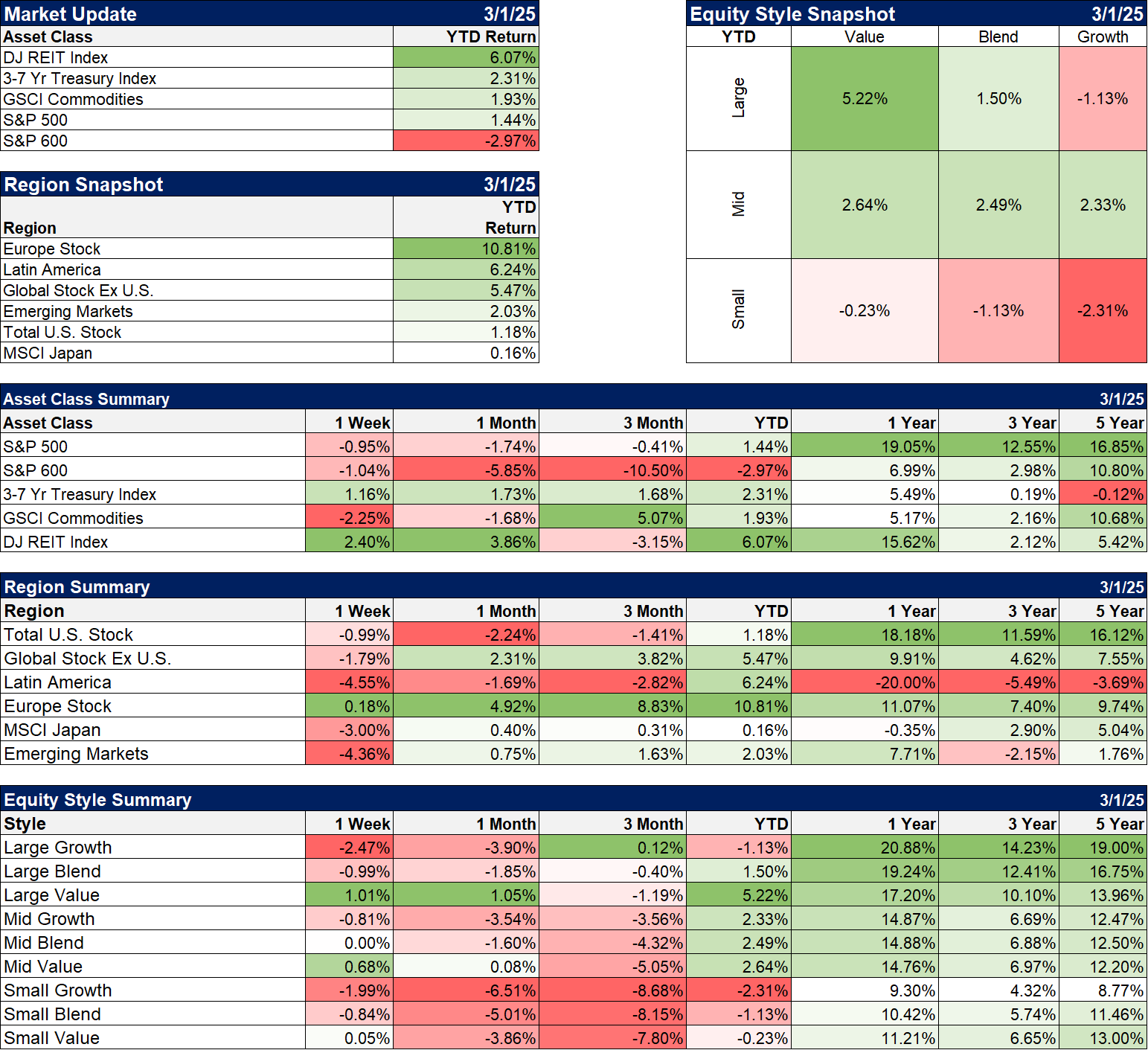

Year-to-date, there are a variety of assets outperforming the S&P 500 and as diversified, multi-asset class investors we are glad to see things broadening out. But it is also very short term and the old trends are mostly still in place. The S&P 500 and gold continue to outpace everything else over the last 1 and 3-year periods. Large value stocks have done pretty well too but growth still maintains a sizable edge over the 3-year period. International stocks are outperforming this year but are lagging by a lot over the last 1, 3, and 5-year periods. It is likely only a matter of time before that reverses and maybe this year is the start, but we’ve seen plenty of false starts before. Small cap stocks continue their role as the most frustrating asset in anyone’s portfolio but lower rates might help that change, at least for the short term.

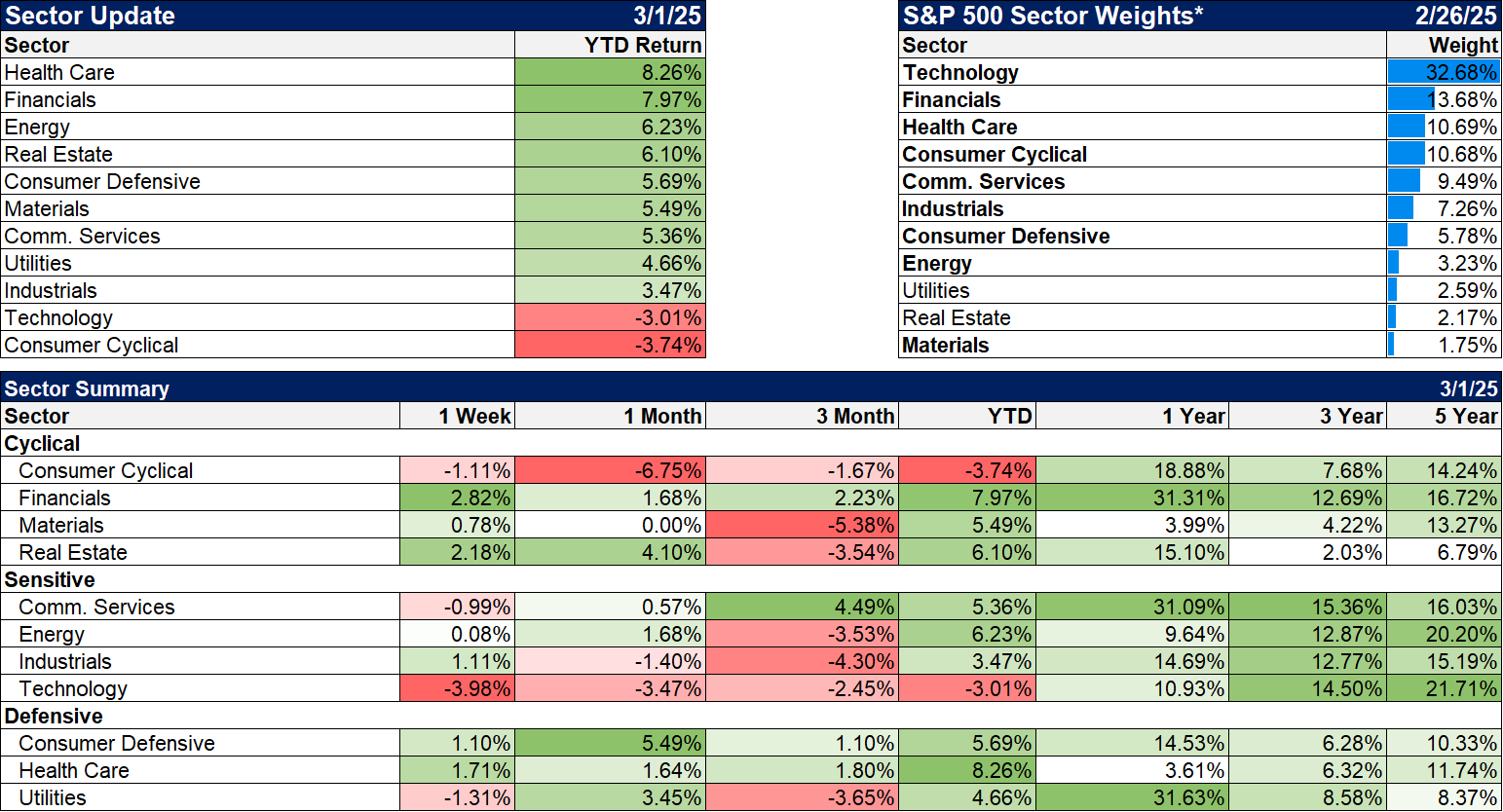

Sectors

For the week it was defensive sectors like real estate, consumer non-discretionary (staples), and health care that did well. Utilities are still trying to price in AI and having a hard time of it. They’ve soared based on the idea that AI means a vast increase in energy consumption. Now they’re pulling back on fears that the need was overblown. Which is it? It is impossible to know but history says AI will induce overinvestment which will lead to a glut and falling prices. In the dot com case it was fiber optic cable. In the AI cycle, it may well be data centers and therefore energy usage. On the other hand, energy usage seems likely to continue to grow as long as the world economy does.

Economy/Market Indicators

No big changes in our market based economic indicators.

Economy/Economic Data

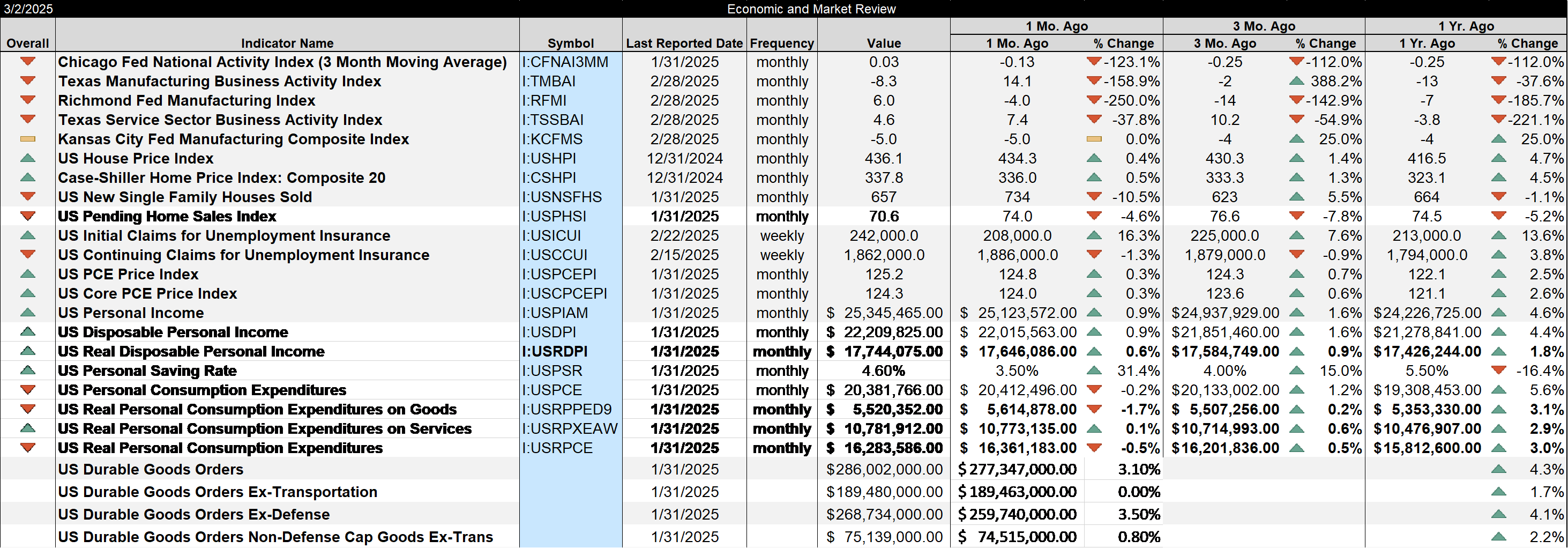

The 3-month average of the CFNAI is 0.03, which means the economy is currently growing right at trend (a reading of zero would be trend). That about sums up the good data from last week. By the way, you can watch this video for a summary and my thoughts on the data.

Most of the rest of the data showed an economy that is slowing. How much of that was already baked in the cake prior to Trump’s election and how much is due to uncertainty around his administration’s future policies is impossible to determine. We know uncertainty is being talked about a lot on company conference calls and we know it is a big part of why Consumer Confidence is back below the “looking for recession” level. We also see it in the regional Fed and small business surveys. But policy uncertainty isn’t all that’s going on right now and hard data is mixed. For instance, we hear companies citing uncertainty in their conference calls but core capital goods orders last month were pretty strong at up 0.8%. On the other hand, over the last year they are only up 2.2% which is below the rate of inflation, so if companies aren’t investing right now that isn’t really much of a change.

But the data is what it is and the markets we watch for clues about the health of the economy agree – the economy is slowing modestly.

Highlights:

- Real disposable personal income (after tax, inflation adjusted) was up 0.6% in January and 1.8% year-over-year

- Real personal consumption of goods fell 1.7% last month, a really terrible number but we don’t know why. It could have been weather related or it could be uncertainty related. Whatever it is, it isn’t good.

- Pending home sales are at the lowest since 2001 (as far back as we have data)

- Durable goods orders ex-transportation were flat.

- Jobless claims rose to 242k, up from 208k a month ago. Most of the rise was from the DC area, a stat that seems like damn good news to me if not for those affected.

- PCE inflation was up 0.3% on the headline and core measures. The year-over-year change is 2.5% and 2.6% respectively. That isn’t far from the Fed’s target but the improvement has stalled. Tariffs will almost certainly move it in the wrong direction, at least in the short term.

Stay In Touch