Jerome Powell’s tenure as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve has ended. Not literally, of course, because apparently Scott Bessent has, for now, talked President Trump out of firing him. But despite that reprieve, there are now several Chairmen of the Federal Reserve, none of them named Powell. He is the lamest of ducks. A lame duck, literally, is a duck that is unable to keep up with the rest of the flock and is, therefore, vulnerable to predators. Jerome Powell has already fallen to his stalkers, whose names include Kevin Warsh, Christopher Waller, and Kevin Hassett. There may be more but these have been deemed by the chattering classes as the most likely to officially succeed Powell. And in a way, they already have.

A lot of modern monetary policy is about communication or forward guidance as it is called by economists and central bankers. Forward guidance – communicating to the market the intent of the central bank – has been used extensively since the 2008 financial crisis, mostly because rates were so low that they couldn’t be lowered any more. In the world of central banking, lower interest rates provide “stimulus” and so not having the ability to lower them constrains their ability to help the economy recover. After 2008, they used forward guidance to tell the market that they wouldn’t be hiking short-term rates for a long time, which they believed would keep long-term rates low and stimulate investment. It didn’t exactly work out that way because the market interpreted that to mean the economy would perform poorly for a long time – why else would the Fed keep rates lower for longer? – and that was, to some degree, a self-fulfilling prophecy. If the monetary authority tells you the economy is going to suck for the next few years, it is understandable that you don’t rush out to make investments in the future. Market speculators, on the other hand, took low rates as an invitation to, well, speculate.

The fatal flaw of forward guidance is that it requires that the Fed be able to accurately forecast the future economy, something they have proven repeatedly they cannot do. When the central bank’s forecast of the future economy is wrong, markets adjust immediately even if the Fed can’t. The Fed does have considerable control over very short-term interest rates, such as the Fed Funds rate (an overnight rate). In the current ample reserves regime, they set the rate on reserves held at the Fed and by doing so, they affect short-term rates throughout the economy. President Trump is mad at Powell because he won’t lower those short-term rates, thinking that if he were to do so, long-term rates – like mortgages – would fall as well. The problem is that Powell can’t lower rates all by himself and even if he could, long-term rates are not set by the Fed, but by the market.

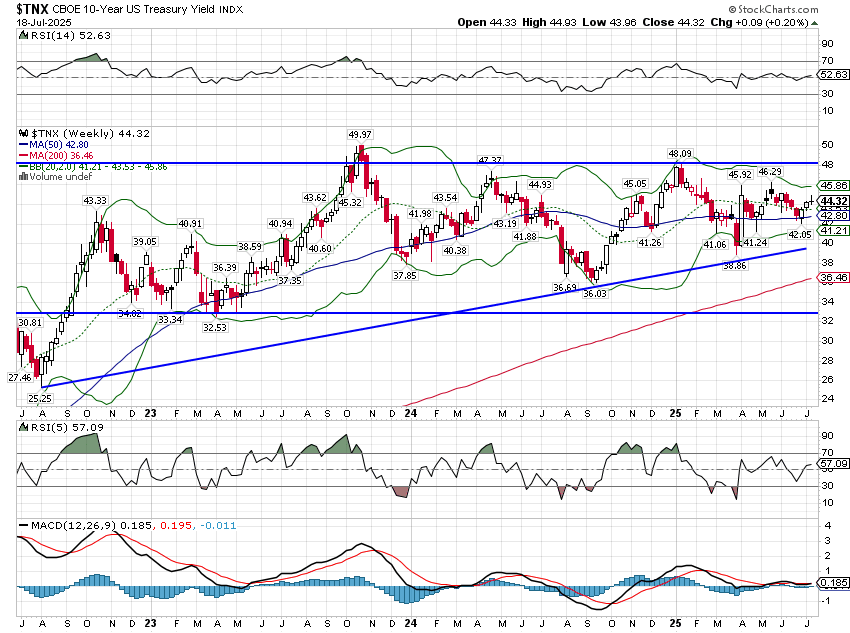

Long-term interest rates – 10-year Treasury rates, for example – are set by the market based on collective expectations about future nominal growth (NGDP). The day before the Fed announced its first rate cut last September 18th, the 10-year Treasury rate hit a low of 3.6%. As soon as the Fed made their announcement, long-term rates started to rise and continued to rise right up to the election in early November, hitting 4.5% on November 15th. After a brief correction, the 10-year rate continued to rise to 4.81% just before the inauguration. More importantly, real rates, as measured by 10-year TIPS yields, also rose, although not as much as the nominal rate. The 10-year TIPS rate rose from 1.53% to 2.34% – 81 basis points – over the same time frame. The market interpretation of the impact of the Fed’s change in policy was that NGDP growth would rise and that most of that gain would be in real growth. Inflation expectations also rose but only about half as much as real growth expectations.

Is that a bad outcome? Far from it. The rise in real growth expectations is exactly what the Fed wanted. They didn’t want the rise in inflation expectations but at least it was a small one. It doesn’t matter what you think about the Fed’s motivation for the cut, the fact is that the result was desirable. Now, the market could be wrong about the impact of the cut; maybe it really sparks more inflation than real growth. Or maybe the change in short-term rates doesn’t really have much impact on the real economy and future growth and inflation will be determined by other factors (which is what I believe). What matters though it not my opinion or yours but the collective opinion of the traders and investors who set the market price. If the market believes the cut will be positive for NGDP growth, long-term rates will rise. And there really isn’t anything the Fed – or the President – can do about it. At least not anything good.

So, think for a minute about what President Trump is saying. He wants the Fed to cut rates because he thinks it would reduce interest costs to the Federal Government. And based on his public statements, as best I can tell, he believes a reduction in interest costs would be positive for economic growth. The problem is that wanting lower interest rates and higher growth are contradictory. He seems to think in linear terms: the Fed cuts rates, the government refinances its debt, growth improves. The problem with that way of thinking is that markets – or more specifically the people that make up markets – aren’t stupid. Markets anticipate, they discount the future immediately, just as they did when the Fed cut in September. Rates didn’t rise after growth improved; they rose in anticipation of it, expectations improved.

Forward guidance has its flaws but communication by government officials, like the Fed Chairman or the Treasury Secretary, do impact markets and therefore the economy. That’s why Jerome Powell is basically irrelevant at this point. Everyone knows that Trump isn’t going to reappoint him as chairman. If the President actually names a successor soon, the market will ignore Powell completely and start listening to the new guy. If he waits to name a successor, it could be a little messy because the market will have to take into account multiple candidates’ views and weight them based on the odds each will get the job. As long as the new chairman sticks to pretty conventional policy, it doesn’t matter much who gets to sit at the head of the FOMC conference table. They can cut short-term rates if they want but if the market interprets that as a future rise in NGDP, long-term rates will rise. If the market interprets the cut as more inflation than real growth, rates would probably rise even more because killing inflation has proven difficult in the past.

I won’t say that the new Fed chair doesn’t matter at all because modern central bankers have a lot of levers to pull and I don’t think they even know what all of them do. Kevin Warsh has recently mused about a new Fed/Treasury accord, coordination between the Fed chair and the Treasury Secretary. His call for a new accord is historically ignorant and, in my opinion, a bad idea. The original Fed/Treasury accord in 1951 ended the Fed’s subservient role to the Treasury and for good reason. During and just after WWII, the Fed controlled interest rates across the entire yield curve to keep war financing costs low. Not allowing long-term rates to adjust to the economic environment may have been politically expedient but it didn’t do any favors for consumers; prices rose 46% from the end of the war to the accord. After the accord, the year-over-year change in prices for the next 10 years averaged just 1.4%. Mr. Warsh apparently wants to go back to the pre-1951 accord way of doing business. I don’t know all the implications of that – and neither does Warsh by the way – but I am pretty certain the market will not like the idea.

In general, the Fed is a lot less important than most people think and they don’t have the magic powers to control interest rates that President Trump imagines. Mostly the Fed has historically just followed the market, cutting or raising rates after the market has already done so. But communication and perception matter too and a more activist, more political Fed will not be welcomed by the market. Treasury Secretary Bessent, more than most, should understand the importance of the market’s reaction to changes in economic policy. He worked for George Soros, whose theory of reflexivity posits that markets don’t just reflect the underlying economy but actually shape its future performance. If the President’s choice of a future chair spooks the market into raising interest rates today, it will impact the economy before his choice ever arrives at the Fed’s newly renovated headquarters.

Environment

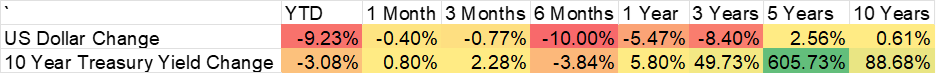

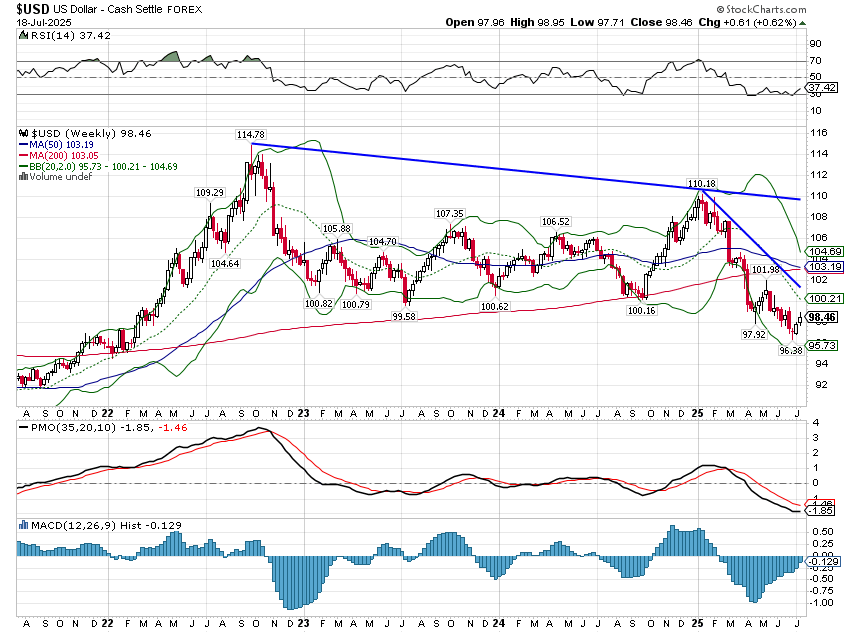

The dollar rally I’ve been looking for appears to have started. Technicals indicate a move to the 101-102 area makes sense. It is interesting that the negative sentiment (short dollar was mentioned as one of the most crowded trades in BofA’s recent sentiment survey) isn’t really seen in the futures markets; it is largely anecdotal. Dollar index positioning is largely flat with only a small net short position among large speculators. Pound sterling, despite a pretty good rally, has only a small net long. The Canadian $, even after a good rally, still has a net short position while large specs are more short the Aussie but not at an extreme. Specs aren’t big believers in the Euro rally either with only a modest net long. That leads me to believe that any rally is likely to be modest and I do expect the dollar decline to continue afterward.

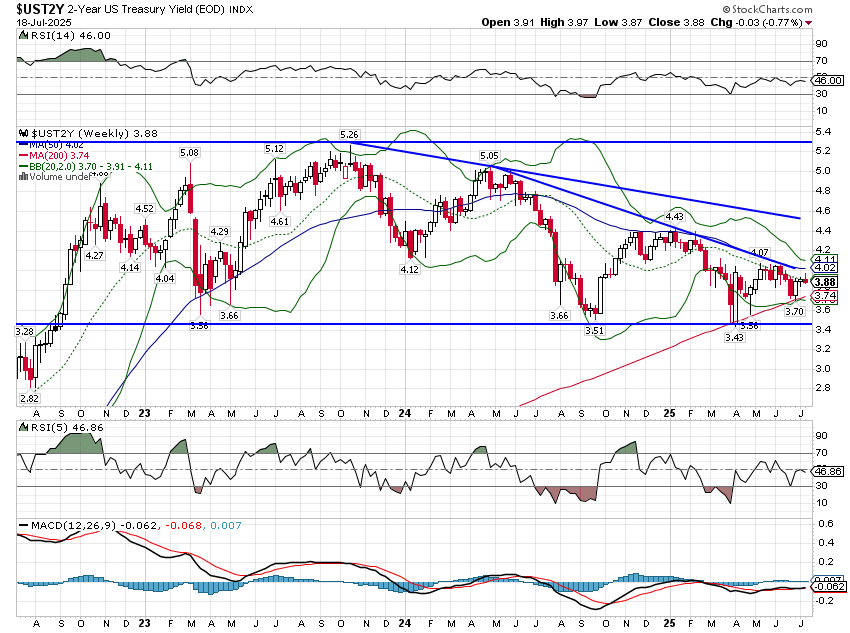

The bear steepener continues in the rates complex with short rates down a bit last week and long end rates up a bit. That is a mild stagflation signal but it isn’t large enough to mean much yet. As I’ve seen saying for some time, there isn’t much change in the growth and inflation outlook since the election. Despite all the angst about tariffs and the browbeating of the Fed and threats to replace the chairman with someone more pliable, markets are not expecting much fallout. That doesn’t mean things are wonderful though. With the 10-year nominal Treasury yield at 4.4% and the 10-year TIPS yield at about 2% that translates to long term expectations of 2% real growth and 2.4% inflation. That isn’t significantly different than the pre-COVID trend and a long way from Treasury Secretary Bessent’s 3% goal. Achieving that goal is also inconsistent with his desire for lower long-term rates. If he wants 3% real growth and 2% inflation, that is consistent with a 10-year at around 5%, not lower. I suppose you could get 3% real growth and 1% inflation but when was the last time that happened other than for a quarter or two? There are only two periods where we were able to get 3% or better growth, inflation less than 3% and a 10-year yield less than 5%. The first was from 1962 to 1966 when real GDP growth averaged 6%, inflation averaged 1.4% and the 10-year yield averaged 4.2%. The other was from about 2003 to 2006 when real GDP growth averaged 3.4%, inflation 2.6% and the 10-year yield 4.4%. Achieving Bessent’s growth goal with reasonable inflation and rates lower than today is going to be very, very hard.

Markets

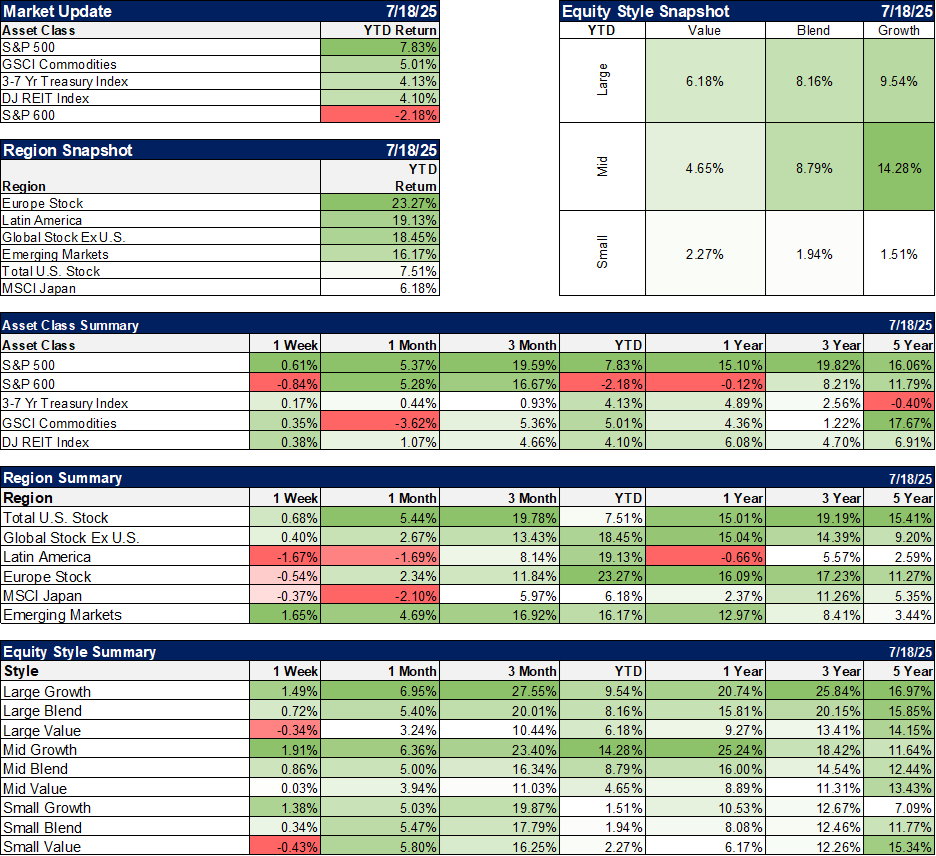

US stocks, bonds, commodities, and REITs were all higher last week by fractional amounts while non-US stocks were mostly down, EM the notable exception. Growth stocks led value as energy stocks had a pretty bad week on the value side and tech did well on the growth side. Growth is outperforming again this year but the 5-year returns still favor value in mid and small caps while large cap growth has a slight lead.

YTD still has international well ahead of US but over the last year, returns are similar. With the dollar starting to rally I would expect the YTD gap to narrow and US to resume the lead over the last year. That contest is really about the dollar so whether international continues to outperform will be mostly about the buck.

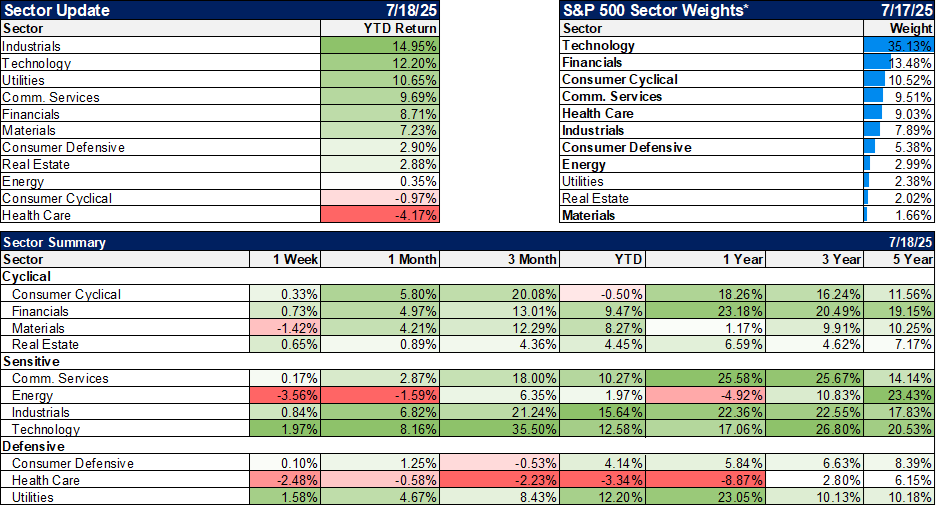

Sectors

The sectors that have lagged over the last year took a hit last week that looks a bit like capitulation, that investors just gave up and when with the momentum. That’s usually not a bad choice but, if true, it means that those lagging sectors may be ripe for reversals. All it takes is some good news, any small item of positivity, to get the ball rolling again. Materials, energy, health care, and real estate need to be on your watch list.

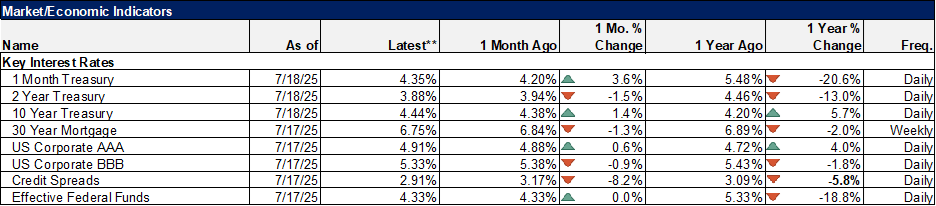

Economy/Market Indicators

Nothing to really report here. Credit spreads are still very tight, meaning that buying corporates over Treasuries is probably not worth the effort. Mortgage rates continue to slowly drift lower but aren’t low enough yet to spark a real estate revival.

Economy/Economic Data

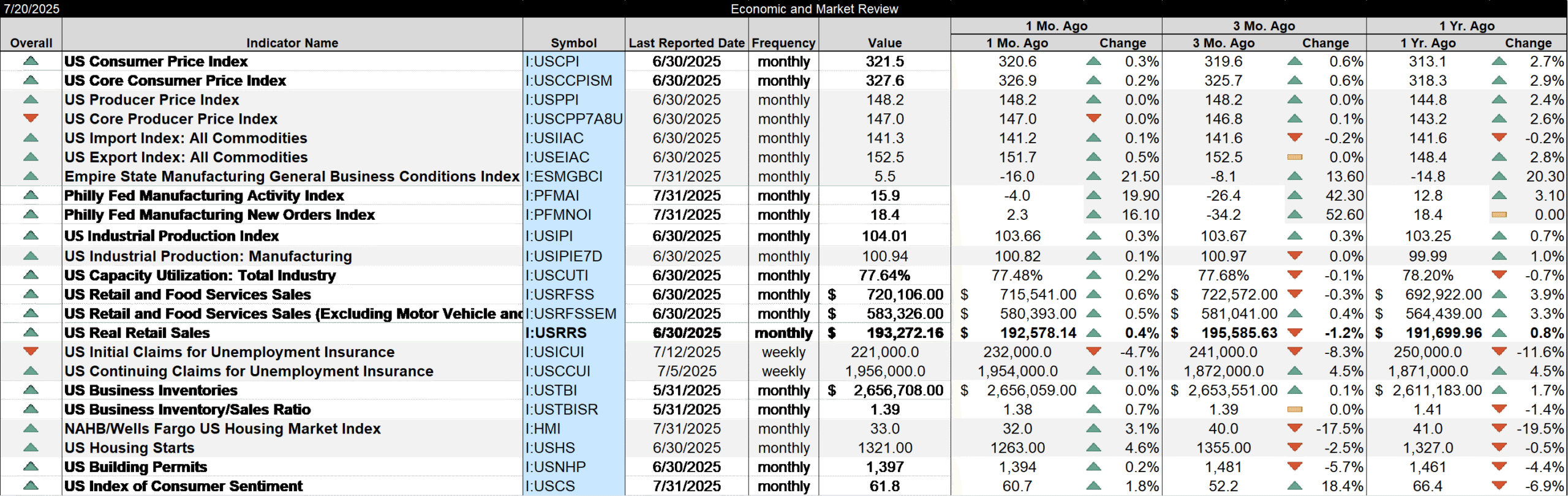

The focus last week was on the inflation data which really wasn’t all that interesting and no, it didn’t prove that tariffs don’t raise prices so ignore everyone saying that. I’ve said before that tariffs, in and of themselves, aren’t inflationary because inflation is a monetary phenomenon. But tariffs will raise some prices relative to others and they can lead to inflation. Monetary policy has some influence over money supply (not as much as you might think but considerable) but it doesn’t have much, if any, control over the demand for money. Money demand is about all the other economic policies that aren’t monetary, including tariffs. If tariffs lead to a lower demand for money – which you’d likely see expressed as lower real interest rates – and monetary policy doesn’t reduce the supply of money to match, then tariffs will affect the value of the dollar. And that, my friends, is essentially what inflation is, a reduction in the value of money. But we aren’t there yet because tariff policy has been on again, off again AND companies prepared for tariffs by stocking up before they hit. We’ll see where this goes in coming months.

The most interesting data of the week though was not about inflation but manufacturing. The two regional Fed surveys released last week, The Empire State survey and the Philly Fed survey, were both very positive. The Philly Fed jumped from -4 to +15.9 while new orders rose from 2.3 to 18.4, both very positive results. The Empire state survey rose from-16 to +5.5 and new orders rose from -14.2 to +2. This report wasn’t as positive as the Philly version but it certainly moved in the right direction. One month doesn’t make a trend so we need to wait to see if this is confirmed but for now it is good news against a more generally, slightly negative trend.

Building permits and housing starts were also better than expected in June but are still very low. With builder sentiment very low and no one positive on housing, contrarians might want to take note.

Stay In Touch