We got the latest report on economic growth last week and it surprised most everyone. Real GDP expanded by an annualized 3.3% in the fourth quarter, well above the consensus estimate of 2%.

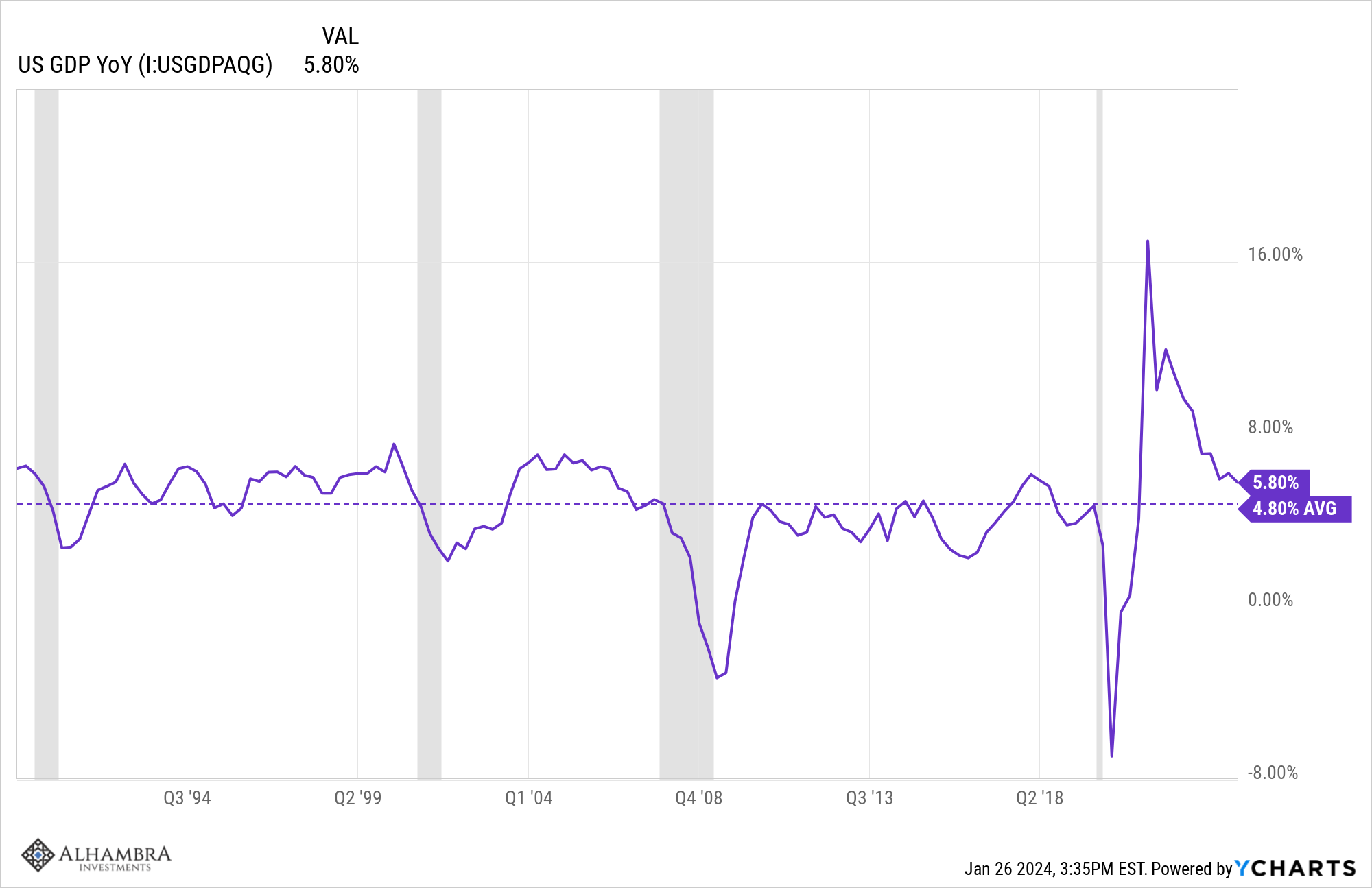

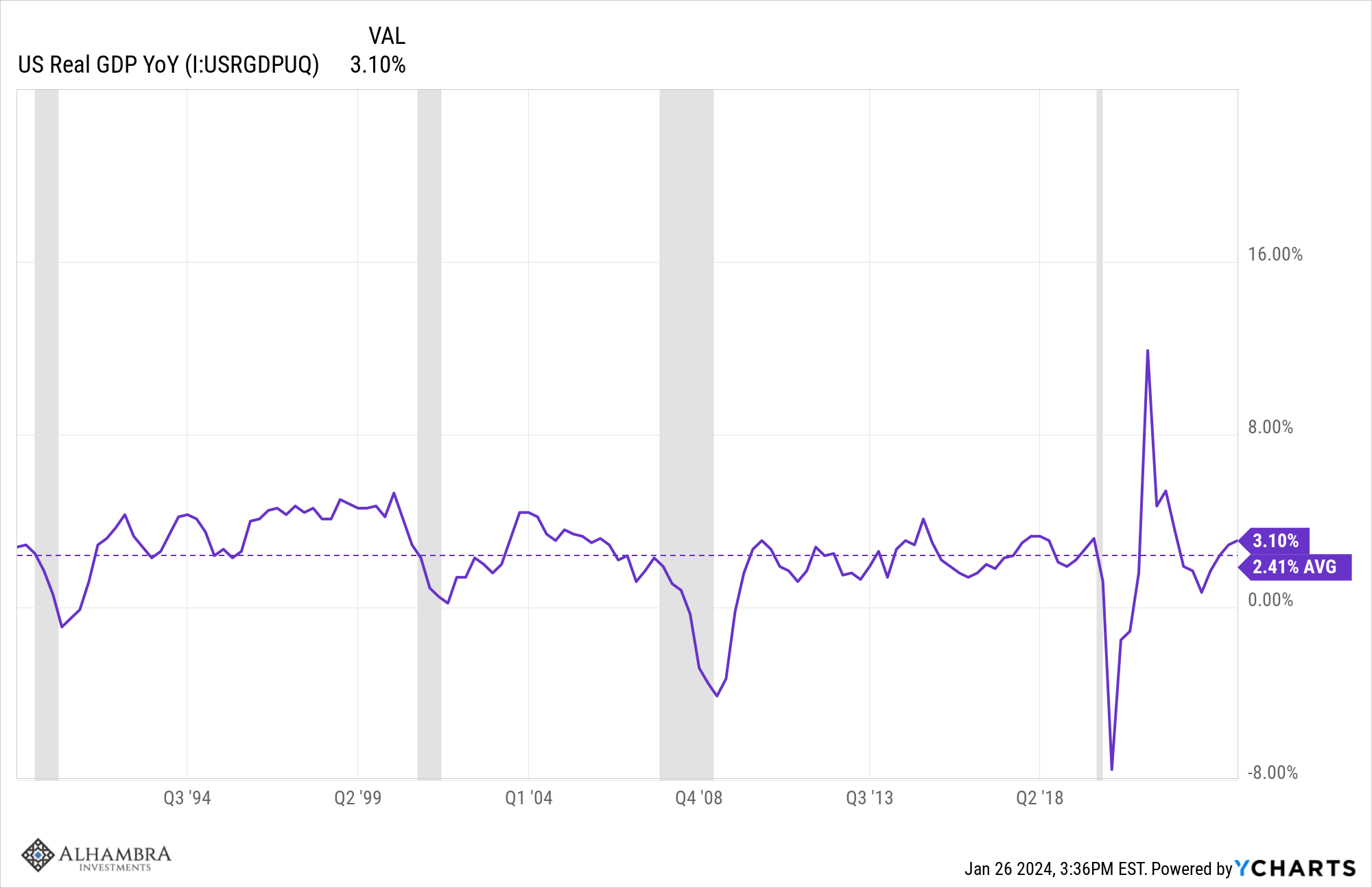

- Nominal GDP expanded an annualized 4.8% quarter to quarter and 5.8% year-over-year. The annualized quarter-to-quarter change is exactly the average annual change since 1990. Real GDP grew by 3.3% quarter to quarter and 3.1% year over year. That is slightly above the average since 1990 of 2.4%.

- Inflation fell. The price index for domestic purchases rose 1.9% versus 2.9% last quarter. The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index rose 1.7% versus 2.6% last quarter. Core prices, excluding food and energy, rose 2%.

- Real disposable personal income (after tax, after inflation) rose 2.5% versus 0.3% last quarter

- Consumption rose 2.8% while investment rose 2.1%. Residential investment added to GDP for the second straight quarter.

- Exports rose 6.3% while imports rose 1.9%

- Government consumption and investment rose 3.3%. Federal was up 2.5% while state and local rose 3.7%

- The breakdown of the 3.3% growth: Consumption 1.91%, Private Investment 0.38% (and only 0.07% was due to inventory), net exports 0.43%, Government 0.56%

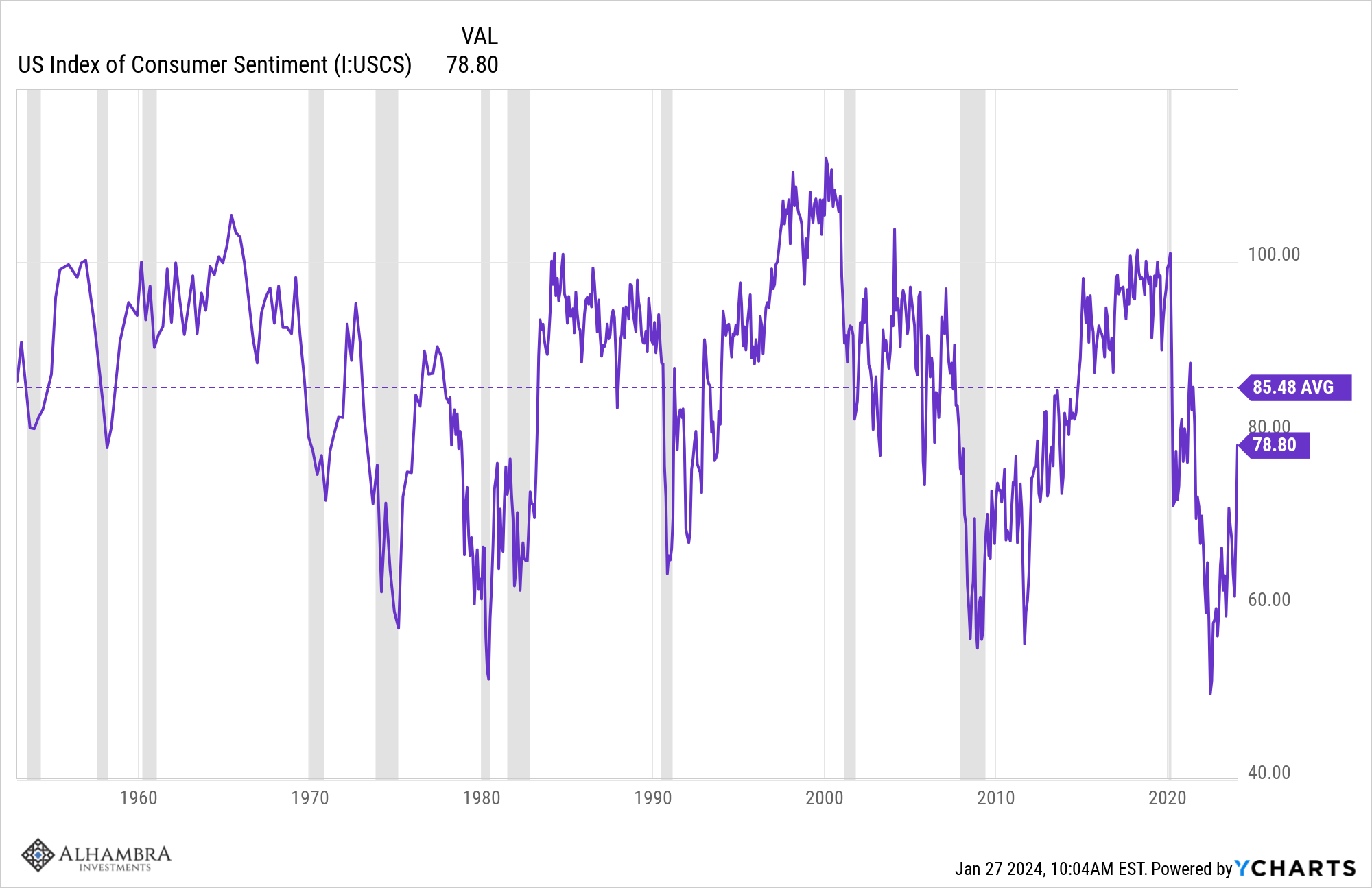

That is a solid report on the state of the US economy. It isn’t perfect and never is but the improvement in the economy over the last year was substantial, especially in light of the negative consumer sentiment and widespread expectations for recession. Consumer sentiment has recently improved – likely a result of a better stock market – to 78.8, up from 63.8 in November and way above the all-time low of 50 set in June of 2022. It is still below the long-term average but what’s more interesting – to me at least – is that it is acting as it normally does coming out of recession. Is the manufacturing recession coming to an end?

Maybe. Manufacturing has been a drag because inventories became bloated after supply chains eased up and delayed goods were delivered. But after over a year of working on inventories, it appears that a restocking cycle may be upon us. We haven’t seen much improvement in the regional Fed surveys yet but the S&P Global Manufacturing PMI improved at the mid-month read to 50.3, a significant improvement from last month’s 47.9 and well above consensus expectations of further deterioration.

New durable goods orders were reported last week and while the headline was flat, the reading ex-transportation was up 0.6%, much better than the expected +0.2%. Transportation orders were down because of Boeing, which isn’t surprising in light of recent events. I won’t say that doesn’t matter because it does, but the rest of the report was surprisingly strong. The ex-defense reading was +0.5% and core capital goods orders were up 0.3%. Personal income and spending, reported on Friday were also solid, up 0.3% and 0.7% respectively.

It is important to remember that all these reports are about the past and don’t say a lot about the future. It could be that the holiday season was a last hurrah before consumers hunker down, but with real incomes still rising, that seems unlikely. Americans are not known for their frugality (although I’m encouraged to see that as a new trend among young people) and if they have the means, they are generally willing to spend. Unfortunately, consumer spending isn’t a leading indicator, usually not falling until after the recession starts. Durable goods orders aren’t any more useful as an advance warning with plenty of monthly and quarterly declines in the past that weren’t associated with recession.

The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Indicators, which have proven very useful in the past in identifying oncoming recessions, are currently at levels associated with recession – and have been for over a year – but of course, it hasn’t happened. That isn’t surprising since the LEI is manufacturing centric which has certainly been in a slowdown. If you look at the individual indicators that make up the total index, the most negative over the last six months are survey-based:

- The inverted yield curve – currently improving (steepening)

- Consumer expectations for Business Conditions – bottomed in mid-2022 and “unexpectedly” rose last month to 85.6 from 77.4 in November

- The ISM index of new orders – bottomed a year ago in January of 2023 at 42.5 and is now rising at 47.1, something you usually see coming out of recession

The most positive are about actual activity:

- Building permits – positive over the last six months

- Core capital goods orders – positive, see above

- New orders for consumer goods – +1.2% over the last six months

- Weekly unemployment claims – near lows last seen in the late 1960s

The US economy is a big, diverse beast and I don’t think anyone can predict the quarter-to-quarter or even year-to-year changes. That doesn’t stop thousands of pundits from trying though and they usually get it wrong. You could probably place pretty high in the guru rankings by just assuming that if things are bad they are going to get better, that the economy will return to its long-term averages. Since 2008, it has been popular – and profitable for some people – to bash the US as past its prime, a has-been nation that doesn’t “make anything anymore”. But we always seem to find the next big thing and continue to invest, consume and grow, to the envy of much of the world.

It is true that the US no longer commands the largest share of global manufacturing as it did for many years after WWII. China now holds that title at around 28% of total global manufacturing output. The US is however, second at around 16%, with only a quarter of the population of China. We’re a lot more productive, which is what matters for economic growth; have you seen China’s economy lately? The US share of global manufacturing is greater than Japan, Germany, and South Korea combined. We may not make many consumer goods anymore but we are still a manufacturing powerhouse.

We are also an energy powerhouse. The US set a record for oil production last year. Not a record for the US but a record for any country. US production hit 13.2 million barrels per day in September. We are the largest producer in the world by a pretty good margin:

US – 13 million bpd

Saudi Arabia – 9 million bpd

Russia – 9 million bpd (est)

Canada – 4.9 million bpd

Iraq – 4.3 million bpd

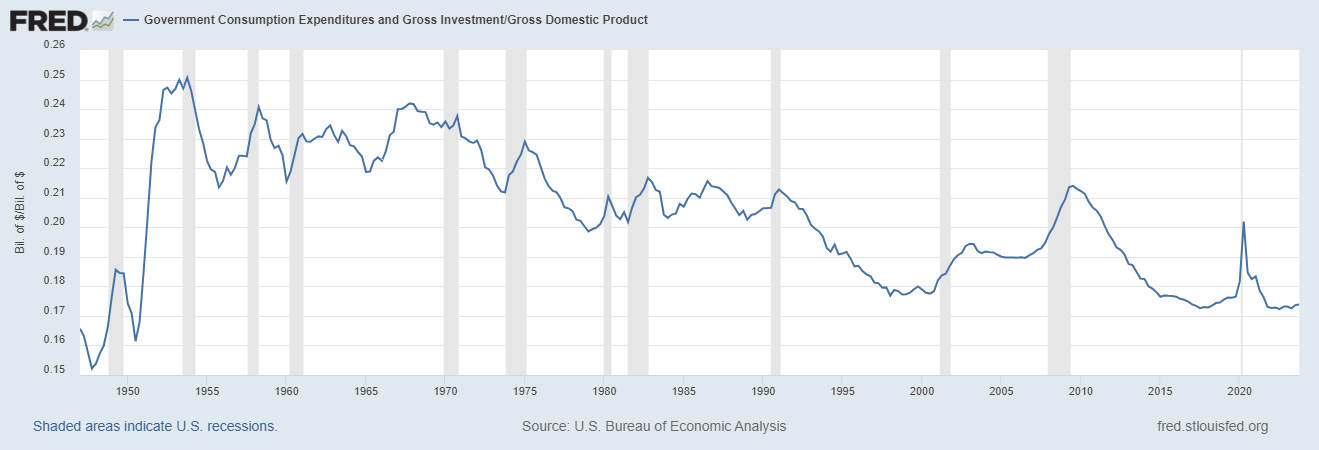

I don’t mean to imply that the US economy is without its problems. There are serious questions about the future of our economy that will have to be answered at some point. Is this expansion driven by government spending and if so, is it sustainable? Well, it isn’t from direct government spending which, at around 17% of GDP is very low:

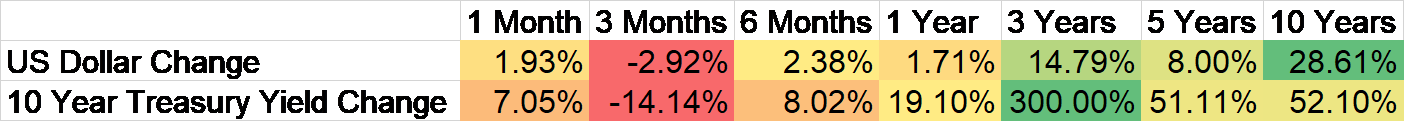

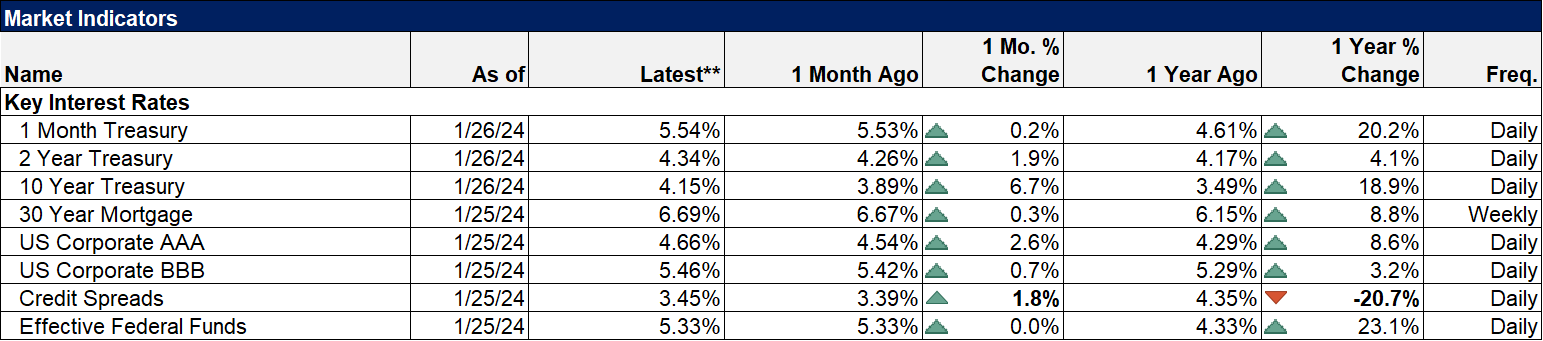

The problem is more with deficits and debt which certainly seem to be out of control and unsustainable. How long before the world of bond buyers balks and forces us to address our fiscal situation? I don’t know the answer to that but a rapid adjustment forced by the market would probably not be pleasant. With so much of our federal spending non-discretionary, any fix is not going to be easy and will likely involve breaking a lot of past promises. For now, though, the market is absorbing the new debt issuance with demand concentrated in the front end of the curve; everyone wants to buy T-Bills these days. I heard a lot of people say that Yellen issued a lot of T-bills in the last quarterly refunding to somehow affect liquidity but I think she issued them because that’s where the demand is. The last thing she wants is to attempt to sell longer-term debt and have the market refuse to buy it. Recent auctions of longer-term debt have not gone all that well and she knows that. There will be another quarterly refunding announcement this week and I expect a lot of T-bill issuance again.

With the economy doing well, the first Fed meeting of the year next week should prove boring. I see no justification in the current data whatsoever that would justify a cut in rates and with inflation continuing to fall, no reason to raise them either. And that assumes that moving short-term rates around has the impact on inflation everyone, including the Fed, thinks. There is now a robust debate among economists about whether the Fed’s rate hikes had anything to do with bringing down the inflation rate, something I brought up months ago. The evidence is thin, to say the least. That doesn’t mean I think they should have left rates at zero because I don’t. There are a lot of reasons interest rates needed to be higher and I think part of the reason the economy is functioning better now is because of it. It has certainly helped the frugal among us, the savers who have had no place to park safe money for over a decade. The annual rate of personal interest income is up 22% since September 2020, an annual raise of about $338 billion. Higher rates may not be good for a government deep in debt or first-time home buyers with 3,000-square-foot houses in their dreams, but it is darn good for the rest of us.

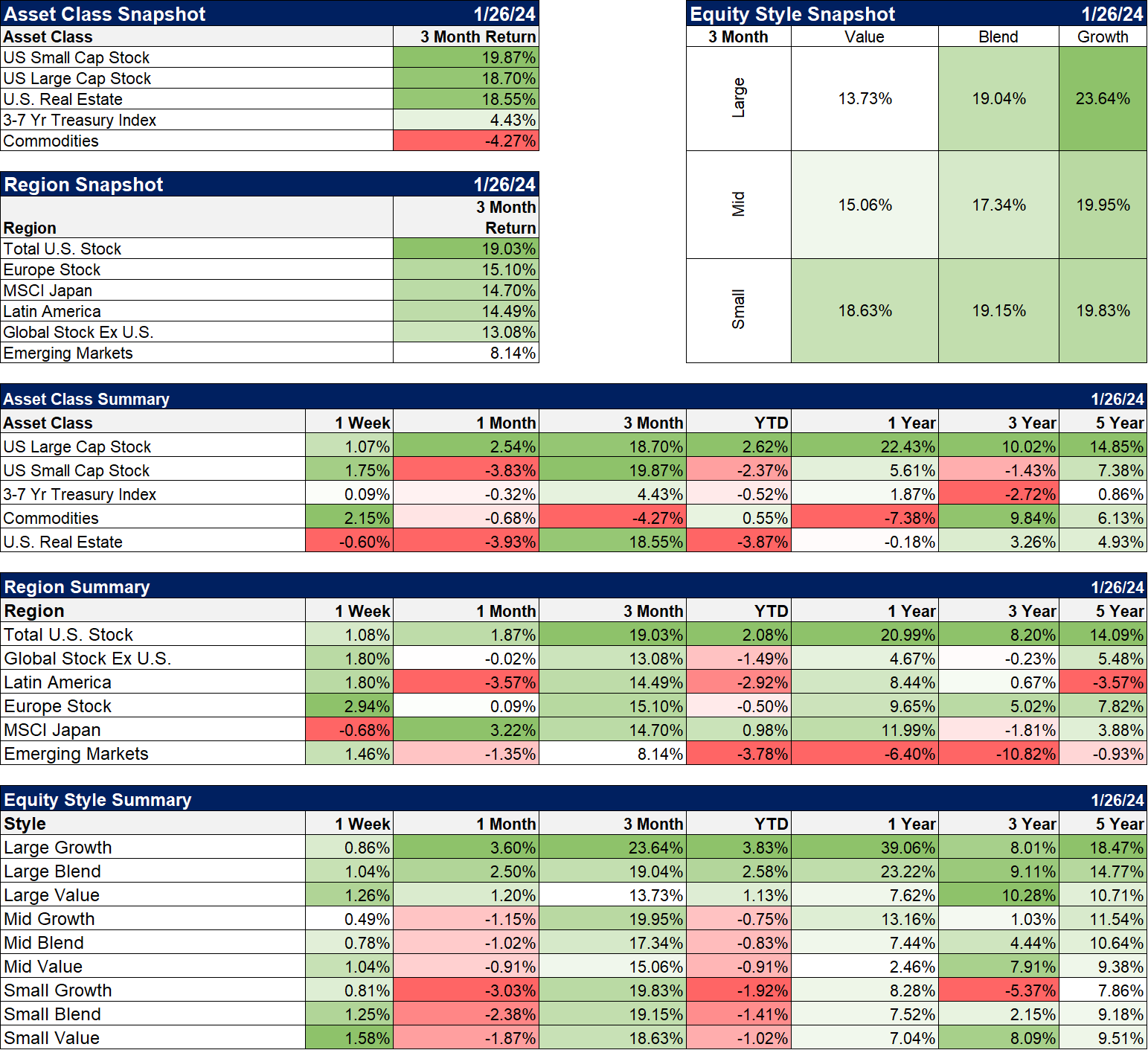

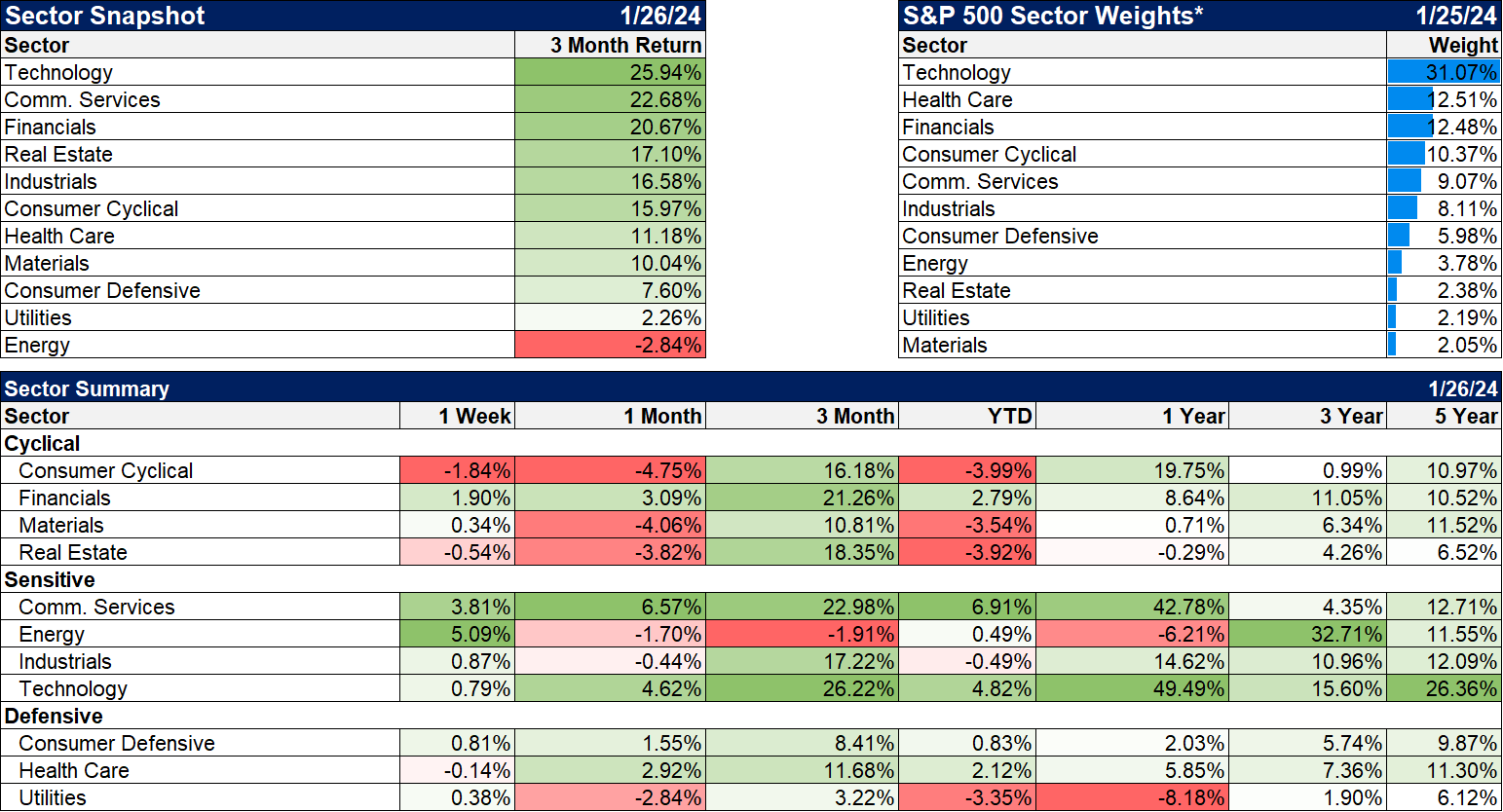

One of the consequences of an economy performing better than expected is that the five rate cuts expected at the beginning of the year are rapidly being priced out of the market. The first rate cut was expected in March with the probability at 74% a month ago. Now the odds are down to less than 50%. Another cut was expected in May with a 72% probability a month ago which is now down to a coin flip. And if the economic data stays as good as it is right now, you’ll see the odds of further rate cuts continue to erode. What would that mean for your investments? If the Fed doesn’t cut rates, the impact on investors will be determined by why. Does the Fed keep rates at these levels because the economy is performing well with trend real growth or better and inflation near their target? Or do they not cut because inflation spikes again? It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out which one of those would be good for investors.

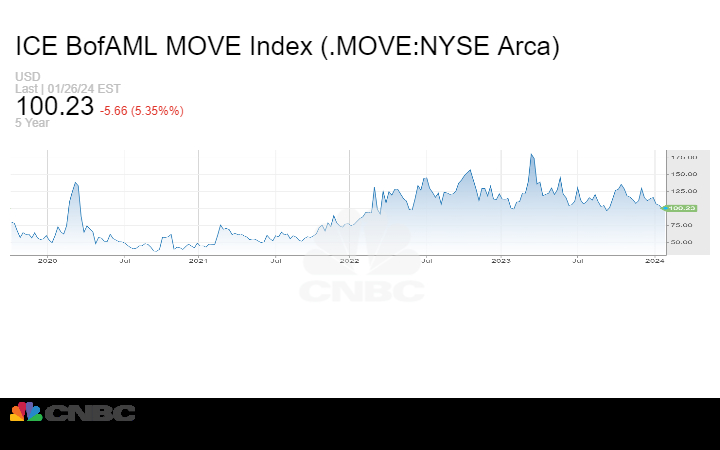

I don’t think we need rate cuts to produce good returns in markets this year and five of them would only happen if we’re in or headed rapidly to recession. Why would anyone root for that scenario? After years of turmoil, I’m rooting for stability, for a Fed that doesn’t dominate the economic news. Bond market volatility peaked last March when it started to become clear the Fed was about done with its rate-hiking campaign. Will it continue? That depends on whether the Fed continues to feel compelled to respond to every twitch of the economy with a change in policy or rhetoric. It is ironic that the Fed introduced “forward guidance” as a way to reduce uncertainty about their future actions but instead produced the opposite, more uncertainty and more volatility.

The economy is functioning as well as it is, not because of the Fed, but in spite of them. The Fed is the problem, not the solution.

Joe Calhoun

Environment

Markets

Sectors

Market Indicators

Stay In Touch