Last week President Trump nominated the head of his Council of Economic Advisors, Stephen Miran, to fill a vacant seat on the board of the Federal Reserve. Miran will fill the seat recently vacated by Adriana Kugler but supposedly only to complete her term, which ends on January 31st, 2026. I say supposedly because I suspect that he’ll be there a lot longer than that.

I’ve written about Mr. Miran before, specifically on his paper, modestly titled A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System, published just after the election, that he claimed had nothing to do with his potential participation in the new Trump administration but read a lot like a job application nonetheless. That paper got a lot of attention and despite his denials, the Trump administration’s approach to trade has largely mirrored that 40 page tome, although the effectiveness of those reforms is still very much up for debate. Now, with his appointment to the Federal Reserve, we get to read another paper of Mr. Miran’s: Reform the Federal Reserve’s Governance To Deliver Better Monetary Outcomes. After reading it, I am left wondering, Better Monetary Outcomes for whom?

The paper, co-authored with Dan Katz, outlines a restructuring of the Federal Reserve system that is at least as radical as the plan he proposed for restructuring global trade. The gist of the paper is that the Fed’s “pure independence is incompatible with a democratic system” and that a restructuring to make it more accountable to a democratic society is necessary. I don’t think the Federal Reserve has ever had “pure independence” although its original design certainly took potential political influence into account. The paper is somewhat confusing on this point in that it decries this supposed complete Fed independence while also acknowledging that “(l)eadership that was traditionally regarded as technocratic has been replaced with highly qualified, but highly political, personnel who move freely between the White House and the Eccles Building.” I guess his appointment to the board does certainly prove that last point.

Mr. Miran and his co-author rightly point out that “(e)xcessive control by elected, political actors (like the president) interferes in good policy and results in bad economic outcomes” but their solution is to shorten the terms of board members and have them serve at the will of the US President. They attempt to balance this expansion of executive power by nationalizing the Reserve Banks, having governors of the states in their districts select their boards and allowing the Reserve Bank leaders to vote at every meeting of the FOMC. They go on, however, to acknowledge that this arrangement would still mean the political party of the executive branch would likely have a majority of the votes on the FOMC and so would be able to exert effective control over monetary policy. Ironically, they also point out that “when the Fed backs one party’s economic proposals, it has the effect of an intervention in electoral politics”. Thanks for clearing that up.

While Miran rightly points out that “to pretend that one can easily shift between highly political and allegedly nonpolitical roles without letting political biases inform policy is, at best, naïve—and, at worst, sinister”, but his solution is to make the non-political roles political. Throughout the paper, he favors political actors over more technocratic appointees saying that his reforms would “increase the incentives for presidents to seek candidates with professional experience in Congress” and “exercising proper oversight…would allow the appointees of any president to discharge their constitutional role faithfully without undemocratic interference from unaccountable professional staff“. He also recommends that “congressional oversight of the Fed should be significantly expanded” while acknowledging that “politicization is a significant problem at the Federal Reserve”. As I said, a tad confusing.

The paper makes some good points about the role of the Federal Reserve. Certainly the Fed in recent years has had a bad case of mission creep and ought to stick to fulfilling its mandates (which ought to be singular by the way) through more traditional central bank tools. But I wonder how putting a lot more politicians into positions of power within the Fed system is going to solve this problem of an already overly political Fed. Getting more politicians involved has never been the solution to any problem.

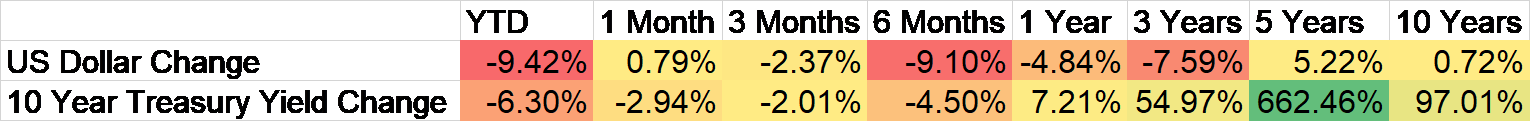

As with his previous paper (actually this one is older, written in 2024), Miran has supreme confidence that he understands the implications of the changes he is proposing. So far, the track record from his paper on trade indicates that confidence might be a tad misplaced. Just as one example, he expected the dollar to rise with the imposition of tariffs and instead the buck is down 10% this year. That isn’t the only thing he’s gotten wrong but even he got everything right in that paper, hubris is a dangerous trait in an economic policy maker. Central planning doesn’t work better if the planners happen to be of your favored political party. One of the things that bothers me the most about the new Trump administration is their penchant for centralized, one size fits all, federal solutions to our country’s perceived problems. Tariffs, for instance, are a great example of a type of policy that can be quite useful when narrowly and properly targeted but a blunderbuss of unintended consequences when applied broadly.

In this paper and the trade paper, Miran tries to guess at the market reaction to his plans.

Given the Fed’s central importance to the U.S. economy and financial markets, implementation of our sweeping reform proposals should be carefully managed so as not to create unnecessary market turbulence. In a worst-case scenario, an abrupt announcement of the intent to pursue the reforms that we suggest could risk an increase in long-term interest rates as the market priced in some probability that increased presidential control over the Board of Governors might lead to the installation of Fed leaders who would deliver easier monetary policy during that president’s term.

Ironically, Miran’s mere appointment to the board of governors risks provoking this exact response. Does anyone doubt that he was appointed to the board specifically to advocate for “easier monetary policy during that president’s term”? The president is supposedly continuing to search for a new chairman to replace Jerome Powell next year but my guess is that the president appointed the new chair last week.

What matters for investors is how the market perceives Miran’s appointment and this paper. He is obviously a dovish vote on the FOMC or he wouldn’t have been appointed. Furthermore, his paper on trade blamed trade deficits on a chronically overvalued dollar – something for which there is scant evidence – and lowering rates would obviously help to alleviate that “problem”. If the market perceives that he is gaining support inside the Fed, we are likely to see his wish of a cheaper dollar fulfilled. Historically, the movements of the dollar, up and down, have had dramatic impacts on asset class returns and economic variables. A falling dollar, a weak dollar is not favorable for the US economy or US markets. In general, a weak dollar environment favors non-US stocks and economies (particularly emerging markets) and real assets like commodities, gold, and real estate. A falling dollar is also the very definition of inflation, a reduction in purchasing power that is revealed as higher prices.

Miran’s appointment last week didn’t really move markets but it was probably the most important news of the week. Miran has identified and highlighted problems with how the Federal Reserve conducts monetary policy and implements bank regulation but his solutions seem unlikely to solve them. In the conclusion of his paper, he advocates gradual implementation of his plan to avoid “unnecessary market turbulence” but I don’t think that would make much difference. Markets are pretty good at discounting the future and will not wait to see the final result; they will adjust to the end product long before it arrives. I would also point out that his preferred path for trade reform was one of the few things in that paper that the president completely ignored. President Trump doesn’t do things slowly and if he decides to implement Miran’s plan it won’t be incremental. The market reaction probably won’t be incremental either.

Environment

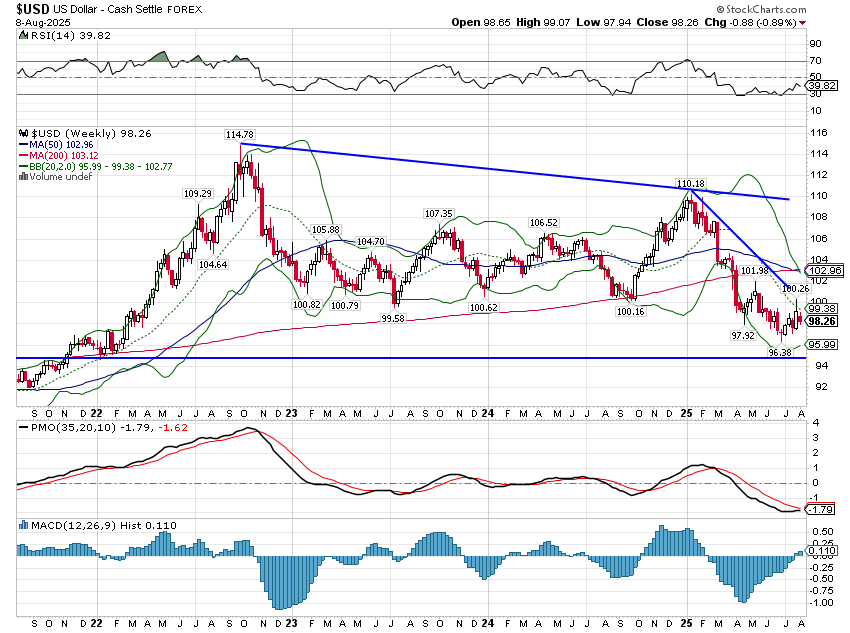

The rally I’ve been looking for may already be over. We had a move above 100 two weeks ago but it lasted about 10 minutes and the buck fell nearly 1% last week. Regardless of the short term movements, I continue to believe the dollar has made a long term top. The impetus for the move lower is the weak dollar policy of the Trump administration. A 20-30% devaluation would likely help to achieve their goal of lowering the trade deficit but probably not in the way they think. A weaker dollar is likely to come with a weaker US economy and that will, along with the higher prices associated with a weaker dollar, reduce imports. A Pyrrhic victory indeed.

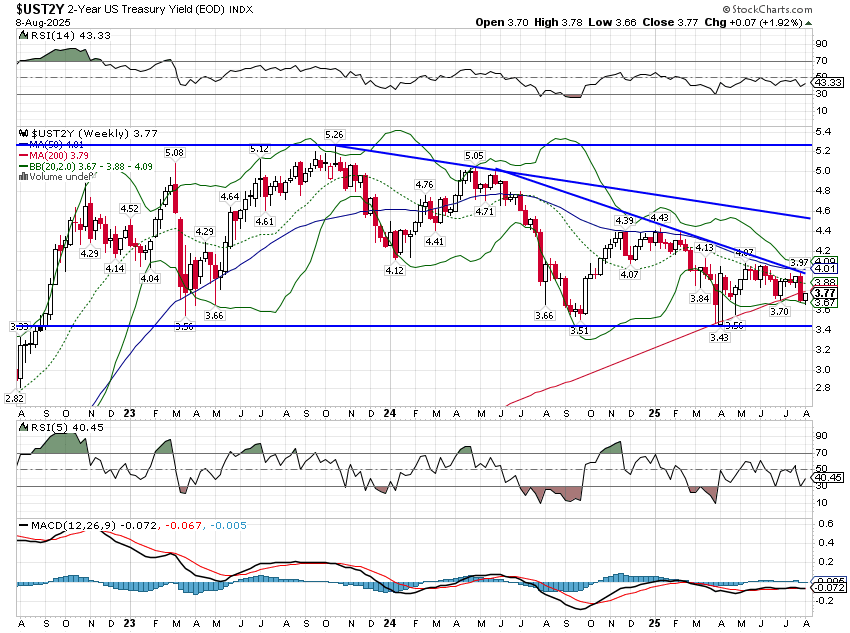

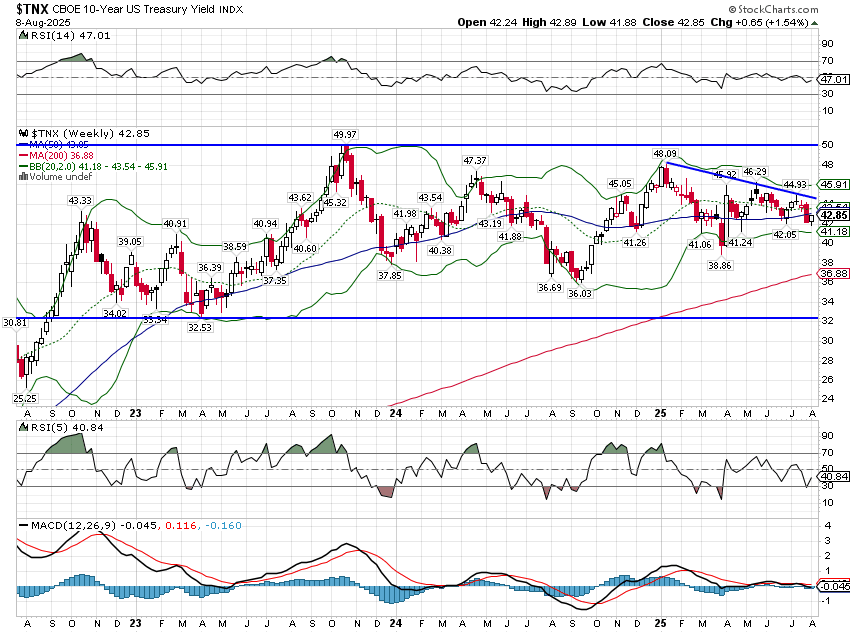

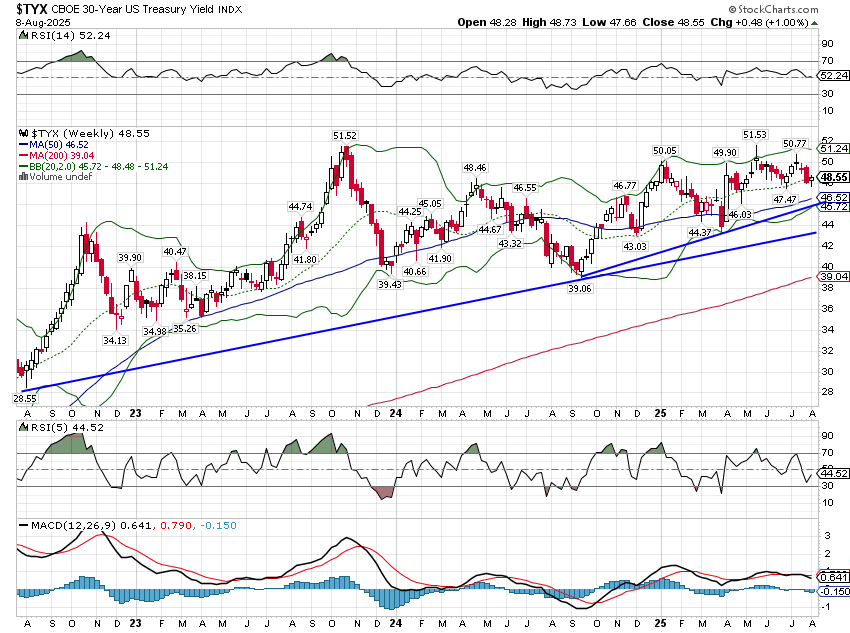

Interest rates were higher last week but only by about 7 basis points. While most people are focused on the Fed and the short end of the curve, the important movements will happen on the long end. The 10-year Treasury yield has been very resilient this year as markets appear to be concerned about the tariff impact on prices. The 30-year Treasury yield is in an even more obvious uptrend.

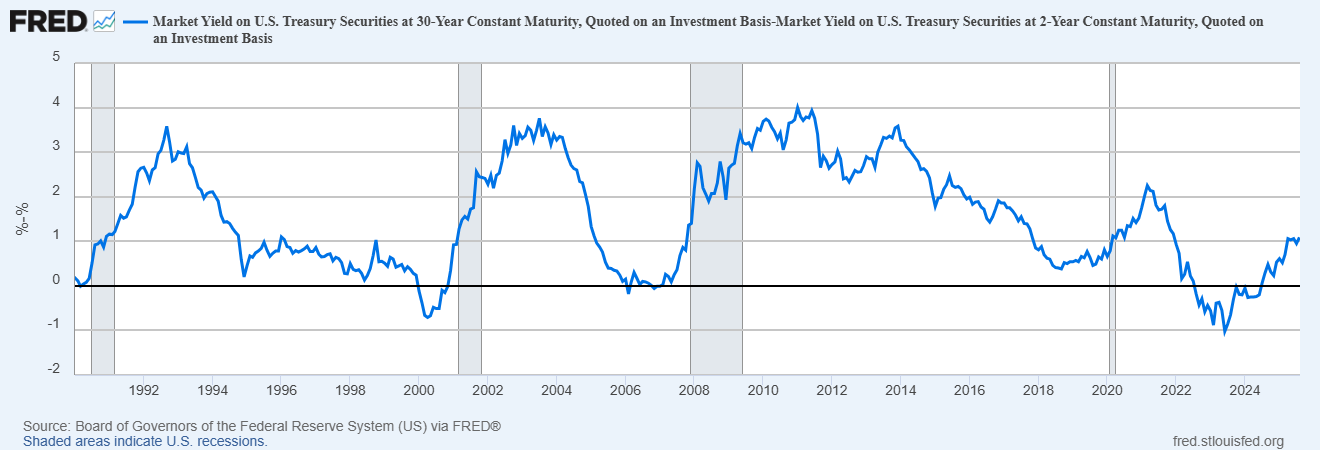

The 30-year/2-year Treasury term spread (yield curve) is steepening much more rapidly than the 10/2 or 10/3-month curves. This is a bear steepener, where long rates are rising faster than short rates, and is usually associated with higher nominal growth expectations. If this steepening continues along with a weaker dollar, that would seem to point to stagflation. I don’t think, however, that a final verdict is in on this. The more traditional expectation would be for weaker growth to lead to lower short and long term rates.

Markets

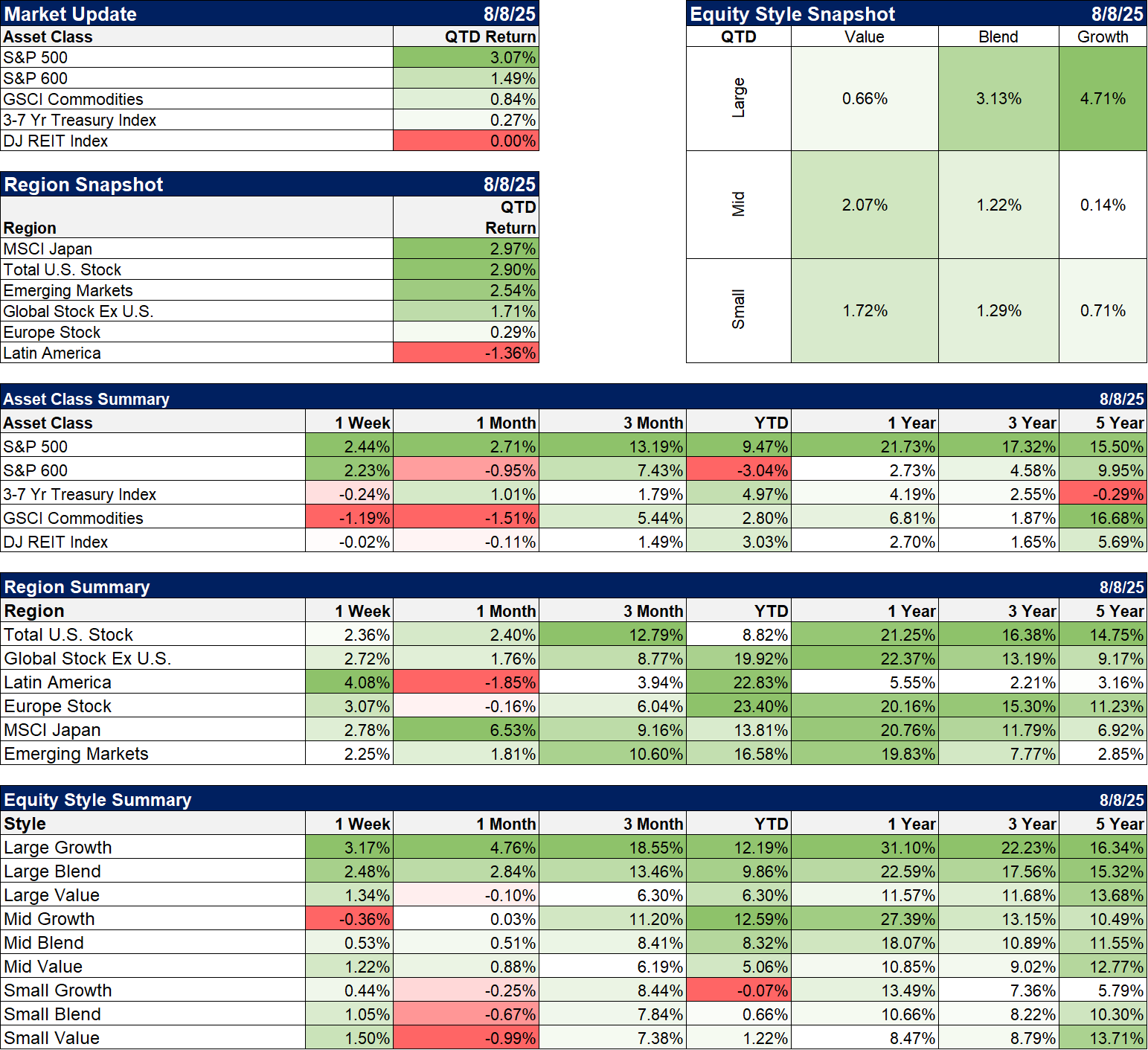

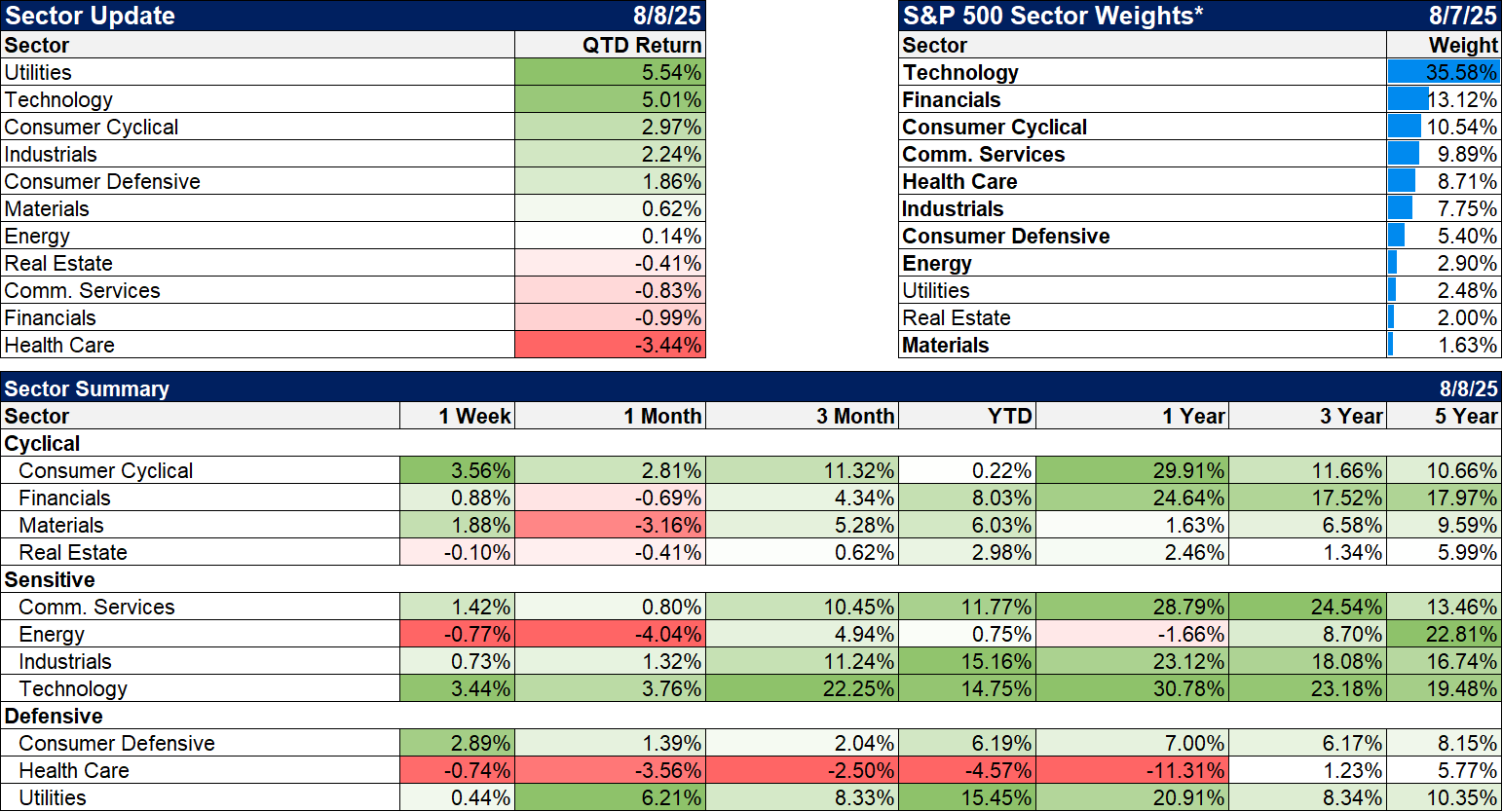

Stocks had a good week but most diversifying assets (commodities, bonds and REITs) were lower. Gold was an exception, up 1% on the week although higher prices reversed some Friday afternoon as the Trump administration tried to clarify whether tariffs on Switzerland applied to the yellow metal. The Trump administration is upset that their actions have created demand for gold from Switzerland and so the bars used at the COMEX, refined in Switzerland, were targeted for a tariff. I have no doubt it was intentional but when the prices spiked the administration claimed an administrative error. A lot of that going around these days.

With a weaker dollar, international stocks once again took the lead with Latin America, despite the spat between the US and Brazil, leading the way up over 4% for the week. The Brazilian Real was up nearly 2% last week and is up nearly 12% against the dollar this year which accounts for roughly half of the Latin American index gains this year (Brazil is nearly 60% of the index).

Sectors

Earnings season has been very upbeat with the emphasis on “beat”. 80% of companies have reported better than expected earnings and revenue growth. Earnings growth for Q2 is, so far, about 12% above Q1 and 10% above the same quarter a year ago. Margins are coming in over 12%, back near all time highs. Estimates for 1-year forward earnings is for growth of about 15%. All of that is much better than expected and explains, to some degree, the rise in the stock market. Of course, we don’t know how much earnings have been affected by the adjustments to tariffs. We know, for instance, that companies – and individuals to a lesser degree – front ran the tariffs in Q1 by accumulating inventory and that they ran down that inventory in Q2. Will the need to restock affect Q3 margins and earnings growth? I don’t know but the expected growth of Q3 earnings versus Q2 is, right now, only about 3.7% although Q3 25 vs Q3 24 is a more robust 13%. We also know that a lot of companies have put off changes due to tariffs – layoffs and price changes – in hopes that the final rates wouldn’t be that bad. With the average tariff now up near 20% that hope looks empty.

One of the biggest surprises this quarter had been in the healthcare sector, with revenue growth of 10.8% only lagging the 15% gain in the technology sector. That growth rate was expected to only be 7.8% at the end of the quarter. What makes this even more surprising is that healthcare is the worst performing sector QTD (meaning essentially earnings reporting season), YTD, 1 year, 3 years and 5 years. Good corporate results and poor stock price action sounds like an opportunity to me.

Economy/Market Indicators

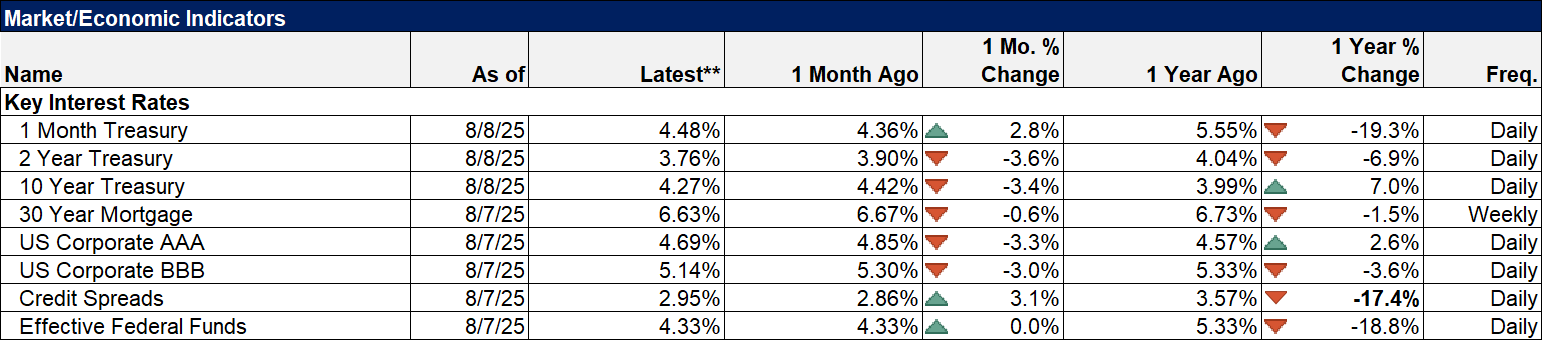

Credit spreads spiked on August 1 by 27 basis points to 3.13% but have since pulled back in to 2.95%. I don’t know if it is significant but it is interesting that spreads were not able to get back down to the lows of the cycle and now appear to be heading higher again. If the economy starts to falter this is where we’ll get the first inkling of a problem. Credit investors tend to be more sensitive to changes in the economic outlook than equity investors. Nothing to worry about yet but this is on our radar.

Economy/Economic Data

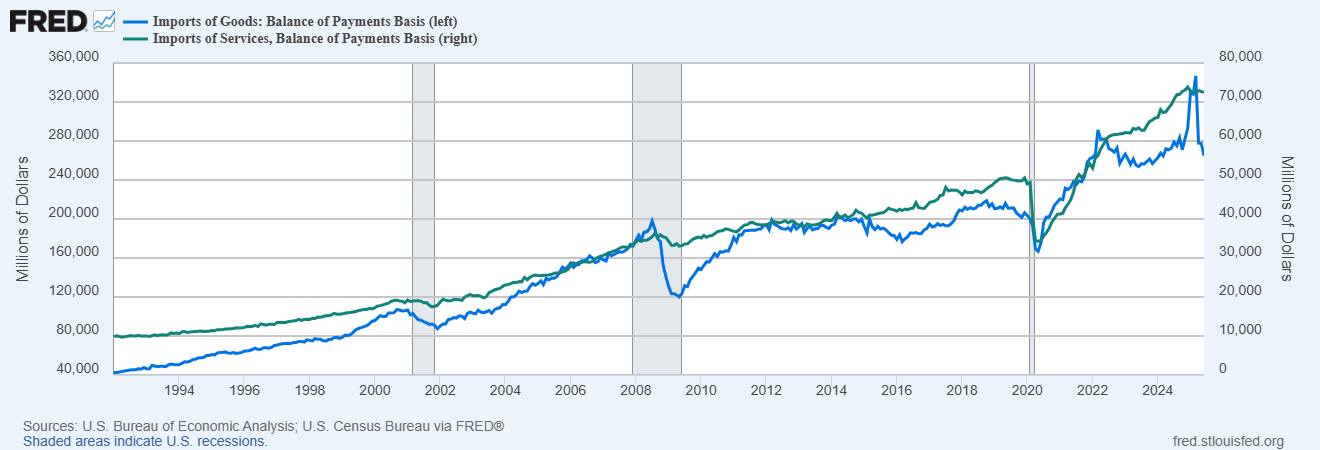

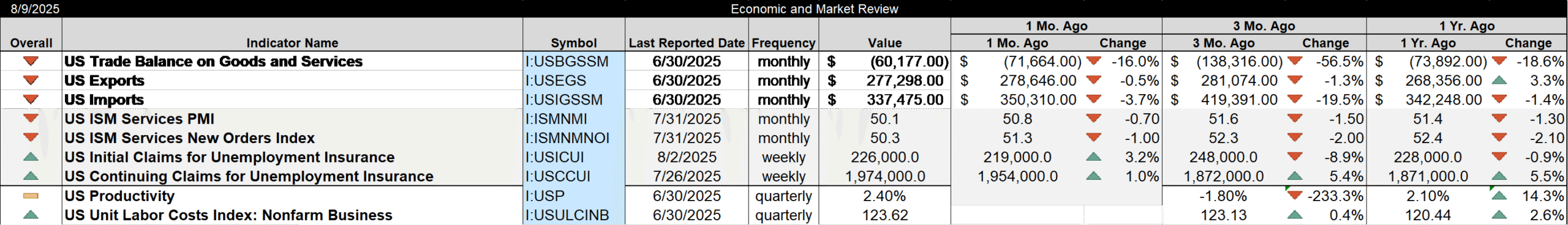

The trade balance improved in June and I’m sure that warms the cockles of the Trump administration’s heart. It doesn’t, however, mean that tariffs are “working”, as I saw so many on X saying this week. Imports have dropped in the second quarter because they spiked starting after the election in anticipation of tariffs. Imports of goods and services are now back to where they were prior to the election. You can see it more starkly in goods imports. Services imports are down some too but not as dramatic as goods. In case you didn’t know, only goods imports are subject to tariffs.

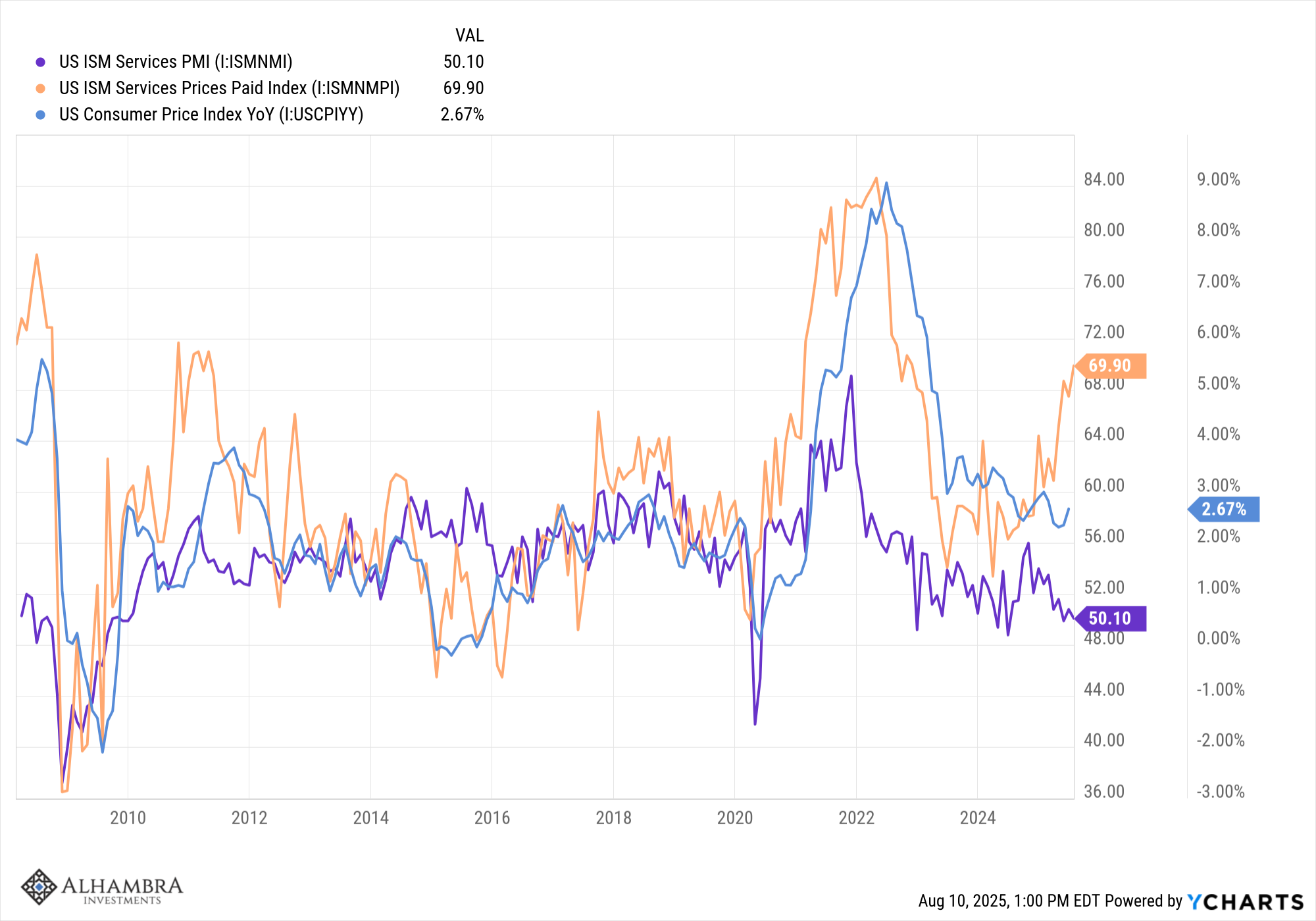

The ISM Services index fell to 50.1 in July, on the cusp of turning into contraction. Readings below 50 are fairly rare although more common in recent years. Until the post-COVID era, all the sub-50 readings were during recession. However, the services index has only been around since 2008 so there isn’t a lot of history that includes recessions. Of more importance is the prices paid index which rose again in July to 69.9, up from 60.4 in January. The ISM prices paid indexes tend to lead the CPI by a couple of months so this might be signaling a spike in prices in coming months.

Stay In Touch