The Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee met last week with both Lisa Cook and Stephen Miran voting (more on that later). The committee lowered the target for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points and hinted at future cuts:

Recent indicators suggest that growth of economic activity moderated in the first half of the year. Job gains have slowed, and the unemployment rate has edged up but remains low. Inflation has moved up and remains somewhat elevated.

The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. Uncertainty about the economic outlook remains elevated. The Committee is attentive to the risks to both sides of its dual mandate and judges that downside risks to employment have risen.

In support of its goals and in light of the shift in the balance of risks, the Committee decided to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/4 percentage point to 4 to 4‑1/4 percent. In considering additional adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

It is striking to me that the Fed decided to cut rates because “downside risks to employment have risen” even as inflation is above their target. The unemployment rate, at 4.3% is well below the long-term average of 5.6% (back to 1948). Core PCE inflation (the Fed’s preferred measure), on the other hand, was up 2.9% year-over-year in July versus 2.6% in April and the Fed’s target of 2%. Obviously we’d like unemployment to stay below the long-term average but are we okay with an inflation rate that is rising over the last quarter from a level that was already higher than the target?

The bigger question is whether the Fed has control over these variables and I’ve always been in the camp that says not nearly as much as most economists or investors believe. The tragedy of Milton Friedman’s maxim that inflation is “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” is that it has been used to relieve politicians of any responsibility for too high inflation or too weak growth, with the Fed always readily available to take the blame.

Inflation is certainly a monetary phenomenon but the value of money is determined by supply and demand and the Fed generally only has control over the supply side of the equation – and “control” is a vast overstatement of their powers. It is all the other monetary policies that affect the demand side and the Fed has to try and respond to changes in those policies in real time with little clarity on their effects. We’re seeing this play out in real time right now with the Fed’s struggle to determine the impact of the massive changes in economic policy by the Trump administration.

In a complex global economy, the impact of a change in US tax, regulatory or trade policy is hard to predict in advance beyond a general outline. All policy changes come with the ceteris paribus disclaimer – all other things being equal – but we know that isn’t what happens in the real world where economic actors – those pesky humans – sometimes do things economists don’t expect. And if the politicians make big changes to all those things, the job of predicting the outcome is, well, impossible.

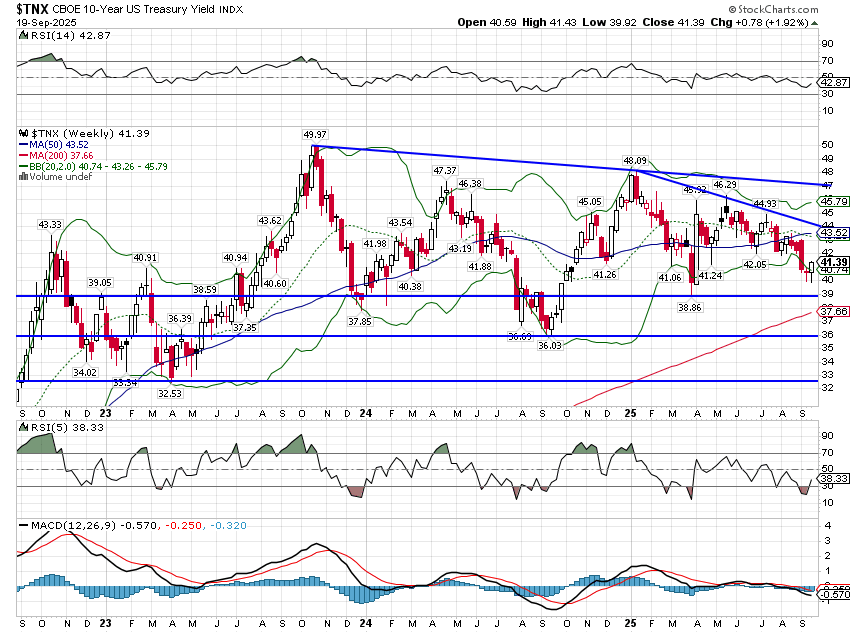

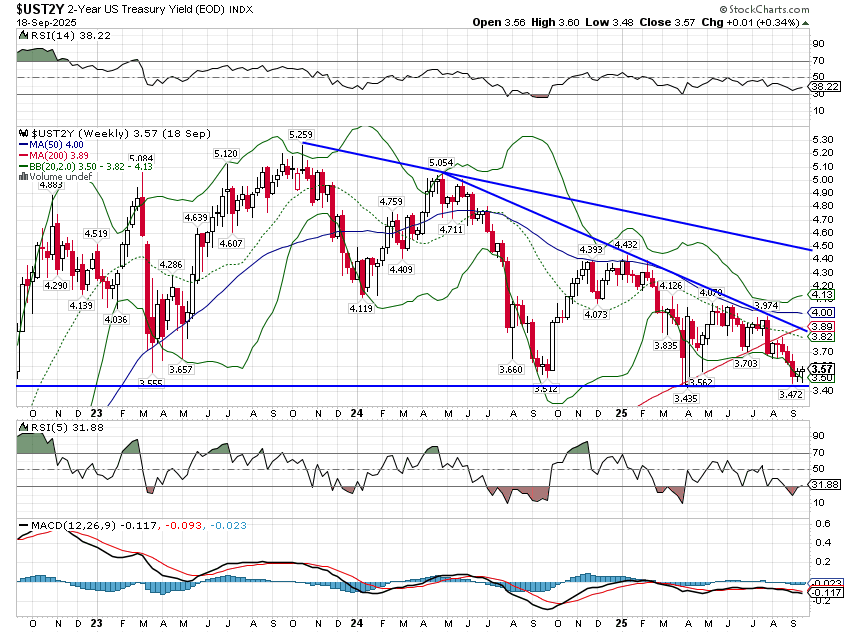

All we can really do as investors is watch the market’s reaction to changes in Fed policy. In this case, the initial market reaction has been mildly positive with both nominal and real interest rates rising some after the change. The 10-year TIPS yield is up 9 basis points and the 10-year Treasury yield 10 since the day before the FOMC decision. It has only been a couple of days and it is a small move, but at least it is in the right direction.

That doesn’t mean the market will be right just that the consensus of investors is that the quarter point cut was sufficient to keep the economy growing in a way that doesn’t make inflation any worse. The market’s assessment will change as further economic data is released, rates rising if growth is better than currently expected and falling if it’s worse. For now, rates are near the bottom of the range they’ve been in for most of the last three years but there’s no cause for alarm.

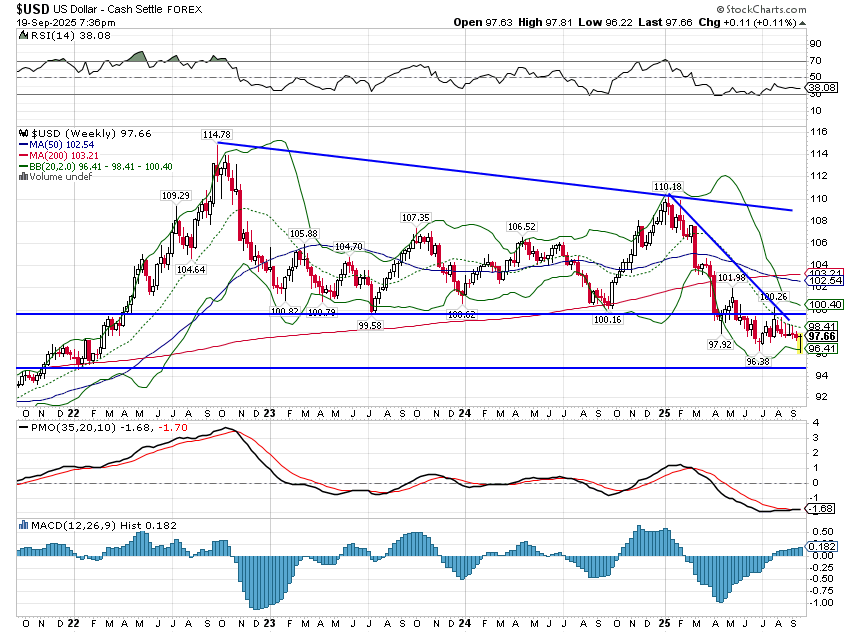

The dollar is also up some since the rate cut but as with interest rates, it is still in a downtrend and just off its lowest close since 2022.

The best we can say about the change in Fed policy is that they didn’t make things worse. Expectations for economic growth and inflation haven’t changed much but neither is where anyone would want them to be. Inflation expectations remain elevated above the Fed target and growth is still below the long-term trend. And the long-term trend of about 2% wasn’t great anyway.

Unfortunately, getting trend growth above 2% isn’t merely a matter of the Fed pulling the right lever. It also isn’t about who is pulling that lever, which brings me to Lisa Cook and Stephen Miran. Governor Cook has been accused by the administration of mortgage fraud and they are now asking the Supreme Court to allow the President to fire her.

I don’t know if she has engaged in mortgage fraud although, based on numerous reports since this first surfaced, it seems that if she has, so have a lot of other prominent people, including the current Treasury Secretary. Mortgage fraud isn’t what this is all about anyway. This President, like many Presidents before him, wants to control interest rates so he can manipulate the markets and the economy to the benefit of him and his party. Careful what you wish for Mr. President; if you succeed, you will have killed a very convenient scapegoat.

As for Mr. Miran, he was the sole dissenter at this FOMC meeting, wanting a 50 basis point cut instead of 25. I was only surprised that he didn’t ask for a full 1% or more since that’s what his boss wants. He is just the latest in a long line of mediocre talents and political hacks appointed to the board so he isn’t special in any way. One might say similar things about Lisa Cook whose academic record is, shall we say, less than impressive.

Investors – and Presidents – put way too much emphasis and faith in the Fed’s interest rate manipulations. The real economy is shaped by many factors and what politicians – and Fed Governors very much fit that description – should do is follow the Hippocratic oath – do no harm. Unfortunately, neither political party seems capable of restraining their worst impulses to meddle. Fortunately, the US economy is resilient and has withstood a lot of bad policy in the past. I expect it will continue to do so now and in the future.

Stay In Touch